David Schleich, PhD

Back in mid-September, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced that $33 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) funds would be available to train “health professionals.” This was in addition to HHS Deputy Secretary Bill Corr’s announcement of $13.4 million for “loan repayments” to nurses who “agree to practice in facilities with critical shortages and for schools of nursing to provide loans to students who will become nurse faculty” (HHS news release, 2009). These two smaller parts of the overall $500 million allotted to HHS to do something about workforce shortages under the ARRA are much valued in the biomedicine community; however, not a Lincoln penny will find its way to natural medicine programs or their students anywhere in America.

Let’s have a closer look at the six qualifying Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) programs:

- Scholarships for disadvantaged students ($19.3 million)

- Centers of excellence ($4.9 million)

- Public health traineeships ($3 million)

- Nursing workforce diversity ($2.6 million)

- Health careers opportunities ($2.5 million)

- Dental public health residency training ($810,925)

So far this year, the HHS has announced the availability of almost $200 million in ARRA workforce funds, of a total $300 million, to expand HRSA’s National Health Service Corps (NHSC). This money is aimed at student loan repayments for primary care medical, dental, and mental health clinicians who will commit to NHSC sites that accommodate underserved and uninsured people. In addition, the HRSA received $2 billion through ARRA to expand healthcare services to low-income and uninsured individuals through its health center program. To date, more than $1.3 billion of these funds have been awarded to community-based organizations across the country. In 2008, HRSA-supported health centers treated 17 million patients, 40% of whom have no health insurance. But that’s not all. The HRSA also can spend $2 billion through ARRA to “expand health care services to low-income and uninsured individuals through its health center program” (HHS news release, 2010).

Beaucoup bucks, as they say, are being diverted to this massively complex healthcare challenge in America. Everywhere, dollars are flowing, but none in our direction. As a backdrop, with a not-so-long fuse already lit, is the equally complex issue of how to pay not only for primary care itself but also for the education and training of those who would deliver it.

In some ways, these cryptically dangerous predictions presage some intriguing opportunities. There are data suggesting that the number of U.S. medical school graduates choosing primary care is declining because of personal indebtedness fears and decreasing physician incomes. In this regard, there are two other factors to contend with: a simultaneously growing and aging U.S. population and the expansion of government-financed healthcare access mandated under “Obamacare.” In fact, the biomedicine group known as the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) predicts that the United States will be short 40,000 primary care providers in the next 8 years:

The results of the 2006 AAFP Workforce Study reported that the nation will need approximately 39,000 more family physicians by 2020 in order for all Americans to achieve access to a primary care physician. In 2008, Colwill [Jack M. Colwill, professor emeritus of family and community medicine at the University of Missouri–Columbia] and others have predicted that population growth and aging will result in a deficit of up to 44,000 adult care generalist physicians by 2025. . . . Subsequent analysis and the more-rapid-than-expected decline in the production of general internists suggest that shortages of adult care generalists will be even worse than predicted, and that family physicians will be relied upon to close the bulk of that gap. (AAFP, Reprint No. 305b; see also Colwill, Cultice, & Kruse, 2008)

Nowhere in national healthcare workforce planning is there mention of natural medicine professionals. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants show up in the conversation, though, albeit not in a positive light:

The annual number of Nurse Practitioners (NP) graduating is declining by 4.5 percent every year. The number of Physician Assistant (PA) graduates, on the other hand, continues to rise (http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/21/5/174.pdf); however only a third are now entering primary care practice (www.aapa.org). While PAs and NPs remain important contributors to the primary care workforce and are an important part of the team-based approach within the Patient-Centered Medical Home model of care, their contribution will be affected by the decline in the number of graduates from NP programs as well as an increase in the percentage of PAs and NPs who practice in subspecialty disciplines rather than primary care will. (AAFP, Reprint No. 305b; see also Physician assistant and nurse practitioner workforce trends, 2005)

In this kind of landscape, naturopathic medical students are not factored into the projections. At this stage, we are figuring out how to lobby to be considered in the primary care cohort. Even if we are, however, there is the matter of financing the education to get there. Let’s do the math.

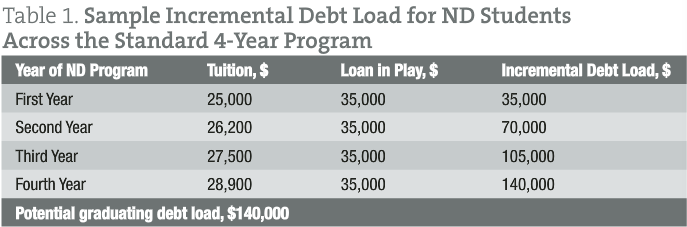

Let’s say an ND student takes out a Stafford, PLUS, or Title IV loan of $35,000 per year. Let’s further assume that the cost of tuition rises 5% in each of 4 years of a regular program, as summarized in the Table.

