Jon Wardle, ND, PhD, MPH, LLM

Naturopathic News

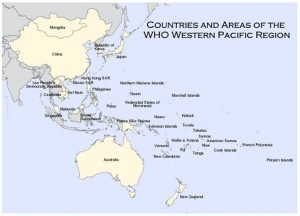

While the World Health Organization (WHO) maintains a truly global focus, much of its practical work is conducted in its regional offices. One of those offices is the Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO), headquartered in Manila, in the Philippines. The WPRO consists of 37 country members (see Figure 1). As occurs in other WHO regions, representation at a regional level is open to autonomous territories, whereas only full countries can maintain WHO membership. As such, membership of WPRO also includes the Chinese special autonomous regions (Hong Kong and Macau), the French Pacific island territories (French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna), the US Pacific territories (American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Marianas), and the British dependency of the Pitcairn Islands. The region is geographically disparate, including the Pacific Islands communities, Australasia, most of South-East Asia (except Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand) as well as China, Korea, the Philippines, and Japan. The absence of Indonesia (which is located in WHO’s [South-East Asia Regional Office] SEARO region) physically separates the Southern and Northern countries of this region.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) maintains a truly global focus, much of its practical work is conducted in its regional offices. One of those offices is the Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO), headquartered in Manila, in the Philippines. The WPRO consists of 37 country members (see Figure 1). As occurs in other WHO regions, representation at a regional level is open to autonomous territories, whereas only full countries can maintain WHO membership. As such, membership of WPRO also includes the Chinese special autonomous regions (Hong Kong and Macau), the French Pacific island territories (French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna), the US Pacific territories (American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Marianas), and the British dependency of the Pitcairn Islands. The region is geographically disparate, including the Pacific Islands communities, Australasia, most of South-East Asia (except Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand) as well as China, Korea, the Philippines, and Japan. The absence of Indonesia (which is located in WHO’s [South-East Asia Regional Office] SEARO region) physically separates the Southern and Northern countries of this region.

Figure 1. Western Pacific Region

(Source: World Health Organization)

Naturopathic Presence in the Region

The World Naturopathic Federation (WNF) has 3 full members representing practitioners in 3 WPRO countries – Australia, Hong Kong, and New Zealand. In general, naturopathic practitioners in the region follow a similar practice model (with a broad therapeutic scope) to that of naturopathic doctors in North America, which has been the primary contemporary influence on practice (though WPRO practitioners may have more educational emphasis on ingestible medicines and less on physical therapy compared to their North American counterparts). Australia and New Zealand are undoubtedly the powerhouses of naturopathic practitioner representation in the WPRO region – representing over 90% of the estimated 10 000 naturopathic practitioners in the region, as well as the majority of the profession’s historical presence – with the profession only beginning to emerge in many of the other countries of the region. Small (often solo-member) naturopathic practitioner associations have been identified in a number of countries – Japan, Malaysia, and the Philippines – though have not regularly interacted with the broader (or even regional) naturopathic community. In some of these emerging nations (eg, Malaysia) the government has announced its intention to regulate and develop naturopathic education in that country,1 even though the relatively small size of the profession in that country has not made it a priority.

The emerging nature of the profession in much of the region means that naturopathic graduates practicing in many WPRO countries have been trained outside of those countries (Australia and North America seem to be the major source of practitioners). There have been some attempts to develop local training institutions (most notably at several institutions in the Philippines), and the first intake of students into the new naturopathic program (modeled on North American and Australasian curriculum) at Thailand’s Surin Rajabhat University2 in 2014 may change this intake (Thailand is in the WHO SEARO region, but is the closest university program to many countries within WPRO). In many of these countries strong indigenous traditional medicine cultures make it difficult for other medical systems to make traction. For example, professional associations are prohibited in China unless sanctioned by the government, but strong support for Traditional Chinese Medicine in that country has made it difficult for other medical professions such as chiropractic or naturopathic medicine to gain anything more than a tokenistic foothold.

