Robin DiPasqualey, ND

In 1923, the Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded for the discovery of insulin, given to Frederick Grant Banting and John James Rickard, who shared the prize with 2 other members of their research team, James Bartram Collip and Charles Herbert Best. Collip named insulin glucokinin because of its metabolic activity rather than its place of origin. Glucokinins are substances with insulin-type action, coming from plants with guanidine derivatives, able to decrease blood glucose levels. Metformin, a biguanide, is a derivative of an active natural product, galegine, a guanidine isolated from Galega officinalis (goat’s rue).1

Just 88 years later, the incidence of diabetes mellitus has increased significantly, with 18.8 million Americans diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and 7 million more who have diabetes and are not aware of it. Although pharmaceutically prepared insulin and oral hypoglycemic substance use has increased extensively, indigenous plant medicine remains a significant part of therapeutic treatment options in many parts of the world. From an ethnobotanical perspective, T2DM is at the interface of conventional biomedical and local or traditional treatment, with plant medicine being used with and without biomedical medications.2 The literature contains articles reviewing medicinal plants from many countries and cultures throughout the world, some cited herein.

Diet and lifestyle, including regular physical exercise, are essential in the management of T2DM. With diet and lifestyle counseling as a foundation, naturopathic medicine has much to contribute to the prevention and treatment of this chronic disease. In comanagement with patients’ using insulin, oral hypoglycemic pharmaceuticals, or naturopathic medicine as stand-alone therapy, there are many resources to be considered in naturopathic therapeutics, including botanical medicine. This article will highlight a few of the botanical medicine options.

Understanding the mechanisms of action of the herbs can assist in choosing individual or formulated herbal therapies. Because T2DM is considered a disease of inflammation,3 general mechanisms to include in treatment are antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Many herbs with hypoglycemic effects will also have anti-inflammatory effects. Antioxidant support will prevent oxidative damage to body tissues, including neuropathy and retinopathy. More specific mechanisms of action, from the Western perspective and Traditional Chinese Medicine energetics, can help direct the herbal choices when crafting long-term treatment plans for individuals with T2DM, yielding a more effective outcome.

In working with a patient having T2DM, Western medicine mechanisms of action include the following:

- inhibition of intestinal carbohydrate absorption,

- improvement in insulin sensitivity,

- stimulation of insulin secretion, and

- protection of pancreatic islet of Langerhans beta cells.

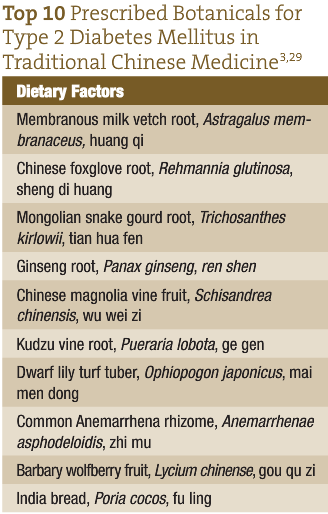

Traditional Chinese Medicine goals when working with a patient having T2DM are as follows:

- invigorate qi

- nourish yin

- clear heat

- remove stasis

Inhibiting intestinal carbohydrate absorption requires binding carbohydrates and sugars and escorting them out of the body through the colon. This can be facilitated by the use of bulking laxatives, gums, pectin, and mucilaginous substances, both in the diet and through supplementation. Plantago ovata seed (called psyllium seed on the market), Salvia hispanica (Chia seed), and Linum usitatissimum (flaxseed) all act as bulking laxatives, taken with plenty of water. Inulin is a polysaccharide that is tasteless, is not absorbed through the gut mucosa, helps satisfy hunger, and can sequester sugars and carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract and carry them out through the feces. Plants highest in inulin are Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichokes), Cichoriaum intybus (chicory), Taraxacum officinale (dandelion), and Camassia species (camas root). Be cautious and aware of the death camas, a white flowering camas that grows in patches with other camas, looks alike in the root, is categorized in the genus Zigadenus, and is extremely toxic. Inulin is also found in the root of Inula helenium (elecampane), Artium lappa (burdock root), Helianthus annuus (sunflower), and Cynara scolymus (globe artichoke).4 Guar gum, the ground endosperm of the seed of Cyanopsis tetragonoloba is a bulk laxative that delays the emptying of the stomach, protracts absorption in the gastrointestinal tract of carbohydrates and sugars, and slows the release of insulin. It too can reduce appetite.

