Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP)

Regenerative Medicine

Fred G. Arnold, DC, NMD

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is the third topic in my series about regenerative medicine treatments for painful musculoskeletal conditions. This regenerative injection procedure was originally used in 1987 following open-heart surgery. Since that time, PRP has gained recognition as a popular procedure in a variety of medical fields, “including orthopedics, dentistry, ENT, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, urology, wound healing, as well as cosmetic, cardiothoracic and maxillofacial surgery.”1 PRP’s acceptance and popularity with the public is partly a result of professional athletes, such as the golfer, Tiger Woods, and several major league pitchers using the procedure.1

In the practice of orthopedics, “orthobiologics” is defined as substances that can facilitate the healing of cartilage, bone, muscle, tendon, and ligament.2 PRP is an autologous orthobiologic solution. “Autologous” simply refers to the fact the solution utilized in the procedure is taken from the patient.3

PRP is also marketed for its multiple therapeutic applications in the field of aesthetics, including wound healing, hair restoration,4 breast augmentation,5 facial rejuvenation,6 and treatment of both male7 and female8 sexual dysfunction. A common observation in these studies is the lack of standardized methods and documentation to support clinical outcomes.

PRP is even gaining acceptance in the veterinary world. In the June 2019 issue of Innovative Veterinary Care,9 the authors explain that “PRP stimulates the repair of soft tissues and joints … and uses the body’s own programming for self-healing on an amplified scale.”

How Does PRP Work?

PRP involves removing a precise amount of the patient’s own blood and concentrating the platelets, creating a supraphysiologic concentration of platelets that are then precisely injected to improve functioning, dependent upon the patient’s condition.

When an injury occurs in a blood vessel, platelets migrate to the site of damage and form a plug (clot). A normal platelet count is 150 000 to 450 000 platelets per microliter (µL) of blood, with an average baseline of 200 000 platelets/µL.10 Studies have demonstrated clinical benefits using a minimum of 4 times the200 000 platelet/µL baseline. This is considered the benchmark for “therapeutic PRP”; a count of 1 million/µL is the standard concentration.1

The benefits of PRP derive from the 3-5-fold concentrate of growth factors and cytokines. Growth factors and mediators promoting regeneration and healing include TGF-1, IGF-1, IGF-B, VEGF, PDGF, bFGF, and EGF. These growth factors play an important role in cell proliferation, chemotaxis, cell differentiation, and angiogenesis.11,12 The healing mechanism of PRP is the localized inflammatory response that triggers a wound-healing cascade. This results in the deposition of new collagen in tissues such as tendons and ligaments. The new collagen contracts as it matures, providing stability to the injection site and reduction of pain.11

