Herbal High Road Can Alleviate Pain Precisely: Formulas for Acutely Painful Conditions Aimed at Restoring and Correcting Underlying Pathology

Jillian Stansbury, ND

Pain is of course a good way to get our attention that something is wrong in the body. We can ignore less urgent symptoms for months and even years on end, but not pain. Treatment of patients with painful conditions and acute pain often has several goals. We expect to offer something that will assuage pain as completely and rapidly as is possible, while simultaneously aiming not only to treat the pain but also to begin addressing the underlying factors that have created it. Having taught botanical medicine at naturopathic schools for more than 20 years, I have been witness on multiple occasions to students’ concerns about palliating pain. “Isn’t this suppression?” they ask. “Isn’t pain an appropriate manifestation of the underlying pathology?” “If you give pain relievers, can you still determine what more comprehensive treatment protocols are accomplishing?” These are all good questions and ones with the core philosophical tenets of naturopathic medicine at heart.

First of all, botanical pain relievers are not usually suppressive, although they can be; colchicine for the inflammatory pain of acute gout is a good example. Colchicine halts white blood cell phagocytosis of uric acid crystals; so, yes, we could say it suppresses an appropriate action of the body’s immune wisdom. Some botanical pain relievers are palliative rather than suppressive, helping to relieve pain but neither suppressing it nor really treating it. Applying capsaicin ointments on sore joints and muscles is a good example here. Capsaicin promotes the release of substance P from pain fibers, creating a warm to hot sensation that masks pain and does not suppress it, but neither does it relax a muscle spasm or repair a degenerated disk or arthritic joint. Because it is impossible to rebuild a degenerated joint by bedtime, we seek palliatives to help patients sleep better right away, while simultaneously working on the slower process of connective tissue rejuvenation. Effective herbal palliatives that at least “do no harm”—as do so many pharmaceutical corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anodynes—are extremely valuable medicines.

And then there is the herbal high road. There are some instances where herbal therapy might alleviate pain precisely because it is treating and correcting the underlying pathology that is the cause of the pain. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is difficult to remedy with suppressive or palliative anodynes, but agents that enhance circulation and perfusion to distal nerves may help the symptom of pain and the underlying pathology creating it. Herbal antispasmodics, such as Passiflora and Valeriana, may relax a muscle and treat the underlying mental stress that caused it. Piper methysticum (kava) may allay the pain of renal colic, relax the ureter, and help a stone to pass, while morphine may only numb the pain and in fact allow a renal stone to lodge all the tighter as the spastic ureter becomes more inflamed and edematous. Matricaria (chamomile) and Glycyrrhiza (licorice) may allay gastric pain, while helping to heal ulcerative lesions and rebuild the mucous membrane integrity, which is the underlying cause of the pathology and pain in the first place.

