Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

These vapors, because they are strongly dissolving and evacuating, make the patient feel easy, comfortable, and most cheerful and happy. Consequently, there is a danger of misusing that which is good in itself, of repeating the vapors too frequently, and by this of doing great harm to the health by imprudence.

-Sebastian Kneipp, 1899, p.17

To extinguish a match, I do not require a smith’s bellows; a soft breath is sufficient.

-Sebastian Kneipp, 1899, p.47

Today there are no really healthy men, we all are more or less filled with morbid matter, our skin is more or less neglected, we all suffer from too much water in our blood and in our system, a steam bath is therefore a necessity to prevent serious sickness.

-Benedict Lust, 1900, p.20

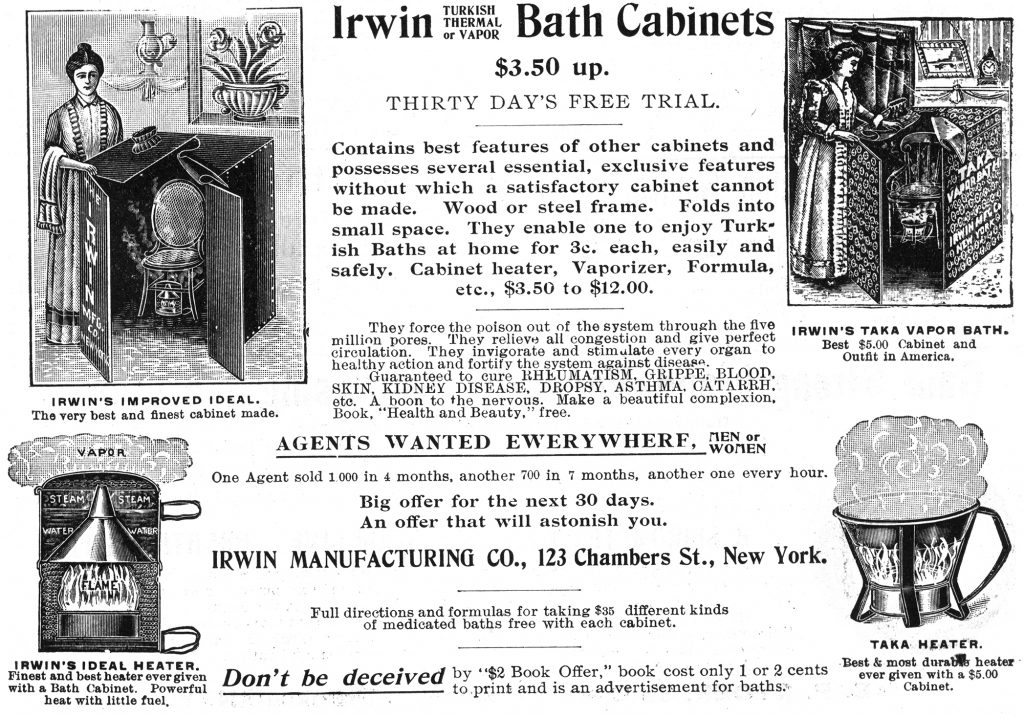

Last month we examined the “steam bath in bed,” and this month we explore Kneipp’s “vapor baths,” referenced above. In pursuit of a curative outcome, Kneipp had used the vapor bath for several years, evolving from his continuous refinements to the implementation of the steam bath. Much like the surge in infrared saunas of today, in the 19th century the Russian steam bath was popular, spawning an industry to accommodate the demand for cabinets for clinics and homes to facilitate these baths. Attractive advertisements began appearing in Lust’s journals, enticing Naturopaths to incorporate the latest steam bath cabinet (Figure 1).n Lust’s first health journal, Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter, published 1896-1899, the prominent language was German, with occasional articles in English, the latter mostly about Father Sebastian Kneipp [1821-1897] water therapies. In a series appearing in several issues in 1899, Kneipp outlined the procedures for “vapor baths.” Kneipp had passed away 2 years earlier; however, Lust had been mandated by the great man shortly before his death in 1896 to spread the word about water-cure therapies. It appears from the available archives that Lust translated lectures and sections from Kneipp’s books and used these in his new publishing endeavors.

These steam cabinets allowed a patient to sit inside and experience a whole body steam bath, except for the head. So effective were these new contraptions that “within a few minutes the whole body [would be] completely enveloped by the hottest vapor.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.16) Kneipp, known for his freezing-cold water applications, had experimented himself with the vapor baths, including the Russian steam bath. His disappointment with the results led him to modify the Russian steam bath according to the same principles that he applied to his water therapies. Kneipp summarized his golden rule for these therapies: “The gentlest application is always the best.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.17) What Kneipp discovered was that when steam baths were delivered to just part of the body, the healing reactions were greater.