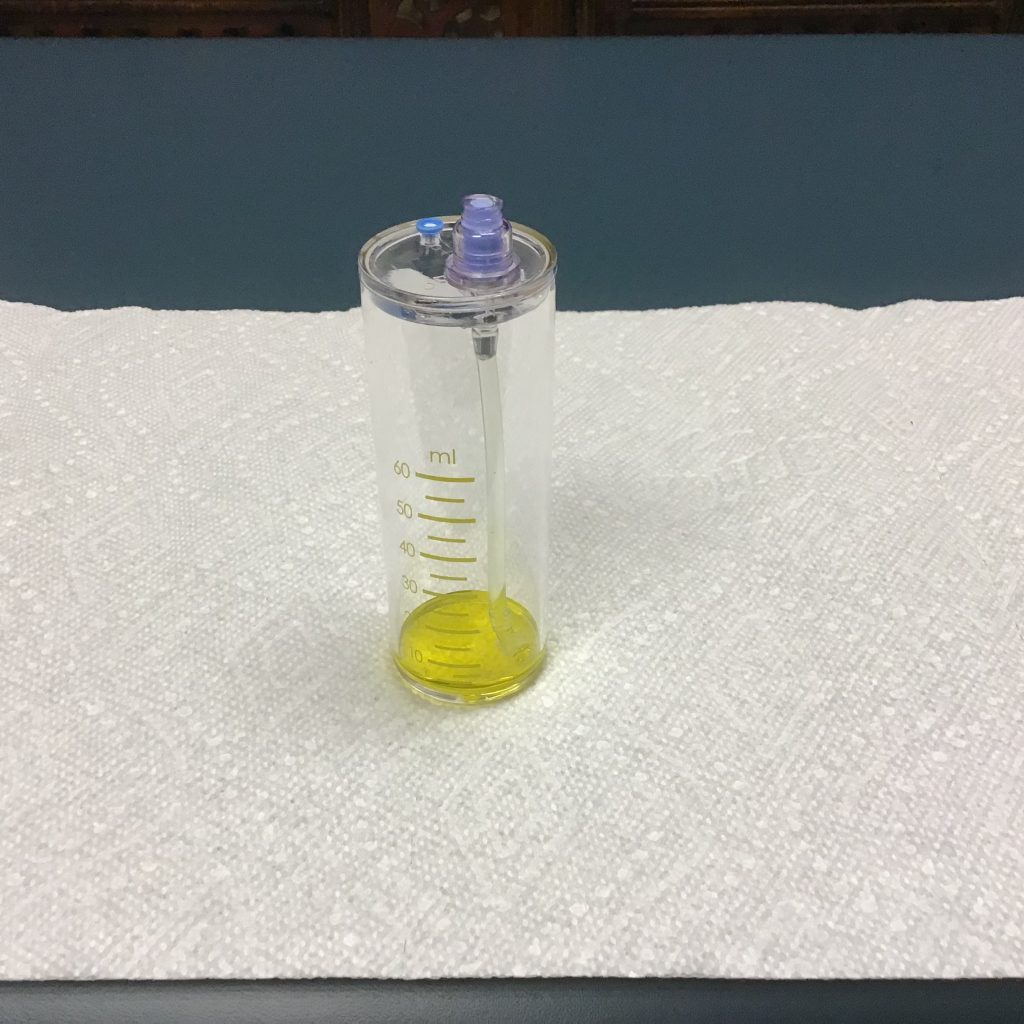

Figures 1a-d. Platelet Collection for Injection

Figure 1a

60 cc of blood from the patient are transferred to the concentrating container

Figure 1b

Serum is separated from the RBCs after the first centrifuge spin

Figure 1c

Platelet plasma after the second centrifuge spin, now in a different concentrating container

Figure 1d

5-10 cc of platelets are separated from the plasma for injection

There are many different PRP systems, each of which may utilize a different platelet yield concentration. Because there is no standardized PRP preparation, the practitioner should evaluate the collection method that best meets his or her practice needs.

Solutions & Applications Aren’t Created Equal

PRP Solutions

PRP solutions are influenced by the amount of blood taken, the final volume of plasma in which the platelets are suspended, the presence or absence of RBCs and WBCs, the presence or absence of anticoagulant in the sample, and the addition or absence of thrombin or calcium chloride.13

Lack of benefit observed in some studies can be traced to a variety of factors. Poor-quality PRP can be attributed to factors such as inadequate devices or subtherapeutic levels of platelets.11 As stated by Weibrich et al, “Advantageous biological effects seem to occur when PRP with a platelet concentration of approximately 1,000,000/microl is used. At lower concentrations, the effect is suboptimal, while higher concentrations might have a paradoxically inhibitory effect.”14

PRP solutions can be further differentiated by leukocyte-rich PRP vs leukocyte-poor PRP. As the terms suggest, leukocyte-rich PRP refers to a higher concentration of WBCs (neutrophils), whereas leukocyte-poor PRP refers to a lower concentration of WBCs, below baseline. Various research studies support the application of different solutions, dependent upon the area treated.12

PRP Applications

Dr Gary Clark and the Hackett-Hemwall-Patterson Foundation have discussed the importance of Clinical BioTensegrity in the treatment of painful musculoskeletal conditions.15 Following the principals of BioTensegrity with PRP when treating a painful knee, for example, multiple areas would be injected, including the intra-articular joint and extra-articular structures, such as the patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, medial collateral ligament, lateral collateral ligament, and pes anserine tendons.

