Last Resort: Ethics, CAM, and Terminal Patient Care

Laura DeVincentis, ND, LAc; E. Feigenbaum, PhD

The reality of dying is an existential truth that persons often would rather not consider including medical professionals. As an ethicist working with a naturopathic doctor, we were moved by Dr. Heidi Kussman-Armstrong’s consideration of end of life care in “Tumor Mass vs. Spirit.” Here, we explore the ethical obligations and dilemmas for naturopathic doctors and hope this will contribute to future dialogues on professional ethics.[1]

The case was that of a 45-year-old man with stage 4 gastric mucinous carcinomas who sought naturopathic care to address palliative and quality of life concerns. Despite a steady decline, the patient decided to continue with naturopathic care, even as the tumor grew and symptoms worsened. While he outlived the anticipated lifespan and believed his quality of life had improved owing to naturopathic care, Dr. Kussman-Armstrong indicates that naturopathic treatments would no longer be beneficial. Still, the patient opted to continue treatment with spirit and faith in the human body’s healing ability and a belief that naturopathic care improved his quality of life.

This case examines the relationship between patient and doctor and examines the ethical principles that dwell at the crossing of medical decisions, prognosis, and dying. In identifying and clarifying the ethical issues in this case, we hope to address these concepts as they apply to end of life care.

Ethical Dilemma

We explore the ethical dilemma of a patient’s use of complementary and alternative medicine as a continuing part of terminal patient care. We ask: “What does it mean, morally, when a patient seeks care that will not cure?” We applaud Kussman-Armstrong’s consideration to support her patient’s decisions, even when they varied from her view. While standard approaches were unacceptable to the patient (like rejection of chemotherapy), the dilemma centered more on the patient’s interest in pursuing naturopathic approaches, even as death became a certainty. It may be an uncomfortable situation for the naturopathic doctor (being turned to as a last resort), particularly if the outlook is bleak through alternative care. Giving any patient disappointing news is fraught with tension for anyone whose professional duties include a commitment to helping people.

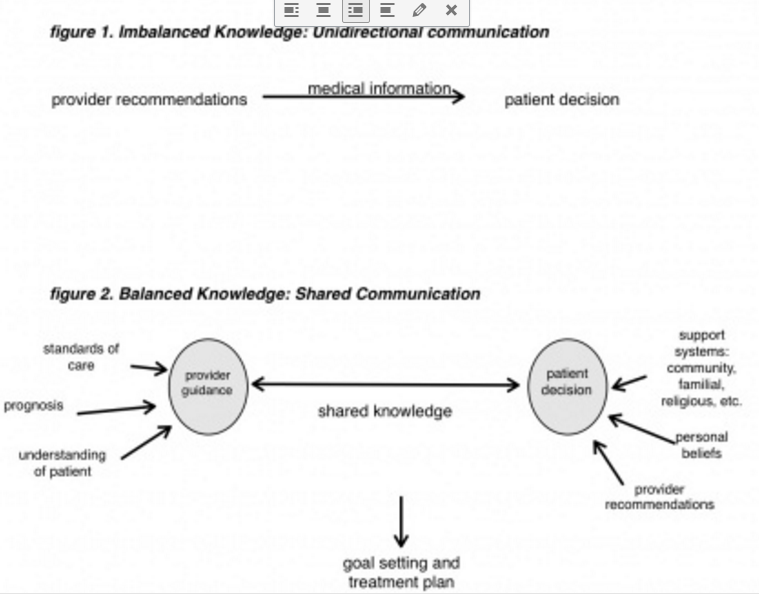

One aspect of evaluating the ethical dilemma begins by considering the perceptual differences between the respective knowledge bases of the providers and the patients. Comparing medically justifiable, scientifically sound, and evidence-based knowledge to the patient or lay person; understanding of treatments; and relevant issues may seem overly paternalistic by favoring the “scientific” over the “personal.” Although it is becoming more frequent for conventional physicians to integrate a whole-person approach to health care, naturopathic care adopts a genuinely holistic concern and openly acknowledges the value of mental, spiritual, emotional, and physical wellness. This depth of communication increases the likelihood for deepened patient-physician trust. Yet even in the best provider-patient relationships, a power difference may emerge resulting from the patient’s trust in medical knowledge (see Figure 1), and this may lead to an imbalanced relationship in which the providers have undo influence. This power differential is enhanced by the vulnerability of patients facing terminal illness, and it requires additional sensitivity and awareness by the provider to maintain equality of the relationship.