In other WPRO countries a small naturopathic practitioner workforce exists but remains unorganized. For example, Singapore – like Hong Kong – has a nascent naturopathic practitioner community largely made up of North American and Australian naturopathic graduates due to its permissive immigration policies. Unlike Hong Kong, however, the Singaporean naturopathic community has not coalesced around a single professional association. In some countries, legal recognition of naturopathic medicine has come prior to the presence of an established local practitioner workforce. For example, in the Pacific Islands nation of Vanuatu, an Australian naturopathic graduate (Dr Alan Profke) has been granted recognition as a registered primary care provider in his Paradise Clinic, which provides care to the residents of Aore Island.3 While initiatives such as these are essential to expand the profession into new areas, they do not create a sustainable profession, and more efforts are needed to ensure that local naturopathic capacity is also developed so that countries are not reliant on overseas practitioners.

History of Naturopathic Medicine in WPRO

The precise history of the development of the naturopathic profession in the WPRO region is difficult to ascertain. From its outset, naturopathy was an international profession. The American Naturopathic Association had identified naturopathic doctors in 20 countries in 1918, with international practitioners listed (and some contributing to) Lust’s Universal Naturopathic Encyclopedia Directory.4 In addition to the United States (the home country of the publication), this list included naturopathic practitioners in Australia, Fiji, Japan, New Zealand, and the Philippines. The preponderance of European names in that list of practitioners – both from the Continent and the British Isles – suggests that naturopathic practice entered the WPRO region from both North America and Europe simultaneously.

Then – as now – the Australian contingent of naturopathic practitioners was dominant (representing more than half of all listed practitioners in the region). There again the development of the profession appears to have been influenced early on by both European and North American developments. The first named naturopathic doctor in Australia was German immigrant (and student of Kniepp) Benno Hermann von Koenigswerder, who advertised his lectures from 1903 and practiced in Melbourne and later in Brisbane (see Figure 2). However, many other newspaper articles referenced early Indian naturopathic developments (usually based on British training) as well North American developments. For example, newspapers began quoting North American naturopathic journals as sources in health stories; an article by Dr Erieg from the Naturopath and Herald of Health was cited in a story on overeating and mental acuity in Toowoomba’s Darling Downs Gazette.5

Figure 2. Newspaper Mention of Benno Hermann, 1903

The first specific naturopathic reference in Australian newspapers was published in The Age (Melbourne) on May 16, 1903.

Australia is also the country where most historical records exist, and the naturopathic community appears to have been politically active early on. Lust, himself, spoke positively of legislative and professional developments in Australia, stating in the Universal Encyclopedia that “we look to Australia to inaugurate legislation to make poisoning the sick with drugs a penal offence.” However, the extent to which the history of naturopathy in the WPRO region (or even its most studied nation, Australia) has been studied is dwarfed by the scholarship that has been extended to the profession in North America and Europe. In Australia, for example, some academics have incorrectly assumed the profession was largely absent from early Australian history, and its entrenchment was really only spurred by the growth of the counter-cultural and natural healthcare movements of the 1960s and 1970s.6 Others have conflated the history of naturopathy with Western herbal medicine in Australia, and have viewed naturopathy as a subset of the herbalism tradition in Australia, or have confused the longstanding system of naturopathic medicine with the more recently emerged “natural medicine” movements.7 However, the presence of the profession in WPRO is longstanding.

The earliest Australian newspaper mentions of naturopathy as a specific form of medicine date back to 1903, and they highlight both the early entry of naturopathic medicine in Australia and the various international influences that helped to establish the medical system. Multiple newspaper entries of “naturopathy” occurred during 1903, and can lay claim to being the first specific and official mention of naturopathic medicine in Australia. However, it should be noted that references to core naturopathic modalities such as “nature cure,” “water cure,” and various elements of homeopathic, herbal, and dietetic medicine can be found much earlier – and the controversial question of the provenance of naturopathic medicine as an evolution of the Eclectic medical tradition may also mean that some earlier naturopaths may have categorized themselves as other therapists. The first mention of naturopathic medicine was a health column published in the Toowoomba-based Darling Downs Gazette, authored by an anonymous naturopath (signed off as “The Naturopath”) on the importance of sleep and exercise as a restorative agent for health.8 These were followed up that year by advertisements for individual practitioners in newspapers Brisbane (Queensland), Melbourne (Victoria), and Lismore and Armidale (New South Wales).

