The Microbial Endocrine System

GUY CITRIN, ND

I assume many of my colleagues have patients who present similarly. I myself have found that my non-serious chronically ill patients often present with similar symptoms. Clinical responses to treatments, on the other hand, vary between patients. However, the further I delve into correlations between the gut microbiome and the endocrine system, the better the clinical results I seem to get.

I would say the top 10 most common symptoms I see in patients are: heartburn, bloating, indigestion, constipation/diarrhea, period irregularities and pain, low libido, anxiety, stress, fatigue, and joint pain.

As I started my career in naturopathic medicine and then learned more about how to address hormones and gut dysfunction, I noticed a significant clinical correlation between the 2. I then had the privilege of starting to lecture for Microbiome Labs, and also spent time learning from Kiran Krishnan (company founder and microbiologist), including having discussions about how the endocrine system interacts with the intestinal microbiome. Since I’ve been treating the endocrine and microbial systems as intimately connected, I have had more significant clinical success (typically 80-90% complete resolution of symptoms) and usually within 3-4 patient visits.

This shift in approach fundamentally changed my practice, so much so that I now consider the endocrine system and the microbiome as 1 unit, otherwise known as the Microbial Endocrine System. I often find that practitioners regard these systems as distinct, especially in the allopathic world. However, they are intricately tied to one another. Which leads to the question of how exactly the gut microbiome interacts with the endocrine system.

My general approach with patients is to work from top to bottom, anatomically, to find the area that seems most dysfunctional. I will leave out the mouth, although it can also have a significant effect on symptoms.

The Proximal Gut

I’ll address my clinical findings by anatomical regions and the symptoms that often correlate with them, and I hope the practitioner reading this will find it useful. Bloating is the complaint I hear about most often, and is also the one I find requires the largest amount of investigation to determine the root cause. The first question I ask the patient is whether the bloating appears immediately upon consumption of food or whether it presents 1-2 hours after eating. If the bloating occurs directly after eating or drinking water, I dig in heavily to evaluate the proximal gut.

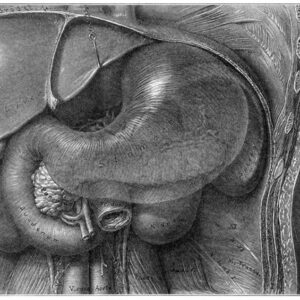

I have treated many patients effectively, even those who have tested positive for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), by addressing the proximal gut first. This reason for this, I believe, is that this system is often affected first in overall gut issues, including SIBO. The proximal gut can be the perfect storm: There are 3 main systems that come together in a very small anatomical region, and dysfunction in any of them can have significant consequences. There is stomach, gallbladder/liver, and pancreas. There is also the beginning of the small intestine and the beneficial flora that is regulated by these systems (Figure 1).

I first evaluate stomach acid, which I generally find is deficient. If there is a true lack, testing for Helicobacter pylori is useful. Ulcers can arise, as well as undigested foods and vitamin deficiencies. On the endocrine front, dopamine – the “pleasure hormone” – comes into play here. Animal studies have shown that dopamine can be produced by Bacillus spp.1,2 Additionally, various strains of H pylori appear able to alter the secretion of dopamine and serotonin, potentially contributing to mood disorders.3

I have seen much clinical benefit from restoring proper functioning in this system; I have also seen a reduction of symptoms in SIBO patients when this system is corrected. Proper amounts of pancreatic enzymes, bile, and hydrochloric acid are required for creating an environment that maintains the proper balance of bacteria in the intestine as well as in the stomach. Because bile is antimicrobial, when the biliary system malfunctions and the production or flow of bile decreases, bacteria can grow in this region, creating problems.

For all of these reasons, I tend to start out making sure my patient’s proximal gut is functioning properly.

Small & Large Bowel

If bloating occurs after 1-2 hours, it is likely microbiome related. As it is necessary to have regular bowel movements, my patients with constipation, who overuse antibiotics, and/or who have poor dietary habits are most affected in this region. The major bacterial producers of methane, hydrogen, and hydrogen sulfide are typically also the main causative agents for dysfunction. Of course, these gases can be measured in a SIBO breath test in most cases.

