Nature Cure

Vicki Simkovic, ND

Being in touch with the natural world is crucial.

David Attenborough

Contact with nature has long been recognized as an important agent of healing, yet surprisingly it is often overlooked as a therapeutic option in naturopathic practice. Early nature physicians such as Adolph Just believed that living in direct, intimate contact with nature was the only way to regain a feeling of “health, happiness and joy of life, repose and peace of the soul.”1(p116) Nearly a century ago, biologist Sir Arthur Thompson extended the traditional concept of the vis medicatrix as the innate healing response to mean the external natural environment; he believed that our connection with nature was so firmly rooted in our ancestry that to lose this contact would inevitably have negative consequences on the human psyche.2 Interestingly, though by no means causative, rising trends of mental health disorders in developed nations have coincided with increased reliance on modern technology and have reduced nature-based recreation.2-5 National and state parks in the United States have seen a 25% to 50% decline in visitation in recent decades,2-4 and rates of depression continue to rise. A young adult in North America today has a 1 in 4 chance of depression vs just 1 in 10 two generations ago.5 Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence, including brain imaging data, which support the critical role that exposure to nature has in restoring mental health and physical well-being. In addition, it provides confirmation that ongoing advances in computer technology will not necessarily correlate to a psychologically well-adjusted society.

The Restorative Effects of Nature on Stress Physiology and Mental Fatigue

In the early 1980s, biologists such as Wilson6 and Ulrich7 hypothesized that humans have deeply ingrained, genetic predispositions to tune into aspects of the natural environment and that atonement to these natural features would lead to positive psychophysiological states. Ulrich7 was the first to begin detailed studies by exposing stressed-out undergraduate volunteers, who had just completed an examination, to images of urban or natural landscapes. Those who viewed natural sceneries reported increased positive mental outlook. In a later study, Ulrich et al8 used physiological markers (heart rate, frontalis muscle tension, skin conductance, and pulse transit time) to evaluate stress responses of 120 participants who viewed urban or natural scenes following a stressful video on workplace accidents. Consistent with the predicted model, physiological markers of those who were exposed to natural vs urban landscapes showed a more dramatic and complete recovery to stress, as well as a shift toward a more parasympathetic state. In addition, using electroencephalograms, Ulrich9 found greater alpha wave brain activity when study participants viewed nature scenes (the same waves induced during states of relaxation such as meditation). Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Kim et al10,11 found that, when subjects observed urban scenes, areas of the brain associated with the recall of emotional stress were activated (ie, amygdala); in contrast, natural scenes activated areas associated with increased empathy and emotional stability (ie, anterior cingulate and insula). Despite these positive findings, most studies are limited to simply viewing photographic images. How do the effects differ in real life, in a more complex environment, when all the senses are completely immersed in nature? In Japan, Park et al12 conducted such a study based on the benefits of Shinrin-yoku, which means “forest bathing” (immersing the entire mind-body in nature) and was developed in the 1980s by the Forest Agency of the Japanese Government, who recognized the need to reconnect the populace with nature. When subjects who spent 40 minutes walking in a cedar forest were compared with subjects who walked indoors in a laboratory, those who walked through the cedar forest noted improved energy and mood, lowered cortisol level, and decreased blood pressure and pulse rate, while the laboratory group showed no benefit. Further investigations of Shinrin-yoku have demonstrated that forest environments improve natural killer cell activity and increase the production of anticancer proteins.13 Other research has isolated various senses to compare benefit. For example, in one study,14 olfactory and physiological response to the odor of wood was tested by asking subjects to smell limonene, a phytoncide found in wood and citrus peel, in a concentration of 10 microliters per 30 L. Phytoncides are aromatic substances released by all plant species and vary across landscapes.

