A Baker’s Dozen by 2025: We Can Do This. We Have to Do This. (Part 2 of 2)

David Schleich, PHD

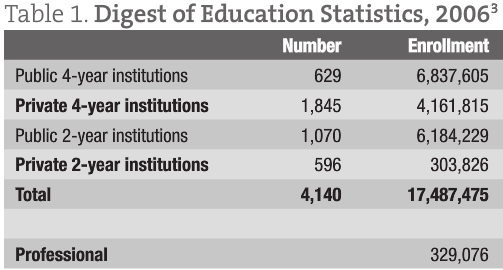

Last month we considered what it would take to get a half dozen more ND programs operating by 2025. The rising role of for-profit educational enterprises in higher education is not new to this challenge, but its sector strength has grown significantly since the early days when NCNM, Bastyr University (BU), CCNM and SCNM started up. In fact, there are more than 1700 organizations in North America loosely described as “corporate universities”, some of which definitely have an eye on many professional and vocational preparation program opportunities, including the rich, specialized market of “natural medicine education” from the professional doctorate credential to quick allied healthcare certificates. These private sector learning entrepreneurs are accelerating post-secondary transformation.1 Jeanne Meister, president of Corporate University Xchange (CUX) predicted a decade ago that by the year 2010 private educational “institutes for learning” would actually outnumber traditional universities.2 She wasn’t far off as the Institute for Education Sciences (IES) statistics for 2006 point out in the accompanying table.3

This enormous sector in the US higher education landscape will eventually pay closer attention to the draw of naturopathic medical curriculum, especially in states where a regulatory or public policy framework provides some assurances of work for graduates willing to spend the tuition dollars to earn a first professional degree.

Corporate universities do not seem to want their primary function only to be granting degrees though. Rather, they also know they have to “partner with universities to provide customized programs for major job families, usually within their organizations.”2 However, it is in the interactivity, along those points where the public and the private meet, that influence is sharply felt and anxieties run high. Old certitudes continue to be nudged by new patterns. It is where the nudges are strongest that a naturopathic medical program will pop up. It is highly probable that the Council on Naturopathic Medical Education (CNME) will be asked to reconsider its preference for non-profit entities, not unlike the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s (LCME) having been challenged to accept early for-profit osteopathic colleges such as Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine (RVUCOM) in Parker, Colorado. That school was founded and is owned by Yife Tien, COO of the American University of the Caribbean (AUC) located in St. Maarten, itself a for-profit, higher education entity. Ross University operates an LCME-accredited medical program in the Caribbean and has been successful in attracting high-profile medical educational professionals including, most recently, the former dean of naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University.

Another influential pattern has been the growing attention paid by private higher education entrepreneurs to the utilitarian aspect of higher education for realizing national economic goals. While those of us who’ve been in the naturopathic field for a while cannot soon easily imagine a landscape in which naturopathic medical professionals are properly factored into economic strategies related to health promotion, there lingers an anxiety that for-profit private education advocates and investors constitute a kind of phalanx of “academic capitalism”.4 One can be neo-liberal and have the perspective that the impersonal, inexorable and global nature of the market will inevitably invade our corner of higher education no matter what we do to defend the certainty of traditional non-profit university and college mandates and character. Alternatively, we can be more inclined to a post-Keynesian mindset. In any case, higher education is crucial for techno-science, industrial policy, and the intellectual property strategies that constitute the heart of corporate, global societies. Such pressures hatch systemic change and stimulate the very kind of convergence of science and technology, curriculum, access, finance, and modified autonomy in which private higher education can thrive.

Zinser wrote over 20 years ago about the potential conflict of interest issues that can arise in such environments, particularly in those relationships between academia and industry.5 However, it is in that penumbral zone flickering alongside the traditional role of the universities,6-8 and the restated significance of the higher education institutes in the “smart, swift creation and use of information in a global economy of markets, competitors, and production technologies” that private higher education finds new fertile ground.9 Understanding key aspects of how that fertile territory gets invaded and secured is an important dimension of the deliberations here.

It can be quite useful to explore this growing recognition of private higher education as a “central element” of postsecondary educational systems.10 Private higher education is well funded, agile and aggressive. We can take a moment to juxtapose the key characteristics of institutions, which, in identifiable ways, reflect what some think could happen. In the interests of seeing just how far the certainty about such an interest by private, for-profit organizations to jump start a naturopathic program, it is tempting to remember some high-profile international private examples (such as INSEAD in Paris, Waseda or Keio in Japan, Yale in the United States, Ateneo de Manila in the Philippines, or Javieriana University in Columbia). There is also a new naturopathic college incubating in Manila, its funding coming directly from a for-profit, multidiscipline, allopathic enterprise called TotalMed. Happily, this latter company is committed to spinning off its new school into a non-profit, and inviting the CNME to consider generating standards for international school clients.

