A Combined Approach to Acne Success: Beyond Systemic/Dietary Change Using Mesotherapy & In-Office Procedures

Michael Rahman, BSc, ND

In clinical practice, acne vulgaris may be one of the most common forms of skin problems. Acne represents a chronic, inflammatory dermatosis affecting the hair follicle.1 It usually manifests as comedones (pimples), which may be open, closed, or progress to inflammatory pustules.

Although more common in males, typically at the onset of puberty, acne is also fairly common in female patients experiencing hormonal shifts, either at puberty or perimenopause. Clinically, an acneic condition may be exacerbated by several factors: drugs, such as oral contraceptives or corticosteroids; systemic or dietary factors including excessive consumption of simple carbohydrates, vitamin or mineral deficiency, or other dietary intolerances; occupational hazards such as chlorinated hydrocarbons; and occlusive environments such as humid or tropical climates. Due to familial tendencies, it is also arguable that there may be genetic predisposition.1

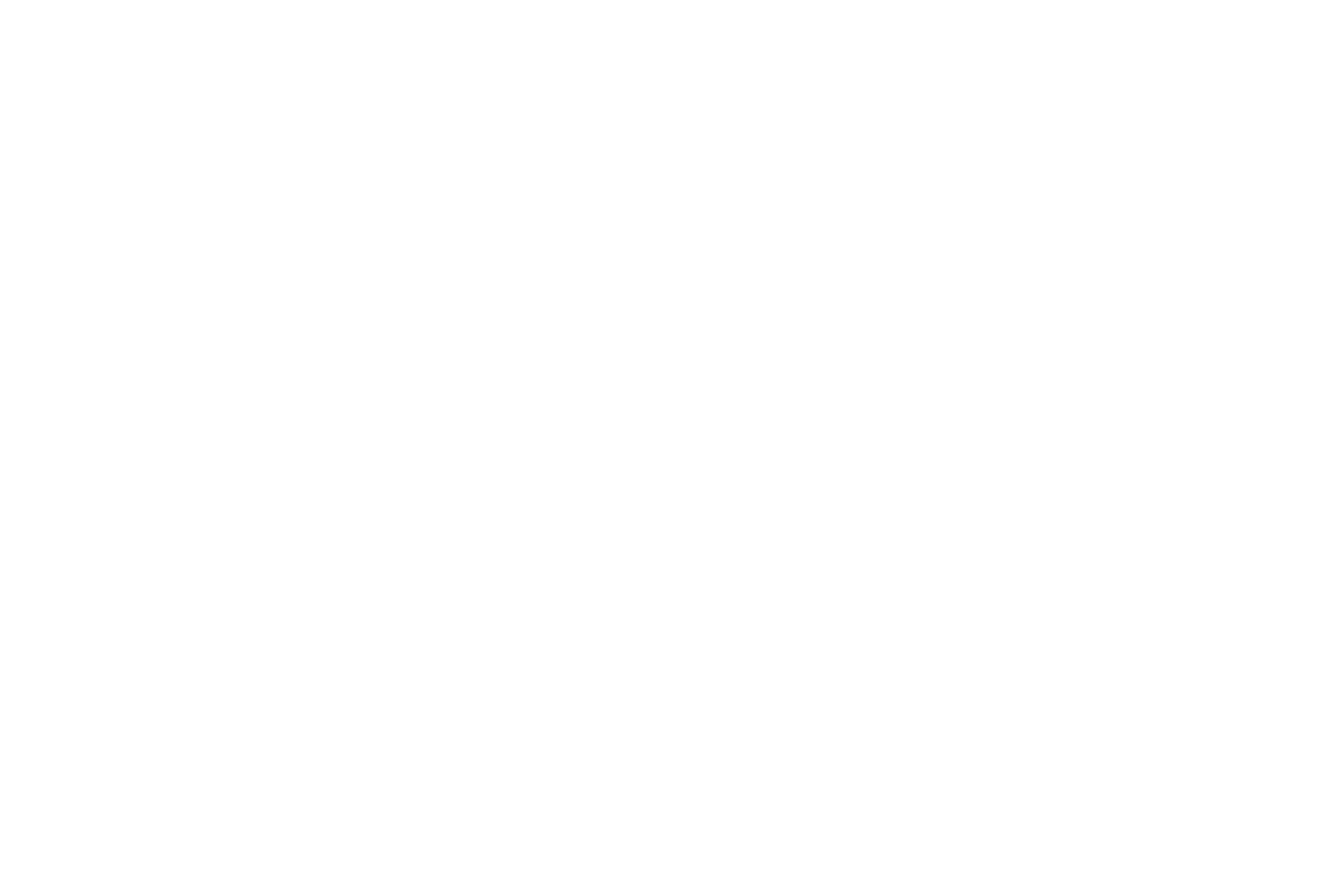

Pathophysiology of Acne

From the perspective of homotoxicology, or accumulation of toxins within the system, acne vulgaris is thought to be due to congestion and accumulation of toxicity within the hair follicle that is either generated from overactivity of the sebaceous gland or from accumulation of bacterial toxicity.

The follicular eruption in acne vulgaris begins with an impaction within the sebaceous follicle to form a comedo. The rupture of comedones leads to an inflammatory cascade and clinically presents as papules, pustules, and nodules. These morphological expressions are highly variable.