The Benefits of Nature for Mental Fatigue

The brain of a modern person living in a highly urbanized environment must be adept at filtering relevant from irrelevant information if it is to survive the overwhelming onslaught of distractions, including (for example) mobile phones, advertisements, social networking sites, societal expectations, and much more. The brain must be able to cope with rapid change. Kaplan15 theorized that this filtering capacity was a limited resource and when depleted would lead to mental fatigue and in turn irritability, anger, increased distractibility, burnout, anxiety, depression, and impulsivity; these are many symptoms associated with “adrenal fatigue” by some NDs.

The attention restoration theory by Kaplan15 hypothesized that the restorative benefits of nature on the brain were based on the ability of natural landscapes to engage the mind within a complex environment, while requiring effortless attention. Further research confirmed the ability of natural landscapes to reduce mental fatigue and improve cognitive function. Berman et al16 found that, when 20 young adults diagnosed with clinical depression walked within a quiet nature setting, they scored better on a series of tests about attention and short-term memory compared with when they walked in a noisy environment. In addition, Berto17 found that participants who had been mentally fatigued from a sustained attention task performed better on a second attention task after viewing photographs of natural scenery compared with viewing geometric images.

Conclusions, Implications, and Future Directions

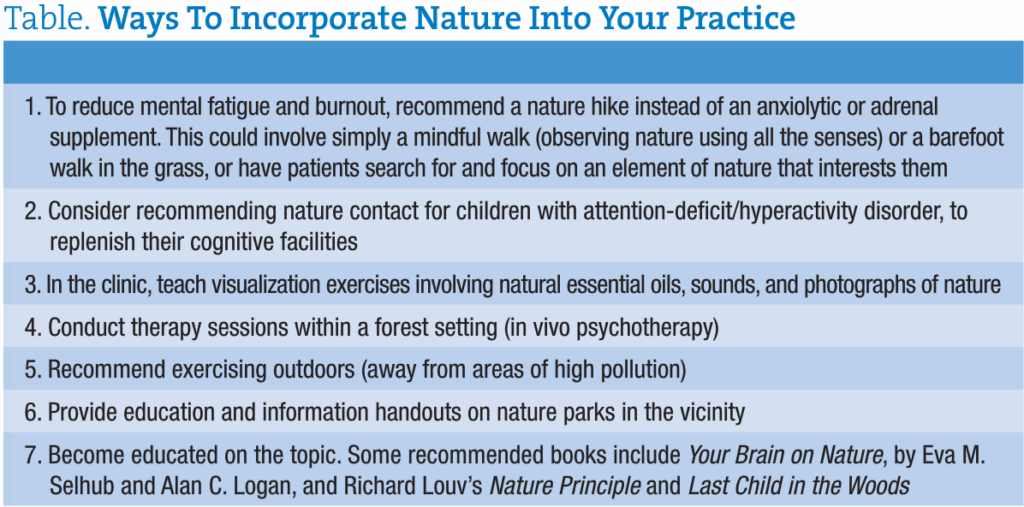

As NDs, we are in an excellent position to become leaders in applying the growing literature on nature contact within a clinical setting. It seems intuitive that nature exposure should go hand in hand with natural therapeutics, and given the ability of nature to normalize physiological markers of stress, reduce mental fatigue, and improve mood, it could become a very useful therapeutic application (Table). There are of course some challenges when applying this to practice. With people more “plugged in” than ever, it can be difficult to motivate people to spend time outdoors. Environmental challenges such as decreased green space (especially in major urban centers) and introduction and spread of invasive species or vectors for disease could make going outdoors rather challenging. For example, fire ants, recently introduced from Europe, have rapidly spread throughout many natural areas within the Greater Toronto Area (Ontario, Canada). They exhibit swarming and stinging behavior when one nears a colony, which could greatly discourage individuals from venturing outdoors. Lyme disease also continues to become a more pertinent reality as it spreads through many naturalized areas in Ontario. It is also important to consider air pollution in highly urbanized areas when recommending outdoor activity. In a recent study18 in Belgium, individuals who lived in cities and exercised outdoors demonstrated higher levels of inflammation and lower scores on cognitive tests compared with those who exercised in a suburban area.

