Skin Cancer Review

Lidia Wiersum, ND, FABNO

Many types of skin cancer are preventable and treatable, so it is essential that we as NDs take an active role in educating our patients about the importance of skin cancer prevention and treatment. This article focuses on basal and squamous cell carcinomas and malignant melanomas.

Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers

Each year, 1.3 million cases of either of the two most common types of non-melanoma skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), are diagnosed. This is likely an underestimation, as many physicians remove and treat these forms of cancer without determining proper histopathology or reporting them. BCC is 4 times more common than SCC, and the incidence of both cancers increases near the equator. Blue-eyed, fair-skinned, blond- or red-haired individuals are at increased risk, with a male-to-female risk ratio of 4 to 1.

Risk factors include:

- Solar radiation (UVB and UVA): UV radiation is the most important etiologic factor for BCC and SCC, with more than 90% of skin lesions developing in sun-exposed areas. A strong association between the amount of lifetime exposure, its timing and skin type has been observed, suggesting that approximately 40% of people who live to age 65 will develop at least one non-melanoma skin cancer.

- Chronic irritation/wounds: Skin diseases with a chronic inflammatory or irritant course are associated with SCC and include conditions such as venereal granulomas, syphilis, SLE, chronic ulcers and old burn scars. Oral cavity SCC can be induced by the irritation secondary from chewing tobacco.

- Ionizing radiation: In the past, acne, hirsutism and tinea capitis were treated with x-ray therapy, causing large invasive deforming skin cancers in some patients later in life. SCC on the fingers of dentists secondary to occupational exposures was also seen. Such uses of x-ray therapy have been discontinued or modified, with marked reduction in long-term side effects.

- Immunosuppression: Patients with immunodeficiencies (e.g., organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapies, patients with hematological malignancies post stem cell transplant) are prone to develop de novo malignant neoplasms that behave aggressively.

- Hereditary factors: These include xeroderma pigmentosum, an autosomal recessive disease with defects in DNA repair enzymes, and basal cell nevus syndrome, an autosomal dominant trait resulting in multiple BCC lesions appearing over the face, arms and trunk of young adults.

- Viral infections: SCC of the oral cavity, genitals and anal region is strongly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18, which is sexually transmitted.

- Other risk factors include previous history of actinic keratosis, with 1% risk of becoming SCC; and chemical carcinogens such as arsenic and coal tar.

Clinical pearl: Skin malignancies that arise de novo are frequently associated with more aggressive behavior and higher metastatic propensity, requiring more aggressive treatment options.

Histopathology and Clinical Presentation

BCC is the most common skin cancer type. It arises from the immature pluripotential cells of the epidermis or from the outer root sheath of hair follicles and features masses of compactly arranged basaloid cells. There are several subtypes:

- Nodular (62%): slow-growing lesion that appears on the face or neck as a waxy papule with pearly, rolled border and overlying telangiectasia. As the lesion enlarges, it may ulcerate in the center, causing what is known as the “rodent ulcer”

- Sclerosing (35%): lesions that appear yellowish in color, closely resembling scars and lacking telangiectasias, pearly appearance or clear borders

- Superficial (3%): multiple lesions that appear flat, erythematous and scaly, with areas of brown or black pigmentation, resembling eczema and psoriasis

Clinical pearl: It is often difficult to differentiate between BCC and SCC based on clinical appearance. As these malignancies could potentially require different treatment, proper excision and histopathological evaluation is important.

SCC is the second most common skin carcinoma. The primary lesion manifests as a pink/red indurated papule or plaque. It is often preceded by actinic keratosis, a rough scaly papule or plaque that may be easier to diagnose by touch than sight. The lesion then expands rapidly, producing a large nodule that eventually ulcerates and metastasizes to a local draining lymph node.