Despite often incurring the wrath of the medical profession, it appears that naturopaths did enjoy broad support and recognition from the public, albeit somewhat hampered by their small professional stature. Dr von Koenigswerder’s position as a naturopathic physician in Brisbane was considered sufficient to draw on his expertise as an expert witness in several Court cases in the Queensland legal system.9 In 1905 the Victorian village of Mansfield advertised its attraction of naturopathic services as a sign of its progress.10 Maurice Blackmore – one of Australia’s most well-known naturopaths and founder of what is now Australia’s largest pharmaceutical company (which although classified as being part of the pharmaceutical sector, actually solely produces natural medicines) – was often the subject of attacks of the medical profession, which often sent investigators from the Medical Board of Queensland to charge him with practicing medicine without a license. After one such instance in 1951, the Queensland Parliament debated the veracity of Blackmore’s practice and whether such actions were appropriate. In addition to noting the large number of testimonials to Blackmore’s treatment from patients, Blackmore was also enthusiastically defended by 3 future Queensland Premiers.11 This reflects the contemporary scenario, whereby, despite lack of integration and recognition by government, naturopathic medicine remains enthusiastically supported by the public. In Australia, for instance, studies suggest that approximately 10% of the population regularly use a naturopath,12 with one-third of patients using their naturopathic provider as their primary care provider.13 Naturopathic medicine is also the primary complementary medicine discipline in New Zealand.

Professional Naturopathic Development in the WPRO

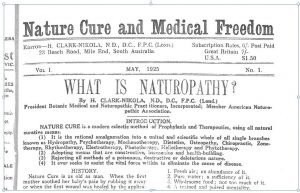

Naturopathic development in the WPRO region occurred early. The Australian WNF member celebrates its centenary in 2019, when it will host the WNF Annual General Meeting. The first association for naturopaths in New Zealand occurred in 1940, when the New Zealand Association of Naturopaths and Osteopaths was formed, an association which still exists (though in a different iteration) to this day.14 In 1925 the South Australian association (the Botanic and Naturopathic Medical Association published the first Australian naturopathic journal, Nature Cure and Medical Freedom. This was followed by the Ivaline Harbinger of Health (1925-1927), Nature’s Path to Health (1930-1950), The Australian Naturopath (1936-1964) in Australia, and Health and Sunshine (1930-1937) in New Zealand. However, beyond Australia and New Zealand, little is known about professional development of the naturopathic profession in other WPRO countries. This is in large part because, although early naturopaths have been identified, much of the profession outside of Australia and New Zealand was lost during the international post-war decline of the naturopathic profession, and has only recently begun to develop again. For example, naturopathy in Hong Kong, the third WNF member, was only reintroduced to that territory 2 decades ago, when an Australian graduate began practicing in that territory.15

Figure 3. Nature Cure and Medical Freedom; 1925

This was the first issue of the first local Australian (and WPRO) naturopathic journal, with ”What is Naturopathy” as the lead article.

Although the naturopathic profession entered the WPRO region relatively early, the development of the profession has not been consistent. Despite early successes, the naturopathic profession in WPRO declined in the period following the Second World War. During the 1960s and 1970s, naturopathy was rejuvenated by the growth of the holistic health movement when, according to Evans, the “new-style flower children” began to join the “old-style straight-backed nature cure adherents.”16 While this undoubtedly rejuvenated the profession in terms of growth in practitioners and public utilization, it also created some dilemmas for the naturopathic profession in the region, as it began to be subsumed into a broader “natural medicine” movement. As naturopathic medicine was the only major complementary medicine discipline not regulated, one of the practical consequences of this was that its associations began to absorb other natural medicine professions that were also experiencing growth as part of the holistic health movement (such as acupuncture and homeopathy). This led to a situation where previously naturopathic associations became broader natural medicine associations (as was the case in Australia, where the National Association of Naturopaths slowly evolved into the Australian Natural Therapists Association),17 or naturopaths began to look towards other discipline associations that aligned with their professional interests better than multi-disciplinary associations (for example, in New Zealand where the New Zealand Association of Medical Herbalists became a natural home for many naturopaths). The lack of a distinct naturopathic voice in WPRO regions is only being remedied recently, in large part due to the catalyst of the formation of the WNF.

