Bradley Bush, ND

Exploring how neuroimmune imbalances between histamine and serotonin contribute to dysmotility, GERD, and bloating—and how targeted integrative strategies can improve outcomes.

Abstract

This article reviews the interplay between histamine and serotonin in upper GI motility and highlights three clinical cases. It provides practical insights into assessment, treatment strategies, and the importance of balancing neurotransmitter and immune function in Neuroimmune crosstalk between histamine and serotonin is a hidden driver of upper GI dysmotility, GERD, and bloating. These case reviews demonstrate how targeted testing and stepwise interventions (antihistamines, 5-HTP, mast-cell stabilization, nutrient repletion) can normalize motility and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction: A Hidden Tug-of-War in the Upper Gut

Upper GI motility disorders—dysphagia, bloating, belching, and early satiety—are often frustrating for both patients and practitioners. While diagnoses like SIBO or GERD are commonly assigned, a deeper layer of neuroimmune imbalance is often overlooked: the interaction between histamine and serotonin signaling.

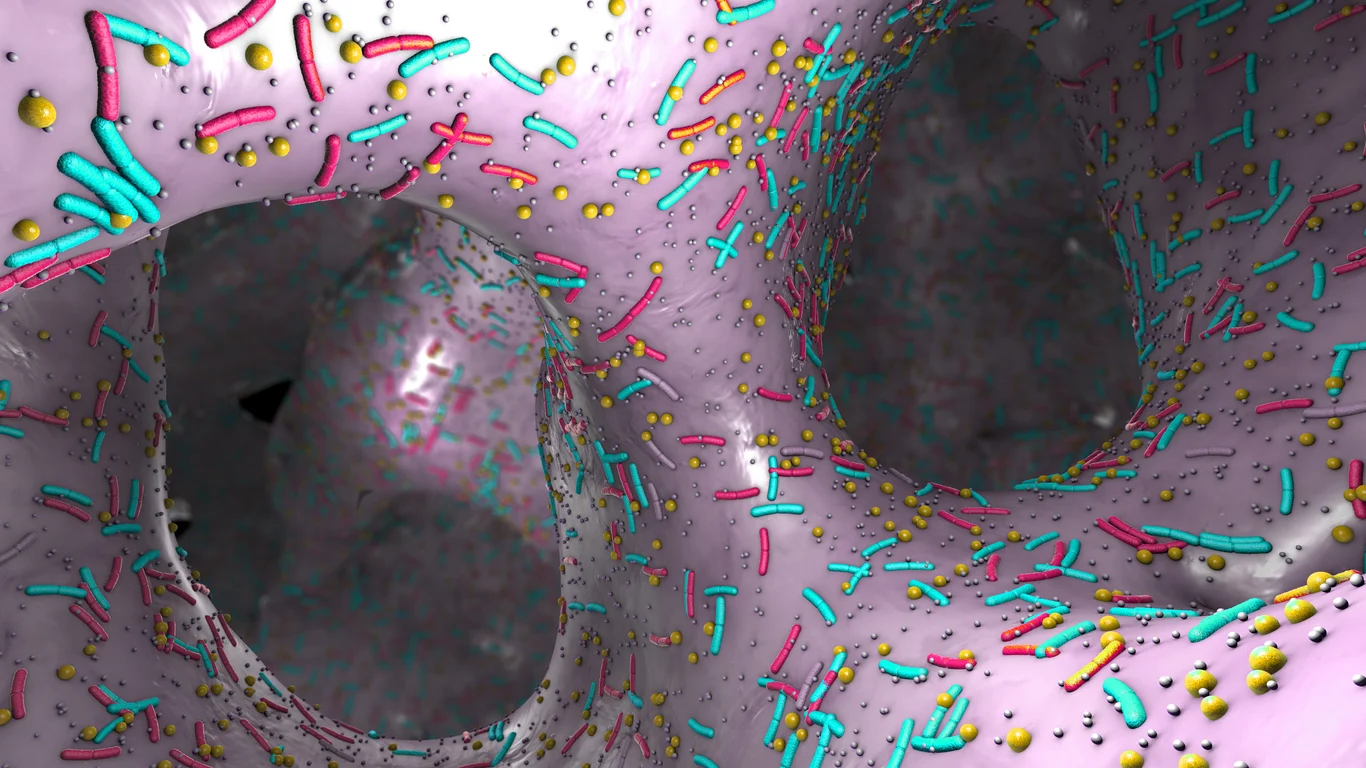

Histamine, known for its inflammatory and allergic roles, also stimulates gastric acid and gut muscle contraction. Serotonin (5-HT), primarily produced in the gut, helps regulate peristalsis and the enteric nervous system.1-3 When histamine is elevated and serotonin is deficient, the result can be erratic or stalled motility, often manifesting as a wide range of upper GI symptoms.

About 90–95% of the body’s serotonin is produced and stored in the gut, primarily by enterochromaffin (EC) cells in the intestinal mucosa. Serotonin plays a prokinetic (movement-promoting) role in the GI tract and is essential for coordinating peristalsis, secretion, and visceral sensation.2,3

5-HT binds to 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors on intrinsic primary afferent neurons (IPANs) within the enteric nervous system. 2,3 HT3 receptors are ligand-gated ion channels initiating fast excitatory neurotransmission, while 5-HT4 receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors that promote acetylcholine release to enhance peristalsis.

Serotonin is normally released in response to luminal distention which activates peristaltic reflex arcs, triggering muscle contraction above and relaxation below the food bolus, facilitating forward propulsion of contents.1-3 Serotonin synthesis requires L-tryptophan, converted by tryptophan hydroxylase and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC). Vitamin B6, folate, and B12 are essential cofactors; deficiencies can lead to hypomotility. MTHFR gene mutations can reduce serotonin production.