In 1775, London physician Percivall Pott was the first to link chemical exposure to cancer when he identified the occupational exposure to chimney soot as the cause of SCC arising on the scrotum of chimney sweeps. His analysis of SCC etiology is often cited as the beginning of cancer research and is probably one of the first accurate identifications of a human carcinogen.

Although SCC and BCC have similar risk factors, remember that unlike BCC, the behavior of SCC correlates with its etiology. For instance, if SCC arises from sun-damaged skin, it tends to be more indolent with lower metastatic potential. However, lesions that arise from chronic ulcers, burn wounds or radiation have much higher propensity for blood-borne metastasis. An even worse prognosis is associated SCC that arise de novo, especially in extremities with high incidence of lymph node invasion. For actinically induced SCC, the incidence of metastasis is less than 3%; however, it jumps to 35% for non-actinically induced lesions.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis ultimately requires skin biopsy and histological conformation. If the first biopsy is negative and the tumor is still suspected, a deeper biopsy is necessary.

Staging

TNM system for classification of cutaneous carcinomas is used (T = extent of primary tumor, N = absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node involvement, M = absence or presence of distant metastases), although it is not ordinarily required for BCC as this tumor rarely metastasizes. However, diameter size, clinical features and border description have to be noted, as they determine the prognosis. For SCC, the staging is based on clinical examination of the lesion and regional lymph nodes. The prognosis is worse if the tumor is recurrent, arises from a previously damaged area of the skin, measures greater than 4mm thick or 2cm in diameter, and occurs in patients who are immunosuppressed.

Treatment Options

The goal of treatment for BCC and SCC is cure of the tumor with maximum preservation of function and cosmesis. Surgical excision with assessment of margins remains the gold standard. It is crucial to have negative (clear of involvement) margins, as residual disease markedly increases the rate of recurrence. Lesions that arise de novo require wide excision and lymphadenectomy or sentinel lymph node biopsy. In complex, recurrent cases, Mohs’ surgery with micrographic mapping and layer-by-layer removal of the tumor is utilized. Note that for SCC, radiation is equally as effective as excision, except when the bone or cartilage is involved. Otherwise, radiation is reserved for cases where patients are not good candidates for surgical resection. In patients with low-risk, superficially spreading BCC, topical chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil is used. Laser electrodesiccation and curettage or cryosurgery is no longer widely recommended, as they may render a lower cure rate.

Malignant Melanoma

Melanoma is a highly invasive and often fatal malignancy of the melanocytes. The incidence of melanoma has increased a drastic 690% from 1950 to 2000. According to the American Cancer Society, more than 60,000 new cases of melanoma are diagnosed yearly in the U.S., with 8,000 resulting deaths. The increased incidence is related to changes in sun exposure patterns and perhaps to the reduction of the ozone layer. Individuals with a fair complexion and blond hair, those who live closer to the equator and those who burn easily, have a substantially higher risk of developing melanoma.

In declining order of importance, the risk factors include:

- Changing preexisting mole: About 70% of patients with melanoma have a preexisting nevus at the primary tumor site

- Solar radiation (UVB and UVA): Several observational studies suggest that UV light may be a critical factor in the development of melanoma, and yet there is a debate in the literature regarding whether it is the sunburn frequency and intensity, or the cumulative sun exposure that is the contributing factor.

- Hereditary factors:

- Family history of melanoma: Approximately 10% of all melanoma cases occur in persons with familial predisposition.

- Familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome (FAM-M), previously called dysplastic nevus syndrome: This form of malignant melanoma is distinguished by multiple, large (>5mm diameter) macular/papular moles that have irregular borders and are variable shades of brown, black and red

- Fair complexion, type I skin which is porcelain white and always burns and never tans

- More than three blister sunburns before age 20 and/or more than three outdoor jobs as a teenager

- Large number of nevi and/or large size (5-10mm) nevi

- Tendency for marked upper back freckling

- Genetic mutation in repair genes causing Xeroderma pigmentosum

- History of actinic keratosis

Note that the presence of one or two factors increases the risk of developing melanoma by 3-5x; with the presence of three factors, the risk of developing melanoma is more than 20%.

