Benedict in Europe, 1907

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

The Oberwaid is simply magnificent embracing on one side a sweep of the crystal lake and on the other a panorama of the lofty snow-clad Alps … The Alps are an uninterrupted sermon on peace and exegesis of eternity. It is no wonder that the patients who linger here return to their homes in a state of mental as well as physical regeneration. (Lust, 1908, p.54)

As I had been in Wörishofen in 1896, I went to the same place, to the institution of the Brothers of Mercy. In this establishment is located the headquarters of the Kneipp office. Here, Father Kneipp used to give his good counsel and advice and in this institution thousands and thousands of suffering human beings found health and strength.

(Lust, 1908, p.119)

The people of Adolf Just’s place come from every part of the globe. The attendance last season was about 3,000. People come and go; some stay the whole season and a good many come back every year.

(Lust, 1908, p.123)

In 1907, Benedict Lust returned to Germany after a 12-year absence from his homeland. At that point Benedict was 35 years old and he had not had the luxury of time to make the transatlantic journey often. This trip was his first since arriving in America in 1896. He would brave the crossing a second time the following year after the death of his wife, Louisa, in 1925. Certainly, he went back to visit family and friends, but he also wanted to explore diligently the sanitariums offering natural methods of healing. After over 10 years of actively promoting the Kneipp water cure and Naturopathy, he determined that it was time for him to practice what he preached. Lust published an account of his pilgrimage to these health centers in the following year, covering his travels to Germany, Switzerland, France, and England.

He visited all of the major natural health sanitariums of his day and was, in most instances, given the red carpet treatment wherever he went. His travelogue provides insights into this young man’s reach and influence globally. While building his naturopathic interests in America, he met many compelling, influential people who in their own ways were strengthening natural medicine in their corners of the world. During his travels, he crossed paths with others who shared his vision of natural medicine. Even though he was relatively young, this ambitious pioneer of our medicine had already made relationships with the Who’s Who of Naturopathy. In many ways, then, his trip to Europe was a reconnecting and a sharing with the leaders of Naturopathy. He also found time to be a tourist along the way.

A Trip to Paris and on to Germany

The record shows that his 4 days in Paris, for example, included visits to “art galleries, Eiffel Tower, Napoleon’s tomb, and other great objects of interest.” (Lust, 1908, p.52) Not surprisingly, given what we know of his tireless enterprise in America, he studied the conditions of health, health promotion, and professional formation all along the way. He was disappointed, as a case in point, that “the French people are far behind the English and out of sight of the German when it comes to a question of hygienic progress,” (Lust, 1908, p.52) It is difficult to establish, in any case, a precise chronology of Lust’s trip because he begins his travelogue with his last stop in England where he was received with great warmth and respect, meeting up with many prominent Naturists.

After Paris, Lust recounts his many adventures in Germany. He begins by describing his forays into Hamburg using “taxameter automobiles” (Lust, 1908, p.53), better known to us as taxis. In Hamburg, Lust visited a company called Mahr and Haake. This corporation would go on to become a featured supplier in his store and journals. Lust notes, “After studying and experimenting and observing for 12 years now, we unhesitatingly pronounce Mahr and Haake’s ‘Yungborn’ underwear the very best for all-round purposes.” (Lust, 1908, p.53) Clothing that breathed was the clothing that fell in line with the naturopaths’ use of the air baths. Lust encourages his readers, “I earnestly advise every reader of this magazine to secure at least one air robe; … a general toning up of the entire system is sure to result from this regular enhancing of the functions of the skin with oxygen of the air and the magnetism and elasticity of the earth having constant access to the surface of the body.” (Lust, 1908, p.53)

After visiting Frankfurt, Lust made his way to his family home in Michelbach. There, a reunion occurred with brothers, friends and other family members. His account of this family visit is enthusiastic, and included his elation about time spent with his brother, Louis Lust, who had also made the journey to Europe at the time. Louis was a baker who lived in New York City, where he operated a bakery near Benedict Lust’s health center.

