Marie-Sabine Thomas, ND, LMP

Marie-Sabine Thomas, ND, LMP

Ibukun (Ibby) Omole ND, LAC

Karen Hurley, ND

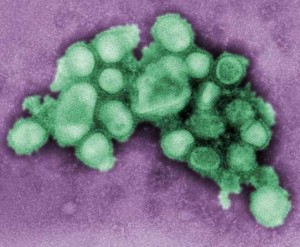

As another winter season approaches, the medical community across the world faces the multitude of concerns and questions regarding the seasonal flu shot and, most recently, the pandemic of influenza A/H1N1. Queries about vaccine safety, prevention and precaution methods are inevitably faced by the naturopathic primary care physician. Aside from the current health agency recommendation, there are inferred daily sociocultural implications for various communities, many of whom are considered to be at higher risk of exposure to H1N1.1

As a highly contagious virus, the first H1N1 viral outbreak in the United States was detected in April 2009.2 By August 2009 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that laboratory confirmed H1N1 virus infections had claimed 9,079 hospitalizations and 593 deaths. By summer 2009, its incidence-related hospitalizations and death had exceeded what had normally been expected for this time of year. This prompted a swift response from national and international health agencies that pushed the manufacture and selective availability of H1N1 vaccines.

The CDC asserts that the most efficient way to prevent the infection is through vaccination, hence the following groups have been identified as priority for vaccination against H1N1: pregnant women, individuals living with or caring for children younger than 6 months, healthcare and emergency medical services personnel, all individuals aged 6 months to 24 years, and individuals aged 25-64 years who risk medical complications from influenza.3

A Priority Group: Pregnant Women

Substantial vaccination safety data is relatively non-existent4 for pregnant women. Nevertheless, they are under the most cultural pressure and scrutiny for protecting themselves and their unborn fetus. This is primarily due to the fact pregnant women are 4 times as likely to get hospitalized once they become infected with H1N1.5 Yet there are still questions raised about the effect that the vaccine may have on the pregnancy and on the fetus. For this reason, in September 2009, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) launched an H1N1 vaccine trial (the first of its kind) with pregnant women as subjects.6 A study in the Journal of Reproductive Medicine conducted on acceptance of a pandemic avian influenza vaccine in pregnancy concluded that of the nearly 400 hundred obstetric patients surveyed, only 15.4% stated they would definitely accept a pandemic influenza vaccine in pregnancy, despite most (68%) reporting they would first consult their obstetrician for information. Of the office personnel in obstetric offices, 50% would not recommend a pandemic influenza vaccine to pregnant women, and 40% reported unwillingness to accept the same vaccine if they themselves were pregnant.7 It is also probable to foresee that communities with higher pregnancy rates will be targeted. In Canada, for example, this is reflected in efforts being pushed in Native Communities where birth rates are at their highest.8

In the United States, the 2009 National Vital Statistics Reports show that the birth rates at their highest, respectively, are amongst the Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, American Indian or Alaska Native communities.9 One aspect to consider is that lack of adequate prevention is associated with poor access to and poor quality of healthcare. Both concepts earmark existing health disparities among certain expectant women in the United States. Although pregnant mothers may receive the H1N1 flu shot, would this translate into an adequate prenatal care visit? Ultimately the quality of care may be a predictor not only for infant mortality, but also adequate follow-through in case of side effect secondary to vaccination.

Socioeconomics

An NPR interview conducted in August 2009 of Dr. Anita Barry of the Boston Public Health Commission showed that Latinos and African-Americans in certain Boston school neighborhoods were at higher risk of contracting H1N1.10 The interview further revealed that most parents of the affected children could not afford to provide childcare in order to keep the children out of school. This example shows that prevention goes beyond health agency recommendations. Prevention is therefore most importantly affected by the communities’ socioeconomic level. There is nothing about the new flu virus itself that makes minorities more likely to get sick from it; socioeconomic factors, however, are social determinants of health. One of the major prevention initiatives may not work for these affected communities as the parents cannot afford to leave their low-wage paying job to be at home with their children. The dread of having sick children at home and having to miss work days would naturally lead parents to seek the H1N1 vaccinations for their loved ones. Unfortunately, this is one population example that doesn’t weaken the impetus for compulsory vaccination pushed in certain communities.

While our goal should not be to scare patients away from what could be a significant form of protection against H1N1 in being vaccinated, we also find that there are too many unanswered questions given the relative newness of this vaccine. Our best advice is to remind our patients to maintain the basic principles of prevention and to remain educated on the matter the best they can. The H1N1 flu has prompted massive herd immunity distress and one of our roles is to sort what is relevant from what isn’t. Armed with the knowledge that because of their existing sociocultural and economic status certain communities are more affected than others, we should as holistic healthcare practitioners be especially diligent in increasing our outreach, diversifying our printing information (language and reading level) and reaching out to communities that may still not be able to take the basic precautions and prevention.

Marie-Sabine Thomas, ND, LMP is a NIH/NCCAM Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Bastyr University Research Institute. She graduated from Mount Holyoke College with a B.A. in Socio-medical Sciences and received her Naturopathic Doctorate Degree from Bastyr University. Her research interests are Complementary Alternative Integrative Medicine (CAIM) and Community Health and Health Disparities.

Ibukun (Ibby) Omole ND, L.Ac. graduated from Bastyr University with a degree in Naturopathic Medicine and a Masters in Acupuncture. Dr. Omole’s specialty is in urological conditions such as incontinence, overactive bladder, neurogenic bladder, interstitial cystitis, BPH pelvic pain and other pain conditions. Information regarding her practice can be found at www.saccomole.com.

Karen Hurley, ND is a graduate of Bastyr University. She is currently adjunct faculty at Bastyr where she teaches classes in herbal medicine, counseling psychology and naturopathic clinical science. When not teaching Dr. Hurley practices naturopathic family medicine integrating lifestyle counseling, homeopathic, herbal, nutritional and cranial sacral therapeutic approaches.

References

1. Public Health, Seattle and King County. General information community organizations and human service providers. http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/preparedness/pandemicflu/swineflu/community.aspx. Accessed October 16, 2009.

2. Bronze MS. H1N1 influenza (swine flu). E-Medicine (Medscape) Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1673658-overview Updated October 26, 2009. Accessed October 12, 2009.

3. Questions and answers: 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine. Center for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/vaccination/public/vaccination_qa_pub.htm. Updated October 16, 2009. Accessed October 16, 2009.

4. Kaposi C. The H1N1 Vaccine and pregnant women, Bioethics Forum, October 6 2009. http://www.thehastingscenter.org/Bioethicsforum/Post.aspx?id=3956&terms=The+H1N1+Vaccine+and+pregnant+women+and+%23filename+*.html. Created October 6, 2009. Accessed October 15, 2009.

5. Use of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR August 21, 2009;58(Early Release):1-8]. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr58e0821a1.htm . Accessed October 28, 2009.

6. NIAID launches 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine trial in pregnant women. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Web site. http://www.nih.gov/news/health/sep2009/niaid-09.htm. Accessed on October 19, 2009.

7. Beigi RH, et al. Acceptance of a pandemic avian influenza vaccine in pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2009;54( 6):341-346.

8. Guidance on H1N1 flu vaccine sequencing. Public Health Agency of Canada Web site. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/alert-alerte/h1n1/vacc/pdf/monovacc-guide-eng.pdf. Updated September 16, 2009. Accessed October 27, 2009.

9. Martin JA, et al. Births: final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2009;57(7):5. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_07.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2009.

10. Knox R. Officials find swine flu hits minorities harder. August 19, 2009. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=112035625. Accessed October 27, 2009.