Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH (AHG)

A 15-year-old patient came into my office with 3 concerns. The first was that her immune system was not functioning adequately since she was constantly “catching” viral infections. Symptoms included general malaise, low-grade fever, and body aches, with respiratory symptoms at times. The second concern was mild asthma, primarily induced by exercise or cold; the patient used a steroid inhaler twice a day. The third concern, abdominal migraines, was diagnosed by a gastroenterologist just a few months ago, and was being treated with a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant. The patient reported that the episodes of headache, abdominal pain, nausea and pallor were less frequent and less intense.

It was this last concern, the abdominal migraines, that spurred me into further thinking and research. Was there something substantial about this diagnosis, or was it just a diagnosis of convenience, since the etiology of migraine headaches is unclear and her episodes of headache together with abdominal pain did not have a clear etiology? Was there something about the mechanism of action of the tricyclic antidepressant that could lend further understanding to the cause of this syndrome of symptoms, or to some pathways for naturopathic therapies?

Classification and Diagnostic Criteria

Abdominal migraine is included in the 2004 International Classification of Headache Disorders and recognized by the 2006 Rome III criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. It is most common in children ages 5-9, but can be in older children and adults. The symptoms are abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.

The diagnosis has the following criteria:

- At least 5 attacks fulfilling criteria B-D

- Attacks of abdominal pain lasting 1-72 hours

- Abdominal pain has all of the following characteristics:

- Midline location, periumbilical or poorly localized

- Dull or “just sore” quality

- Moderate to severe intensity

- During abdominal pain, at least 2 of the following:

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Pallor

- Not attributed to another disorder

Pathophysiology

In naturopathic medicine, an unhealthy gut is a primary root of disease, and assisting it in healing becomes a pathway to recovery of health and well-being. Sixty to seventy percent of the immune function is initiated within the gut. Immune modulation is intimately linked with the adrenal glands and the circadian rhythmic output of cortisol. The enteric nervous system (ENS) of the gut , intimately intertwined with the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system, secretes the same neurotransmitters that are secreted in the central nervous system (CNS) in response to inner and outer environmental influences.

Tying these understandings back to my 15-year-old patient, the diminished immune function can be directly related to the dysfunction of her digestive system. The asthma can be a result of food allergy or intolerance causing leaky gut, with the use of the steroid inhaler tied to the diminishment of the adrenal glands and their function. And in this patient, the low-dose tricyclic antidepressant was giving her some relief of the headache and gastrointestinal symptoms. Tricyclic antidepressants increase levels of norepinephrine and serotonin and block the action of acetylcholine. Diminished serotonin levels are associated with an array of chronic diseases, including depression, anxiety, insomnia, addictions, obsessive compulsive disorder, premenstrual syndrome, obesity, and in this case, headaches and abdominal pain.

The Gut Brain

The ENS is often referred to as “the gut brain.” Edgar Cayce called it the “solar plexus brain.” In 1985, Candace Pert pioneered the findings of neuropeptides that are active in the gut and communicating with the brain.1 The ENS extends from the esophagus to the anus, contains greater than 100 million neurons, and secretes every class of neurotransmitters that are also found in the CNS, including norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and others. There are two networks of neurons. First, the ganglia plexus, also known as Myenteric or Auerbach’s Plexus, which is located between layers of tunica muscularis. Auerbach’s Plexus controls GI motility. Second, the submucosal plexus, also known as Meissner’s plexus, which is located in the submucosa, senses the lumen environment, regulating blood flow and controlling epithelial cell function.2, 3 The ENS operates independently of the CNS, however they do communicate through the autonomic nervous system, both parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers. The vagus nerve connects the CNS brain and the gut through these two plexuses. 90% of vagal fibers are centrifugal (not centripetal), bringing information from the gut to the brain.4,5 The ENS also communicates through the enteric endocrine system, the secretion of the gastrointestinal hormones, which are also synthesized in the brain. These include gastrin, cholecystokinin, secretin, ghrelin, motilin, and gastric inhibitory polypeptide.6,7

Treatment

Therapeutics that address the gastrointestinal tract directly will be effective in re-establishing optimal function at the root issue. Therapeutics to modulate the immune system, to balance neurotransmitter activity, to support optimal adrenal function, and eventually to reduce the expression of asthma will all need to be considerations in this case.