Making the Rounds of German Sanitariums

Lichtenthal

In Lust’s second installment recounting his European trip, he ranks Dr Bernhard Binswanger’s “Naturist” establishment, Lichtenthal, located a few minutes from Baden Baden, as one of the best equipped sanitariums in Germany. (Lust, 1908, p.54) Lichtenthal had “an air of quiet aristocracy that makes the patients think the sanatorium does them an incalculable favor to accept their money,” an observation which Lust later shared with his colleagues in America. He proposed, “We Naturopaths in America are tempted to value ourselves too cheaply; we must affect more of reserve if our ministrations are to be estimated properly.” (Lust, 1908, p.54) Among the many exceptional features of Lichtenthal sanitarium, Lust commented on important elements such as the music he found there: “adapted, arranged and rendered as to exert specific psychological influence on various kinds of diseased states”. (Lust, 1908, p.54)

Oberwaid

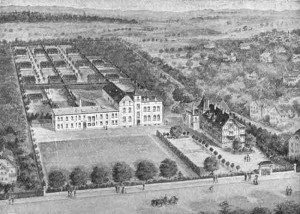

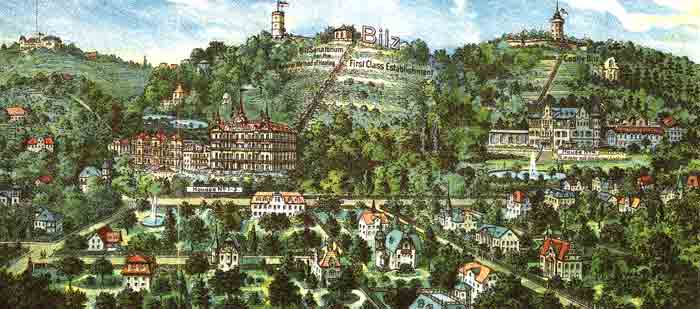

The next site that Lust references is the Sanatorium Oberwaid. Lust indicates that it was “one of the oldest Nature Cure institutions in the German-speaking world.” (Lust, 1908, p.54) He describes these 2000 acres of woodland as a “paradise of natural grandeur and repose … Oberwaid embrac[es] on one side a sweep of the crystal lake and on the other a panorama of the lofty snow-clad Alps.” (Lust, 1908, p.54) Lust contended that Otto Wagner – the owner of this sanatorium – was in the same league as Priessnitz, Rikli, and Kneipp, as a health pioneer. He points out Wagner’s feats: “He has personally founded over 1,000 Nature Cure Societies in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Russia. There is no city of inhabitants to exceed 3,000 in the whole empire where Mr. Wagner has not lectured.” (Lust, 1908, p.54) Indeed, the literature of this period shows that Wagner contributed some of the finest articles for Lust’s publications. His history in the German health field is impressive – astonishing, in fact, in range, scope and effort. Wagner had served as the clinical director at Friedrich Bilz’ palatial and enormous sanatorium (Figure 1) and then went on to lease the Bilz property, where because of his efforts and vision, the facility’s capacity was soon outgrown. Wagner then purchased the Oberwaid estate for a million francs, which had been established in 1822 by Theodore Hahn, a contemporary of Priessnitz and the pioneer of the vegetarian movement. (Lust, 1908, p.55) The Oberwaid Sanatorium was “superbly equipped with machinery and apparatus of the latest kind, and all facilities are provided for giving every treatment known to Naturopathy.” (Lust, 1908, p.55)

Figure 1. Bilz Sanitarium; 1908 The palatial Bilz Sanitarium was located among orchards and villas in Dresden – Radebeul, Germany

Oberhäuser and Landauer

Following his relaxing visit to Oberwaid, where every Nature lover could find renewal, Lust was the guest of a company called Oberhäuser and Landauer. This remarkable enterprise was the “sole authorized manufacturers of the famous Kneipp articles, such as powders, teas, oils, tinctures, soaps and herbal remedies.” (Lust, 1908, p.55) Lust studied the manufacturing practices conducted at Oberhäuser and Landauer’s facilities and was deeply impressed by their scientific rigor, efficiency, and quality controls. Lust states, “Oberhäuser and Landauer employ a small army of country folk to gather herbs where and when and how Nature made them grow.” (Lust, 1908, p.55) Kneipp gave strict instruction that no herbs were to be used that had been grown with fertilizer that rendered them inferior. Lust, in fact, was the official US importer of Kneipp products that he sold in his health food store. He was faithful to Kneipp’s standards by only using authorized products.