Kussman-Armstrong’s case analysis promotes an equitable relationship, in part by acknowledging that patient beliefs serve as the foundation of the patient-provider relationship (Figure 2). In a relationship, party A seeks out B for its expertise, and thus, party A remains dependent upon party B for direction and care. Instead, Kussman-Armstrong describes a scenario in which parties A and B work together to respond to a problem, solving it through shared information and goal-setting. This balanced approach changes the dynamic of the relationship so it can be easily accepted, if medical knowledge (patient benefit) is taken as more significant than the patient’s beliefs (patient autonomy).

Moral Principles

The core moral principles at play in the provider’s recommendations for end-of-life care involve benefiting the patient’s welfare and interests, nonmaleficence, preventing harm to the patient, and allowing patient autonomy (which prioritizes an individual’s right to self-determination as facilitated by the shared knowledge approach to communication) (Figure 2). Beneficence, which seems obvious to patients, may be conflated by a physician’s broader understanding of terminal conditions when the provider wonders if treatments are doing any good against the options of the end stages of a terminal illness. Nonmaleficence requires providers to consider all prospective harms. For instance, providers may need to weigh carefully the nuances of care, such as considering if/when the treatments become physical harms. Or considered emotionally, providers may need to address how to deliver truths about end-stages of illness, and yet refrain from giving false hope, when they contradict a patient’s beliefs or hopes. Communication with patients sometimes includes delivery of deeply difficult concepts and prospects, and if delivered harshly, may result in direct harm to the patient. No matter how realistic, gently conveyed and supportive truth-telling is more-valuable than merely delivering cold truths. Similarly, false hopes may be as harmful as they are untrue to the patient and his/her friends and family.

As Dr. Kussman-Armstrong states, there was a point when the goals of care were not being met: The tumor persisted and weight loss continued. Yet, the patient perceived benefits of care for his quality of life. The patient valued the continued care as it changed, and the provider’s gentle delivery of truth effectively supported his autonomy. Dr. Kussman-Armstrong rightly acknowledges that “healing does not always occur on a physical level and in terminal disease, physical healing may be inappropriate to focus upon solely.”[1] Belief is the precursor to action, and physicians play a key role in informing beliefs to patients about their illnesses. To maintain an ethically guided practice, provider communications must strike a delicate truth, capable of being both honest and gentle, to equip patients with knowledge while respecting their beliefs and decisions.

Laura DeVincentis, ND, LAc, completed her studies in 2001 at NCNM in Portland, and joined Preventive Medicine Group in Ohio after graduation. Since 2005, Dr. DeVincentis has served as medical director of CAM PPO of America, a credentialed network of CAM providers serving an estimated more than 50,000 members nationally.

Laura DeVincentis, ND, LAc, completed her studies in 2001 at NCNM in Portland, and joined Preventive Medicine Group in Ohio after graduation. Since 2005, Dr. DeVincentis has served as medical director of CAM PPO of America, a credentialed network of CAM providers serving an estimated more than 50,000 members nationally.

E. Feigenbaum, PhD, completed a graduate certificate of advanced studies in bioethics and went on to complete a doctoral program focused on applied ethics in 2004. A former college instructor, Dr. Feigenbaum now serves as director of ethics and research at CAM PPO of America.

Reference

- Kussman-Armstrong. Tumor vs Spirit: Body and mind. Naturopathic Doctor News & Review. 2010:6.