Histopathology and Clinical Presentation

There are several types of melanoma. For this discussion, melanoma is classified as the following:

- Superficial Spreading Melanoma (SSM) represents approximately 70% of all melanomas. It commonly arises from a preexisting, changing lesion and is associated with dysplastic nevi. SSM usually appears flat, multicolored with an irregular notched border, and averages 2cm in diameter. SSM may have a relatively long natural history, being in radial growth phase (RGP), which is associated with little metastatic potential. However, later in the course it may develop a nodule and transition into the Vertical Growth Phase (VGP), which is associated with high metastatic potential.

- Nodular Melanoma (NM) is the second most common type and represents approximately 20%-25% of all cutaneous melanomas. It most often arises de novo on the trunk of men, and appears dark and uniform in color. NM is biologically more aggressive and does not have a radial growth phase, which means rapid evolution to vertical growth and invasion of the dermis, blood and lymphatics.

- Lentigo Maligna Melanoma (LMM) arises from the precursor lesion, lentigo maligna (Hutchinson’s freckle) and represents approximately 10% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas and is the most benign cutaneous melanoma. It is found in elderly individuals over sun-exposed areas and is generally large (3-4cm in diameter) and flat, with irregular borders and variable color from tan to dark brown. Hypo-pigmented areas in the lesion represent areas of regression.

- Acral Lentiginous Melanoma (ALM) is rare and arises on palmar, plantar and subungual skin. ALM constitutes a substantially higher proportion of melanomas in dark-skinned individuals and accounts for close to 50% of melanomas in African Americans, Hispanics and Asians. The lesions are large (3cm in diameter), with irregular borders, and may ulcerate and fungate. Although similar in appearance to LMM, these lesions are more aggressive.

Diagnosis

It is often difficult to determine a freckle vs. a mole vs. a malignant lesion; always err on the side of caution and do a proper biopsy. Excisional biopsy is the preferred method, and will have narrow margins. It is critical to cut into the subcutaneous fat and have proper orientation to preserve the skin lines. Incisional biopsy is reserved for large lesions on the face, hands and feet, and is done with a punch or cut.

Due to the variability of clinical presentation, it is crucial to understand the history relating to the lesion and remember the ABCDEF mnemonic:

A: asymmetry in shape

B: border changes and irregularity

C: color variation – often with a number of shades of black, brown, blue, red and progressive pallor within a pigmented lesion

D: diameter change, greater than 5mm

E: evolution – i.e., change in appearance, size, color

F: functional change – i.e., bleeding, crusting, ulcerating, painful, itching

Clinical pearl: Ulceration of the lesion is a bad prognostic sign, as it means that the cells are dividing so fast the tissue is necrosing or invading the blood vessels, causing bleeding. Poorer five-year prognosis is reported, with a drop from 80% for non-ulcerated melanomas to 55% for ulcerated lesions.

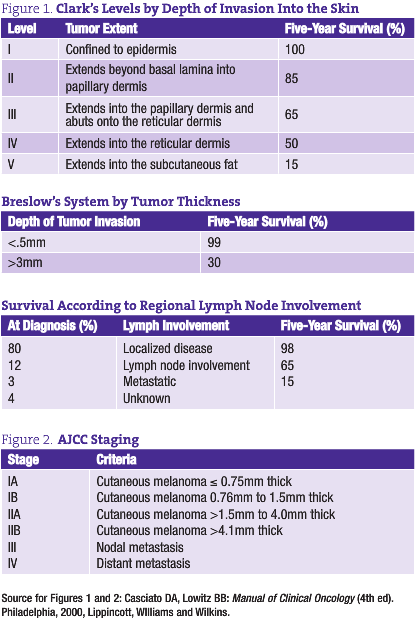

Further evaluation of melanomas is based on the histological features, with emphasis on depth of invasion into the skin, thickness, margin assessment and mitotic rate. Clark’s classification describes how deep into the skin the tumor has penetrated, and is now mostly used for thin, <1mm lesions. Breslow thickness, now the preferred method of classification, measures in millimeters the tumor size from the granular layer of the epidermis to the deepest part of the tumor (see Figure 1). In general, the deeper and thicker the primary tumor, the more likely it is to have metastasized. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging is complex, with direct correlation between worsening of survival and increase in staging (see Figure 2).

