Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

Nature Cure Clinical Pearls

[Nature’s] ways are so simple and harmonious, that people are confounded by her very simplicity. Besides, her remedies do not cost enough money to make sufficient impression upon the minds of the ignorant (?) intellectuals. Ludwig Staden, 1900, p.126

I repeat, the duration of the half-bath should never exceed from two to six seconds. Sebastian Kneipp, 1901, p.14

The true Naturopath will always treat individually; he is treating the person, not the case. Each person is differently constituted, consequently every case must be different. Ludwig Staden, 1902, p.15

In 1896 the world of publishing was an entirely new adventure to the young Benedict Lust. At only 24 years of age he began his first magazine, Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter, as a promise to Father Sebastian Kneipp to raise awareness of water cure in America. His first foray into the American serial publication scene was mostly a German bimonthly (and eventually monthly) issue on water cure as defined by Kneipp. The articles in Lust’s early publications were either excerpts from Kneipp’s books or from other German authors writing about Kneipp water cure, with occasional English translations from Kneippian books. As the name of his magazine indicated, Kneipp’s name and water cure therapies were exclusively targeted to an audience composed of German immigrants who would be very familiar with Kneipp’s contribution to health and hydrotherapy.

By 1900 Benedict Lust had had 5 years under his belt of producing his magazine in New York City. With each passing year the issues increased in volume, source of content, advertisements, and distribution. In 1900, though, Lust not only changed the name of Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter to The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, but also switched to English in his efforts to educate an uninformed American public with little knowledge of Kneipp’s work. Lust’s top priority was to spread the work of Kneipp’s water cure and therapies. In the masthead of the January issue, 1900 (Figure 1), Lust writes, “A Magazine devoted to the late Reverend Father Kneipp’s Method and kindred Natural Systems.” (Lust, 1900, p.1) The cost for a single copy was 10 cents, and for a year’s subscription, $1.00. This new English publication had a larger market to reach and serve within New York City and beyond, from his publishing headquarters at 111 E. 59th Street. He had also diversified by opening up a “Kneipp Health Store” that sold every conceivable item associated with Kneipp, including herbal teas and pills, food items, healthy underwear, garments and shoes, and books.

Figure 1. Kneipp Water Cure Monthly Masthead

Kneipp’s own writings essentially formed the foundation for Lust’s magazine, especially in the beginning. It is interesting to witness the changes that took place in Lust’s publications as his horizons widened. In 1900, Lust’s little publication attracted many more people who had common interests. Soon, the number of Kneipp excerpts and articles that first dominated declined, and other writers and therapies other than water cure were soon added to the pages. Lust, himself, contributed more articles written in English, and dialogues formed between readers and those aligned with the vision of natural healing as espoused by Lust.

The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly was a growing concern. Like a train leaving the station, people wanted to be on board. Supporters, such as Mr Peter Semler of 64 Franklin Street, Jersey City Heights, NJ, opened up a branch office for Lust’s publication. (Lust, 1900, p.187) Semler’s office enabled more people to access the publication and also to further the spread of Kneipp therapies elsewhere. Lust continued to form similar relationships with others to increase the distribution of his publications.