Third Installment of Trip

Drs Katz, Zeiher, and Baumgarten

Lust begins the third part of his Europe trip by recounting his visit to Dr Katz’s famous institution, established in 1888 at Hoehenwaldau-Degerloch, near Stuttgart (Figure 2). Lust provides a brief summary of Dr Katz’s work in medicine. Lust starts,

[Dr Katz] served in the war of 1871 as military physician. While working in this capacity, he made some observations at the hospital barracks near Strasburg. He treated 20 soldiers according to the old school methods and 20 according to the hydropathic method. Results were astonishing.

(Lust, 1908, p.116)

Dr Katz had witnessed the deleterious effects of antiseptics for the treatment of wounds, often more damaging than a benefit. (Lust, 1918, p.446) He had a prosperous and large practice, seeing over 500 patients in a season. He was a strict vegetarian; his wife, who assisted him, wrote a cookbook with Dr Katz’s dietary recommendations. Lust was also very impressed with Katz’s art gallery. Katz had on display over a hundred “oil paintings and steel engravings of every pioneer in the hydropathic, vegetarian, naturopathic field … You will find pictures there of Priessnitz, Schroth, Rausse, Strube, Balzer, Peter, Just, Lahmann, Kuhne, Rikli, Kneipp and more than 100 men.” (Lust, 1908, p.117)

The next stop was Ulm, the home of “Hermann Zeiher, [another] famous manufacturer of Kneipp’s health foods.” (Lust, 1908, p.117) A list of some of the products that Zeiher exported around the world, including Lust’s NYC store, itemized such items as “strength giving soup, kern soup, roasted flour soup, lentils, peas, beans, oats, barley, green kern, maize and mutchel flour.” (Lust, 1908, p.118) After visiting Mr Zeiher’s facility, Lust headed for Wörishofen, the very epicenter of Kneipp’s work.

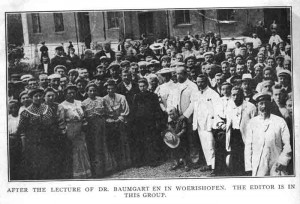

Lust had last been in Wörishofen in 1896 to recover from a near complete collapse resulting from poor living conditions, and from injuries sustained from a streetcar accident in New York City. Wörishofen was the home of Kneipp. It had grown from a “humble village to one of the foremost water cure places in Germany, visited by about 15,000 to 20,000 patients annually from every part of the world.” (Lust, 1908, p.120) Here, Lust met Dr Baumgarten, “who is one of the successors of Father Kneipp … [and who] represents the Kneipp method to the scientific world. He lecture[d] in German and French and English, and his waiting rooms are visited by people from all over the world; however, it seems only the rich, the nobility go to Baumgarten.” (Lust, 1908, p.119-120) (Figure 3) Baumgarten contributed several articles on Kneipp’s water therapies through a scientific lens, which Lust published in order to further the work of Kneipp. Lust was moved by his visit to Kneipp’s sanatorium, remembering his previous visit. He recounts his parting meeting with Kneipp many years earlier. He recalls, “Kneipp clapped me on my shoulders and said, when I left in 1896, ‘Now, my boy, do honor to the Kneipp movement in America,’ and I said I would certainly do it. I have kept my promise to this very day.” (Lust, 1908, p.120) This return to the site of his first initiation into naturopathic healing was one of great emotion for Lust. When writing about his visit to Kneipp’s tomb (Figure 4) on this trip [Kneipp had passed in 1897, very shortly after Lust’s first visit to Bad Wörishofen], Lust says, “I could not help shedding tears when standing at his tomb. I could feel his very spirit.” (Lust, 1908, p.120)

Lust then made his way to Karlsbad. Notably, his opinions of these hot thermal mineral waters were not entirely positive. His theory was that Karlsbad [Karlovy Vary] was over-stimulating, causing too much elimination. (Lust, 1908, p.121) He found the atmosphere at Karlsbad excessive, and preferred the simplicity that his own Yungborn offered.