Along with the bloating or constipation, other microbiome-related symptoms can arise that are not as commonly thought about, such as anxiety or weight gain. Greater than 90% of serotonin in the body is produced in the gut.4 Serotonin is known to be synthesized in the bowel, but the specific mechanisms were not always fully understood. Animal studies have since revealed that mostly spore-forming bacteria in the intestine are responsible for directly signaling gut enterochromaffin cells to produce serotonin, increasing both blood and intestinal concentrations of the neurotransmitter.4 Microbial imbalances may thus promote higher amounts of luminal serotonin, which in turn can stimulate intestinal peristalsis, such as seen in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).5 Conversely, constipation-predominant IBS has been linked to excess methane, a result of methanogenic bacterial conversion of hydrogen to methane.6

Meanwhile, higher concentrations of methanogens have been shown to cause weight gain in mice, and a human study demonstrated higher body mass in index in individuals with elevated breath methane as compared to methane-negative individuals.7

On the endocrine front, stress hormones can also be affected by imbalances in the microbiome. Epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol are produced by several microbial species.2 However, beneficial bacteria can help control this stress response, specifically Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum.8 In an animal study, for instance, germ-free rats show increased HPA responsiveness compared to specific pathogen-free mice,8 and probiotic administration to mice has been shown to reduce corticosterone levels.8 Note that this HPA responsiveness is not due to adrenal dysfunction, but rather the microbiome and its impact on the endocrine system. If this research translates to humans, these effects could potentially lead to fatigue and poor immune regulation over time.

I have found that the key to treating this problem is to first address the health of the proximal gut, then to reduce pathogenic species and make sure that key strains of bacteria are present in healthy amounts, particularly Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Bifidobacterium spp.9 Increasing short-chain fatty acids (via probiotics, prebiotics, and resistant starch powder), decreasing overall immune burden by reducing inflammation in the colon, and building a healthy mucosal barrier are all ways to restore proper regulation.

Anxiety & Metabolic Endotoxemia

I have found that many of my patients with significant anxiety have intestinal dysbiosis. As discussed, dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol can all be adversely affected by the gut microbiome. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) can also be affected. For example, various strains of Lactobacillus brevis are able to produce GABA. L brevis administration to diet-induced obese mice for 12 weeks was shown to reverse several aspects of metabolic dysfunction as well as “despair-like behavior.”10

I always ask myself: Did my patient’s anxiety cause the gut issue, or vice-versa? How does the gut microbiome interplay with anxiety on a deeper level?

To understand this, let’s talk about lipopolysaccharide (LPS) toxicity and metabolic endotoxemia. LPS is a gram-negative bacterial endotoxin that is released into the lumen of the intestine upon cell lysis. This phenomenon occurs frequently, as a bacterium’s life cycle is relatively short. Circulating endotoxins such as LPS can trigger an innate immune response that results in subclinical, low-grade inflammation.11 Part of this process is the activation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-ĸB), which is known to be a major factor in many chronic diseases and overall inflammation.12 Considering the amount of LPS released into the intestine on a daily basis, failing to effectively counteract this process can have pathological significance. Ensuring mucosal health and controlling intestinal hyperpermeability (aka leaky gut) is critical in minimizing this risk.

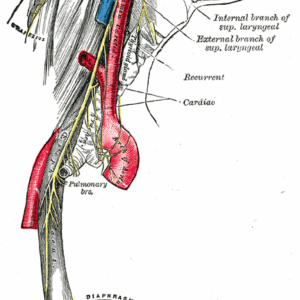

LPS can also impact the vagus nerve (Figure 2). As Pavlov and Tracey explain, “The vagus nerve regulates metabolic homeostasis by controlling heart rate, gastrointestinal motility and secretion, pancreatic endocrine and exocrine secretion, hepatic glucose production, and other visceral functions.”13 However, animal models of septic shock have shown that LPS administration induces the release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1ß and activates vagal afferent signals via IL-1ß receptors. This has the effect of activating the HPA axis in order to curb the inflammation.14 In a mouse study, LPS-induced afferent vagal nerve activation was shown to occur through toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) in the nodose ganglion.15 The sympathetic response induced by LPS may effective shut down the regulatory functions with the gut, central nervous system, and mesenteric nervous system.