Small Is Greater

Kneipp’s insight that partial steam baths were superior motivated him to devise one vapor bath for the head, and another for the feet. He remarks, “All my vapors are in truth only part-vapors, i.e. they act directly on parts of the body only; nevertheless, none of them is without influence on the whole body.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.17) Kneipp recognized that in order to heal the body, one needed to use small measures and, always, gentler forms of therapy. In some ways, Kneipp was modeling the homeopathic small dose in his hydrotherapies. He counsels, “That which cures a sick person, if applied rightly and according to the prescription, may make a healthy person ill if done with negligence and indifference.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.16)

In his view, the attraction of warm hydrotherapies had the danger of both the doctor and the patient relying too much on them, or abusing them with overuse. He advised others when using vapors to exercise caution. Kneipp recognized that the warmth generated during a steam bath functioned to dissolve waste products and toxins. In this regard, ours is an era where hot tubs, saunas, and warm showers constitute the desired temperature of our spa treatments and daily hygiene. Although the vapor bath offered an ideal means to dissolve and mobilize toxins, Kneipp did not abandon his beloved cold-water applications. He states, “I should never use any vapor (to increase the natural warmth for example), where a small water application, a gush or a half bath is sufficient.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.17)

Kneipp iterates that the vapor bath was to be applied “in the gentlest manner and therefore entirely without harm and danger.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.16) In any case, knowing when to prescribe a vapor or steam bath is essential in doing no harm. Those who were least suited to vapors were the patients with “poor blood,” to which patients Kneipp administered very few vapor baths. Instead of vapor treatments, Kneipp would instruct the patient to receive half-baths and gushes. These 2 water applications used cold water temperatures.

Indications

The principle objective by the early Naturopaths was to remove morbid matter from the body. To accomplish this end, Benedict Lust describes the role of steam on skin: “The steam softens the skin, draws the blood to it, and produces sweat by which a lot of morbid matter is secreted.” (Lust, 1900, p.20) Some of the conditions that Kneipp treated using the “Head Vapor Bath” included colds caused by damp exposure or a sudden change of temperature, head disorders, tinnitus, neuralgia of the neck and shoulders, asthma, inflammation of the eyes, and catarrh. (Kneipp, 1899, p.48) Kneipp remarks, “I have applied the head vapor with the best result in cases of congestions or after strokes.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.48)

Louis Kuhne, who had popularized the steam bath with the friction hip bath, also praised the partial steam baths. He extolled the effectiveness of the head vapor bath, writing, “These partial steam baths are of high importance, and afford remarkably quick relief in troubles of the ears, eyes, nose and throat, and particularly in toothache and the treatment of boils and carbuncles.” (Kuhne, 1917, p.362) Lust reiterates Kuhne’s indications and prescribes the head vapor bath for ailments of “ears, eyes, nose, teeth, neck, and for cancers, tumors and exanthema.” (Lust, 1900, p.20) Lust also used the steam bath for insect bites and swelling. (Lust, 1900, p.102)