Ludwig Staden

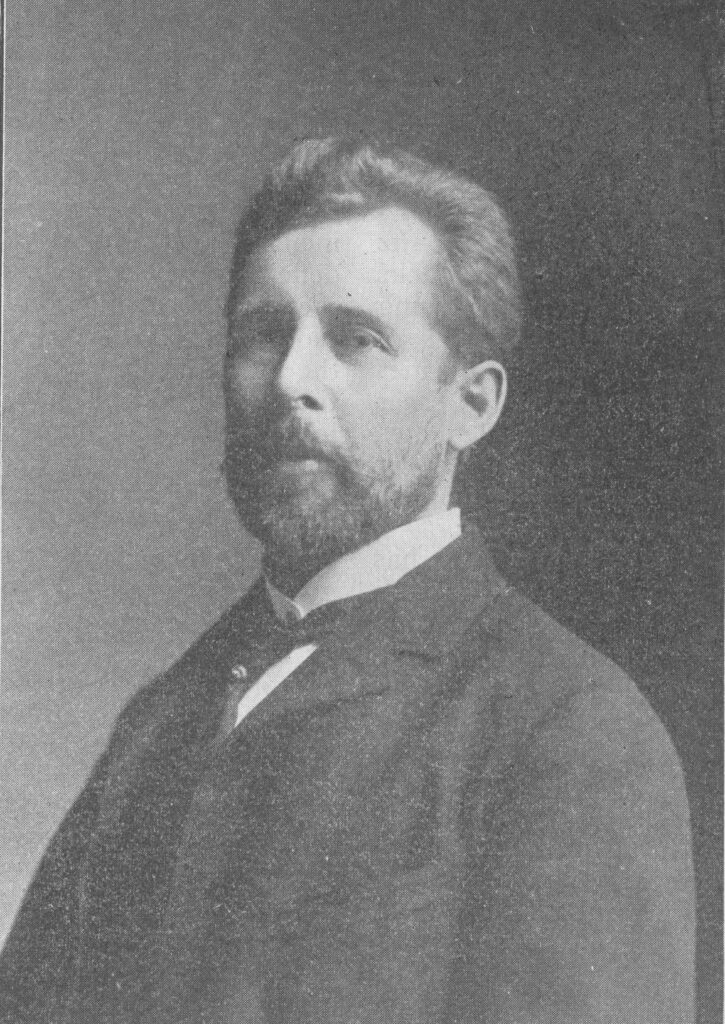

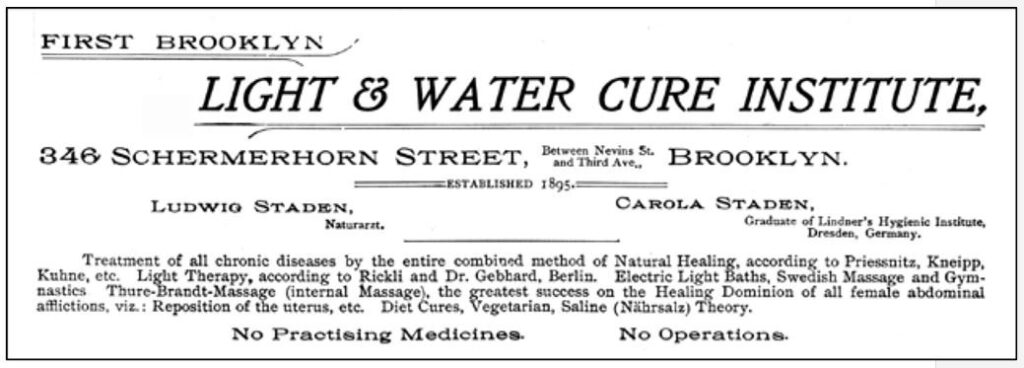

Ludwig Staden (Figure 2) called himself a “Naturarzt” and also referred to himself as a Hygienic Physician. As an early adapter, he already subscribed to natural healing and water cure when Lust began his publications. In an early advertisement that Staden placed in The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, he states that his clinic was Brooklyn’s first “Light & Water Cure Institute” (Figure 3). Located at 346 Schermerhorn Street, Brooklyn, NY, Ludwig Staden practiced with his wife, Carola, a practitioner of the Thure-Brandt massage for women.

Figure 2. Ludwig Staden; 1902

Figure 3. Light & Water Cure Institute

Figure 3. Light & Water Cure Institute

The Stadens had an eclectic practice that incorporated water therapies from Vincent Priessnitz and Sebastian Kneipp, as well as the steam and friction hip baths of Louis Kuhne, the air cure of Arnold Rikli, physical culture fostered by Bernarr Macfadden, Swedish massage, and vegetarianism. Ludwig and Carola both contributed writings to Lust’s magazine. Carola focused on women’s health and gynecology, and Ludwig became a monthly contributor for a column, “Hydropathic Medical Adviser” that provided free health advice to the subscribers of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly.