Microscopic changes result in hyperkeratosis of the follicles, which leads to blockages in the sebaceous glands and the consequent formation of a closed comodo composed of sebum, keratin, and microorganisms. Most of the microbes are normal skin species, such as non-pathogenic Staphylococcus. It is also postulated that the species Propionibacterium acnes causes a breakdown of the sebaceous oils, liberating irritating fatty acids and causing the inflammatory cascade.2,3 (See Table 1 for more detail.)

Clinical Patterns

Acne patients are oftentimes difficult to manage, as they require a multifaceted approach. As a foundation, it is important to begin with the proper assessment and diagnosis of the patient’s acne condition. Acne is a polymorphic disease that occurs in the face, back, and chest. Acne vulgaris is the most common type. The lesions of acne vulgaris are divided into 3 distinct types:

- Non-inflamed lesions (due to hyperkeratinization)

- Microcomedones

- Closed comedones (white heads)

- Open comedones (black heads)

- Inflamed lesions

- Papules

- Pustules

- Nodules

- Cysts

- Hyperpigmented macular lesions: Usually these are post-inflammatory in nature and seen in the richer, pigmented skin types

Scarring

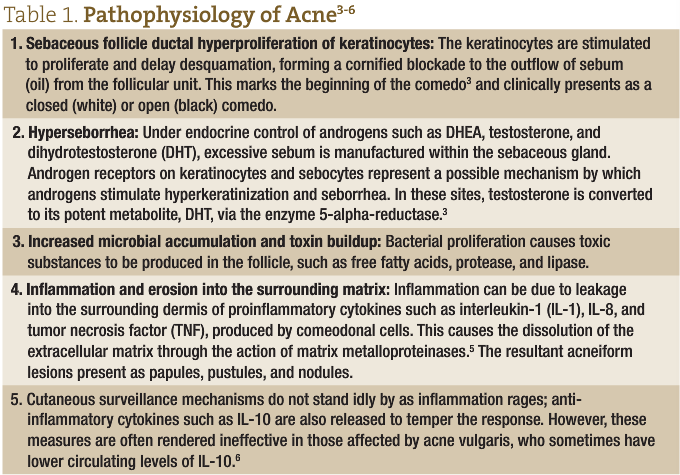

Acne scars can be divided into 4 basic types (Figure 1):

- Atrophic scars: Shaped like an icepick, these scars are narrow (<2 mm), deep, sharply marginated epithelial tracts that extend vertically into the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue

- Boxcar scars: Round, oval depressions with sharply demarcated vertical edges, like varicella scars; they can be shallow (0.1-0.5 mm) or deep (>0.5 mm)