Dietary choices will significantly influence the other 3 aforementioned mechanisms of action essential in the treatment of patients with diabetes (improving insulin sensitivity, stimulating insulin secretion, and protecting the pancreatic cells). However, specific herbal medicine choices can be applied to focus the therapeutics from a Western model and to address the energetic actions from the Traditional Chinese Medicine perspective.

Berberine

Most studies supporting the use of berberine in the management of T2DM are from Chinese researchers. Coptis chinensis (golden thread) has been used for thousands of years in the treatment of diabetes, long before the current understanding of insulin and its role in metabolism. Western herbs containing the berberine alkaloid, including Mahonia species (Oregon grape and agarita), Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal), and Berberis vulgaris (barberry), can be used in the same way for T2DM management.

In a 2008 study,5 thirty-six patients with T2DM were given berberine or metformin for 3 months. The hypoglycemic effects of berberine and metformin were similar. In another study,6 berberine (1.0 g/d) or placebo was administered to 116 patients diagnosed as having T2DM. Outcomes showed that berberine decreased glycated hemoglobin, fasting blood glucose, postprandial blood glucose, and plasma triglycerides levels, as well as reducing total cholesterol concentration. Taking berberine can increase insulin receptor expression.

Another study7 published in 2008 demonstrated that berberine inhibited intestinal carbohydrate absorption by significantly decreasing intestinal disaccharidase activity. Results showed a lowering of postprandial blood glucose and plasma triglycerides levels.

Berberine has not come into its full use in T2DM management. It has the potential to decrease the need for oral hypoglycemic agents and possibly insulin dosing, working to correct multiple mechanisms that have led to the disease. It seems to augment the effectiveness of metformin. There is a surge of interest in the effects of berberine on T2DM, which will initiate further studies.

Panax quinquefolius (American Ginseng)

In addition to the adaptogenic properties of this Araliaceae family plant, Panax quinquefolius (which is cultivated in the greatest quantity in this country in the state of Wisconsin) has significant glucose-lowering action. However, the effects could depend on whether diabetes is present or absent and whether the herb is taken with food or away from food.

In a study8 of 10 individuals without diabetes and 9 patients with diabetes, ginseng (3 g) or placebo was given either together with a 25-g oral glucose challenge or 40 minutes before the challenge. Among persons without diabetes, no difference was noted between the ginseng and placebo groups following administration of ginseng with the glucose challenge. However, when given 40 minutes before the glucose challenge, significant lowering of blood glucose level occurred in the ginseng group. Among persons with diabetes, lowering of blood glucose level occurred whether the ginseng was administered with the glucose challenge or 40 minutes before. American ginseng can be combined with Konjac-Mannan, a soluble fiber that modulates the absorption of glucose from the small intestine and increases insulin sensitivity, for prevention and treatment of T2DM.9

Momordica charantia (Bitter Melon)

Momordica charantia, known as bitter melon, has widespread use as a food and medicine in various cultures throughout the tropics, where it indigenously grows. Commonly consumed in India as a vegetable, Momordica is documented for beneficial effects of the fruit for its hypoglycemic effect.10 An ethnobotanical survey was taken of 100 traditional healers in Nigeria who treat persons with diabetes using herbal medicine. Principal antidiabetic plants included M charantia.11 In an article published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology,12 forty-five plants from the Ayurvedic materia medica were cited as showing antidiabetic activity. These plants demonstrated antiglycemic effects, enhanced beta-cell production, and increased glucose update in tissue. The following plants were evaluated in the article and showed effective outcomes in case management among persons with T2DM:

M charantia, Eugenia jambolana, Mucuna pruriens, Tinospora cordifolia, Trigonella foenum-graecum, Ocimum sanctum, Pterocarpus marsupium, Murraya koeingii, and Brassica juncea.

However, a literature search performed in 2010 showed only one randomized controlled trial looking at the effects of M charantia leaf extract compared with glibenclamide, demonstrating similar efficacy.13 The conclusion of the study was that there is insufficient evidence available to recommend Momordica.

In considering M charantia for the treatment of T2DM, its use throughout history has shown effective outcomes. Paying attention to the part of the plant eaten (the fruit), the preparation, and the application within herbal formulas are important details to understand its therapeutics.

