Education

David J. Schleich, PhD

Since 2001 the Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges (AANMC) has been promoting the naturopathic profession in North America from its educational perch. One top-of-mind focus all this time has been recruitment of new cohorts of students. In the decade just winding down, the AANMC has developed and deployed abundant, persuasive information on a growing digital platform about our schools and programs. It has championed the need across our network of programs for a new era of outreach including mobile advertisements via digital billboards and retargeting, alongside advertising campaigns built on Google, You Tube, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest, and Twitter. SEO (search engine optimization) is top of mind for the AANMC strategy, paying attention to everything from email marketing funnels and email referral campaign buildouts to geo fencing and yield retargeting.

The long-term impact of that effort is essential to the professional formation of naturopathic doctors in North America. An accompanying mission is to support a robust dialogue about the content, form, and cost of the preparatory education and entry certifications into practice. Along with its member schools, the AANP, state associations, specialty certifying groups, the INM and the CNME, the AANMC is a recognized purveyor of information and ideas about naturopathic medical education, professional employment opportunities, and, lately, about the growing impact of naturopathic research on the drift toward integration with mainstream biomedicine. Its work is also about accessible and effective patient care, research, and public education. The AANMC is about a sustainable, alternative path for the wellness of Americans and Canadians.

With year number 18 well underway in the association’s history, what lies ahead for this group, given the gyrations in post-secondary enrollment in America to contend with, and acknowledging the drift to integration with biomedicine within and without? With the United States and Canada’s small and robust system of naturopathic medical education at its core, and competing above its weight class, as John Weeks has described it, the AANMC is especially key to professional formation. The association’s work is about keeping the continuum of our educational efforts viable, vibrant, relevant, innovative, diverse, and culturally competent.

A special burden of the AANMC is its tireless advocacy for patients. The promotion of natural medicine and person-centered preventative health is key to not only attracting and keeping students who become naturopathic doctors, but also to guarding against tolerating the lock-down of deep pharmaceutical dependence and chronic disease levels never before experienced with such alarm and cost. With one eye on learning and academic leadership, the association’s other eye is on policy and advocacy initiatives, both regionally and federally. In the last 2 decades, much has been accomplished by the many diligent AANMC volunteer members from our various universities, colleges, programs, and the field. As the next decade looms and beckons, there are over 2700 full-time students in our schools, served by 340 full-time- and over 500 part-time faculty. These remarkable people serve thousands of patients annually.

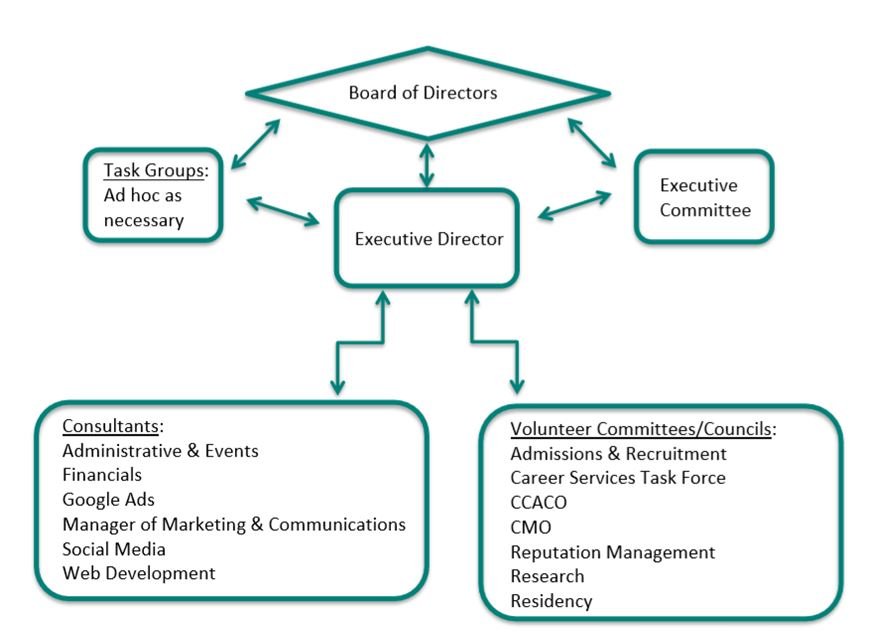

First, let’s have a quick look at how the AANMC is set up.

Figure 1. Current Organizational Structure of the AANMC

The AANMC is a Voluntary Federation

The AANMC is a voluntary, member-fee-funded federation of programs within universities and colleges. There are structural differences among those member institutions which have arisen over the years because of these variations in where the programs reside within operating budgets and governance arrangements. The complex interplay among the naturopathic, holistic, integrative, and alternative and complementary professions is another important variable affecting the AANMC’s mission, mandate, and priorities. That interplay cajoles identity issues not only for potential and matriculated students, but also for our doctors in the field and their patients. Accompanying this ferment, there is also the matter of changing employment patterns for graduates in this scenario.