- Rolling scars: Usually wider than 4-5 mm, as a result of abnormal fibrous anchoring of the dermis to the superficial tissue; this produces a rolling or undulating appearance in the overlying skin

- Hypertrophic scars: Keloid in nature

Dietary/Nutritional Treatments

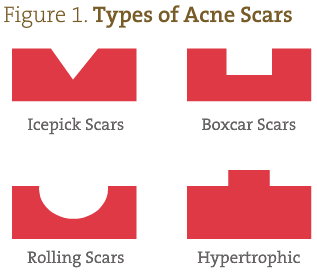

Standard allopathic treatments for acne (systemic and topical) are listed in Table 2.

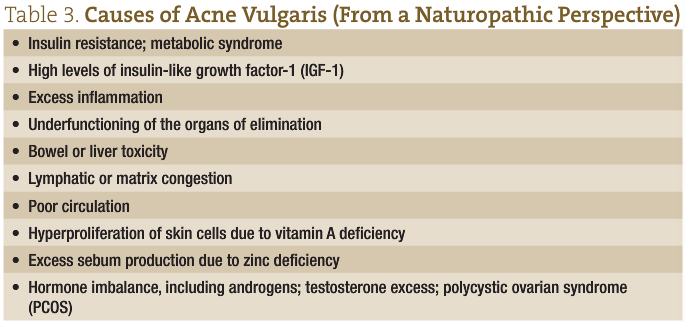

From a naturopathic perspective, the internal protocol for managing acne varies from individual to individual, but some basic tenets remain the same. Firstly, it is important to address any possible underlying dietary insufficiencies. Secondly, or potentially initially, especially in the nodular, cystic forms, hormonal imbalances must be corrected. From a naturopathic perspective, there are multiple possible etiologies of acne vulgaris (see Table 3). A thorough assessment of the patient helps to ensure proper identification of the underlying causes and a more successful outcome.

Diet and Acne

Diet, though not a direct cause of acne, does have an indirect effect on the condition.

The western diet is high in calories, and large portions of these are derived from high-glycemic index (GI) foods. High-GI foods raise blood sugar, which leads to increases in both insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).7 Sheperd surmises that the excess insulin can co-stimulate IGF-1 receptors (IGF1 R).8 IGF1 R can provoke insulin-like effects and also have direct effects on the sebaceous gland, causing abnormal keratinization and increased sebum production.

Hyperinsulinemia also enhances hepatic secretion of IGF-1 and reduces IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3), which increases concentrations of free IGF-1. Circulating IGF-1 stimulates androgen synthesis, 5-alpha-reductase (which converts testosterone to DHT), androgen receptor signal transduction, proliferation of sebocytes, and lipid production.7 IGF-1 and insulin both amplify growth hormone’s stimulatory effect on sebocytes.9 Reducing intake of high-GI foods can help reduce the increased IGF-1 signaling.7

Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) normally binds androgens, thereby preventing them from entering cells to act. Because insulin reduces the amount of available SHBG, increased amounts of androgens are available to act inside the sebaceous glands. The result of these changes is more oil production and enlargement of the oil glands. Of course, this represents only 1 factor in the pathophysiology of acne.

Other naturopathic dietary strategies that have been effectively shown to have an influence on acne include addressing food intolerances (especially dairy),10 anti-inflammatory dietary approaches, and diets based on body morphology.11 My attempt here is to provide a foundational strategy that can be added to, based on the clinical presentation of the patient.

Niacin

The combination of niacin and zinc is being researched in clinical studies for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases such as acne vulgaris. The basis for these investigations is the variety of potential mechanisms of action of these nutrients, including anti-inflammatory effects (inhibition of white blood cell chemotaxis, the release of lysosomal enzymes, transformation of lymphocytes, and mast cell degranulation), bacteriostatic effects against Propionibacterium acnes, inhibition of vasoactive amines, and reduced production of sebum.12 Niacin and zinc may also suppress vascular permeability and the accumulation of inflammatory cells, and protect against DNA damage.12 This vitamin therapy should comprise an intake of 100 mg niacin TID. Niacin is contraindicated in acne rosacea unless a non-flush form is used.

