Lisa Meserole, MS, ND

“Old age itself is not a disease, but a condition which may lead to illness on various levels due to the hyporeactivity characteristic of this state … Aging constitutes an inability to correctly respond to various rivaling stimuli.” – Bianchi, 1994

Treating patients ages 65 and older requires specialized clinical skills and familiarity with the physiology and common conditions of this phase of life. For most individuals, there are health shifts away from middle age at 65, but the biggest changes are often after age 75 or 80. Just as children display narrow bands of tolerance for infection, dehydration, starvation and other stress, so do seniors, although they typically manifest crisis states at a delayed rate compared to children.

Avoiding Malnutrition in the Elderly

Anti-aging nutrition and phytotherapy can be of tremendous benefit to seniors when elegantly applied and individualized. Seniors pose a challenge because their response and tolerance to treatment varies more widely than when they were middle aged. Anti-aging nutrition means nutrient-dense, high-quality whole food, organic when practical and free of antibiotics, fungicides, molds, bacteria, hormones and hazardous residues. The Mediterranean diet – high in fresh fruits, vegetables, grains, olive oil, nuts and seeds, lean protein; low in refined food, saturated fat, sugar and meat – has been associated with reduced risk of heart disease, diabetes, obesity and Alzheimer’s. Flavonoid and antioxidant science is discovering the vast benefits of these actives in greens, fruits, produce, whole grains, vegetable seed oil, and culinary and medicinal herbs. And although supplements are useful, they do not substitute for the array of naturally occurring, heterogeneous constituents in quality diets.

Seniors are at high risk for reduced nutritional intake, nutritional absorption and nutritional status due to various age-related factors: dentures and mouth pain; swallowing incoordination; dry mouth/esophagus (aggravated by many drugs); nausea (drug, disease, gastric motility induced); constipation or diarrhea (less food causes fewer symptoms); abdominal pain (gall stones, ulcers, cancer, angina, ascites); impaired smell, taste, sight and taste make food less enjoyable; eating and food preparation are impaired by arthritis, dementia, depression; etc. New studies suggest that reduced gut cholecystokinin and neuropeptides diminish the drive to eat and increase satiety threshold (Morley, 1997) The Merck Manual of Geriatrics is a useful clinical resource for physicians who see patients ages 65 and older.

Seniors are at high risk for reduced nutritional intake, nutritional absorption and nutritional status due to various age-related factors: dentures and mouth pain; swallowing incoordination; dry mouth/esophagus (aggravated by many drugs); nausea (drug, disease, gastric motility induced); constipation or diarrhea (less food causes fewer symptoms); abdominal pain (gall stones, ulcers, cancer, angina, ascites); impaired smell, taste, sight and taste make food less enjoyable; eating and food preparation are impaired by arthritis, dementia, depression; etc. New studies suggest that reduced gut cholecystokinin and neuropeptides diminish the drive to eat and increase satiety threshold (Morley, 1997) The Merck Manual of Geriatrics is a useful clinical resource for physicians who see patients ages 65 and older.

Since a patient’s life can be saved by an alert physician who promptly diagnoses malnutrition or sudden dehydration (often missed because symptoms are attributed to existing disease), see Table 1 for a review of symptoms (adapted from Hamilton, 2001). Table 2 provides a list of common nutrient deficiencies in the elderly.

Anti-Aging Nutrition and Phytomedicine Indications

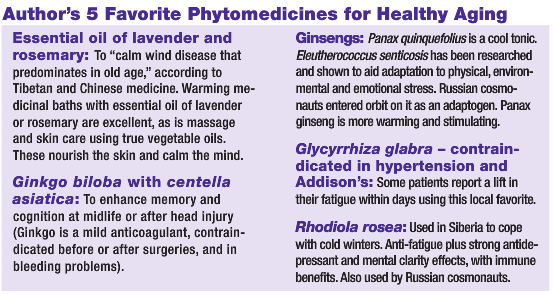

Hundreds of anti-aging products are available today, and their number is rapidly growing. Every practitioner has a list of essentials for the healthy patient who wants an anti-aging regimen.