Naturopathic Education in WPRO

As in many other regions, early training of naturopathic practitioners focused on clinical apprenticeships and teaching clinics, with training and practice often taking place in institutes of naturopathy that also treated the public.18 This was often borne of necessity, as naturopathic training was not only unable to be accredited in formal education institutions (which were – and remain – largely public government institutions in the WPRO region), but naturopathic medicine itself was often discouraged or, in some cases, even illegal. In an article published in 1938 in Nature’s Path to Health, the content of what such a course may have looked like was described by Frederick Roberts. (This description was followed by an advertisement for Robert’s own college, the British and Australian Institute of Naturopathy.):

The naturopath is a graduate of a naturopathic institution. His preparation for the professional careers as a naturopath consists of a four-year course of study, which includes what are known as the basic sciences. These sciences are: (1) Biology, (2) Chemistry, (3) Bacteriology, (4) Anatomy, (5) Physiology, (6) Embryology and Obstetrics, (7) Pathology, (8) Physical Diagnosis, (9) Psychology, (10) Nature Cure, (11) Hygiene and Sanitation, and other therapeutic subjects such as (1) Mechanotherapy or Physical Manipulation, (2) Hydrotherapy or Water Cure, (3) Electrotherapy, (4) Biochemistry [this was an early term for vitamin and mineral supplementation], (5) Dietetics, etc. The naturopath does not study materia medica or the prescribing of drugs, but he is taught phytotherapy or the use of herbs in the healing of the sick. In addition to the four years study of naturopathy or drugless healing, the naturopathic student spends one or two years at a naturopathic sanitarium or clinic. At the completion of his studies he obtains the degree of N.D. (Doctor of Naturopathy).18

Eventually, naturopathic education began to be brought into the university sector (where possible), and as private institutions began to be allowed to offer accredited degree programs, the standard of education in WPRO has been degree-level. There appears to have been some interaction between the Australian and international naturopathic education sectors. In 1971 it was announced in The Health Leader, for example, that after numerous years, Maurice Blackmore had managed to convince Dr Paul Hoffmeister, an eminent professor from the now defunct Sierra States University in Los Angeles, to teach naturopathic medicine at the Australian College of Naturopathy, Osteopathy and Chiropractic in Sydney (1 of the 3 constituent colleges – based in Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne – of the National Association of Naturopaths, Osteopaths and Chiropractors).19 These relations have continued over many years, with the WPRO naturopathic profession having a long history of collaboration with other regions.

The first official foray of naturopathic education into the university sector was a partnership between Northern Territory University (now Charles Darwin University) and the Queensland Academy of Natural Therapies to develop a 4-year degree course through an institution called the Darwin Academy of Natural Therapies (DANT), which was announced and supported by the Northern Territory health minister of the time.20 In the mid-1990s, reforms in Australia led to the ability of non-government universities and colleges to establish and offer degree courses, with the Australian College of Natural Medicine (Brisbane), Southern School of Natural Therapies (Melbourne), and the Australian Institute of Applied Sciences (Canberra) offering 4-year degree programs by 1995; Southern Cross University offered the first naturopathic program in a public university in 1996. Wellpark College and South Pacific College of Natural Therapies in New Zealand also have longstanding degree programs in naturopathic medicine, which are supported by government-funded placements.