Zinc

Studies have shown that acne sufferers have lower-than-normal levels of zinc in their bodies.13 In one study, the effects of 135 mg of oral zinc sulfate, alone and in combination with vitamin A (300 000 IU) daily on acne lesions were compared with those of vitamin A alone, or placebo.14 After 4 weeks, the number of pustules, papules, and infiltrates in the zinc-treated groups had significantly decreased. The effect of zinc plus vitamin A was not superior to zinc by itself. The mean acne score after 12 weeks of treatment had decreased from 100% to 15%.

To our knowledge, the mechanism for the effect of zinc therapy in acne is not presently known. However, zinc is a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, hence prevents the conversion of testosterone to DHT, which would tend to lower sebum production. Zinc also improves insulin sensitivity.

Vitamin A

Topical retinol A has long been used to treat acne. A retrospective, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled, photographic assessment study assessed the efficacy of topical retinoids as monotherapy in inflammatory acne.15 In this study, pre- and post-treatment photographs were compared of patients with inflammatory acne who received, in double-blind fashion over 12- or 15 weeks, monotherapy treatments of tazarotene 0.1% gel, adapalene 0.1% gel, tretinoin 0.1% microsponge, tretinoin 0.025% gel, or tazarotene 0.1% cream. All 4 retinoids produced clinically significant improvement in the patients.15

However, unlike the long-lasting benefits of the synthetic prescription version of vitamin A (isotretinoin), acne typically returns several months after topical vitamin A is discontinued. Isotretinoin is usually very effective for severe acne, as well as moderate acne refractory to other treatments; improvement is typically seen after 1-2 months of use. A number of adverse effects may occur, including dry skin, nose bleeds, muscle pains, increased liver enzymes, and increased lipid levels in the blood. If used during pregnancy there is a high risk of abnormalities in the baby; thus, women of child-bearing age are required to use effective birth control during treatment with vitamin A.16

External Strategies

Figure 2. Extraction Tool

With the use of an appropriate tool (Figure 2), comedo extraction may help those with comedones that do not improve with standard treatment, at least temporarily.18 Appropriate measures must be made to ensure proper extraction and to stop the cycle of over-accumulation of sebum at the surface of the skin. This can be accomplished by in-office steam extraction and the use of home care products, including astringent type masks (to be used once a week); dermatological soap for adequate cleansing; and, because oily skin is usually a common finding, products such as oil-balancing moisturizers for morning and night, and concomitant use of peeling creams at night. These measures help patients manage their complexion between office visits.

Aside from in-office, basic extraction treatments, treatment strategies may include technologies such as the use of intense pulsed light, microdermabrasion, and chemical peeling.

Intense Pulsed Light

The blue light in Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) is considered antipyogenic. It works by reducing concentrations of P acnes by targeting their endogenous porphyrins. When the lasers excite the porphyrins, they damage the bacterial wall, effectively killing the bacteria. The consensus among researchers, however, is that results are temporary, since colonies of acne bacteria tend to grow back quickly. Results are also incomplete, meaning that lasers alone usually do not completely clear acne. The studies show anywhere from 37% to 83% clearance.19-21

A systematic review of the 19 available controlled studies on lasers and acne, published in The Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, concluded: “… most of the studies were of suboptimal methodological quality… We conclude that optical treatments with lasers… possess the potential to improve inflammatory acne on a short-term basis… Optical treatments for acne today are not included among first-line treatments.”22

Microdermabrasion

Figure 3. Effect of Multiple Microdermabrasion Sessions (Dermal Infusion)

Courtesy of Clarion Medical and Silk Peelâ

A form of mechanical peeling like cryotherapy, microdermabrasion essentially creates abrasion at very superficial levels of the epidermis using fine particulate matter like sand or diamond-tipped heads. In fact, it allows for the sloughing-off of the stratum corneum to provide a more even dermal appearance; it helps stimulate fibroblasts, achieves sebaceous gland rebalancing, and provides a deep cleansing technique (see Figure 3).2 Irregular scars can be improved with dermabrasion, which helps to equalize the margins and eliminate elevations in hypertrophic scarring; once the dermis has been thinned, it never regains its original thickness, and becomes considerably smoother and more even-toned.