Gymnema sylvestre (Gurmar in the Ayurvedic Tradition)

Gymnema is often referred to as the sugar destroyer. It can take away the taste of sweetness on the tongue temporarily when taken directly in the mouth. Among 800 plants that have traditionally been used for treatment of T2DM, a systematic review observed that the following 6 herbs demonstrated positive clinical effects:

- Gymnema sylvestre (gurmar)

- Coccinia indica (ivy gourd)

- M charantia (bitter melon)

- Aloe vera (aloe)

- P quinquefolius (American ginseng)

- Opuntia streptacantha (prickly pear cactus)14

Gymnema sylvestre has been shown to have the following actions:

- decreases uptake of glucose from the intestine15

- improves glycogen synthesis, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and hepatic and muscle glucose uptake16

- reverses hemoglobin and plasma protein glycosylation17

- stimulates insulin release from islet of Langerhans cells18

- has antagonistic effects on somatotropin, corticosteroids, and adrenaline-induced hyperglycemia19

- attenuates the insulinotropic action of gastrointestinal hormones and an increase in peripheral insulin sensitivity20

In a study21 published in 2001, sixty-five patients consumed the leaf extract of G sylvestre (400 mg twice a day) for 90 days. The outcomes showed decreased preprandial and postprandial blood glucose levels and glycated hemoglobin level. In another study22 comparing Gymnema with glibenclamide, 22 patients were given combined Gymnema and glibenclamide or glibenclamide alone for 18 to 20 months. The combination group demonstrated decreased blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, and glycosylated plasma protein levels and increased release of islet of Langerhans cells; the glibenclamide-only group showed no change or an increase in the first 3 markers.

Brickellia species

In a review of 306 species popularly used to treat diabetes in Mexico, 93 plant families were represented.23 Forty-seven of these plants were in the Asteraceae family and 27 in the Fabaceae family, the top 2 represented plant families. Among these, Brickellia veronicaefolia was 1 of 7 species reviewed for its medicinal activity. Hamula, as B veronicaefolia is called in Mexico, is referred to as oregano de monte because of its use to treat gallbladder problems and stomach pain. Its hypoglycemic activity was reported in a study24 performed in Mexico in which the upper part of the plant was used when in flower, 1 to 3 teaspoons per cup of hot water, steeped for 15 to 20 minutes. It has a bitter taste. There is also a study25 on the aldose reductase activity of the flavonoids found in Brickellia, which can yield protective effects against neuropathy, retinopathy, and cataract development.

Opuntia Species

Opuntia, the prickly pear cactus, was part of the food and medicine of the Aztecs and Anasazi. Studies from Mexico and the southwest United States have shown metabolic effects of Opuntia species. One study26 demonstrated that Opuntia decreases blood glucose levels 10 to 30 mg/dL (to convert glucose level to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555). Eight patients with T2DM showed a dose-dependent response with 300 g of broiled pads, yielding a mean decrease of 30 mg/dL, while 500 g yielded a mean decrease of 45 mg/dL. A decrease in glucose level was noted within the first hour after ingestion, with a more significant decrease 2 to 3 hours after consumption. In another study,27 little or no reduction of glucose or insulin levels was seen with Opuntia in normoglycemic volunteers. The traditional preparation is to cut up the pad, prepare a cold infusion, and drink the water throughout the day. Broiling the pad and juicing the pad have also shown beneficial results. A recent study28 showed effective hypoglycemic activity of polysaccharides from Opuntia dillenii, with a proposed mechanism through protection of peroxidation damage in the liver, improving the sensitivity and response of target cells to insulin.

Dr Dimiter Pamukoff,30 pioneer of scientific phytotherapy, stated in his blog that his favorite herbal tea mixture with insulinlike substances to normalize blood glucose levels is honeybush and rooibos. Members of the Fabaceae family, these 2 herbs hail from South Africa: honeybush (Cyclopia species) is called heuningbos in Afrikaans, and redbush (Aspalathus linearis) is called rooibos in Afrikaans).

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH (AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medi-cine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health sys-tems at the University of Washington in the CAM certifi-cate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH (AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medi-cine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health sys-tems at the University of Washington in the CAM certifi-cate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

References

- Witters L. The blooming of the French lilac. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1105-1107.

- Andrade-Cetto A, Heinrich M. Mexican plants with hypoglycaemic effect used in the treatment of diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:325-348.

- Xie W, Du L. Diabetes is an inflammatory disease: evidence from traditional Chinese medicine. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(4):289-301.

- Frenck A, Leenheer L. Inulin reference www.wiley-vch.de/books/biopoly/pdf…/bpol6014_439_448.pdf.

- Yin J, Xing H, Ye J. Efficacy of berberine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57(5):712-717.