Bilz’s Natural Method of Healing

In the description of his column, Staden indicates that the free advice is offered following “the rules of the Natural Method of Healing.” (Staden, 1900, p.14) Staden’s reference to “Natural Method of Healing” was an explicit declaration that he was adhering to the Kneippian principles and therapies, recorded at the time in a colossal 2-volume set that was also called Natural Method of Healing (1898), written by Friedrich Eduard Bilz.* Bilz’ encyclopedic account of Kneipp’s water cure became a reference guide or textbook for the early practitioners of water cure. In his books, Bilz elaborated, in greater detail than Kneipp himself had, on each of the water therapies used in a water-cure sanitarium, and provided treatment protocols for every conceivable disease of his day.

In his first chapter, Bilz provides an introduction to the natural method of healing and includes 26 rules, or principles. The first and probably most important rule is that water applications are only carried out if the patient is warm. I have numbered and summarized these rules as follows (Bilz, 1898, p.1-6):

- Before water applications, the patient is warm.

- Compresses can be applied before bed.

- Treatment rooms should be warm.

- No water treatments shortly before or after meals.

- No treatments after unusual excitement or exercise that puts the blood in motion. The patient should be tranquil before a water treatment.

- Exercise, hot water bottle, friction, and bed rest after water treatment restore warmth to the patient.

- A cold water treatment is given after all warm water applications.

- The body must recover its warmth before administering a second water treatment.

- Sips of water during treatments are advised.

- Sick patients should abstain from a stimulating diet.

- Care and cleanliness applies to materials and methodologies used by those attending patients.

- The sick room has ample fresh air so that patients can rest.

- Never wake a patient during a treatment.

- Weak patients should receive mild baths (92° to 94° F/33° to 34° C).

- Patients capable of enduring cold water applications produce reactions; for example, reddening of the skin.

- Warm water applications above 100° F/38° C are rarely recommended.

- Patients receiving foot or hip baths should not read during the treatment.

- Symptoms of an illness can occur consecutively or concurrently.

- Cheerfulness is an important factor in healing.

- If cure does not come quickly, proceed slowly.

- Do not plunge into treatment.

- Do not be harsh with children adverse to cold water.

- Use warmer water (2° to 4° F/1° to 2° C warmer than normal) for enfeebled patients.

- Taking medications concurrently with water therapies impedes results.

- Review the chapter on fever in Bilz’s book, The Natural Method of Healing.

- Review the treatments for each disease condition that are listed in Bilz’s book.

Bilz cautions that “small efforts of water applications” often produce the best and greatest outcomes. He reminds us of the true healer: “It is Nature that cures, not we.” (Bilz, 1898, p.6)

Hydropathic Medical Advice For FREE

Each month in 1900, Staden answered letters sent to The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly in his column, “Hydropathic Medical Advisor.” His answers provide clarity and enlighten us as to how the early Kneippians and water-curists treated different diseases. The above list of Bilz’ guidelines for water cure gives us a fair idea of the important considerations that Kneipp used for the treatment of different diseases. However, what is missing, that we cannot read in between the lines, is how to determine why one water application was chosen over another. Another confounding factor is that one practitioner used one methodology while other water therapists used another. Even so, Staden’s treatment plans generated for the readership of Lust’s publications reliable insight into a pattern or a logical rationale for his clinical decisions.

The breadth of problems fielded by Staden spanned every bodily system. For example, he received inquiries regarding asthma, headaches, chronic nasal catarrh, bladder spasms, hemorrhoids, eye symptoms, epilepsy, mumps, chronic cold feet, uterine cancer, amenorrhea, lupus (skin), hay fever, mercury toxicity, dyspepsia, constipation, nervousness, etc. When receiving a complicated case, Staden did not hesitate to refer the person to seek personal care with qualified practitioners.

To Lillian S. of Washington, who suffered from epilepsy, Staden writes, “I would recommend to you a course of treatments in a good water institution; there you [can easily] learn how to treat yourself later at home without fearing to make a mistake.” (Staden, 1900, p.46) To Katie F., of St Andrews, Canada, Staden writes, “The best advice I can give you is to go into a Sanitarium of our method, for instance, Dr. Strueh’s at Belden Avenue, Chicago or Dr. Kellogg’s at Battle Creek.” (Staden, 1900, p.210) Although he refers these women to seek help, he also provides some suggestions on diet and water applications.