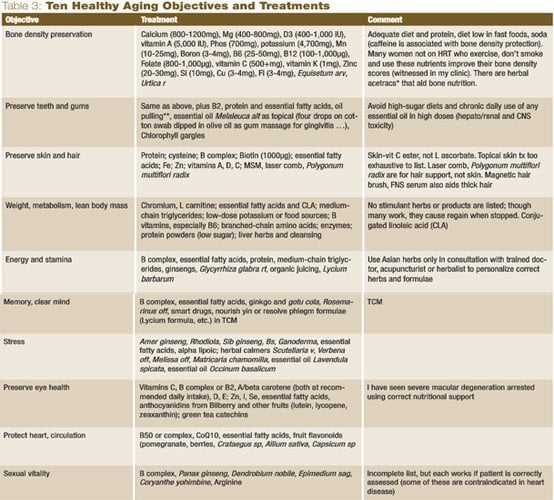

Acknowledging the impracticality of attempting to discuss every anti-aging agent, what is suggested in Table 3 is a partial list of those with a good clinical track record according to my clinical observations.

Anti-aging nutrition and phytotherapy can prolong health, contribute to longevity and enhance the quality of life. The physician’s first priority is to prevent or recognize elderly malnutrition or dehydration and diagnose disease. The second is to tailor a program to each patient, with an armamentarium of traditional and science-based lifestyle, dietary, nutrient and phytomedicine recommendations that target the problems of vitality, inflammation, memory and vision loss, skin health, depression, chronic pain, GI and heart disease, and more. Emerging research makes ours an exciting time to blend traditional knowledge with new discoveries.

Anti-aging nutrition and phytotherapy can prolong health, contribute to longevity and enhance the quality of life. The physician’s first priority is to prevent or recognize elderly malnutrition or dehydration and diagnose disease. The second is to tailor a program to each patient, with an armamentarium of traditional and science-based lifestyle, dietary, nutrient and phytomedicine recommendations that target the problems of vitality, inflammation, memory and vision loss, skin health, depression, chronic pain, GI and heart disease, and more. Emerging research makes ours an exciting time to blend traditional knowledge with new discoveries.

Lisa Meserole, MS, ND has been in clinical practice since 1990. Between 1990-2001, she worked in integrated medical clinics. Her introduction to laboratory research began in 1975, when she worked in human, animal and tissue culture nutrition research projects. Dr. Meserole was chair of the Bastyr University nutrition program for three years, and later chair of botanical medicine for three years. She studied Western and eclectic botanical medicine at Bastyr, while including Chinese and Tibetan herbal medicine in her education. Dr. Meserole earned a master’s in human nutrition from the University of Washington and was a registered dietitian for 12 years. She was project coordinator for a clinical trial pilot study on a plant-based medication for HIV patients at Bastyr Research Institute; and was a founding board member of the Bioresources Development and Conservation Programme. Her chapter on Western Herbalism appears in Fundamentals of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (Churchill Livingston, 1995). Dr. Meserole’s primary interests include: integrated holistic primary healthcare, endobiogeny, clinical botanical medicine, nutrition and research, and issues of quality control and sustainable worldwide access to medicinal plants and foods.

Lisa Meserole, MS, ND has been in clinical practice since 1990. Between 1990-2001, she worked in integrated medical clinics. Her introduction to laboratory research began in 1975, when she worked in human, animal and tissue culture nutrition research projects. Dr. Meserole was chair of the Bastyr University nutrition program for three years, and later chair of botanical medicine for three years. She studied Western and eclectic botanical medicine at Bastyr, while including Chinese and Tibetan herbal medicine in her education. Dr. Meserole earned a master’s in human nutrition from the University of Washington and was a registered dietitian for 12 years. She was project coordinator for a clinical trial pilot study on a plant-based medication for HIV patients at Bastyr Research Institute; and was a founding board member of the Bioresources Development and Conservation Programme. Her chapter on Western Herbalism appears in Fundamentals of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (Churchill Livingston, 1995). Dr. Meserole’s primary interests include: integrated holistic primary healthcare, endobiogeny, clinical botanical medicine, nutrition and research, and issues of quality control and sustainable worldwide access to medicinal plants and foods.

References

Bianchi I: Geriatrics and Homotoxicology (ed 2), Baden Baden, 1994, Aurelia-Verlag, p 29.

Morley JE: Anorexia of aging: physiologic and pathologic, Am J Clin Nutr, 66:760-773, 1997.

Brown S: The Osteoporosis Education Project, 2005.

Wilkinson TJ et al: The response to treatment of subclinical thiamine deficiency in the elderly, Am J Clin Nutr 66:925-28, 1997.

Hamilton S: Detecting dehydration in the elderly, Nursing Dec, 2001.