So, in my patients with the major complaints of anxiety and/or weight gain, I will consider the possibility of metabolic endotoxemia, deficient GABA, LPS-induced afferent vagal nerve activation, leaky gut, and an overall over-activated innate immune response.

My treatments focus on rebuilding the mucosal barrier, decreasing systemic inflammation through identification and management of patients’ food intolerances, and increasing the keystone strains of bacteria.

Estrogen & the Microbiome

Lastly, although not 100% correlated to the above discussion, is the significant correlation between the intestinal microbiome and estrogen. Both low and elevated estrogen can be related to gut health. Intestinal microbes produce and regulate all 3 forms of estrogen: estrone, estradiol, and estriol.

The estrobolome comprises intestinal bacterial genes whose products metabolize estrogen. A notable example is the microbial enzyme, beta-glucuronidase, which deconjugates estrogen in the colon, allowing it to reabsorb into the system.16 Intestinal dysbiosis can therefore impact the level of circulating estrogens, either on the low side or high side.17 Resulting alterations in circulating estrogen, particularly estrogen dominance, may contribute to the development of conditions such as cancer, obesity, metabolic syndrome, endometrial hyperplasia, endometriosis, PCOS, infertility, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment.17

Many practitioners assume that the symptoms of estrogen dominance are purely gonadal/endocrine related. However, given the gut microbiome’s significant effects on the metabolism, regulation, and excretion of estrogen, intestinal microbial imbalances should always be considered.

When patients come into my office with symptoms of estrogen dominance and menstrual issues, I therefore often work with both the endocrine system and the gut microbial system, particularly their interrelationship, to achieve the best results.

References:

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701-712.

- Galland L. The gut microbiome and the brain. J Med Food. 2014;17(12):1261-1272.

- Meng WP, Wang ZQ, Deng JQ, et al. The Role of H. pylori CagA in Regulating Hormones of Functional Dyspepsia Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7150959.

- Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161(2):264-276.

- Sikander A, Rana SV, Prasad KK. Role of serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;403(1-2):47-55.

- Triantafyllou K, Chang C, Pimentel M. Methanogens, methane and gastrointestinal motility. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20(1):31-40.

- Basseri RJ, Basseri B, Pimentel M, et al. Intestinal methane production in obese individuals is associated with a higher body mass index. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8(1):22-28.

- Messaoudi M, Lalonde R, Violle N, et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(5):755-764.

- Verhoog S, Taneri PE, Roa Díaz ZM, et al. Dietary Factors and Modulation of Bacteria Strains of Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1565.

- Patterson E, Ryan PM, Wiley N, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid-producing lactobacilli positively affect metabolism and depressive-like behaviour in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16323.

- Fuke N, Nagata N, Suganuma H, Ota T. Regulation of Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Endotoxemia with Dietary Factors. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2277.

- Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023.

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex–linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):743-754.

- Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S. The Vagus Nerve in the Neuro-Immune Axis: Implications in the Pathology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1452.

- Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Matsuda T, Nomura Y. Novel pathway for LPS-induced afferent vagus nerve activation: possible role of nodose ganglion. Auton Neurosci. 2005;120(1-2):104-107.

- Plottel CS, Blaser MJ. Microbiome and malignancy. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(4):324-335.

- Baker JM, Al-Nakkash L, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas. 2017;103:45-53.

Guy Citrin, ND is a licensed naturopathic doctor and a member of both the California Naturopathic Doctors Association and the Endocrinology Association of Naturopathic Physicians. He is a nationally recognized speaker on gut health and restoration for Microbiome Labs. Dr Citrin received his doctorate at NUHS and was a resident at a renowned affiliate site through the University of Bastyr before relocating to Beverly Hills, CA, where he currently practices. His focus is on identifying the root cause of dysfunction, only prescribing pharmaceuticals when appropriate, and correcting dysfunction using natural means as much as possible. Dr Citrin’s specialties are gut health, hormones, and regenerative medicine. Website: https://www.doctorguy.com/.