The Case of the “Daysleeper”

Catherine Darley, ND

When patients waiting in a general practice are surveyed, 35% of them will say they have sleep complaints, although that may not be why they are visiting the physician.1 Unfortunately, unresolved sleep complaints can have a broad impact on health. For about 1 in 5 Americans, their work situation makes it impossible to get normal nocturnal sleep because they are working during those hours.2 This circadian disruption can cause many different types of symptoms and lead to increased health risks. Because this is a common problem, with negative consequences, today I would like to highlight of case of a shift worker and the treatment approach.

Meet Sarah

Meet Sarah, a 36-year-old single woman who works nights in emergency medicine. Her shift is 6:30 pm to 7 am, 12 nights per month. She typically will work 2 to 3 nights in a row and then will have 3 to 4 nights off. Historically, Sarah has always being a “light sleeper,” with sleep difficulties twice a month, and identifies herself as a “morning person.” During professional school, insomnia increased to 1 to 2 nights per week, and now on the night shift she is having difficulty most nights.

Her bedtime is 8:30 am on work nights and varies from 10 pm to 3 am on days off. She finds it easy to fall asleep in the morning after work but has more difficulty sleeping at night. She often feels anxious about sleep before her nocturnal bedtime and will take up to 2 hours to fall asleep. She reports no history of anxiety or any current problems at other times of the day. On those nights of sleep difficulty, her mind is very active. She will take diphenhydramine, zolpidem tartrate, or alprazolam 3 or more times each week to help her sleep, usually for nocturnal sleep. She identifies that she does best with 7½ hours of sleep nightly, and a sleep diary shows that her total sleep varies from 5 to 10½ hours. Sarah has 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per week and consumes 1 to 3 caffeinated beverages a day, on waking and at about 1 am on work nights. The Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep Scale shows that she is having some thoughts that can promote insomnia such as “I am worried that I may lose control over my sleep.”

Sarah is concerned about the social consequences of her shift work schedule and wants to be awake during the day on her days off so she can stay connected to friends and family. She shares an apartment, so she needs to be quiet at night, while her roommate sleeps.

Clinical interview and physical examination rules out other sleep disorders, including sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, parasomnias, and hypersomnias. She is diagnosed with circadian rhythm sleep disorder shift work type and with psychophysiological insomnia.

Treatment Strategy

The first goal is to create a routine that will have less variability in sleep times and thereby will better synchronize sleep and alertness systems. In discussion, we identified a block of hours when she could sleep regardless of whether it was a workday or not. On days off, her prescribed bedtime was 2 am, with a wake time of 9:30 to 10 am. On workdays, her bedtime was 8:30 am, with a wake time of 4:30 pm. In addition, she will take a prophylactic nap in the late afternoon before her first work shift.

Another component of the treatment plan was to help shift her sleep earlier by taking 1 mg of melatonin at 1 am when she had a 2 am bedtime. In addition, Sarah used blue-light blocking goggles as soon as her shift ended in the morning, so her natural melatonin would not be inhibited by the daylight.

We also used cognitive techniques to help her accept a later bedtime and fall asleep more easily. The first assignment was to think through what things she could do on her own when awake until 2 am at home and what activities she wants to be sure to do during day hours with other people. Second, we discussed sleep-promoting activities she could use to fall back asleep if she found herself awake during sleep hours. These included (1) slow breathing for a count of 3 in and 3 out (slowing the breathing, as in biofeedback training), (2) personally visualizing herself sleeping, (3) telling herself a gentle story that focuses the mind on something pleasant and thereby blocks out the racing thoughts, or (4) performing progressive muscle relaxation. She was instructed to choose 1 or 2 of these to learn, as they are a skill, and skills take time to learn and become good at.

First Record of Contact

At her 2-week follow-up appointment, Sarah says she is sleeping a much higher percentage of the time she is in bed. More importantly, she is sleepy at bedtime and is therefore less anxious. She used the sleep-promoting practices but only needed them 3 or 4 nights. She used the sleep medications much less. The schedule does not allow enough time in bed, and she says she really thinks she needs 8½ to 9 hours of sleep nightly, not the 7½ previously identified. Her total sleep time varied from 5 to 9 hours.