Weiser Hirsch, Dresden

After leaving Karlsbad, Lust travelled to Dr Henry Lahmann’s famous sanitarium, Weiser Hirsch, in Dresden, known at the time as the center of the nature-cure movement (Figure 5). “[Lahmann] was a strong believer in the ‘Light and Air’ cure,” Lust writes, adding, “and [he] constructed the first appliances for the administration of electric light treatment and baths.” (Lust, 1918, p.447) Unfortunately, Lahmann had passed away 2 years prior to Lust’s visit. Even so, his sanitarium was still thriving, with much clinical activity.

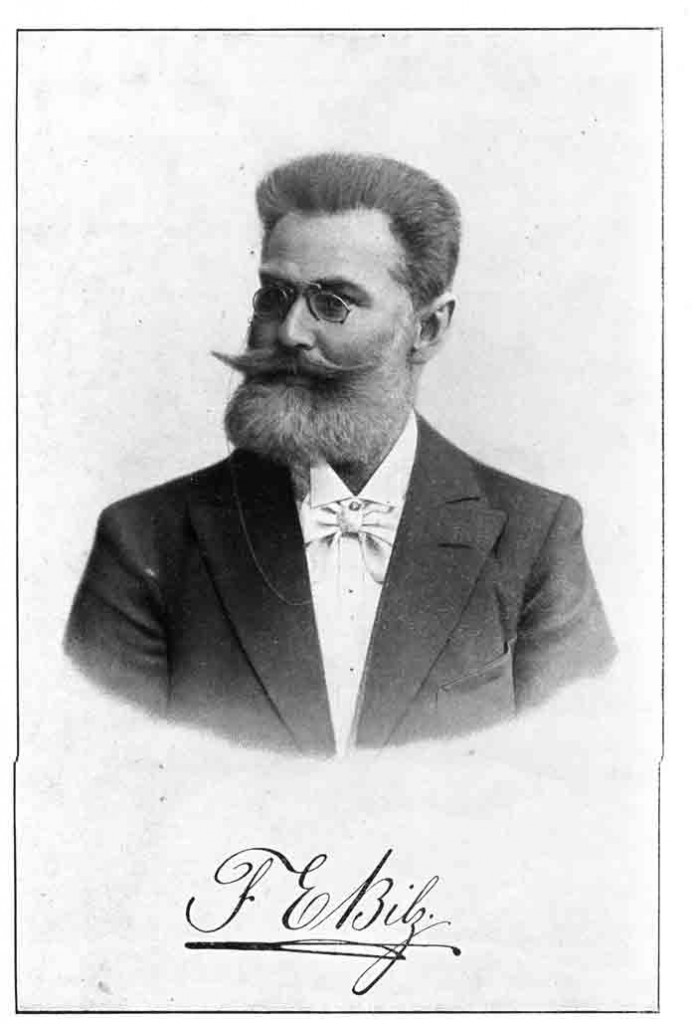

Friedrich Bilz

Following Dresden, Lust visited Friedrich Bilz in Dresden-Radebeul, “the best known of the naturopathic practitioners of the world.” (Lust, 1908, p.121) (Figure 6) Lust recounts the history of Bilz’s rise to fame. He begins, “Bilz started in 1870 with a little book and effected wonderful cures, especially with one nobleman who presented him for gratitude the present castle which Bilz occupies as a sanitarium.” (Lust, 1908, p.122) Bilz had written his colossal 2-volume set – an impressive encyclopedic work, “Natural Methods of Healing, which has been translated into a dozen languages.” (Lust, 1918, p.446) Lust stayed several days with Bilz and was treated like royalty. He “left Bilz with an impression that he is a grand old man and deserves the gratitude of every Naturopath.” (Lust, 1908, p.122)