Staden was prolific. The brief scope of this article, alas, dictates representative cases from among the myriad letters and conditions that Staden addressed. Let us consider 3 respiratory conditions as cases in point: asthma, chronic nasal catarrh, and hay fever. We will notice that there are common prescriptions, and also individualized as well as specific instructions.

Asthma

In January’s issue, Mr G. M. of Scranton, PA, writes for help for asthma. In response to Mr Scranton’s initial letter, Staden’s suggestions are comprehensive. He begins by outlining for his patient a process for water-cure hardening, leaving no stone unturned. The concept of hardening was first introduced by Vincent Priessnitz, who used cold water applications to strengthen the body against disease and boost the immune system.

It is indeed intriguing to learn how Staden instructed the patient in the hardening process. Each morning the prescription entails a cold sponge bath followed by a friction rub. The patient returns to bed for 10 to 15 minutes to warm up. During the week, 3 to 4 bed steam baths are recommended, with emphasis on using 3 hot water bottles for the feet, calves and thighs; and 3 times a week, alternate foot baths are taken. The alternate foot bath is in tubs of hot water 1 foot deep, with water temperatures of 100° to 105° F/38° to 40.6° C for 5 minutes and alternated with a cold foot bath for a half-minute in water that is 60° F/15.6° C.

Bed Steam Bath Directions

The bed steam bath was a common treatment given by Staden in the hardening process. Ironically, the name of this water application is quite misleading. We think that steam is being used in bed, and that is far from the truth. In another issue, Staden is asked to describe how to administer a bed steam bath. He answers:

The bed steam bath is a three-quarter or full pack with one hot bottle (if possible, stone bottle wrapped in a wet towel applied to the feet, two of such bottles outside to the calves, and two bottles to the thighs. First, the body has to be wrapped in a wet sheet, then the hot bottles have to be placed, then the woolen blanket has to be enveloped round the whole. Three hot bottles on average are sufficient. Duration of the bed steam bath is from one to three hours. (Staden, 1901, p.228)

Kneipp’s signature water treatment was the “gush.” Staden tells the patient to begin on the first day with a knee gush or douche; on the second, the upper douche; and the third day, the back douche. Kneipp originally used a simple garden watering can, and preferred it to the use of a hose. For example, a knee gush is the “application of cold flowing water from the kneecap to the feet, applied in such a manner as to form a flowing sheet of water over the whole lower leg.” (Baumgarten, 1904, p.7) The upper douche covered the chest, upper back, and arms, and the back douche was specific for the back and spine.

An advertisement Staden placed in The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly indicated that he also utilized coaching and mentoring in vegetarianism in his practice. He suggests a vegetarian diet, avoiding stimulating drinks and foods. He also prescribed plantain tea, sleeping with an open window, and breathing through the nose rather than the mouth. (Staden, 1900, p.14)

This extensive treatment plan for this asthmatic patient was to assist in eliminating the cause of asthma: the accumulation of morbid matter in the blood and the muscular fibers of the trachea.

Chronic Nasal Catarrh

For Mrs B. L., of Baltimore, MD, the problem of chronic nasal catarrh was attributed to an enduring head cold. Like in the case of asthma, Mrs B. L. was instructed to take a bed steam bath for 1½ to 2 hours in duration, followed by a cool sponge bath. However, she was to take these every day. Every morning, a good friction rub with a wet towel, and every evening, a throat compress and an abdominal bandage were prescribed. (Staden, 1900, p.31) The difference between an abdominal bandage and an abdominal compress is that a bandage involves wrapping around the body, while “compresses are merely poultices of coarse linen folded to several thicknesses, dipped into warm or cold water, well wrung and laid directly over the suffering parts, being covered with a woolen cloth.” (Lust, 1903, p.318) The abdominal “bandage covers from the pit of the stomach to the middle of the thigh.” (Kneipp, 1909, p.631)

The “abdominal bandage” was best done at night when patients were in bed, he advised. Bilz labeled the abdominal bandage as “the universal remedy.” (Bilz, 1898, p.1678) This remedy, an exclusively cold water application, was used very frequently for many different conditions by the early Naturopaths.