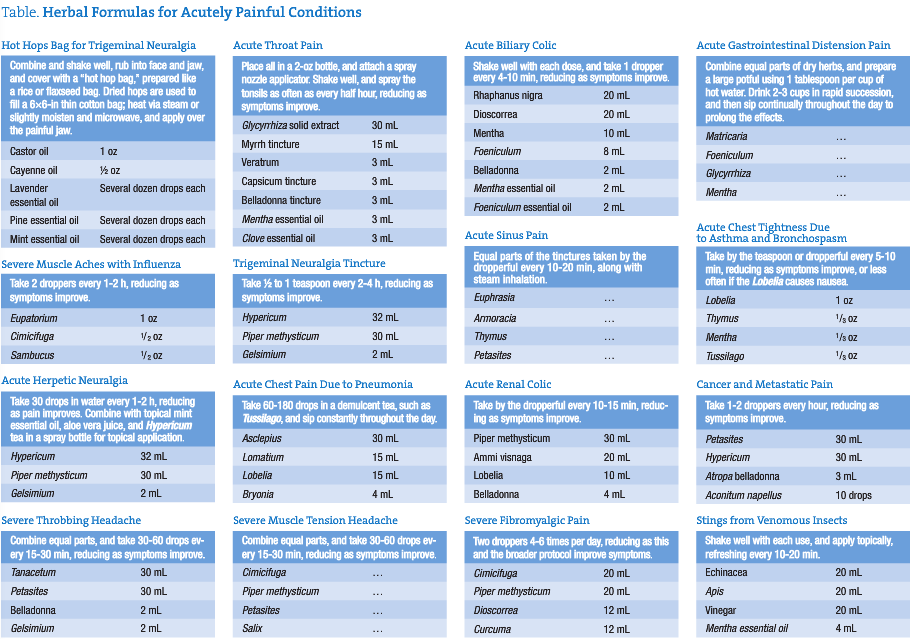

I have sat down and thought through the most common acute pain situations and conditions I have seen in clinical practice. The Table contains a short list of herbal formulas for acutely painful conditions that I do not believe to be suppressive, are at least palliative, and are aimed even higher at restoring and correcting the underlying pathology. These are formulas for acute pain relief and are not intended to be the sole approach to any given case or situation. Many of these formulas contain low-dose prescription-only botanicals, such as Conium, belladonna, Gelsimium, Aconitum, and Bryonia, which are intended for administration by experienced and licensed clinicians only and may simply be omitted from the formulas for those without adequate familiarity and comfort. These botanicals were typically used by the Eclectic physicians in something akin to homeopathic dosage, where just 1 to 20 drops were placed in a 4-oz bottle and then taken by the teaspoon.

Aconite is the most powerful and potentially harmful of the botanicals used in these formulas. One of my formulas uses 10 drops in a 2-oz bottle of tincture, which is significantly more than the highly diluted Eclectic formulas but within a safe dosage range. The toxicity symptoms of Aconitum are numbness and tingling, and all further use should be discontinued at that point. Bryonia can be taken in doses of 5 to 10 drops at a time and is specifically indicated for pain that is sharp and cutting and is worse in motion. The addition of a few milliliters per ounce of other herbs in a formula will deliver no more than the 5 drops at any one dose. Similarly, belladonna can be taken at a dose of 5 drops at a time, and 2 to 5 mL can be included in a 2-oz formula. Belladonna is specifically indicated for spastic pain, such as renal or biliary colic, intestinal spasm, and spasm of skeletal muscles. Dilated pupils and a flushed face are toxicity symptoms of belladonna. Conium is a peripheral motor nerve suppressant that is most specific for neuralgic pain and can be safely dosed at 1 to 3 drops at any one time; therefore, 1 or 2 mL may be used in a 2-oz tincture formula. Slowing of the pulse rate may be the first sign of toxicity, progressing to numbness and muscular incoordination with repeated dosing. Conium may allay pain of cancer, arthritic joints, and glandular swellings. Extreme restlessness and nervous agitation due to pain may also respond to Conium. Gelsimium is also a motor suppressant, particularly to the nerves of the head and face, and is specific for hyperemic and neuralgic situations, including a throbbing headache. Droopy eyelids, slurred speech, and diplopia are toxicity symptoms that result from excessive dimming of motor functions in the facial nerves.

Jillian Stansbury, ND has practiced in SW Washington for nearly 20 years, specializing in women’s health, mental health and chronic disease. She holds undergraduate degrees in medical illustration and medical assisting, and graduated with honors in both programs. Dr Stansbury also chaired the botanical medicine program at NCNM and has taught the core botanical curricula for more than 20 years. In addition, Dr Stansbury also writes and serves as a medical editor for numerous professional journals and lay publications, plus teaches natural products chemistry and herbal medicine around the country. At present she is working to set up a humanitarian service organization in Peru and studying South American ethnobotany. She is the mother of two adult children, and her hobbies include art, music, gardening, camping, international travel, and studying quantum and metaphysics.

Jillian Stansbury, ND has practiced in SW Washington for nearly 20 years, specializing in women’s health, mental health and chronic disease. She holds undergraduate degrees in medical illustration and medical assisting, and graduated with honors in both programs. Dr Stansbury also chaired the botanical medicine program at NCNM and has taught the core botanical curricula for more than 20 years. In addition, Dr Stansbury also writes and serves as a medical editor for numerous professional journals and lay publications, plus teaches natural products chemistry and herbal medicine around the country. At present she is working to set up a humanitarian service organization in Peru and studying South American ethnobotany. She is the mother of two adult children, and her hobbies include art, music, gardening, camping, international travel, and studying quantum and metaphysics.