Fever in Children Guidelines for Workup

Tamara Cullen, ND

Working with infants and children can be a rewarding yet daunting task. They are so fragile in their first year of life, and then surprisingly they can be remarkably resilient. As an ND, you will be held to the same standards of diagnostic workup as a pediatrician. This is of utmost importance when it comes to fever guidelines, as fever can often be the first and only sign of a challenged immune system.

Keep in mind that there are multiple definitions of fever, but the most standard definition is a rectal temperature of 100.4°F (38.0°C) or higher (about ≥99.7°F orally). All the following guidelines are based on a rectal temperature.

In addition, it is important to remember which populations are considered at high risk for serious bacterial infections, such as meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, bone and joint infection, pyelonephritis, and enteritis. These include the following populations: (1) infants younger than 56 days (because of immaturity of the immune system), (2) older infants (<1 year) who have high fevers (≥102.2°F [≥39.0°C]) and appear ill, and (3) all infants and children who are immunodeficient or have sickle cell disease or underlying chronic liver, renal, pulmonary, or cardiac disease.

For Infants Younger Than 3 Months

In this age group, infections can occur across the placenta, through the birth canal, or after birth. Viral infections are the most frequent, although common bacterial organisms include group B Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes among infants aged 0 to 1 month and group B Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and L monocytogenes among infants aged 1 to 3 months. It is also important to remember that up to 10% of well-appearing infants may have serious infections. In addition, you will often see nonspecific symptoms associated with a fever, such as decreased appetite, irritability, cough, rhinorrhea, vomiting, diarrhea, and apnea. That is why pediatrics is such a challenge!

Hospitalization is required for infants younger than 29 days with a rectal temperature of 100.4°F (38.0°C) or higher. (Some sources say the same for infants younger than 58 days.) They will be given intravenous antibiotics in the hospital for 48 hours until cultures of blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and stool (if diarrhea is present) are all negative. This said, when a parent calls you and her newborn has a temperature denoting a mild fever with no other symptoms, it is OK to first ask if the baby is swaddled or dressed warmly. The parent may unwrap or undress the baby, wait a few minutes, and repeat the temperature measurement, all while you are on the phone. If the fever persists, then you will be sending them to the hospital, with the information that they will receive a full workup there. Most hospitals are very strict on this policy, but they may differ in their requirement of testing based on the age of the infant (<29 days or <58 days).

Hospitalization is required for infants aged 1 to 3 months under the following conditions: (1) toxic appearance (pale or cyanotic, lethargic, or inconsolably irritable, with possible tachypnea, tachycardia, or poor capillary refill) or (2) suspected meningitis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or bone or soft tissue infections that are not responding to oral antibiotic treatment.

Laboratory values can be extremely helpful when there are few signs or symptoms. Criteria for low risk of serious bacterial infection include the following: (1) white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 5000 but less than 15 000/µL, (2) bands of less than 1500 WBCs/µL, (3) normal results of urine analysis with less than 10 WBCs per high-power field, (4) diarrhea with less than 5 WBCs per high-power field, and (5) normal results of cerebrospinal fluid analysis. If there are other concerning signs or symptoms, consider blood cultures, urine culture, chest radiography (if tachypnea or respiratory distress is present), and abdominal radiography.

Low-risk infants in this age range can be treated on an outpatient basis with intramuscular antibiotics until all cultures are negative. High-risk infants in this age range are hospitalized with intravenous antibiotics until all cultures are negative.

For Children Aged 3 to 36 Months

In this age group, the most common organisms include S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and Neisseria meningitidis. Owing to immunization with H influenzae type B vaccine and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 13, rates of these infections are dropping.

All toxic-appearing children with fever need a complete evaluation for sepsis. Intravenous antibiotics and hospitalization are required.

If a child is not toxic appearing and the temperature is 102.2°F (39.0°C) or higher, suggested tests include the following: (1) urine culture for boys younger than 6 months and for girls younger than 2 years; (2) complete blood cell count and blood cultures if the WBC count exceeds 15 000/µL; (3) chest radiograph if respiratory distress, rales, or tachypnea is present; (4) stool culture if blood and mucus are present or more than 5 WBCs per high-power field; and (5) empiric oral antibiotics for children whose WBC counts exceed 15 000/µL, followed by reevaluation in 24 to 48 hours.

If the child is not toxic appearing and the temperature is less than 102.2°F (<39.0°C), no testing is required. The child can be observed at home.

The likelihood of bacteremia rises with increased fever and elevated WBC counts, absolute neutrophil counts, C-reactive protein level, and procalcitonin level. This is the case even without clinical indication of serious infection.

For Children Older Than 3 Years

The most common pathogens in this age group include S pneumoniae and N meningitidis. Children of this age are viewed the same as the adult population with fever and are considered at high risk if their temperature is 104.0°F (40.0°C) or higher, especially if they are toxic appearing.

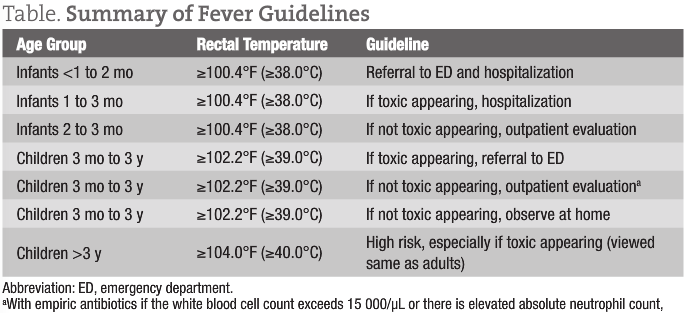

A summary of fever guidelines is given in the Table.

Tamara Cullen, ND is a 1999 graduate of Bastyr University, Kenmore, Washington, and practices primary care medicine in Seattle, Washington. She currently serves as an adjunct faculty member at the Bastyr Center for Natural Health and as a professor of advanced pediatrics at Bastyr University. She is a founding board member of the newly formed Pediatric Association of Naturopathic Physicians. Dr Cullen is coauthor of The Baby Cuisine Cookbook: Internationally Inspired Organic Recipes for Babies from 6 to 18 Months (with Shane Valentine [Seattle, WA: Alina’s Cucina; 2010]. She spends most of her time at her Naturopathic Family Medicine private practice in Seattle. In addition, she loves to swim, run, travel, and spend time with her family.

Tamara Cullen, ND is a 1999 graduate of Bastyr University, Kenmore, Washington, and practices primary care medicine in Seattle, Washington. She currently serves as an adjunct faculty member at the Bastyr Center for Natural Health and as a professor of advanced pediatrics at Bastyr University. She is a founding board member of the newly formed Pediatric Association of Naturopathic Physicians. Dr Cullen is coauthor of The Baby Cuisine Cookbook: Internationally Inspired Organic Recipes for Babies from 6 to 18 Months (with Shane Valentine [Seattle, WA: Alina’s Cucina; 2010]. She spends most of her time at her Naturopathic Family Medicine private practice in Seattle. In addition, she loves to swim, run, travel, and spend time with her family.

Sources

Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al; Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source [published correction appears in Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(9):1490]. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(7):1198-1210.

Hay WW Jr, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, Deterding RR. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

Mazzano S, Bailey B, Gervaix A, Cousineau J, Delvin E, Girodias JB. Markers for bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(5):440-446.

Smitherman HF, Macias CG. Evaluation and management of fever in the neonate and young infant (less than three months of age). UpToDate 19.1. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-management-of-fever-in-the-neonate-and-young-infant-less-than-three-months-of-age. Accessed July 22, 2011.