Steam extractions usually follow and may be included in the facial treatments, which may also involve the use of clay or astringent type masks. The goal is to allow for the extraction at the site of the follicular unit, including the extraction of the sebum and keratin that accumulates, creating the appearance of the comedones.

Chemical Peels

Chemical peels are usually used as an adjunctive to the basic systemic treatment of acne vulgaris. They are especially useful in addressing a number of the etiological factors. By definition, a chemical peel is the controlled irritation of the skin by chemical means. A caustic agent is applied to burn/disrupt the epidermis and dermis,2 which helps to stimulate rebuilding of the skin. With healing after the peel, the skin becomes firmer, smoother, and more resilient, with even pore size reduction.

In the acneic condition, chemical peels are used to aid in pigmented changes, superficial and medium-to-deep scarring, and control of the keratosis and overactivity of sebum.

There are a number of peeling agents available to us for use; in my opinion, the safest and most suitable for our discussion in a naturopathic practice is the glycolic acid peel. There is also considerable evidence to suggest that azelaic acid is effective for mild-to-moderate acne when applied topically at a 20% concentration.23

Glycolic Acid

Glycolic acid is an alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA) and is in the same category as salicylic acid. AHA is a naturally-occurring carboxylic acid – a natural constituent of sugar cane juice and lactic acid found in sour milk and tomato juice. It has been shown to be keratolytic, and can stimulate the germinative layer and fibroblasts. The effect of glycolic acid is also anti-inflammatory and antioxidative. It acts by thinning the stratum corneum, promotes the breakdown of the epidermis, disperses the basal melanin layer, and allows for production of dermal hyaluronic acid and collagen.2 The formulas available from compounding pharmacies or cosmetic supply include 10, 20, 35, and 70% glycolic acid.

The effect of glycolic acid is time- and pH-dependent. The pH of 70% is partially neutralized so as to achieve a pH above 2; using a solution lower than a pH of 2 could produce tissue damage and necrosis.2

Glycolic acid is most helpful in managing the mild-to-moderate inflammatory cases. On its own, glycolic acid chemical peels are somewhat limited in the treatment of deeper atrophic acne scars.

Technique for using glycolic acid17:

- Cleanse the skin with alcohol to reduce acid neutralization by sebum

- Apply glycolic acid over the entire face within 20 seconds, using a cotton applicator

- A starting application time for weekly or monthly applications is within the range of 3 minutes for 50-70%, and up to 5 minutes for lower concentrations. This can be built up over time.

- Neutralize with sodium bicarbonate solutions or cold water; there is no advantage to using bicarbonate; however, water rinsing must be thorough.

Post-care: Patients must avoid direct sun and be observed for complications such as hyperpigmentation or increased infection. Patients should moisturize frequently. Most of any of these untoward effects are temporary and not usually significant.17

Precautions: Patients usually feel only a slight stinging when the glycolic acid solution is applied. Because only minimal discomfort is experienced, usually no anesthetic is needed. Care is taken to avoid areas too close to eyes and ears. Patients prone to herpes simplex outbreaks may be more vulnerable to activation and outbreak.

Contraindications: Glycolic acid peels should be avoided in patients who have contact dermatitis, are pregnant, or have glycolate hypersensitivity (unless patch testing beforehand shows tolerance).

Mesotherapy

Developed in 1952 by Dr Michael Pistor, MD, mesotherapy is a dermal injection technique that aids in delivery of the medication into the epidermis and dermis to provide a very local effect of stimulating the connective tissue in order to promote healing.24

In Europe, corticosteroids are used for both cosmetic and pain management. The injection of corticosteroids into an inflamed acne comedo is a procedure with high patient satisfaction for immediate relief.25 In this author’s opinion, however, this seems counter-intuitive. The cocktails utilized in my practice are physiologically diluted and prepared specifically to work with the skin and its ability to repair and regenerate. They influence hormonal and receptor-based imbalances, and can specifically be antibacterial and can increase the lymphatic drainage and the circulation to the skin of the face.