We might be alarmed at these intrusions into higher education by business. Our inclination is to embrace the social good which our schools can do, and to eschew any idea of accruing equity for any individual or group from the naturopathic community. Clark outlined a useful typology of 3 basic value sets (specifically social justice, competence, liberty … and perhaps loyalty) that help to position colleges and programs like ours in society.11 These value sets are frequently cited as the debate emerges about the “social good” (or lack of it) that accompanies private universities, particularly of the for-profit kind. This values typology is enhanced even further by Clark’s now famous “triangular model”, outlined a decade later in the landmark study Places of Inquiry in which he contemplates the strain within academia generated by conflicting pressures among the sometimes contrary imperatives of education for the professions, general liberal education, and research training and practice.12

As well, Knowles’ discussion about the “emerging entrepreneurship” within colleges (in terms of their response to the very private-sector-like impacts of markets and revenue) is another handy tool for a closer look at the manifesting of private higher education in our world. The goal is to understand those forces which are driving what Altbach has described as “the logic of today’s market economies and an ideology of privatization.”13

The responsibilities of private higher education (that is, the complex conversation about public and private good) are very much part of the parameters of private higher education. Gorostiaga, as a case in point, argues that public, social good is not a commodity.14 Buchbinder states that “the objectives of higher education that are expressed as the production and transmission of knowledge as a social good are being replaced by an emphasis on the production of knowledge as a market good, a salable commodity.”15 Whatever impact this tension is shown eventually to have on academic autonomy and collegiality, the tremendous differentiation in private higher education being witnessed by students of higher education as a global phenomenon could find very precise manifestation in one of our proposed corners of America as a potential launch pad for the half dozen new programs I proposed at the outset.

Notwithstanding the possibility of a for-profit university or college seizing on the promise of a naturopathic program, and even seeking candidacy from the CNME, a first determination for us or for a private for-profit group is whether to launch a stand-alone single-program college such as SCNM or NCNM and John Bastyr College at their inceptions, or, as occurred in Lombard and Bridgeport, as part of an existing institution. Given that the latter poses a less arduous pathway both logistically and financially, the first step would be to conceive and develop, with consensus from an initial, interim governing body, a detailed proposal for integration of program and facilities with a university which has a major role in health sciences education and enough respect for naturopathic medicine as a distinct heterodox medical system to champion its purposes. Such a proposal would require the support of both the university’s administration and senate. Not only would the program have to be seen as a money-maker, but also as a “fit” within the program mix, short and long-term.

The proposal would then be sent to the State agency responsible for program review and funding consideration. As part of the normal degree authorization process for an institution in a state system, the department responsible would ask for comments on human resource needs in that sector and on the appropriateness of the educational program in relation to the scope of naturopathic practice and its intersection with primary care in that state. Soon thereafter we could expect that the Department of Health within the State apparatus would be consulted for its views on the proposed inclusion of a naturopathic program within a public sector university.

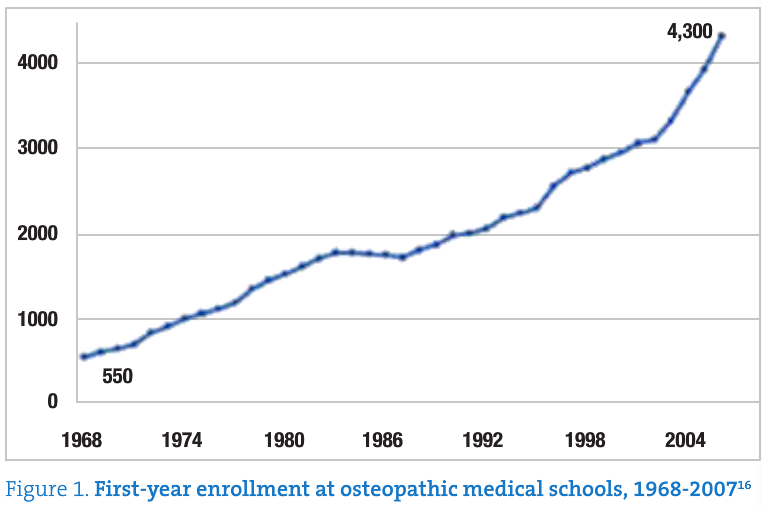

How likely, then, would it be that ND programs would find their way into public institutions? The experience of the osteopathic profession warrants a quick review here. Those who recall the pathway of the osteopathic doctor in America recall the first such migration from a stand alone college to a public institution. The Michigan College of Osteopathic Medicine in Pontiac affiliated by an act of the Michigan legislature in 1969, and by 1971 was opened as a faculty of the University of Michigan, the first of its kind in the US. Within less than 4 decades there were 25 osteopathy colleges in 31 locations.