There is consensus in the literature for a standard protocol for PRP preparation and application.16 Multiple investigators have concluded that further research is needed to properly assess the efficacy of PRP treatment to produce optimum benefit based on evidence-based guidelines.17-20 According to a recent Chinese study, “A large, multicenter, randomized trial is needed to further assess the efficacy of PRP treatment for patients with knee OA.”16 And the authors of a 2019 review recommend that future research focus on “the ideal type, dose, frequency of injection and mode of injection.”21

Table 1. Common Musculoskeletal Conditions Treated with PRP

| Achilles tear | Hip pain & arthritis | Rotator cuff tears |

| Achilles tendonitis | Joint laxity & instability | Rotator cuff tendonitis |

| Ankle pain & arthritis | Knee pain & arthritis | Sacroiliac joint pain |

| Ankle sprains | Knee ligament injuries | Sciatica |

| Cartilage damage | Knee tendonitis | Shoulder pain & arthritis |

| Cervical radiculitis | Ligament tear | Spinal disc problems |

| Elbow pain & arthritis | Low back pain | Sprains & strains |

| Elbow tendonitis | Neck pain | Tendonitis |

| Foot pain & arthritis | Patellar tendonitis | Thoracic pain |

| Golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis) | Pelvic pain | Tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) |

| Hand pain & arthritis | Plantar fasciitis | Wrist pain & arthritis |

PRP Studies

Varying outcomes are reported in the literature regarding the effectiveness of PRP for different conditions:

- Knee osteoarthritis: In a 2017 systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 1423 participants, the investigators concluded that intra-articular knee PRP injections “probably are more efficacious in the treatment of knee OA (osteoarthritis) in terms of pain relief and self-report function improvement at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up, compared with other injections, including saline placebo, HA, ozone, and corticosteroids.”22 Another systematic review found significant clinical improvements in knee osteoarthritis treated with PRP.23

- Tendinopathy: A 2016 meta-analysis, including 18 studies and 1066 participants, examined the effectiveness of PRP in treating tendinopathy, with the primary outcome measure being change in pain intensity.24 The authors concluded, “There is good evidence to support the use of leukocyte-rich PRP under ultrasound guidance in tendinopathy. Both the preparation and intratendinous injection technique of PRP appear to be of great clinical significance.”

- Musculoskeletal injuries: A 2013 review, which included randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials, evaluated PRP for soft-tissue injuries.25 The primary outcomes were functional status, pain, and adverse effects. PRP was compared to placebo, autologous whole blood, and dry needling. According to the authors, “[T]here is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of [platelet-rich therapies] for treating musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries.”25

- Sports injuries: In a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, the authors concluded that PRP was no more effective in treating sports-related injuries than other treatment options.18

Because there is currently no standardization for the PRP solution and application, the clinical outcomes of PRP treatment vary widely. Results are influenced by a number of different factors:

- clinical application of PRP, ie, what it is being used to treat

- the number of injection areas treated

- the number of actual injections

- ultrasound-guidance with the injections

- the PRP and leukocyte concentration

- the frequency of application

Case History

A 72-year-old female patient presented with chronic left groin, hip and leg pain. I administered ultrasound-guided injections of PRP and ozone to the left hip (see Figure 2). It is difficult to appreciate the degree of moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis in this ultrasound image. The joint capsule is enlarged in this picture following ultrasound-guided injections of PRP and ozone.

Figure 2. Ultrasound Picture of Left Hip after Injections

Figure 3 is an X-ray of the patient’s pelvis and left hip joint that more clearly illustrates the moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis of the left hip joint; it also demonstrates the asymmetry of the pelvis. I treated the patient’s left hip with 1 ultrasound-guided prolotherapy treatment and 3 separate ultrasound-guided PRP treatments, each 1 month apart. The patient responded very well to her treatments, reporting significant pain reductions in her left hip, groin, and left leg. She was also referred to a chiropractor for treatment of the pelvic misalignment.