Adolf Just’s Jungborn

After being so dazzled by the work of Bilz, Lust then went to the mecca of the Jungborn, in the Hartz Mountains, created by Adolf Just. As his account of the European journey attests, Lust’s visit with Just was the cherry and icing on the cake. This segment of his trip took first place in his Europe tour of nature-cure sanitariums. Here at “Adolf Just’s place is an institution where men, women and children learn how to stand on their own feet, how to be their own doctor.” (Lust, 1908, p.122) Lust experienced the real Jungborn and left with many ideas of improvements for his own in Butler, New Jersey. Lust writes,

The “Yungborn” is a Garden of Eden, and the only one in America is the Butler “Yungborn”; although I know it is not perfect in every detail, however, I have taken along a good deal of wisdom from Adolf Just, and next summer those who visit our “Yungborn” will experience some of it.”

(Lust, 1908, p.123)

The time spent with Just was very fulfilling for Lust. He exclaims, “I have learned more and taken away more encouragement from this place than from any other, and I think as we Americans usually want the best there is, we should take him [Just] as our model and pattern our institutions after his.” (Lust, 1908, p.123) Lust continues, “I have attended Adolf Just’s lectures and I must say, although we were friends before, our friendship was cemented and fastened; the whole Just family with his brother and children were a great pleasure to me.” (Lust, 1908, p.123) These testimonials from Benedict Lust help us to understand why he steadfastly promoted and advanced The Return to Nature throughout his 50 years of publishing.

Stops in England

Lust ended his Europe trip in England by visiting Richard Metcalfe, of the Priessnitz Hydro at Richmond Hill in Surrey. Lust notes, “Mr. Metcalfe is over eighty years young and works hard every day, as all men should in their early prime.” (Lust, 1908, p.16) Metcalfe had written an important biography on Vincent Priessnitz, entitled, The Life and Works of Vincent Priessnitz, Founder of Hydropathy (1898), and established a magnificent hydrotherapy clinic that commanded “a sumptuous view of the Thames Valley, the Kew Gardens, the Public Park, and the royal estates and game preserves.” (Lust, 1908, p.16) Visiting England was not Lust’s first time there, since he had spent some time in London prior to immigrating to America in 1892. Certainly, Lust would have recollected London weather.

England’s winters are mild and tame in comparison with the snow that is common to NYC in winter. We glean from Lust’s writings that he took lots of notes. He clearly had the redesigning of his own Yungborn in Butler, New Jersey, in mind. Each visit that he makes on his “Sanitarium Tour” was an opportunity to accumulate ideas and details for his and Louisa’s own Yungborn, back home in Butler. Each European sanitarium offered a wealth of ideas for his and Louisa’s own paradise. He remarks throughout his reflections during the journey about what might be possible and what needed to change in his and his wife’s own health retreat center. After visiting Metcalfe’s venue, for example, he comments about the need to expand the season at the Butler Yungborn for more continuous and even constant use by its visitors. He remarks, “We are so crowded now in the summer time that even the space for tents gives out.” (Lust, 1908, p.17) He continues, “The Metcalfe institution has its ample sun parlors for winter enjoyment, its dainty bathrooms, well ventilated and scientifically fitted up its beautiful accommodations.” (Lust, 1908, p.17) We can only surmise that Benedict Lust, ever the student of excellence and models of success, returned to Butler, New Jersey, and began the expansion of its facilities to include sun rooms for his guests to enjoy during the cold winter months.

Metcalfe was an avid follower of Vincent Priessnitz, employing his water therapies as his principle modality, but he also included “herb[s], brine, cabinet Turkish [baths] and sometimes medicated baths, massage, packs, mechanical and gymnastic movements, diet and skilled nursing.” (Lust, 1908, p.17) The literature indicates that many kinds of so-called hopeless cases found their way to Metcalfe’s clinic. Indeed, just as today, naturopaths are often the last resort for patients desperate to heal. Lust recounts,

A peculiar feature of the Metcalfe regime is its provision for incurable cases. Many of the English Hydros entertain a large number of neutral invalids―people not well enough to be home and not sick enough to exert themselves in any direction. Not so here―the majority of Mr. Metcalfe’s patients are sent, or literally carried, at the order of their physician, who resigns them as hopeless.