Melanoma Treatment

Surgery

The treatment for malignant melanoma was first defined in 1937. For early-stage melanomas, surgical resection remains the principal curative therapy. Unfortunately, until the late 1980s, these surgeries required a 5cm (wide) margin, with resection deep into the subcutaneous layer. As a result, patients inevitably ended up with skin grafts and more difficult post-operative recovery. In 1988, after a series of long-term randomized trials clearly indicating that narrow, 1-2cm margins do not adversely affect recurrence rate or prognosis of disease, the WHO published new, simplified surgical guidelines, recommending 1-2cm margins depending on the thickness of the primary lesion.

For intermediate melanomas from 1.1-4mm thick, a sentinel lymph node biopsy is required. If the LN is positive, the surgeon proceeds with complete lymph node dissection. Complete dissection (minimum 15 lymph nodes) is always required for lesions >4mm, as the risk for metastasis is too great.

Radiation

Radiation is often used after surgical resection for patients with locally or regionally advanced melanoma or for patients with unresectable distant metastases. It may reduce the rate of local recurrence but does not prolong survival, as melanomas are resistant to its effects. It does play an important role, however, in a palliative setting, for localized control of metastatic lesions.

Systemic Therapy

The high rate of recurrence (45%-70%) in patients with node positive disease has been the motivation for multiple trials of various adjuvant therapies, none of which have yielded convincing evidence of benefit. Earlier therapies with interferon alpha showed benefit in disease-free survival, but had no overall survival benefit. A recent large, randomized study showed only a 7% response rate with 2 months to progression and no survival benefit for dacarbazine and temozolomide. In early studies, paclitaxel+carboplatin+sorafenib had encouraging response rate and time to progression; however, follow-up data showed minimal change due to the use of chemotherapy alone. Interleukin-2 was previously used as a low-dose subcutaneous injection, but showed no efficacy. It is now given as a high-dose IV bolus in ICU due to its extreme toxicity, with side effects such as capillary leak syndrome, hypotension, renal failure and hypoxia. Other therapies include inter-lesional local injection of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine or tamoxifen, with limited beneficial results.

In summary, for Stage I disease, the recommendation is to proceed with wide excision only. Stages II-III have various options, ranging from adjuvant chemotherapy to radiation to immune modulating therapies to clinical trials. Many complex contributing factors have to be taken into account when selecting appropriate treatment options. For stage IV disease, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend clinical trials due to the low response rates with other therapies.

Future Directions

As with many malignancies, the question of appropriate immune surveillances and immune patency of the host is often explored with malignant melanomas.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4) mediates an inhibitory effect on T-cell activation and function. Ipilimumab, a fully human anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody has been shown to enhance T-cell response and induce durable clinical effects with stabilization of disease. Larger, well-controlled, randomized studies are on the way to determine further efficacy of this antibody.

Studies evaluating M-Vax, an autologous hapten-modified human melanoma vaccine, given in conjunction with BCG vaccine, are now in process. Immunological competency of the host remains the primary challenge for obtaining vaccine efficacy, as it is the key in eliciting a response.

As we know, there are natural therapeutics that elicit an immune-enhancing effect in the body. The research is rather preliminary but does indicate that melatonin, for instance, has a direct inhibitory effect on melanoma, along with enhancing cell-mediated immune responses and cytokine modulation. Botanicals such as Astragalus membranaceus, Echinacea spp., Coriolus versicolor, Grifola frondosa, Viscum spp. and others warrant careful research and evaluation of their immunomodulatory effects in this patient population.