In allopathic medicine, the common therapies recommended are NSAIDs, antinausea medication, triptans (ie, sumatriptan succinate), and the combination drug acetaminophen, isometheptene and dichloralphenazone.

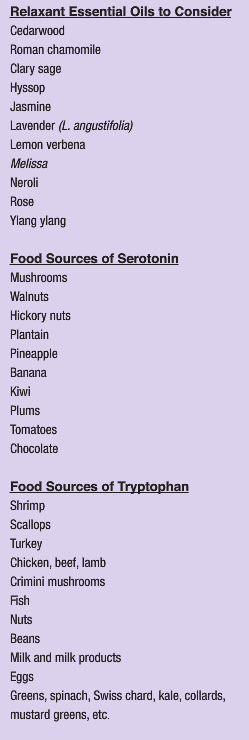

Naturopathic treatment of Abdominal Migraines, therefore, can be centered on treating the gastrointestinal system, with a specific emphasis on the enteric nervous system. Some foundational treatments would include probiotics, castor oil packs mixed with relaxant essential oils (see side bar for list) over the abdomen, and the amino acid glycine to give quieting signals to the locus ceruleus. Nervous system and gut biotherapeutic drainage can take the burden off of these two systems, bringing effective changes.

In addressing neurotransmitter activity, increasing the activity of the more relaxing neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA, will support a parasympathetic state, important in abdominal migraines. Food sources of L-tryptophan (precursor to serotonin) and serotonin are included in the side bar. It is understood that the L-tryptophan foods are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, while serotonin foods are not. If you intake adequate L-tryptophan foods initially to increase blood levels of tryptophan, followed shortly by a carbohydrate snack, it is postulated that you can then increase the serotonin levels in the brain. Potatoes are said to be a main food that moves tryptophan into the brain, which is why they are such a comfort food.8 Exercise, meditation/prayer, laughing, and orgasmic sex will also increase serotonin levels.

Herbal Medicine

The seeds of the Fabaceae family plant Griffonia simplicfolia are reported to be a direct source of 5-HTP, a precursor to serotonin. Many companies in the natural products market claim their 5-HTP products contain Griffonia simplicfolia.

There are numerous herbs that can be considered as part of a treatment plan for treating abdominal migraines based on their overall support of the nervous system, and for some, particularly for their impact on the neurotransmitter activity in both the gut brain and the CNS brain. One of the most researched is Hypericum perforatum, St. John’s Wort, the hyperforin shown to inhibit reuptake of seratonin9 and the whole herb extract acting as a GABA agonist. 10 The valepotriates in Valeriana officinalis, Valerian, yield sedative and antispasmodic activity11 as well as being an agonist for GABA through the valerenic acid. 12 Be aware, however, that Valerian can have the paradoxical effects, seemingly on those people that with significant adrenal fatigue. The exact mechanism of action of Piper methysticum, Kava kava, is unknown, but it is postulated that there is an increase in the number of GABA binding sites13 and dopamine antagonism14, both supporting the increase in parasympathetic activity in the gut. We now that the observed clinical outcomes using Piper methysticum are a decrease in anxiety, a slight sedative effect, and an antispasmodic action. Although thought of as a mild nervine, Melissa officinalis, Lemon balm, is one of the more indicated herbs in working with this condition of abdominal migraines. Melissa influences the neurotransmitters, especially through the inhibition of GABA transaminase, keeping increased levels of GABA available for receptor activity.15. In addition to the neurotransmitter support in the literature for Melissa, we know it traditionally as an herb that can decrease anxiety and lift the spirits. It is a relaxant of both the CNS and the ENS. The opiate herbs, Papaver somnifera, the opium poppy, being the most potent, promote GABA. Other nervine herbs that could be considered because of their ability to support serotonin are Avena sativa, oat straw or milky oat pods, Leonurus cardiaca, Motherwort, Scutellaria lateriflora, Skullcap, Dioscorea villosa, Wild Yam, Actea racemosa, Black cohosh, Ginseng quinquefolius, American ginseng, Rosa canina, rose petals and rose hips, and Cannabis sativa, marijuana.

