Dietary Fat and Chronic Pain: Balancing Omega-6 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids is Key

Keri Marshall, MS, ND

Pain, quite simply, is one of the most irritating of all symptoms for a patient. Chronic pain sufferers will often find themselves depressed, anxious, fatigued and lacking sleep as secondary complications of persistent pain. Each of the above symptoms will inevitably affect personal relationships, jobs and the ability to perform daily life activities.

As NDs, we often struggle to find the perfect balance between offering advice to change diet and lifestyle vs. using nutritional supplements to alter internal biochemistry. In many cases, patients are reluctant to change their diet and are in search of the “magic pill” that will cure what ails them.

When it comes to pain management, dietary fat has a direct relationship to how much pain and inflammation occur within the body. National dietary surveys have established a clear pattern in the Western diet – the overconsumption of omega-6 oils, with a relative deficiency of omega-3 fats. Scientists worldwide have come to the consensus that an imbalanced intake of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids promotes unnecessary inflammation and contributes to pain and chronic disease.

Undoubtedly, a major underlying factor in chronic pain is inflammation. Inflammation, in and of itself, is not all bad. In fact, inflammation is part of a healthy immune response, and is essential for battling germs and healing wounds. The all too familiar redness, heat and swelling that comes from an acute injury or trauma, such as a twisted ankle, is a sign of the inflammatory process at work.

It is when the inflammation fails to resolve after an infection or injury that it becomes a problem. Prolonged inflammation damages tissues, raises awareness to pain, disrupts metabolism and wreaks general havoc on most biological systems. Chronic inflammation and chronic pain syndromes are like peanut butter and jelly – always together. In addition, persistent low-grade inflammation has been implicated as a causative factor in a host of chronic disease states, including cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease and cancer.

Biochemistry of Inflammation

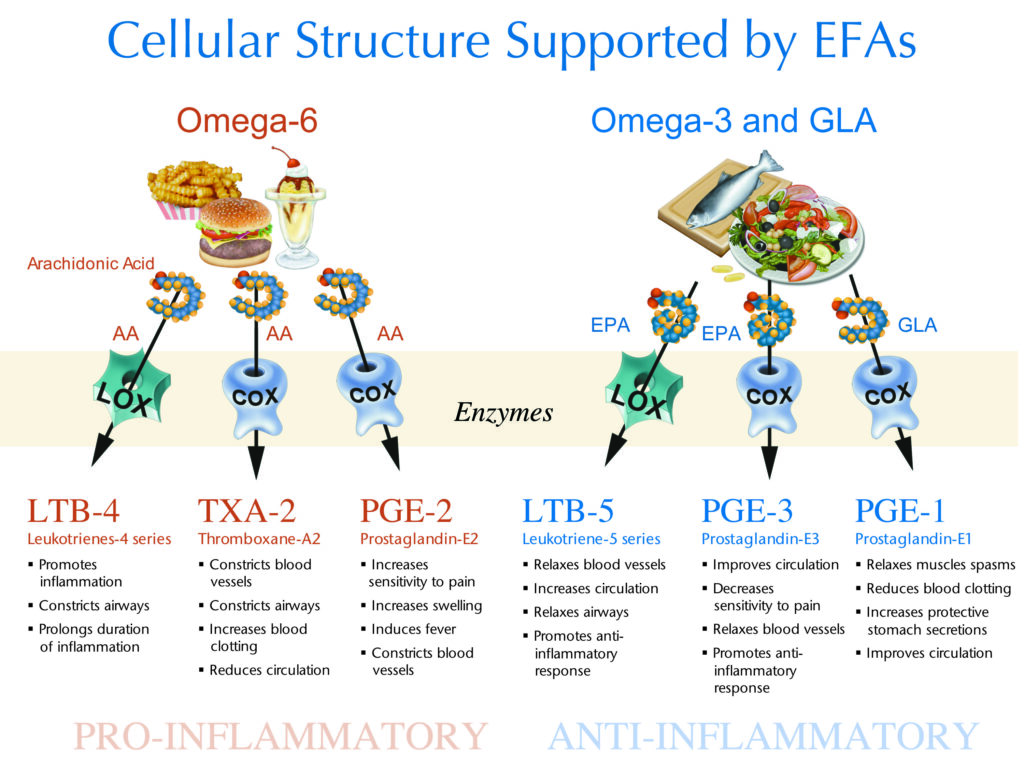

Eicosanoids (eicosa, Greek for 20) are signaling molecules derived from the 20 carbon omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Collectively, eicosanoids exert complex control over many bodily systems, particularly in inflammation and immunity, and as messengers in the central nervous system.