Figure 3. A-P X-ray of Pelvis & Lumbar Spine

PRP Combinations

Combinations of PRP with gels, scaffolds, and/or stem cells represent exciting applications worthy of exploration. Different studies, for example, have shown the benefits of combining PRP with bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC)26 or amniotic allograft.27

Dr Frank Shallenberger recommends combining PRP and ozone for all PRP applications.28 I administer ozone after all my PRP injections. Although the technique of combining PRP with regenerative solutions such as alpha-2-macroglobulin or exosomes can be found on various practitioners’ websites, evidence is lacking in the literature as to its effectiveness.

Patient Selection, Evaluation, & Safety

As with any regenerative joint procedure, PRP is not a cure for all painful musculoskeletal conditions. Practitioners must be realistic in their selection of each case. Before treatment, each patient should be evaluated on an individual basis with a through history, physical exam with relevant orthopedic tests, and diagnostic testing, which commonly includes X-rays, MRIs, ultrasound evaluation, and full laboratory work-up.

PRP & Ultrasound

Compared to other regenerative solutions, such as prolotherapy and prolozone, PRP is more expensive and the volume of solution is limited. As a result, using ultrasound to guide injections is particularly valuable for achieving precise needle placement, especially for deeper injections.

Learning PRP

The same principals practiced in prolotherapy and prolozone also apply to PRP. For example, the beginning regenerative medicine practitioner should follow the same steps to learn human anatomy as recommended for other regenerative joint injections. Some of the more commonly recognized organizations that teach injection procedures include the American Osteopathic Association of Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine, the American Association of Osteopathic Prolotherapy, and the Hackett-Hemwall-Patterson Foundation. The Neil Riordan Regenerative Medicine Center at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM) also offers prolotherapy training to doctors, which includes both lecture and “hands-on” injection experience.

Summary

PRP is an autologous, orthobiologic product that is derived from the patient’s own blood. It is a safe, natural, non-drug, non-surgical treatment that harnesses the body’s natural healing power to stimulate collagen tissue regeneration and strengthen weakened ligaments and tendons. There are inherent healing growth factors in PRP that stimulate tissue regeneration. There is a wide variety of treatment applications of PRP in orthopedics, aesthetics, and male and female sexual function. There is a definite need for standardization regarding its use, to achieve optimum therapeutic benefit. The clinical outcome of PRP is dependent upon both the PRP solution and application. Although the reported efficacy of this treatment varies in the literature, this regenerative medicine technique has repeatedly demonstrated successful outcomes for a variety of conditions. The patient should be properly selected and evaluated to ensure optimum outcome. The practitioner should have an in-depth knowledge of anatomy and have taken the time to develop palpation skills. It is this author’s opinion that PRP should be considered as a logical first step in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions before considering surgery, including joint replacement.

References:

- Gordin K. Comprehensive Scientific Overview on the Use of Platelet Rich Plasma Prolotherapy (PRPP). Journal of Prolotherapy. 2011;3(4):813-825. Available at: http://journalofprolotherapy.com/comprehensive-scientific-overview-on-the-use-of-platelet-rich-plasma-prolotherapy-prpp/. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- Dhillon MS, Behera P, Patel S, Shetty Y. Orthobiologics and platelet rich plasma. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(1):1-9.

- Shiel WC. Medical Definition of Autologous. MedicineNet. Available at: https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=13210. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- Ferrando J, Garcia-Garcia SC, Gonzalex-de-Cossio AC, et al. A Proposal of an Effective Platelet-rich Plasma Protocol for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2017;9(4):175-170.

- Modarressi A. Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) Improves Fat Grafting Outcomes. World J Plast Surg. 2013;2(1):6-13.

- Motosko CC, Khouri KS, Poudrier G, et al. Evaluating Platelet-Rich Therapy for Facial Aesthetics and Alopecia: A critical Review of the Literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(5):1115-1123.