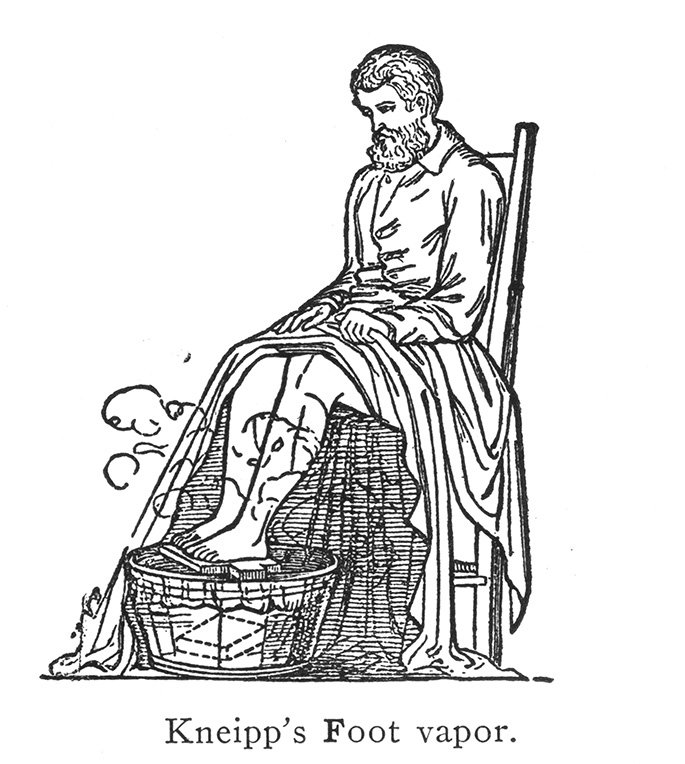

The vapor foot bath (Figure 2) had numerous indications. Kneipp applied the foot baths for those suffering from foot ailments, such as swollen feet, cold feet, and also for abdominal spasms, and headaches originating from blood congestion to the head. (Kneipp, 1899, p.78) Lust combined hayflower decoction with a vapor foot bath for foot cramps. (Lust, 1900, p.102) Today, with so many people glued to their screens for all hours of the day and night, we have created high-wired diseases such as insomnia, anxiety, and headaches. There is something in common between the head congestion that Kneipp talks of and our modern blood congestion to the head from chronic screen-time and late evening and night screen-time. Perhaps the foot vapor bath may help to redistribute the blood for a peaceful night of sleep. In any case, steam or vapor baths had an excellent effect on the skin; however, Lust cautions, “Weak people, patients who are very seriously ill, and very nervous people should not take steam baths, nor do those who easily and freely perspire.” (Lust, 1904, p.85-86)

The vapor foot bath (Figure 2) had numerous indications. Kneipp applied the foot baths for those suffering from foot ailments, such as swollen feet, cold feet, and also for abdominal spasms, and headaches originating from blood congestion to the head. (Kneipp, 1899, p.78) Lust combined hayflower decoction with a vapor foot bath for foot cramps. (Lust, 1900, p.102) Today, with so many people glued to their screens for all hours of the day and night, we have created high-wired diseases such as insomnia, anxiety, and headaches. There is something in common between the head congestion that Kneipp talks of and our modern blood congestion to the head from chronic screen-time and late evening and night screen-time. Perhaps the foot vapor bath may help to redistribute the blood for a peaceful night of sleep. In any case, steam or vapor baths had an excellent effect on the skin; however, Lust cautions, “Weak people, patients who are very seriously ill, and very nervous people should not take steam baths, nor do those who easily and freely perspire.” (Lust, 1904, p.85-86)

The Head Vapor Bath

Equipment and material requirements for the head vapor bath included a tub filled with boiling water, a stool or a table to place the tub on, a chair for the patient, a blanket to cover the patient, and cloths to retain the steam (Figures 3, 4). The tub with the boiling water was immediately covered with a tight-fitting covering, and damp cloths were also used to retain the steam. “The patient has the whole upper part of his/her body bare and dry cloth around the waist to prevent the garments from becoming wet by the perspirations as it flows down.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47)

Lust adds, “the patient is seated on a chair in a way one sits on horseback” (Lust, 1900, p.20), and he provides details about how that patient leans over the tub awaiting the steam bath and is enveloped with the blanket lightly. The key word here is “lightly.” The image of a heavy blanket enveloping a perspiring and hot patient in a steamy milieu suggests potential for some degree of a claustrophobic nightmare. Keep in mind, though, that the blanket is draped in such a way that no steam is allowed to drift out. Once the blanket is in place, the attendant gently removes the coverings from the tub and secures the blanket in place. Kneipp describes the next step: “Then the vapor comes forth like a glowing stream, penetrating the head, chest, back, and to the whole upper body, as it begins its dissolving work.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47)

Another suggestion that Lust provides for the mechanics of a head steam bath is to “take two chairs and put the seats together; sit astride of one of the chairs… and put on the other chair a vessel of boiling water over which the head is held.” (Lust, 1904, p.108) The vapor foot bath, on the other hand, had the patient seated on a chair with his feet resting on a stool that was placed in a tub of boiling water, with the water level below the uppermost surface of the stool. When the patient was ready, a blanket was snuggly placed over the feet and the tub of steaming water.