When the immune system is challenged by injury, infection, allergens or stress, fatty acids are released from cell membranes and converted by enzymes such as cyclooxygenase (COX) into eicosanoids. Attempts to interrupt this mechanism alone support the multi-billion-dollar industry of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and COX-2 inhibitors. If you can successfully block the conversion of fatty acids into eicosanoids, you can block inflammation caused by that eicosanoid.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a prominent eicosanoid derived from the omega-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA). A dominant action of PGE2 as a messenger molecule is to increase sensitivity in pain neurons. Higher levels of PGE2 are a necessary survival response.

Imagine a fractured humerus. The injury stimulates fatty acids to be released. AA is converted into PGE2, which increases pain and reminds us not to use the arm until it heals. Elevated PGE2 is not so helpful when the patient is sitting at a desk trying to meet a deadline, and is disrupted by chronic pain.

Overconsumption of omega-6 oils provides excess substrate for the synthesis of PGE2, which drives an aggressive and sustained inflammatory response. Chronic underlying inflammation results in chronic unrelenting pain.

Prostaglandin E3 (PGE3) is derived from the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Higher levels of PGE3 reduce sensitivity to pain, relax blood vessels, increase blood flow and support the body’s natural anti-inflammatory response.

It is important to remember that both PGE2 and PGE3 are necessary. It is the relative amounts of these competing messenger molecules that will either contribute to or mitigate chronic pain and inflammatory syndromes. EPA competes with AA for binding to the COX enzyme. The more EPA present, the less AA that can be converted into PGE2; thus, less inflammation and sensitivity to pain.

Balancing AA:EPA through supplementation with fish oil and the simultaneous reduction of dietary omega-6 fatty acid intake is a powerful way to reduce pain and inflammation. Conventional physicians of many disciplines are beginning to realize the value of balancing the omega-6 and omega-3 eicosanoids to modify inflammation. Blocking inflammatory pathways in this manner has recently been positioned as a much safer alternative to inhibiting the COX enzymes with drugs such as rofecoxib, celecoxib and valdecoxib.

Diet and Lifestyle

The balance between the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory eicosanoids is influenced in large part by the type of fatty acids consumed in our daily diet. The primary sources of omega-6 oils in our diet are vegetable oils, such as corn, soy, safflower and sunflower.

Before the turn of the century, no significant sources of omega-6 vegetable oils existed in our diet. Most cultures consumed diets low in these oils and high in fish, creating a ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 that was roughly 3:1.

The industrial revolution brought with it the knowledge and tools to refine vegetable oils, which resulted in a rapid shift of dietary habits for most Western cultures. Omega-6:omega-3 was quickly pushed toward the current estimate of 20:1. The human body has not been able to genetically adapt to this dramatic shift in fatty acid consumption.

Today, most modern cultures consume copious vegetable oils (mostly in processed foods). For example, soy oil production for food consumption increased 1,000-fold between 1909 and 1999. In addition, livestock, poultry and farmed fish are being fed cornmeal and soy-based feed, which raises the omega-6 content of this meat. When farm animals are raised on grass, worms or other natural diets, the tissues are naturally higher in omega-3 fatty acids.

One example of this is the beef industry, with bragging rights to a “marbling effect” in finished beef products. Cattle that are fed corn and soy will have a higher omega-6 content compared to grass-fed cattle. Grass-fed cattle can contain up to 4% omega-3 fatty acids, while corn-fed cattle typically contain 0.5% (O’Sullivan et al., 2002). Similarly, two eggs from free-range hens can contain up to 700mg omega-3 fats, with an omega-6:omega-3 of 2:1.

The Standard American Diet (SAD) supplies an average omega-6:omega-3 of 11:1. Patients with inflammatory and neurological conditions will often present with 20:1. Vegetarians are also at risk for eating high amounts of vegetable oils and soy products, which can tip the balance toward inflammation.

Labs now offer Fatty Acid Analysis, which provides an objective measure of fatty acids in the blood. Measuring a patient’s AA:EPA can provide a snapshot into the biochemistry underlying the inflammatory process. This measurement can also help monitor patients on long-term, high dose omega-3 supplementation.