Adaptogenic herbs would be potentially useful to support the connection between the cortisol output of the adrenal glands and the enteric nervous system. Although most adaptogenic herbs could be considered, the two to be most considered in this case are Withania somnifera, Ashwagandha, and Rhodiola rosea, Roseroot. Withania contains steroidal lactones, some similar to the ginsenosides found in ginseng. It works on the nervous system as an anxiolytic and sedative through suppressing stress-induced increases of dopamine receptors in the brain, lowering the activity of these excitatory neurotransmitters, and through mimicking GABA as well as binding to GABA receptors, increasing the activity of the relaxing neurotransmitters.16 Withania modulates the immune system and support optimal adrenal function through decreasing stress-induced plasma corticosterone.17 Rhodiola rosea, Roseroot, an herb native to the arctic regions of northern Europe, Asia, and Alaska, has shown CNS activity as an anti-depressant and anxiolytic.18,19 Most preparations of Roseola rosea are standardized to 3% rosaven content, and appears to be dose specific, having adaptogenic effects at lower doses and calming effects at higher doses.

Gemmotherapy

The gemmotherapy extract Ficus carica, Fig, is essential in this treatment because of its ability to work at the gut viscera level as well as the ENS connection to the CNS. Fig has the action of disconnecting the firing of neurons between the cortex and hypothalamus in the brain, quieting the excitatory action that can trigger through stress. Crataegus oxycantha, the Hawthorn gemmo will work at the psychosomatic level of emotional disturbances affecting the gut. Viburnum lantana, the Wayfaring Tree gemmo, will act as an antispasmodic. Vaccinium vitis idaea, Cowberry gemmo, has a trophism for gut mucosa, bringing homeostasis to all areas, but especially the small and large intestine. Tilia tomentosa, Linden Tree gemmo, is CNS calming, affecting the ENS through direct communication. Juglans regia, Walnut gemmo, works well in cases of dysbiosis to support and environment where there can be a proliferation of healthy flora in the gut.

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic med-icine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical prac-tice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND con-sultant

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic med-icine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical prac-tice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND con-sultant

References

- Pert C. Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1999.

- Hansen MB. The enteric nervous system I: organisation and classification. Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2003; 92(3):105-113.

- Goyal RK, Hirano I. The enteric nervous system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17);1106-1115.

- Hoffman HH, Schnitzlein HN. The numbers of nerve fibers in the vagus nerve of man. Anat Rec. 1961;139:429-435.

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Gastrointestinal afferent fibers and sensation. In: Johnson LR, Aplers DH, Jacobson ED., et al, eds. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, 3rd ed., vol 1. New York: Raven Press; 1994:482-520.

- Bowen R. The enteric endocrine system. www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/digestion/basics/gi_endocrine.html. Accessed November 25, 2009.

- Bowen R. The enteric nervous system. www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/digestion/basics/gi_nervous.html. Updated June 24, 2006. Accessed November 25, 2009.

- DesMaisons K. Potatoes Not Prozac. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1998.

- Tadros MG, et al. Involvement of serotoninergic 5-HT1A/2A, alpha-adrenergic and dopaminergic D1 receptors in St. John’s wort-induced prepulse inhibition deficit: a possible role of hyperforin. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199(2):334-339.

- Müller WE. Current St John’s wort research from mode of action to clinical efficacy. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47(2):101-109.

- Houghton PJ. The scientific basis for the reputed activity of Valerian. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1999;51(5):505-512.

- Yuan CS, et al. The gamma-aminobutyric acidergic effects of valerian and valerenic acid on rat brainstem neuronal activity. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(2):353-358.

- Boonen G, et al. Evidence for specific interactions between kavain and human cortical neurons monitored by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Planta Med. 2000;66(1):7-10.

- Seitz U, et al. [3-H]-monoamine uptake inhibition properties of kava pyrones. Planta Med. 1997;63(6):548-549.

- Awad R, et al. Bioassay-guided fractionation of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) using an in vitro measure of GABA transaminase activity. Phytother Res. 2009;23(8):1075-1081.

- Upton R, ed. Ashwagandha Root (Withania somnifera); Analytical, quality control, and therapeutic monograph. Santa Cruz, CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia; 2000:1-25.

- Mishra LC, et al. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha): a review. Altern Med Rev 2000;5(4):334-346.

- Perfumi M, Mattioli L. Adaptogenic and central nervous system effects of single dose of 3% rosavin and 1% salidroside Rhodiola rosea L. extract in mice. Phytother Res. 2007;21(1):37-43.

- Bystritsky A, et al. A pilot study of Rhodiola rosea (Rhodax) for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(2):175-180.