This remarkable growth, of course, has not been without controversy. J.D. Howell, for example states the concern pointedly:

“If osteopathy has become the functional equivalent of allopathy (meaning the MD profession), what is the justification for its continued existence? And if there is value in therapy that is uniquely osteopathic, why should its use be limited to osteopaths?17

We have our work cut out for us. The dynamics of expanding our profession so dramatically are daunting. Burton Clark writes eloquently about the dynamic impact with which higher education systems evolve among state or bureaucratic influences, the pressures of collegiality among the professoriate and administrative staff, and the market generally.11 Clark’s commentary about normative/professional isomorphism (a term which talks about how those creating new programs rely on what they know from their own experience) is the particular perspective assisting us to understand what lies ahead. The documents of our first 7 colleges quickly yield up a picture of our early college administrators and teachers reflecting the norms of their own previous institutions, particularly in terms of curriculum preferences, organizational structures and terminology; however the persistent “individualism” of professional practitioners appears at the same time in those documents.

For example, at a meeting of 3 Ontario Naturopathic Association members in 1978, the same year that NCNM decided to set itself up permanently in Portland, Bastyr College was formed in Seattle, and OCNM launched its pre-ND program at the University of Waterloo and its part-time program in Toronto, the Canadians from Ontario were lauding the “individualism and customizing genius of Drs. Boucher, Bastyr and Carroll” advocating that “our new schools in the U.S. and Canada must remember in their very corridors that naturopathic medicine is a medicine of individualists.”18 In that same meeting the Ontario naturopathic doctors admonished their colleagues, “If we don’t keep up the university standard, like we used to have at Western States and National in Chicago, our schools will be weak and the for-profit diploma millers will steal our topsoil.”18

In earlier NDNR columns I have written about how this topsoil gets formed in the first place. For example, Levy’s ideas of “folding the normative and mimetic isomorphism into a broad noncoercive category” capture the issue here quite nicely.19 Esoteric academic categories such as “isomorphism” boil down to these facts.19,20 First, in Ontario, Oregon and Washington, higher education state officials, university and college officials, and regulatory agencies had virtually no direct involvement in the founding and operation of the new programs and schools. The shape of the new schools was “mimetic”, in that the founders imitated what they themselves had experienced. These days ‘mimetic isomorphism’ manifests as compliance. CNME standards are published and strong. Regional accreditor standards are published and strong. Whoever takes on the challenge of getting a half dozen new programs up and thriving by 2025; whoever holds up a target of 1,000 new NDs a year entering the profession, year over year; whoever those new leaders will be, there will be little doubt in their minds that time is short, and even less doubt that the time to begin this bold enterprise is now.

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice presi-dent academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice presi-dent academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

- Corporate University Xchange Web site. Available at http://www.corpu.com.

- Morrison JL, Meister JC. Corporate universities: an interview with Jeanne Meister. Vision. 2000:22-31.

- U.S. Department of Education Institute for Education Sciences (IES). Digest of Education Statistics, 2006. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Slaughter S, Leslie L. Academic science and technology in the global marketplace. In: Slaughter S and Leslie L. Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies, and the Entrepreneurial University. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 1997:23-63.

- Zinser EA. Potential conflict of interest issues in relationships between academia and industry. In: Bennett JB, Peltason, JW eds. Contemporary Issues in Higher Education. New York: American Council on Education and Macmillan Publishing; 1985:169-213.

- Newman JH. The Idea of a University. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, (originally published in 1873). 1976;124-155.

- Flexner A. Universities: American, English, German. New York: Oxford University Press (originally published in 1930). 1968:3-36.

- Kerr C. The Uses of the University. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1982:1-45.

- Blackman C, Segal N. Industry and higher education. In: Clark B, Neave G, eds. The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Volume 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press.1992:841-851.

- Altbach PG. Private Prometheus. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999:vii.

- Clark BR. Values in Higher Education: Conflict and Accommodation. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Center for the Study of Higher Education; 1983.

- Clark, BR. Places of Inquiry: Research and Advanced Education in Modern Universities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press;1995.

- Knowles J. A matter of survival: emerging entrepreneurship in community colleges in Canada. In Dennison JD, ed. Challenge and Opportunity: Canada’s Community Colleges at the Crossroads. Vancouver: UBC Press; 1995:2.

- Gorostiaga X. In search of the missing link between education and development. In: Altbach PG, ed. Private Prometheus. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999:192.

- Buchbinder H. The market oriented university and the changing role of knowledge. Higher Education. 1993;26(3):331-347.

- Gevitz N. The DOs: osteopathic medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008.

- Howell JD. The paradox of osteopathy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(19):1465-1468.

- Ontario Naturopathic Association. Minutes of a meeting held on August 4, 1978.

- Levy DC. Alternative private-public blends in higher education finance. In: Levy DC, ed. Private Education: Studies in Choice and Public Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1986:19.

- Levy DC. Private institutions of higher education. In: Clark B, Neave G, eds. Encyclopedia of Higher Education. Oxford: Pergamon; 1992.