Reducing dietary vegetable oils and increasing the omega-3 fats EPA is imperative for patients experiencing chronic pain. It is also recommended to increase the intake of DHA, as this omega-3 essential fatty also contributes to inflammation modulation. Some practitioners still recommend flax and walnuts as an efficient way to obtain EPA and DHA. Flax is a source of the omega-3 fatty acid alpha-linolenic acid, which does not readily convert to EPA. Research has shown that alpha-linolenic acid supplementation is not as effective at modifying inflammation as preformed EPA from fish oil. Only approximately 10% of alpha-linolenic acid is converted to EPA, and flax meal or flax oil supplementation has a minimal effect on eicosanoid production and blocking the production of PGE2.

Fish Oil

Research has shown that supplementation with fish oil is a safe and effective way to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory and pain-sensitizing messenger molecules while simultaneously raising the levels of anti-inflammatory, self-healing molecules. Many clinical trials show great promise in reducing overall pain and inflammation in several chronic disease states, including arthritis and discogenic disease.

At the time the rofecoxib scandal was unfolding, many well-meaning physicians became aware they were putting patients at unacceptable risks. One such physician, Dr. Joe Maroon, a neurosurgeon from Pittsburgh, decided to put fish oil to the test in his chronic pain patients who were currently using drugs to manage their pain. Dr. Maroon conducted a study, published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, on 250 patients with non-surgical back or neck pain (Maroon and Bost, 2006). Patients took 2,400mg (EPA + DHA) daily for two weeks, then 1,200mg daily thereafter. All patients were initially using NSAIDs, with 75% of them on COX-2 inhibitors. Of those patients who responded to a survey three months later:

- 59% reported being able to discontinue taking NSAID medication

- 60% reported overall pain relief that was not achieved using NSAIDS alone

- 60% reported that joint pain had improved

- 80% were satisfied with their improvement

- 88% said they would continue to take their fish oil supplement.

Clinically, reducing inflammation in most patients requires 3g total of EPA + DHA daily (this is not equal to total grams of oil in the capsule). This dose varies depending on the background intake of omega-6 vegetable oils, but is considered a mid-range anti-inflammatory dose.

As a reminder, fish oils come in a variety of EPA + DHA concentrations. For example, cod liver oil liquid has approximately 1g EPA + DHA per teaspoon, and a 3g dose can be achieved in a tablespoon. For patients preferring capsules, regular-strength fish body oil is about 300mg EPA + DHA per cap, requiring about 10 caps daily for an anti-inflammatory dose. Most patients prefer a concentrated fish oil product, which can provide a 3g dose in as little as five caps.

There is an additional consideration when choosing concentrated fish oil products: Most practitioners are unaware that concentrated fish oil products are available in two distinctly unique molecular packages – the synthetic ethyl ester form or natural triglyceride form. There is much debate surrounding these two molecular packages of EPA and DHA among fish oil enthusiasts. Since there have been no firm conclusions to this debate, I encourage practitioners to educate themselves about the issues that surround ethyl esters vs. triglycerides and make an informed decision for patients.

Keri Marshall, ND practices in New Hampshire, and specializes in pediatrics and women’s medicine. She has published several scientific papers and magazine articles, and wrote a book on proteins and amino acids. Dr. Marshall serves as the scientific advisor to Citizens for Health, a national non-profit consumer advocacy group working to broaden healthcare options and advance the freedom to make health choices. Devoted to children’s health and wellness, Dr. Marshall also serves as a nutrition expert on the Wellness Committee in the Oyster River School District, helping to change the district’s lunch program by integrating healthier options. She is also a part of the advisory panel for Nordic Naturals. Dr. Marshall received her naturopathic medical degree from NCNM.

References

Adam O et al: Anti-inflammatory effects of a low arachidonic acid diet and fish oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Rheumatol Int 23:27-36, 2003.

Calder PC: n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases, Am J Clin Nutr 83:S1505-1519, 2006.

Cleland LG and James MJ: Fish oil and rheumatoid arthritis: antiinflammatory and collateral health benefits, J Rheumatol 27:2305-7, 2000.

MacLean CH et al: Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, renal disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and osteoporosis (Evidence report/technical assessment no. 89; AHRQ publication no. 04-E012-2), Rockville, 2004, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Maroon JC and Bost JW: Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain, Surg Neurol 65:326-331, 2006.

Mukherjee PK et al: Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8491-6, 2004.

O’Sullivan A et al: Grass silage versus maize silage effects on retail packaged beef quality, J Anim Sci Jun;80(6):1556-63, 2002.

Yaqoob P: Fatty acids as gatekeepers of immune cell regulation, Trends Immunol 24:639-45, 2003.