(Lust, 1908, p.17)

Metcalfe’s success in these incurable cases, Lust noted, were attributable to his somewhat conservative use of Priessnitz hydrotherapies.

While in London, Lust also visited several other notable colleagues in the natural health field, including “Eustace Miles, champion all round athlete and apostle of food reform.” (Lust, 1908, p.17) Food reform in that period invariably meant vegetarianism. Miles offered daily lectures on diverse health subjects, a cooking school, an Esperanto class and, with special attention, provided vegetarian meals.

Next on Lust’s tour were Mr and Mrs C. Leigh Hunt Wallace at 465 Battersea Park Road, London, SW, where they operated “the finest bakery in the world.” (Lust, 1908, p.18) Mrs Hunt Wallace herself was, in Lust’s account, the center of activity of the bakery. She eventually went on to contribute several articles that Lust published over the years in his own journals. Lust pays her a huge compliment and cites one of her articles, “Rules for the Maintenance of Health, which expresses Naturopathic belief more fully than anything else I ever saw in print.” (Lust, 1908, p.18)

Another practitioner and author in England whom Lust believed deserved respect was “Dr. W. MacGregor Reid, editor of The Nature Cure, a magazine which might well be called the ‘English’ Naturopath.” (Lust, 1908, p.18) Lust extols Reid’s efforts as an editor and progenitor of natural healing in England. He cites Reid’s accomplishments: “Dr. Reid has established a magazine, published a number of books, founded various societies, traveled and lectured extensively, done more splendid things than we could enumerate.” (Lust, 1908, p.18) Lust’s trip to England is perhaps best summarized in his comment about his British colleagues, that he experienced and valued their “thoroughness, patience, optimism, non-interference, singleness of purpose, artistic appeal, and sympathetic touch.” (Lust, 1908, p.19-20)

During his time in England, Lust noted the strength of the “Physical Culture movement,” observing the widespread distribution of Bernarr Macfadden’s magazines at the news stands. Back home in New York, Benedict owned and operated a health food store, one of the earliest in the city’s history, which Macfadden often visited. There was a close relationship between these 2 men as they forged ahead in building their respective publishing enterprises in the name of health. For a period of time, Macfadden expanded his publications to England, where he was well received and prospered. Lust has the highest regard for the man who was the leader of Physical Culture, commenting, “Personally we consider Bernarr Macfadden the most effective pioneer for Health that ever lived on this earth, and the debt of gratitude Naturopaths owe him can be discharged in no adequate manner save by honest and enthusiastic recognition of his work.” (Lust, 1908, p.19)

Lust’s Reflections – a New Perspective on America

Upon his return to America and his home, Lust reflected on his experiences in Europe and his visits to its great sanitariums. He comments, “I have learned a good deal and I must say a good many of the naturopathic practitioners from Europe can learn a good deal from us.” (Lust, 1908, p.124) He was not entirely convinced, though, that these prestigious watering holes were all that they were cracked up to be. He notes, “Some institutions seem to me like a reformatory or prison; and some of the Naturopaths put themselves too high on the pedestal.” (Lust, 1908, p.124) His final conclusion was prophetic in many ways, when he envisioned America surpassing one day the German Natural Health movement. Lust declares, “I think America one day will lead the world in the healing art. Things will be done on a larger scale here than elsewhere as soon as we get proper legislation; America will go ahead very rapidly and be an example to other nations.” (Lust, 1908, p.124)

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References:

- Lust, B. (1908). The editor in Europe I. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX (1), 16-20.

- Lust, B. (1908). The editor in Europe II. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX (2), 52-56.

- Lust, B. (1908). The editor in Europe III. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX (4), 116-124.

- Lust, B. (1918). Great pioneers. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXIII (5), 446-447.