- Scott S, Roberts M, Chung E. Platelet-Rich Plasma and treatment of Erectile Dysfunction: Critical Review of Literature and Global Trends in Platelet-Rich Plasma Clincs. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(2):306-312.

- Runels C, Melnick H, Deborbon E, et al. A Pilot Study of the Effect of Localized Injections of Autologous Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) for the Treatment of Female Sexual Dysfunction. J Women’s Health Care. 2014;3(4). Available at: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/a-pilot-study-of-the-effect-of-localized-injections-of-autologous-platelet-rich-plasma-prp-for-the-treatment-of-female-sexual-dysfunction-2167-0420.1000169.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- Reinders M, Haghighat S. Modified Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) for cruciate ligament injuries in dogs. June 20, 2019. Innovative Veterinary Care. Available at: https://ivcjournal.com/prp-cruciate-ligament-injuries/. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. Health Encyclopedia. What Are Platelets? Available at: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?ContentTypeID=160&ContentID=36. Accessed December 22, 2019.

- Baumgartner J. PRP: Evidence Based Regenerative Medicine. [Presentation]. Research Symposium: The Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Chronic Myofascial Pain with Prolotherapy. October 17-19, 2019. Madison, WI.

- Le ADK, Enweze L, DeBaun MR, Dragoo JL. Current Clinical Recommendations for Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(4):624-634.

- Arnoczky SP, Caballero O, Yeni YN. Platelet-rich Plasma to Augment Connective Tissue Healing: Making Sense of it All. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(7):445-448.

- Weibrich G, Hansen T, Kleis W, et al. Effect of platelet concentration in platelet-rich plasma on peri-implant bone regeneration. Bone. 2004;34(4):665-671.

- Clark GB. Clinical BioTensegrity in Orthopedic Medicine. [Presentation]. October 20, 2018. Hackett-Hemwall-Patterson Foundation with the University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI.

- Di Y, Han C, Zhao L, Ren Y. Is local platelet-rich plasma injection clinically superior to hyaluronic acid for treatment of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):128.

- Fitzpatrick J, Bulsara MK, McCrory PR, et al. Analysis of Platelet-Rich Plasma Extraction, variations in Platelet and Blood Components Between 4 Common Commercial Kits. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(1):2325967116675272.

- Gholami M, Ravahi H, Salehi M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the application of platelet rich plasma in sports medicine. Electron Physician. 2016;8(5):2325-2332.

- Kearney RS, Parsons N, Metcalfe D, Costa ML. Injection therapies for Achilles tendinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD010960.

- Andia l, Maffulli N. Muscle and tendon injuries: the role of biological interventions to promote and assist healing and recovery. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(5):999-1015.

- Dhillon MS, Patel S, Bansal T. Improvising PRP for use in osteoarthritis knee – upcoming trends and futuristic view. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(1):32-25.

- Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):16.

- Meheux CJ, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, et al. Efficacy of Intra-articular Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(3):495-505.

- Fitzpatrick J, Bulsara M, Zheng MH. The Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Tendinopathy: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):226-233.

- Moraes VY, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, et al. Platelet-rich therapies for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD010071.

- Kim SJ, Song DH, Park JW, et al. Effect of Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate-Platelet-Rich Plasma on Tendon-Derived Stem Cells and Rotator Cuff Tendon Tear. Cell Transplant. 2017;26(5):867-878.

- Davis A, Augenstein A. Amniotic Allograft Implantation for Midface Aging correction: A Retrospective Comparative Study with Platelet-Rich Plasma. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(5):1345-1352.

- Shallenberger F. Ozone Certification Course. 2013. Carson City, NV.

Fred G. Arnold, DC, NMD, graduated from Palmer College of Chiropractic in 1983 and from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2006. Dr Arnold has over 29 years of clinical experience. He runs a private practice in Scottsdale, AZ (Scottsdale Pain Rehabilitation and Wellness), which specializes in regenerative joint injections. Dr Arnold is certified in Prolotherapy by the American Association of Orthopedic Medicine (AAOM). He is also a Fellow in both the Anti-Aging & Regenerative Medicine and the American Academy of Ozonotherapy (FAAOM).