Usually only 2 to 3 cc of a pre-manufactured acne formula is injected at any 1 session, but I may also use other commercially prepared remedies specifically related to managing the inflammatory reaction and hormonal imbalances conjunction.

Mesotherapy Techniques:

- “Surround the dragon” or point-to-point techniques require injections in the dermis or subdermis, 3-12 mm (up to 1/2 inch deep)

- Nappage is a technique used to cover large areas. Injections are spaced approximately 2 mm apart and are conducted in quick succession.

The Use of Masks During Facial Treatments

The use of a pre-facial mask such as a peeling mask (left on for about 20 minutes) can also be mixed with numbing cream for effective pain management. If, however, one has done a peeling session, either physical or chemical, I would recommend skipping the pre-mask, not just for time management, but also to not be too aggressive with the strategy. The application of an aloe/clay mask may help to sooth the skin post-injection.

One may also consider using dermal roller application of acne formula 1 to 2 times a week.

My Own Strategy

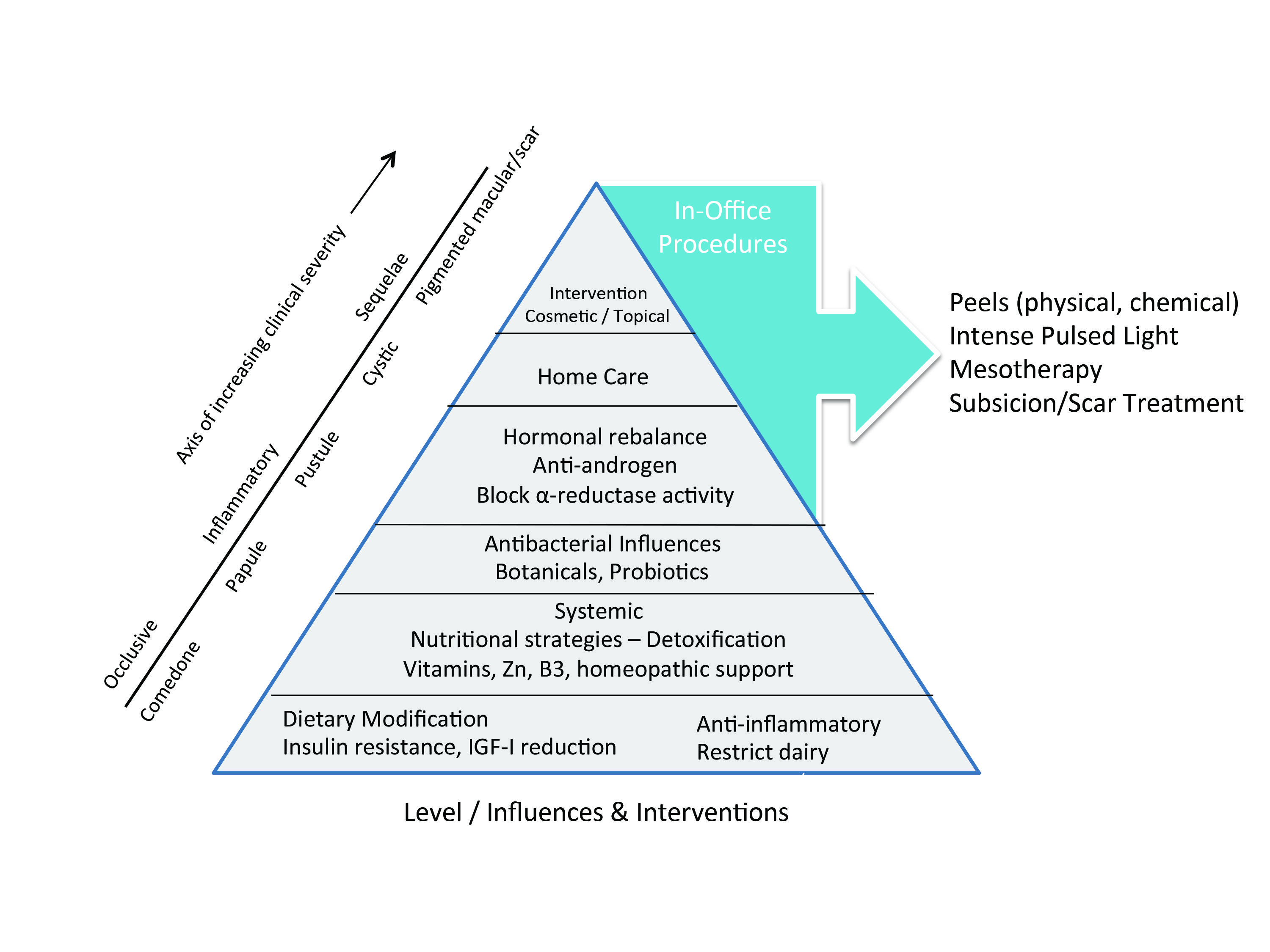

Please refer to Figure 4 for my recommended clinical approach and treatment prioritization with acne patients.

Figure 4. Clinical Management / Therapeutic Triangle

For Home Care:

- AM – Slightly acidic facial cleanser, toner, AHA, or sunscreen (non-comedogenic) moisturizer

- PM – Cleanser, exfoliator, toner, and AHA moisturizer or topical retinoid

- Weekly, 1-2 times per week – Clay-based, glycolic acid peeling mask, to be left on for 30 minutes

Ideally, this mask is used for 2-3 weeks as a pretreatment before cosmetic care, to help reduce sebum expression, regulate inflammation, and facilitate turnover of the stratum corneum and epithelium.

For Peels:

- Physical Peeling

- Microdermabrasion: I suggest 1-2 sessions. I do this with a dermal infusion device that allows dermabrasion and infiltration of the skin with salicylic acid.