Histamine is produced primarily by mast cells, enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, and neurons in the gut with basophils being moderate contributors, especially with allergy responses. It affects gastric acid secretion, smooth muscle tone, and inflammatory signaling. H1 receptors mediate smooth muscle contraction and neural activation; H2 receptors stimulate acid secretion and influence muscle tone.4,5 H3 and H4 receptors modulate immune-neural crosstalk.

Allergens, infections/ overgrowths (including SIBO and SIFO), and stress can trigger mast cell degranulation, releasing histamine. This promotes intestinal permeability, cytokine release, and smooth muscle contraction—contributing to spasms and bloating.5 This is why many patients present with histamine overload symptoms, including: anxiety, insomnia, skin itching, headaches, flushing, hives, itching, nasal congestion, diarrhea, bloating, and even more severe reactions like asthma attacks or rapid heart rate.

Histamine can relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), worsening GERD and dysphagia.6 In the stomach, it stimulates acid secretion and influences motility patterns. Histamine from mucosal mast cells stimulates enteric neurons, increasing both sensory perception and motor responses. This may lead to diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain.

Summary of Effects on GI Motility

| Neurochemical | Primary Receptors | Action on Gut Motility | Clinical Effects When Imbalanced |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | 5-HT3, 5-HT4 | Stimulates ENS, promotes peristalsis | Constipation, bloating, and delayed gastric emptying |

| Histamine | H1 (contraction), H2 (acid & tone) | Modulates tone, acid secretion, and inflammation | Spasms, bloating, GERD, visceral pain |

Mechanisms of Dysregulation

Several physiological and environmental factors may predispose to gut motility disorder:

- Genetic SNPs (e.g., MTHFR) impair folate-dependent neurotransmitter synthesis.

- B12 malabsorption leads to reduced methylation and serotonin synthesis.

- Food and environmental allergies activate mast cells and histamine release.

- Post-infectious syndromes (e.g., COVID or food poisoning) can damage enteric neurons or alter immune tolerance.

- SIBO and GERD contribute to chronic inflammation and neuromuscular dysfunction.