Into the mix are the undulations within the naturopathic profession itself about how to hold onto its philosophical and clinical traditions at the same time as it operates successfully in a market dominated by the orthodox, allopathic paradigm and by the political forces tied to cash flow, brand, and regulation. Meanwhile, patient-up attractors propel us into primary-care status in a number of states, with more in the queue. Into this same urgent space, our research activity has accelerated this drift and supports the inclusion of treatment protocols and the pressures of primary-care standards of care.

All these often-contrary imperatives take their toll on how naturopathic physicians differ from others in the medley of types of providers flashing business cards with words such as “integrative” and “holistic” as monikers of their work. Where then, in this chaotic milieu, might the AANMC with its tight resources concentrate its efforts? Is a more secure and bigger share of the shifting biomedicine market in which our graduates operate our objective? Or does the profession really yearn, in the end, to return to a more traditional scope? The terrain has changed a lot as AANMC closes in on its 20th birthday: more promise, more danger; more opportunity, more competition.

The Déjà vu of Opportunity & Danger

These questions are not entirely rhetorical, largely because the formation of naturopathic medicine as a distinct, heterodox medical system is a fact. It is located in a landscape of health care where the cherry-picking of modalities by biomedicine is occurring with impunity and is well along the assimilation path. There are more than a few long-serving naturopathic physicians out there who worry that naturopathic medicine will suffer the same fate as the osteopathic profession in America – coopted to the point where education and licensing emanate from the same accountable bodies. The Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges can be a powerful catalyst and incubator in the hot spots and cantankerous price points in this transitional, formational period. There is nothing rhetorical about a trend which suggests that our AANMC faces a future where confident and energized proactivity will trump polite and cautious reactivity.

Let us consider the kinds of tasks and purposes for the AANMC in its second decade which lend themselves more to the former.

- Scaling awareness in the post-secondary and higher education sectors in the United States and Canada that naturopathic medical education is a higher education discipline and a professional career pathway; content generation is needed

- Raising awareness that naturopathic medical research in prevention and treatment is occurring by routinely documenting activity in a timely way in both countries

- Initiating and supporting naturopathic program governance training, mentorship, and coherence

- Ramping up broad student recruitment using well designed digital as well as on-site strategies

- Advocacy in the higher education community for enhanced articulation agreements, opportunities for trainer of choice, and recognition of credentials, credit transfer, and content ownership

- Development and sustaining of a competitive naturopathic medical academic career path within our colleges and programs, including teacher-training certification in naturopathic medicine

- Continuous, widely shared curriculum development, inclusive of current digital methodology as well as contemporary assessment systems

- Rollout of a coordinated, integrated, national residency education program

- Generation of a system-wide academic press dedicated to natural medicine teaching, research, and public education

The dialogue among AANMC members about the present and future mission of the AANMC has been chiefly about curriculum and recruitment; however, of late it has increasingly included snippets about system financing, governance, and differentiated accountability. As well, concerns have been uttered about the role of faculty, many of whom do not participate actively in their state and national associations’ efforts toward professional formation. Whatever the features of such an ongoing conversation, the AANMC needs more money, better tools, and a broader mandate if dialogue can translate into action, as it must.

The current financial model of member fees from naturopathic colleges and programs is encumbered by falling enrollments in the near future, alongside rising costs for the key operation focus of student recruitment. The inevitable impact of increasing AANMC dues concomitantly with falling tuition revenue would be to tax tuition revenues even more, at a time when the debt burden for our graduates is already severe enough. As well, it’s the member base which is the key funding gear to turn. The AANMC is now a 501(c)(3), and there is going to be fundraising.

Refinancing the AANMC

A strategy to refinance the AANMC would have to be accompanied by a close look at governance. Currently, the nature of naturopathic medical education oversight, with the CNME standards at the epicenter, varies among the 8 CNME-accredited programs, ranging from stand-alone colleges to programs within small, regional, comprehensive universities. The ND program at NUHS, for example – because of where that program is located within the governance structure of what has been a chiropractic multi-program university – will have a different fiduciary voice than it has at SCNM, BINM, or CCNM, for example. A council of trustees, directors or governors might be a way to achieve some coherence, nurtured by the AANMC in the form of annual meetings of board members or advisory committee members addressing academic concerns, finance function matters, human resources, research capacity, or plant and property matters. The AANMC could convene such gatherings and communicate outcomes.

Manifesting from governance process is structural power. The Council of Chief Academic and Clinical Officers (CCACO) has strong administrative responsibilities within individual programs and institutions, but no fiduciary or administrative authority across the system. The various manifestations within the naturopathic community of the main program officer, the chief academic or clinical officer, shake out via differing mandates. As a case in point, the dean in a small, comprehensive university, where his or her program is one among several, has a different span of control compared to, say, the president of a stand-alone, single-program naturopathic college. This translates into varying reaction time-frames for initiatives suggested centrally within the AANMC.