We are familiar with the contemporary “neti pot” and “nasal lavage,” to which, although not with that terminology, Staden refers when he recommends that “drawing water up the nose and frequent gargling” (Staden, 1900, p.31) would be beneficial. As in the case of asthma, the alternating foot bath was suggested 3 times a week.

Hay Hever

Another reader, Max from New Jersey, writes for help for hay fever. Staden defines hay fever as “catarrh of the bronchial tubes, nose and eyes [which] mostly attacks people who live too luxuriously.” (Staden, 1900, p.127) His first course of action was a simple vegetarian diet and the elimination of alcohol, meat, and spiced foods. The water applications recommended were a bed steam bath for 1 hour, followed by a cool half-bath. A half-bath is taken in an ordinary bath tub “filled with cold water reaching up to the navel.” (Lust, 1903, p.321) Staden advised a sun bath of 15 to 30 minutes’ duration, considering this to be superior and more effective than a bed steam bath. Other water applications included a daily cool sponge bath and enema, and every other night an abdominal bandage. He also suggested gargling 3 or 4 times a day with water mixed with a little bit of lemon juice. Staden reminded his patient, as well, about the importance of sleeping with open windows and using breathing exercises. (Staden, 1900, p.127)

In the next issue, we will explore Ludwig Staden’s suggestions for digestive complaints and expand our repertoire of water-cure applications.

*Bilz’ German book was first published in 1888, and the English version was published a decade later.

References:

Baumgarten, A. (1904). The knee douche. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (1), 7-10.

Bilz, F. E. (1898). The Natural Method of Healing. New York, NY: F. E. Bilz Publishing; Volumes 1 & 2, pp. 2046.

Kneipp, S. (1901). The half bath. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (1), 14-15.

Kneipp, S. (1909). Bandages and compresses. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XIV (10), 624-632.

Lust, B. (1900). Announcement. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (10), 187.

Lust, B. (1903). Means of hardening for children and adults. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, IV (11), 313-322.

Staden, L. (1900). Hydropathic medical adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (1), 14.

Staden, L. (1900). Hydropathic medical adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (2), 31.

Staden, L. (1900). Hydropathic medical adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (3), 46.

Staden, L. (1900). How Nature cures. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (7), 126.

Staden, L. (1900). Hydropathic medical adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (7), 127.

Staden, L. (1900). Hydropathic medical adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (11), 210.

Staden, L. (1901). Naturopathic adviser. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (11), 228.

Staden, L. (1902). What is Naturopathy? The Naturopath and Herald of Health, III (1), 15-118.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_photopiano’>photopiano / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE, a graduate of CCNM, is a licensed ND in Oregon. Sussanna is a frequent presenter, nationally and internationally. As Curator of the Rare Books Collection at NUNM, she is the author of The Hevert Collection, a 12-book series about naturopathic medicine, the ninth volume of which is now complete, Mental Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Sussanna founded The Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopathic doctors to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. Her next large project is to complete the development of her new medical spa in Manitou Beach, Saskatchewan – Manitou Waters Centre. She is the co-founder of the International Congress on Naturopathic Medicine and the inaugural conference chair of the Healing Skies Naturopathic Medicine Conference, in Saskatchewan.

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE, a graduate of CCNM, is a licensed ND in Oregon. Sussanna is a frequent presenter, nationally and internationally. As Curator of the Rare Books Collection at NUNM, she is the author of The Hevert Collection, a 12-book series about naturopathic medicine, the ninth volume of which is now complete, Mental Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Sussanna founded The Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopathic doctors to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. Her next large project is to complete the development of her new medical spa in Manitou Beach, Saskatchewan – Manitou Waters Centre. She is the co-founder of the International Congress on Naturopathic Medicine and the inaugural conference chair of the Healing Skies Naturopathic Medicine Conference, in Saskatchewan.