However, as the profession remains largely unregulated or self-regulated in the region (although training exists that is within the highest quartile internationally), several unaccredited colleges still exist that do not meet WHO (or WNF) standards for naturopathic education. As such, the movement towards statutory regulation and recognition remains a priority area within the region. There is also a movement to enact regulations that allow growth in the naturopathic profession. For example, while the New Zealand naturopathic profession training institutions enjoy government funding and degree minimums, they are currently banned from adding an additional fourth year to their program by legislation. However, as in Australia, despite such barriers, the New Zealand profession remains committed to increased standards, including an active research agenda, and coordinates with international profession in research initiatives such as the International Research Consortium of Naturopathic Academic Clinics (IRCNAC) – a North-American and Australasian collaboration leveraging clinical data from college training clinics. Research has more generally been one of the key accomplishments of the naturopathic profession in the WPRO region, with Australian (particularly) and New Zealand practitioners punching well above their weight in terms of research output both internationally with respect to the research output of the broader naturopathic community, and nationally when compared to other complementary therapy disciplines (such as chiropractic, osteopathy, or Chinese medicine) within their own nations.

While several challenges exist, the naturopathic profession in WPRO has numerous opportunities: relatively few practice restrictions, a developing education sector (including recent legislative changes that have banned non-degree education in naturopathic medicine), popular support among the general population, and a naturopathic profession that is holding its own in the international health research community. However, much of this success has occurred despite, rather than because of, government recognition and assistance, and the fragmented nature of the profession has often hampered efforts for greater recognition and integration. Developments such as the WNF have helped to serve as a catalyst for greater cooperation – both within and between countries in the region – and will hopefully provide the professional voice and leadership the profession requires to fully realize its potential in the region.

References:

- Ministry of Health (Malaysia), Traditional and Complementary Medicine Division. National Policy of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2003. Available at: http://tcm.moh.gov.my/en/index.php/policy/national. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Wiwanitkit V, Kaewla W. Public hearing on the first naturopathy curriculum in Thailand. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2015;28(3):213-214.

- Profkes Naturopathic Clinic. Available at: https://profkesclinic.squarespace.com/missions/. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Lust B. Universal Naturopathic Encyclopedia Directory and Buyers’ Guide: Year Book of Drugless Therapy for 1918-19, Volume 1. New York, NY: American Naturopathic Association; 1918.

- Plain Living and High Thinking. February 6, 1906. Darling Downs Gazette. Toowoomba, Queensland.

- Baer HA. The drive for legitimation in Australian naturopathy: success and dilemmas. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(7):1771-1783.

- Martyr P. Paradise of Quacks: An Alternative History of Medicine in Australia. Sydney, Australia: Macleay Press; 2002.

- The Naturopath. Exercise and Rest. January 3, 1903. Darling Downs Gazette. Toowoomba, Queensland.

- In matrimonial jurisdiction. November 3, 1910. The Brisbane Courier. Brisbane, Australia.

- News and Notes. April 6, 1905. Kilmore Free Press. Kilmore VIC, Australia.

- Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Legislative Assembly. October 6, 1955. Available at: https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/documents/hansard/1955/1955_10_06_A.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- Adams J, Sibbritt D, Young AF. Consultations with a naturopath or herbalist: the prevalence of use and profile of users amongst mid-aged women in Australia. Public Health. 2007;121(12):954-957.

- Chow R. Complementary medicine: impact on medical practice. Curr Ther. 2000;41:76-79.

- Cottingham P. History of Naturopathic Medicine in New Zealand. Wellpark College of Natural Therapies. 2005. New Zealand.

- World Naturopathic Federation Report. Findings from the 1stWorld Naturopathic Federation survey. June 2015. WNF Web site. http://worldnaturopathicfederation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/World-Federation-Report_June2015.pdf. Accessed November 5, 2017.

- Evans S. The story of naturopathic education in Australia. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8(4):234-240.

- Taylor J. Submission to the Naturopathic, Osteopathic, Chiropractic Enquiry. 1975. Southern School of Naturopathy; Melbourne, Australia.

- Roberts FG. What Is Drugless Healing? Nature’s Path to Health. February-March 1938; p.36-37.

- Blackmore M. Sydney College Acquires Eminent Lecturers. The Health Leader. 1971;2(1):2.

- Mack R. Academy of Natural Therapies Darwin. Australian Natural Medicine Journal. 1989;2(4):35.