Many of our students obtain a residency that pays less than $40,000 per year on average. If our graduate was on a 10-year repayment plan at 6.8% and paying $1,459 per month, or $17,508 per year, that would leave less than $1000 per month in take-home income during that residency year (that’s about 1.5 the poverty level in America). These are not good numbers. We haven’t even considered the cost of practice start-up and children, who frequently happen along about the same time and eat regularly.

There are many tactics we can advise our graduates to use to get through this tough period in the life of a beginning ND. For example:

- We can tell them to be savvy about the numbers they report when their student loans come due. Often our graduates choose right off the bat to simply photocopy a couple of current pay stubs from any new job. Another approach, legal and ethical, though, is for them to use their prior year’s tax return to calculate income. Thus, a graduate who started work just after the Naturopathic Physicians Licensing Examinations (late August or early September) would be showing a lower adjusted gross income for the year, rather than an extrapolated 12-month snapshot of income.

- We can advise our graduates to lock in as soon as possible to current rates, recommending that they keep a close eye on the danger of consolidating variable-rate loans and watch for the lowest fixed-rate loans getting wrapped into higher rates.

- Our graduates should always keep a close lookout for new repayment programs. Oregon, for example, has an unfunded loan forgiveness program that NDs can access (once the faucet gets turned on).

- Our graduates need to get smart not only about not being shy regarding professional medical fees for service but also about how to lower taxable income into the bargain. Recent graduates who can afford the income-based repayment plans and have extra income to spare might make contributions to tax-advantaged retirement accounts like individual retirement accounts (presto, long-term savings with immediate lower adjusted gross income and thus lower income-based debt payments.

Despite all the odds, our graduates have had an exceptional track record managing their debt. National College of Natural Medicine’s default rate, for example, has been zero for many years. But the pressure mounts. Even all these optimistic “survive and thrive” ideas miss the point. For most of this generation, debt has been inescapable for NDs. That was not always the case. Although some of our students have personal and family resources that prevent long-term debt, over 80% of each naturopathic medical student class will graduate in debt. The image: this too shall pass. The reality: debt load is a huge boulder in the backpacks of our graduates, who to begin to earn a living have a nasty healthcare terrain to deal with in many corners of this country. Debt loads for our graduates have leapfrogged over all other economic reality checks, such as inflation and the consumer price index.

In fact, this frog in the frying pan situation has another pernicious edge to it. Even though we worry more about it than ever, we seem to consider student indebtedness as a kind of “norm” where naturopathic medical schools have generated robust tuition increases for many years. The median yearly tuition at our naturopathic college programs is approximately $24,000. The median in public medical schools is $29,000, and at private medical education institutions it is $47,000—increases from 2 decades earlier of over 312% percent and 165%, respectively. While some may insist that future NDs, MDs, and DOs can absorb over time such increases and loans, the rising debt load has had and will have repercussions on patients, particularly those in greatest need.

What is going on here? Where are all these tuition increases and skyrocketing costs coming from that are burdening our students with this kind of debt? Some of it comes from our habit of using tuition, even short term, to support long-needed institutional capital projects that the mainstream biomedicine institutions have other sources for. Steadily improving classroom and clinical facilities and long-needed research programs are good reasons. But this approach to growth is not sustainable with primarily tuition-based revenue streams. Advancement programs will definitely help. However, differentiated income streams to soften the pressure on naturopathic medical tuition sources are very important too.

Indeed, as we grow the profession, it becomes clear that standalone naturopathic medical campuses are going to be very tough to initiate and to sustain. We stand a better chance of expanding our applicant pool and serving them at lower cost if we initiate programs within existing institutions with infrastructure already in place. We don’t want our frail applicant pool to eschew a calling to serve what is a highly competitive, less lucrative patient population or practice in favor of pursuing some kind of well-compensated subspecialty catering to the comfortably insured.

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Workforce reform: Family physician workforce reform: Recommendations of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP Reprint No. 305b). Retrieved December 15, 2011, from http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/policy/policies/w/workforce.html

- Colwill, J. M., Cultice, J. M., & Kruse, R. L. (2008). Will generalist physician supply meet demands of an increasing and aging population? Health Affairs (Millwood), 27(3), w232-w241.

- Physician assistant and nurse practitioner workforce trends. (2005). American Family Physician, 72(7), 1176.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2009, August 12). News release: HHS announces $13.4 million in financial assistance to support nurses. Retrieved December 15, 2011, from http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2009pres/08/20090812a.html

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2010, June 3). News release: HHS awards $83.9 million in Recovery Act funds to expand use of health information technology. Retrieved December 15, 2011, from http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/06/20100603a.html