Prevention

The single most important factor in decreasing skin cancer incidence is prevention of UV radiation damage. Young adults have only moderate awareness about skin cancer and are unaware of sunburn being one of the major risk factors. Multiple programs have been implemented to raise awareness and educate healthcare practitioners, parents and children. Some recommendations include avoidance of midday sun, wearing protective clothing and eyewear, proper use of sunscreen, and knowledge of UV index information. Salon tanning should be discouraged, as it has been linked to development of melanomas.

Until recently, the role of sunscreen in preventing skin cancer has been debated among experts. Several large-scale, randomized studies showed that consistent use of sunscreen decreases the formation of actinic keratosis and subsequently reduces the occurrence of SCC and BCC. Unfortunately, the results have been discouraging for prevention of melanoma. This may be due to the fact that fair-skinned individuals who use sunscreen are at a higher risk for development of melanoma to begin with and/or that sunscreen use could give a false sense of security and encourage longer stays in the sun without complete protection.

The Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians (OncANP) was founded in 2004 to enhance the quality of life of people living with cancer through both increasing the collaboration between NDs working with patients with cancer and integrating naturopathic practice into medical oncology care. With its co-organization, the American Board of Naturopathic Oncology (ABNO), the OncANP has set standards, instituted testing and now credentials Fellows in Naturopathic Oncology. The OncANP welcomes all NDs interested in improving their knowledge and ability to work with oncology patients. For more information see www.OncANP.org.

Lidia Wiersum, ND graduated from NCNM in 2003 and subsequently completed a two-year residency specializing in oncology. She continues to practice as a naturopathic physician at Cancer Treatment Centers of America in Zion.

References

Alschuler LA: Definitive Guide to Cancer (2nd ed). Berkley, 2007, Celestial Arts.

American Cancer Society: www.cancer.org

Casciato DA, Lowitz BB: Manual of Clinical Oncology (4th ed). Philadelphia, 2000, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

Dermatology Information System: Dermatology Online Atlas, available at: http://dermis.multimedica.de/dermisroot/en/list/b/search.htm

DeVita VT et al: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology (6th ed). Philadelphia, 2001, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Edgar Staren, MD: Review of Skin Malignancies – Clinical Care Conference 2008, MRMC-CTCA

Fischer TW et al: Oncostatic effectgs of the indole melatonin and expression of its cytosolic and nuclear receptors in cultured human melanoma cell lines. Int J Oncol Sep;29(3):665-72, 2006.

Holland FJ, Frei E: Cancer Medicine. Hamilton, 2006, BC Decker Inc.

Kadekaro AL et al: MT-1 melatonin receptor expression increases the antiproliferative effects of melatonin on S-91 murine melanoma cells, J Pineal Res Apr;36(3):204-11, 2004.

Kolodney MS: Skin cancer: tips on prevention, clues to detection. Available at: www.consultantlive.com/display/article/10162/37164?pageNumber=2

Larsen HR: Sunscreens and cancer. Available at www.yourhealthbase.com/database/rsunscreens.htm

National Cancer Institute: www.cancer.gov

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Practice Guidelines in Oncology: www.nccn.org

Naylor MF et al: The Electronic Book of Dermatology. Available at: http://telemedicine.org/stamford.htm

Regodon S et al: Melatonin enhances the immune response to vaccination against A1 and C strains of Dichelobacter nodosus, Vaccine Jan 20, 2009.

Wood ME: Hematology/Oncology Secrets (2nd ed). Philadelphia, 1999, Hanley & Belfus Inc.

Yuan J et al: CTLA-4 blockade enhances polyfunctional NY-ESO-1 specific T cell responses in metastatic melanoma patients with clinical benefit, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA Dec 23;105(51):20410-5, 2008.