It’s HOT

If the immediate reaction of a patient in the steam bath is the intensity of heat, Kneipp had a suggestion that worked well. He advises,

At the first shock of the hot clouds, it is well to [have the patient] take a more upright position, to raise the head, to turn to different directions, etc. When the patient is more accustomed to it, and the heat is diminishing, the body returns to its prescribed, bent position. (Kneipp, 1899, p.47)

Another suggestion from Kneipp: “During the whole of this time the patient ought not only to hold his head over the vapor, but also to open his eyes, nose and mouth as much as possible, and let the vapor stream in as much as s/he can bear.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47)

To help the patient endure the head vapor bath, Kneipp used herbs which he mixed into the hot water. Fennel was his favorite. He recommended “one spoonful of ground fennel [to be] sufficient for an application.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47) Then next came sage, yarrow, mint, elder, Equisetum, and linden blossoms. If none of these herbs was available, then nettles or hayflowers were substituted. (Kneipp, 1899, p.47) As mentioned earlier, for the vapor foot bath, Kneipp mixed hayflower decoction into the hot water. (Kneipp, 1899, p.78)

Duration

Kneipp determined that the duration of a head vapor bath should be from 2 to 24 minutes. (Kneipp, 1899, p.47) Lust, on the other hand, prescribed head steam baths for 20 to 40 minutes. (Lust, 1904, p.108) The consequence of too-frequently-used head vapors was that such overuse could result in debilitating weakness. So, Kneipp advised that “two a week should not be exceeded.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.48)

For the vapor foot bath, the duration suggested was between 15 and 20 minutes. Before the days of electrical convenience, Kneipp did not have at his disposal electrical warming units to keep water hot and steaming. Thus, hot bricks were added to the water to maintain the flow of steam. Today, we have numerous easy and safe devices at our disposal to keep water hot and steaming.

Perspiration

The vapor bath worked very quickly, causing perspiration to appear almost immediately. Kneipp recounts, “With most persons the drops of sweat begin rolling down the forehead after the first five minutes; but after eight or ten minutes, they come forth from all the pores.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47)

After the Bath

Like other hydrotherapies, both the head and the foot vapor bath ended with a cold water application. Kneipp adds these cautionary words: “The patient should not venture to go into the open air, without a previous cool ablution, by which the pores opened by the vapor are closed again.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47) For weak patients, a simple wash with cold water and a towel sufficed, but for others after the head vapor bath, “the upper gush is given by slowly pouring one or two watering cans of cold water over the vapored parts, with the exception of the head.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.47) After the cold water gush, the hair and face were dried with a towel and the patient was instructed to quickly put on his/her clothing without drying with a towel. Further, Kneipp advises that “exercise is to be taken either by walking or working, until the body is entirely dry and [warm].” (Kneipp, 1899, p.48) After the head vapor bath, Lust recommended as well “a sitting bath, or short bandage, leg packs, walking barefooted or a foot bath.” (Lust, 1900, p.20)

For the vapor foot bath, cold water applications always followed, to the parts of the body that had been exposed to the steam bath. Kneipp describes in detail this process:

If only the feet and legs as far as the knees are sweating, a quick cold ablution with a towel will suffice; stronger persons may take a knee gush. If the thighs and the abdomen are in perspiration, a half bath is sufficient; but if the whole body is seized with perspiration, then the whole body must also be cooled, either by a half bath with washing off the upper body, or by a full bath or full ablution. (Kneipp, 1899, p.78)

Closing Comments

The simple elegance of these protocols is matched by their unrelenting effectiveness. That the early Naturopaths relied heavily on water in various manifestations is testament to their principles-driven and experience-driven medicine. Invariably committed to do no harm, they were exceptionally skilled at developing techniques using the basic elements of air, earth, and water, which they consistently refined and perfected for their patients and colleagues.

In the spirit of Kneipp and Lust, Dr Cathy Rogers of Washington is widely known for her present-day, inventive, even brilliant interplay of creative, simple equipment constructions and masterful processes to mimic a steam bath. She uses bamboo rods attached to the chair of the patient to suspend the blanket so that it does not touch the patient and interfere with the steam bath. The remarkable tools and practices of our forebears live on.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References

- Kneipp, S. (1899). Water applications. Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter, IV (1), 16-17.

- Kneipp, S. (1899). Water applications, (continuation). Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter, IV (2), 47-48.

- Kneipp, S. (1899). Water applications, (continuation). Amerikanischen Kneipp Blätter, IV (3), 78-79.

- Lust, B. (1900). The steam bath and its usefulness. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (2), 20.

- Lust, B. (1900). Special vapor application. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (6), 102.

- Lust, B. (1904). Naturopathy VII. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (4), 84-87.

- Lust, B. (1904). Naturopathy VIII. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (4), 108-109.

- Kuhne, L. (1917). My remedial agents. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXII (6), 359-368.