Initial Clinical Workup and Protocol

Patients presenting with upper GI symptoms and suspected neuroimmune involvement are typically assessed with:

- Lactulose breath test to evaluate SIBO and transit patterns

- Comprehensive blood work: B12, folate, homocysteine, CBC w/ diff. CMP, vitamin D, hs-CRP, IgE, HbA1c, Lp(a), insulin

- Targeted food sensitivity panels (IgE, IgG, IgG4, C3a)

Initial treatment approach includes:

- H1 blocker: Cetirizine 10 mg BID

- H2 blocker: Famotidine 20 mg BID

- 5-HTP SR: 200 mg AM, 150 mg PM (avoided or reduced with SLC6A4 down-regulated gene mutations)

- Supportive nutrients: Quercetin 500-1000mg BID, bioflavonoids 150-500mg BID, and L-glutamine (5g BID).

Treatment is then phased:

- Phase I – Reduce histamine, increase serotonin

- Phase II – Correct nutrient and inflammatory lab abnormalities

- Phase III – Introduce prescriptive mast cell stabilizer and/or serotonin/ histamine support (e.g., Cromolyn sodium, mirtazapine)

Case 1: Adolescent Onset Post-Stress

Patient: 16-year-old female

Symptoms: Belching, bloating, dysphagia, insomnia, anxiety

Findings: Elevated total IgE, mildly high hs-CRP, low-normal B12, elevated MCV

SIBO: Negative but with atypical hydrogen pattern

Treatment Summary:

She responded quickly to antihistamines, quercetin, and L-glutamine. Added sublingual methyl-B12, Dust mite reduction improved baseline inflammation. Symptoms improved >75% within 2 months. She continued taking 150 mg SR 5-HTP at night and was referred for sublingual immunotherapy after food/environmental allergy testing.

Case 2: Chronic Panic and Constipation

Patient: 32-year-old male

Symptoms: IBS-C since his teenage years, bloating, panic attacks (worse the last 6 months), acne, moderate depression

History: Chronic childhood infections, strep, ear tubes

Genetics: MTHFR C677T homozygous mutation

SIBO: Positive hydrogen and methane

Labs: Egg allergy (IgE, IgG, and CA3), normal B12, elevated homocysteine (12)

Treatment Summary:

5-MTHF titrated to 12 mg daily, egg-free SIBO-specific diet initiated. SIBO was treated with allicin, oregano, and berberine BID for 4 weeks. Bowel movements normalized, panic attacks resolved, and mood dramatically improved.

Case 3: Severe Bloating and GERD with Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Patient: 46-year-old female

Symptoms: Severe belching, bloating, dysphagia, GERD, eosinophilic esophagitis

Allergies: Daisy family (self-reported): instructed to remove cross-reactive foods.

Labs: Elevated eosinophils, hs-CRP, homocysteine; low-normal iron; high-normal MCV

SIBO: Negative, but hydrogen remained elevated throughout

Treatment Summary:

Initial relief was mild. Adding B12, a B-complex, and Cromolyn sodium (titrated olive oil base) significantly improved anxiety, dysphagia, and throat pain. After initiating mirtazapine (started at 7.5mg (½ tab) and increased to 15mg (1 tab) after 1 week), belching and bloating ceased, and dysphagia further improved. Mirtazapine was tapered off after one month. Oral BPC-157 (500 mg nightly) improved residual dysphagia and inflammation, with follow-up endoscopy showing approximately 75% healing.

Note: Cromolyn sodium 100mg/ ml compounded into olive oil and titrated slowly, starting with 1/4ml (25mg) once daily before eating, increasing by 1/4ml (25mg) every 3 days until she reached 1/2ml (50mg) four times daily. I prefer using compounded Cromolyn sodium to initiate treatment due to the easier ability to titrate with less wasted medicine (commercial Cromolyn sodium only comes in ampules and is not very user-friendly for patients). Cromolyn sodium is primarily known as a mast cell stabilizer, but evidence (research and clinical) also supports its ability to inhibit activation of eosinophils and basophils, making it a broader immune modulator in allergic and eosinophilic conditions.7 If cromolyn sodium is not beneficial within 2 weeks, I will switch to or add oral ketotifen.