- Chemical Peeling

- Glycolic acid peels: 10, 20, 35 or 70% glycolic acid. I do these peels weekly for a total of 4 weeks. I also include 2 IPL sessions, mid-way through the peel cycle.

For Scar Treatment:

I suggest using TCA (trichloroacetic acid) or pixelated laser; or, for deep, anchored scars, subcision using specialized needle (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Subcision Needle

Subcision involves inserting a needle through the surface of the skin and cutting the fibrous scar tissue that is pulling down the surface skin. This allows the skin to be lifted, since it is no longer bound down.

The subcision technique works best for rolling acne scars and boxcar acne scars. Multiple sessions are required, such as 3, about 1 month apart. The most common side effect is bruising of the skin. Saline injections are a form of a subcision, wherein bacteriostatic saline is injected within the skin. The act of injection will stretch out the scar. When this process is performed multiple times, the act of stretching the scar will ultimately loosen up the scar underneath the skin, thus allowing the skin to rise.

For Mesotherapy:

After the peel cycle, I suggest 6-8 (if required) mesotherapy facial treatments. It can also be done immediately following physical or chemical peeling and should be followed by localized treatment of trouble spots and nappage technique of entire face.

Conclusion

A complex, multifactoral clinical condition such as acne requires an approach that addresses all aspects of the condition and its sequelae. Clinical outcomes can be dramatically improved by treating this condition not only from the inside out, as our guiding principles dictate, but also to skillfully and with therapeutic rationale, externally treat the cosmetic aspects of acne vulgaris. For practitioners looking towards incorporating more cosmetic strategies into the chronic care practice, the acne patient can represent a very rewarding clinical bridge.