A likely scenario, thinking ahead, will be that universities that begin naturopathic programs (in the fashion, say, with which the University of Michigan began its Doctor of Osteopathy program back in the early 1960s, or NUHS began its program in the early 2000s) will invariably engage chairs or associate deans whose institutional mandates are defined by their programs principally. The AANMC’s role will shift as this pattern gains purchase.

When the AANMC began, its members were all presidents. Along came Bridgeport with a dean, and then Boucher, and eventually NUHS’ naturopathic associate dean. This lattice-work of decision-making authority is not an inevitable impediment to broad action in service to the profession, but it does alter process and priority for the larger association. Even so, the AANMC’s organizational structure is quite workable. Central to its success has to be system savvy and professional formation knowledge residing in its executive director.

That leader will increasingly need to guide future-scenario building around emergent issues. One issue among many is the need to define a medical academic career path for naturopathic doctors who choose teaching and academic medicine for their careers rather than private practice. Currently, there are no tenure models in the system. One single-program college, CCNM, has unionized faculty, although the collective bargaining process does not seem to have been substantially disruptive in terms of timing and prioritizing, as is often the case in public sector environments. Whatever the culture of the hosting institution, the academic medicine of the future will entail expectations and entitlements which depart from traditional arrangements wherein adjuncts or ongoing full-load professors rotate year over year on 1 or 2-year contracts. The details of career relationships within academic medicine entail important benefits beyond the security of rolling contracts. Funded sabbaticals and study leaves are difficult in our system, not only because of limited funding, but also because cumulative entitlements are unevenly documented and priorities for projects do not benefit from a system-wide taxonomy of the most urgent development work.

Attention to establishing a formal faculty career path could be studied within the AANMC by, say, a Council of Teaching Faculties, where the practical and developmental needs of classroom and clinical teachers can be heard from among our member schools. Such a council could drill down into professional development needs, including such innovations as the creation of a unique designation called “natural medicine educator” (NME). The special training (history, therapeutic order, philosophy, public policy and regulatory affairs, inter-professional liaison) could complement all the work occurring around our schools in curriculum design, measurement and evaluation, teaching skills for special-needs students, or the impact of information technology on classroom methodology.

Whatever the project – whether it be a national job fair, curriculum exchange, liaison with other healthcare educators, collaboration on residency education including a “residency lobby” for public money – the AANMC is in a position to be the key incubator and catalyst for professional formation, beginning with our most valuable resource, our teachers.

Our future as programs of higher education supportive of an heterodox profession probably entails an era of programs taking shape under the banner of “natural health sciences” or “alternative health” or even “integrative health” (although biomedicine has assimilated this clever assimilating brand despite the wide gyrations in just what that means in terms of content and clinical acumen) in multi-program institutions. The competition to deliver such programs will come from larger, university-based “integrated medicine” and CAM (complementary & alternative medicine) venues, as these groups continue their unrelenting assimilation of modalities that the naturopathic profession has defended and strengthened for generations (eg, nutrition, mind-body medicine, and other non-invasive therapies). Eventually, some say, a public-sector institution, with cash flow from government, will launch a naturopathic program, and the game changes for the AANMC and all of us.

The modern research universities are poised to assimilate, as they have done with every major profession in the last 100 years, whatever content they decide is important to their mission. The prevailing epistemology of the universities, though, most certainly precludes them being able to teach the practice competencies linked to the modalities of our naturopathic medicine programs; herein lie the greatest strength and opportunity for the AANMC as it contemplates its second decade.

Change is Constant

There can be no complacency about cash flow, maintaining enrollments with traditional offerings, and continuing to attract high-quality staff and students. The AANMC’s change-sensing radar will have to be fine-tuned through a strategic rather than a reactive lens – one which brings quickly into focus flexibility, quick response, and agility in the marketplace, all the while advocating for the principles underlying our educational values and naturopathic medicine itself. If we simply focus on patching, re-engineering, and retooling the pieces of our various processes (eg, recruitment, curriculum design and delivery, a research agenda, new program expansion), we will miss the larger opportunities which a transformative strategic approach can generate in a short order of time. The naturopathic colleges in North America historically have exhibited “diseconomies of scale” which manifest in locked-up budgets, tacit competition, constrained growth and development, and the historically disproportionate dependence on tuition revenues. In the decade ahead, it’s new territory.

What lies at the other end of the AANMC’s second decade is a brave new world where we can thrive if we cross to this next 10-year cycle with bold ideas about collaboration, intention, and execution. That world is digital, of course. Even so, it must be anchored in the very values that spawned us.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).