The treatment plan was to increase sleep hours on days off, from 2 am to noon, while continuing with the 8:30 am to 4:30 pm sleep time on work nights. For insomnia, we instituted more cognitive behavior strategies, including making her bedroom comfortable and dark for daytime sleep, reserving the bed and bedroom just for sleep, and avoiding looking at the time during sleep hours.

Sarah was also instructed to use another cognitive piece that has been successful with many patients who have an active mind at bedtime. The exact instructions are to spend 10 minutes, 2 to 3 hours before bedtime, writing down the thoughts that come up at bedtime. Then, in the night tell yourself “I already thought about that and will have time tomorrow. Now’s time to sleep.” The goal of this is to ensure that there is time during wake hours to think things through and then insulate sleep time from that mental processing.

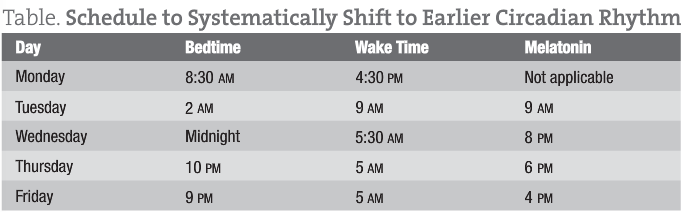

Sarah had been assigned a day shift for the next month and needed to switch during 2 days off. So, we created a schedule that would systematically shift her circadian rhythm earlier (Table).

Second and Last Record of Contact

It is clear to Sarah that she does much better when she can sleep at night and work during the day. Her supervisor has given her the option of continually working nights or of alternating a month of day shift and then a month of night shift. Sarah will be going into a month of night shift now. She found that the journaling helped to set her thoughts aside. The only night she “slept lighter” was the first night before the workweek started. She is not quite getting the 8½ hours of sleep she does best with owing to evening social activities.

The treatment plan was brief. The first focus was to continue the process of shifting her thinking to sleep-promoting thoughts. Sarah was instructed to pause if she found herself thinking a negative sleep thought during the day and then ask herself “Is that really true?” and be open to other possibilities. Second, we discussed the ways that Sarah feels better with 8½ hours of sleep and discussed how to get more sleep by napping strategically, moving social activities earlier when possible, and ensuring 8½ hours of sleep on vacations and holidays. Over the next couple of days, she would shift back to a late sleep schedule and block morning light to aid in this schedule change.

Concluding Comments

Helping shift workers sleep well (whatever time they are sleeping) is very important, both for their individual health and well-being, as well as for our society, with so many people working shifts. What is so interesting is that, if 2 people present on the same shift work schedule, they will need different plans because of their intrinsic sleep differences and because of their social situation. The principles that have been helpful in my practice are the strategic controlling of light exposure, precise timing of low-dose melatonin to shift the circadian phase, addressing environmental sleep disturbances, and performing cognitive behavior techniques for insomnia—all in the context of the individual.

Catherine Darley, ND is the director of The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. The year 2013 marks her 20th year in the sleep field, in varying roles. Dr Darley provides sleep care for people of all ages and specializes in insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders. She also provides sleep education to public groups and health professionals, as well as fatigue management consulting to corporations. Dr Darley currently serves on the executive committee of Start School Later, a national effort to align school start times with circadian physiology of teens. She is a past board member of the Washington Association of Naturopathic Physicians. Dr Darley lives in Seattle with her young family and enjoys sleeping well every night.

Catherine Darley, ND is the director of The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. The year 2013 marks her 20th year in the sleep field, in varying roles. Dr Darley provides sleep care for people of all ages and specializes in insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders. She also provides sleep education to public groups and health professionals, as well as fatigue management consulting to corporations. Dr Darley currently serves on the executive committee of Start School Later, a national effort to align school start times with circadian physiology of teens. She is a past board member of the Washington Association of Naturopathic Physicians. Dr Darley lives in Seattle with her young family and enjoys sleeping well every night.

References

- Hossain JL, Shapiro CM. The prevalence, cost implications, and management of sleep disorders: an overview. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(2):85-102.

- Monk TH. Shift work. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2000:471-476.