Clinical Pearls and Closing Thoughts

- Histamine and serotonin imbalances can mimic or worsen SIBO-like symptoms. Always consider neuroimmune dynamics when SIBO tests are atypical or negative.

- High daytime serotonin (5-HTP) dosing may be required due to diurnal competition with dopamine via AADC.

- Mirtazapine, though sedating, can be useful short-term for vagal restoration and upper GI motor normalization due to its antagonism at H1, 5-HT2, and 5-HT3 receptors.

- Individuals with daisy family allergies, especially those with oral allergy syndrome (OAS) or pollen food allergy syndrome (PFAS)—may experience cross-reactivity with several foods. These include lettuce, chicory, endive, globe and Jerusalem artichokes, sunflower (both seeds and pollen, particularly in relation to mugwort cross-reactivity), safflower, chamomile (including teas), echinacea, and dandelion.While daisy allergies are less common than pollen allergies such as birch, they can still play a significant role in triggering OAS or PFAS symptoms and should be considered in patients with persistent GI or allergic complaints.

- Environmental and food allergies may play an outsized role in chronic upper GI dysfunction via mast cell activation and eosinophilic inflammation.

These cases emphasize that successful treatment of upper GI motility issues often requires balancing neurotransmitter tone, reducing immune activation, and correcting root-level biochemical imbalances. Patient often present with classic GI symptoms associated with SIBO, but lab results are either negative or atypical. Irregular serotonin and histamine activity are not only common side effects of chronic GI issues but can be a root cause for irregular gut motility and resulting bacterial imbalances. This case study review is being shared to shine a light on a neuro-immune cause for many symptoms often blamed on gut flora imbalances or parasites. Consider using this approach in those more challenging cases especially when patient history or reactions to past treatments suggests that there may be more than one mechanism impacting gut motility and the patient’s overall health and wellness.

Bradley Bush, ND, is a naturopathic doctor who graduated from NCNM (now National University of Naturopathic Medicine) in Portland, OR. He is the owner and Clinic Director of Natural Medicine of Stillwater and the breath testing lab Neurovanna, both based in Stillwater, MN and Chief Medical Officer for the Endurance Products Company. Dr. Bush specializes in gastrointestinal health, mood disorders, neuro-endocrine conditions, insomnia, infections, and autoimmune diseases. Residing in Stillwater with his naturopathic doctor wife and four daughters, he enjoys cooking and gardening in his free time.

References

- Wood JD. Enteric nervous system: reflexes, pattern generators and motility. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;24(2):149-58. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f56125. PMID: 18301264.

- Mawe GM, Hoffman JM. Serotonin signalling in the gut–functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Aug;10(8):473-86. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.105. Epub 2013 Jun 25. Erratum in: Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;10(10):564. PMID: 23797870; PMCID: PMC4048923.

- Gershon MD. Review article: serotonin receptors and transporters — roles in normal and abnormal gastrointestinal motility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Nov;20 Suppl 7:3-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02180.x. PMID: 15521849.

- Wouters MM, Vicario M, Santos J. The role of mast cells in functional GI disorders. Gut. 2016 Jan;65(1):155-68. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309151. Epub 2015 Jul 20. PMID: 26194403.

- Bischoff SC. Role of mast cells in allergic and non-allergic immune responses: comparison of human and murine data. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 Feb;7(2):93-104. doi: 10.1038/nri2018. PMID: 17259966.

- Liacouras CA, Ruchelli E. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004 Oct;16(5):560-6. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000141071.47572.eb. PMID: 15367851.

- Amayasu H, Nakabayashi M, Akahori K, Ishizaki Y, Shoji T, Nakagawa H, Hasegawa H, Yoshida S. Cromolyn sodium suppresses eosinophilic inflammation in patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001 Aug;87(2):146-50. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62210-7. PMID: 11527248.