Future research will need to focus on the benefits of nature in more detail. For example, how do the benefits of nature compare across different age groups, cultures, or personality traits? Do those who are naturally inclined to love nature get stronger benefit compared with individuals who are unconnected, and do people who already spend significant amounts of time in nature show increased overall happiness? How strong is the correlation between increased electronic screen time and decreased nature exposure and mental health? What will be the global, long-term implications as natural landscapes continue to dwindle and have less importance in people’s lives? And how does the impact of environmental pollution offset the potential benefits of nature exposure? One thing that remains clear is that, as our technology continues to improve and access to this technology increases, it is important that we never forget our roots as a species. These roots must be firmly grounded within the ecological landscape in which we all belong.

Vicki Simkovic, ND graduated from Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 2011 and is currently in private practice at the Total Health Healing Arts Centre, Newmarket, Ontario. She has a special interest in mental-emotional health, digestive issues, and chronic pain, and she addresses these concerns by incorporating aspects of the natural world, Gestalt therapy, acupuncture, and herbal medicine. In addition, she leads workshops and guided nature hikes on medicinal plants. For more information, visit www.vickisimkovic.com, or e-mail her at vicsim@rogers.com.

Vicki Simkovic, ND graduated from Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 2011 and is currently in private practice at the Total Health Healing Arts Centre, Newmarket, Ontario. She has a special interest in mental-emotional health, digestive issues, and chronic pain, and she addresses these concerns by incorporating aspects of the natural world, Gestalt therapy, acupuncture, and herbal medicine. In addition, she leads workshops and guided nature hikes on medicinal plants. For more information, visit www.vickisimkovic.com, or e-mail her at vicsim@rogers.com.

References

1. Boyle W, Kirchfeld F, eds. Nature Doctors: Pioneers in Naturopathic Medicine. 2nd ed. Portland, OR: NCNM Press; 2005.

2. Logan AC, Selhub EM. Vis medicatrix naturae: does nature “minister to the mind”? Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6(11):1-10.

3. Pergams OR, Zaradic PA. Is love of nature in the US becoming love of electronic media? 16-year downtrend in national park visits explained by watching movies, playing video games, internet use, and oil prices. J Environ Manage. 2006;80(4):387-393.

4. Kareiva P. Ominous trends in nature recreation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7)2295-2300.

5. Logan AC, Selhub EM. Your Brain on Nature: The Science of Nature’s Influence on Your Health, Happiness and Vitality. Mississauga, ON: John Wiley & Sons Canada; 2012.

6. Wilson EO. Biophilia: The Human Bond With Other Species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984.

7. Ulrich RS. Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landscape Res. 1979;4(1):17-19.

8. Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD, Florito E, Miles MA, Zelson M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol. 1991;11(3):201-230.

9. Ulrich RS. Natural versus urban scenes: some psychophysiological effects. Environ Behav. 1981;13(5):523-556.

10. Kim TH, Jeong GW, Baek HS, et al. Human brain activation in response to visual stimulation with rural and urban scenery pictures: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408(12):2600-2607.

11. Kim GW, Joeng GW, Kim TH, et al. Functional neuroanatomy associated with natural and urban scenic views in the human brain: 3.0T functional MR imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11(5):507-513.

12. Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):18-26.

13. Li Q. Effect of forest environments on human natural killer (NK) activity. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(1)(suppl):39S-44S.

14. Tsunetsugu Y, Park BJ, Miyazaki Y. Trends in research related to “Shinrin-yoku” (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing) in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):27-37.

15. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15(3):169-182.

16. Berman MG, Kross E, Krpan KM, et al. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(3):300-305.

17. Berto R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. J Environ Psychol. 2005;25(3):249-259.

18. Giannopoulos A. Urban jogging may be making you dumber. Updated December 9, 2012. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/50109534/ns/health-mens_health/. Accessed January 14, 2013.