- Liu L, Yu YL, Yang YS, et al. Berberine suppresses intestinal disaccharidases with beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic states: evidences from in vivo and in vitro study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381(4):371-381.

- Zhang Y, Li X, Zou D, et al. Treatment of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia with the natural plant alkaloid berberine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2559-2565.

- Vuksan V, Sievenpiper JL, Koo VY, et al. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L) reduces postprandial glycemia in nondiabetic subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(7):1009-1013.

- Vuksan V, Sievenpiper JL, Xu Z, et al. Konjac-Mannan and American ginseng: emerging alternative therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(5)(suppl):370S-383S.

- Platel K, Srinivasan K. Plant foods in the management of diabetes mellitus: vegetables as potential hypoglycaemic agents. Nahrung. 1997;41(2):68-74.

- Gbolade AA. Inventory of antidiabetic plants in selected districts of Lagos State, Nigeria. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121(1):135-139.

- Grover JK, Yadav S, Vats V. Medicinal plants of India with anti-diabetic potential. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81:81-100.

- Ooi CP, Yassin Z, Hamid TA. Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD007845.

- Leach M. Gymnema sylvestre for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(9):977-985.

- Porchezhian E, Dobriyal R. An overview on the advances of Gymnema sylvestre: chemistry, pharmacology and patents. Pharmazie. 2003;58(1):5-12.

- Shanmugasundaram KR, Panneerselvam C, Samudam P, Shanmugasundaram ER. Enzyme changes and glucose utilisation in diabetic rabbits: the effect of Gymnema sylvestre, R.Br. J Ethnopharmacol. 1983;7(2):205-234.

- Shanmugasundaram E, Venkatasubrahmanyam M, Vijendran N, Shanmugasundaram K. Effect of an isolate from Gymnema sylvestre, R.Br. in the control of diabetes mellitus and the associated pathological changes. Ancient Sci Life. 1988;7:183-194.

- Baskaran K, Kizar Ahamath B, Radha Shanmugasundaram K, Shanmugasundaram ER. Antidiabetic effect of a leaf extract from Gymnema sylvestre in non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990;30(3):295-305.

- Srivastava Y, Nigam S, Bhatt H, et al. Hypoglycemic and life-prolonging properties of Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract in diabetic rats. Isr J Med Sci. 1985;21:540-542.

- Okabayashi Y, Tani S, Fujisawa T, et al. Effect of Gymnema sylvestre, R.Br. on glucose homeostasis in rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;9:143-148.

- Joffe D. Gymnema sylvestre lowers HbA1c. Diabetes Control Newsl. 2001;76:e1. http://www.diabetesincontrol.com/studies/. Accessed June 30, 2011.

- Baskaran K, Kizar Ahamath B, Radha Shanmugasundaram K, Shanmugasundaram E. Antidiabetic effect of a leaf extract from Gymnema sylvestre in non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990;30:295-305.

- Andrade-Cetto A, Heinrich M. Mexican plants with hypoglycaemic effect used in the treatment of diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:325-348.

- Pérez-Gutiérrez RM, Pérez-González C, Zavala-Sánchez MA, Pérez-Gutiérrez S. Hypoglycemic activity of Bouvardia terniflora, Brickellia veronicaefolia, and Parmentiera edulis [in Spanish]. Salud Publica Mex. 1998;40(4):354-358.

- Rosler KH, Goodwin RS, Mabry TJ, Varma SD, Norris J. Flavonoids with anti-cataract activity from Brickellia arguta. J Nat Prod. 1984;47(2):316-319.

- Aguilar C, Ramirez C. Opuntia (prickly pear cactus) and metabolic control among patients with diabetes mellitus [abstract]. Annu Meet Int Soc Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12:14.

- Frati-Murnari AC, Yever-Garcés A, Islas-Andrade S, Ariza-Andráca CR, Chávez-Negrete A. Studies on the mechanism of “hypoglycemic” effect of nopal (Opuntia sp.) [in Spanish]. Arch Invest Med (Mex). 1987;18(1):7-12.

- Zhao LY, Lan QJ, Huang ZC, et al. Antidiabetic effect of a newly identified component of Opuntia dillenii polysaccharides. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(809):661-668.

- Bensky D, Gamble A. Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica. Seattle, WA: Eastland Press Inc; 1986.

30. Phyto Health Press. Plants and food help diabetes. http://phytohealth.wordpress.com/2011/02/01/plants-and-food-help-diabetes/. Accessed June 28, 2011.