Michael Rahman, BSc, ND is a naturopathic doctor, practicing for 18 years, who owns clinics in Toronto and Durham region, Ontario. After completing his Bachelor of Science at McMaster University, he attended the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine. Michael’s practice focuses on biological medicine, healthy age management, and cosmetic medicine. The owner of Pinewood Institute, he teaches naturopathic doctors across North America mesotherapy for pain management and cosmetic medicine, cosmetic care, bioidentical hormones, and advanced homotoxicological approaches to disease. Dr Rahman is also the chief medical officer for Healthy and Active – the metabolism program customizing dietary approaches from blood chemistry.

Michael Rahman, BSc, ND is a naturopathic doctor, practicing for 18 years, who owns clinics in Toronto and Durham region, Ontario. After completing his Bachelor of Science at McMaster University, he attended the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine. Michael’s practice focuses on biological medicine, healthy age management, and cosmetic medicine. The owner of Pinewood Institute, he teaches naturopathic doctors across North America mesotherapy for pain management and cosmetic medicine, cosmetic care, bioidentical hormones, and advanced homotoxicological approaches to disease. Dr Rahman is also the chief medical officer for Healthy and Active – the metabolism program customizing dietary approaches from blood chemistry.

References

- Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2005:1303-1304.

- Voss JG. Acne vulgaris and free fatty acids. A review and criticism. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109(6):894-898.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(3):323-333.

- Tosti A, Grimes PE, Pia de Padova M. Color Atlas of Chemical Peels. Dusseldorf, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2006.

- Papakonstantinou E, Aletras AJ, Glass E, et al. Matrix metallo- proteinases of epithelial origin in facial sebum of patients with acne and their regulation by isotretinoin. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):673-684.

- Caillon F, O’Connell M, Eady EA, et al. Interleukin-10 secretion from CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells is downregulated in patients with acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(2):296-303.

- Melnik BC, Schmitz G. Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor- 1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(10):833-841.

- Shepherd PR. Secrets of insulin and IGF-1 regulation of insulin secretion revealed. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 1):e1-e2.

- Smith TM, Gilliland K, Clawson GA, Thiboutot D. IGF-1 induces SREBP-1 expression and lipogenesis in SEB-1 sebocytes via activa- tion of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(5):1286-1293.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, et al., High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):207-214.

- Healthy & Active. The Metabolism Program. www.Healthy-active.com. Accessed February 15, 2014.

- Fivenson DP. The mechanisms of action of nicotinamide and zinc in inflammatory skin disease. Cutis. 2006;;77(1 Suppl):5-10.

- Pohit J, Saha KC, Pal B. Zinc status of acne vulgaris patients. J Appl Nutr. 1985;37:18-25.

- Michaëlsson G, Juhlin L, Vahlquist A. Effects of oral zinc and vitamin A in acne. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(1):31-6.

- Leyden JJ, Shalita A, Thiboutot D, et al. Topical retinoids in inflammatory acne: a retrospective, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled, photographic assessment. Clin Ther. 2005;;27(2):216-224.

- Dawson AL, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris. BMJ. 2013;346:f2634.

- Rahman M. Chemical Peels [training manual]. Pinewood Institute for the Advancement of Natural Therapies; 2005.

- Benner N, Sammons D. Overview of the treatment of acne vulgaris. Osteopathic Family Physician. 2013;5(5):185-190.

- Kim BJ, Lee HG, Woo SM, et al. Pilot study on photodynamic therapy for acne using indocyanine green and diode laser. J Dermatol. 2009;36(1):17-21.

- Tzung TY, Wu KH, Huang ML. Blue light phototherapy in the treatment of acne. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20(5):266-269.

- Ross EV. Optical treatments for acne. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(3):253-266.

- Haedersdal M, Togsverd-Bo K, Wulf HC. Evidence-based review of lasers, light sources and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(3):267-278.

- Graupe K, Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP, Zaumseil RP. Efficacy and safety of topical azelaic acid (20 percent cream): An overview of results from European clinical trials and experimental reports. Cutis. 1996;57(1 Suppl):20-35.

- Le Coz J, Lam VV. Mesotherapy & Lipolysis: A Comprehensive Clinical Approach. Singapore, Phillipines: Esthetic Medic Pte Ltd; 2008.

- Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):734-740.

[Bio]: