Sheryl Wagner ND

Mind-body medicine equals holism. When physicians get to know the whole patient to treat the mind-body, we get to know the physical, mental, and emotional experience of a patient. Researching the cause of symptoms means uncovering the stressors in the patient’s life. It is not uncommon for patients to break down in tears during a visit. Spending time with our patients (an hour or more for initial consultations and 30-45 minutes for return visits) inevitably leads to their revealing much about their emotional lives.

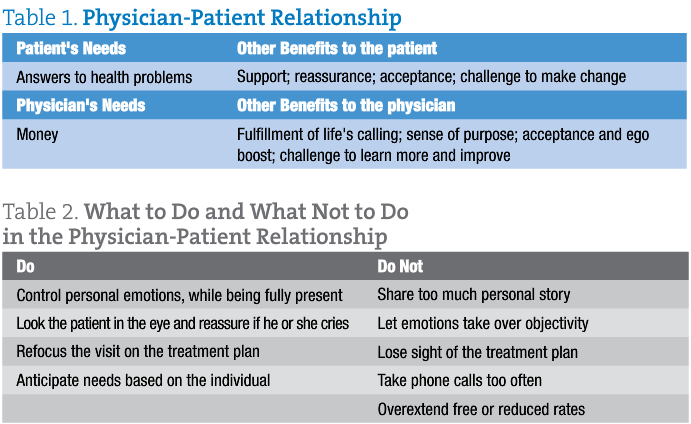

While this sharing of intense personal information can make the patient feel close to the physician, the physician can also be pulled in to feel connection with the patient. Compassion is a strong driving force in calling someone to a career as a physician. Most of us naturally want to help, and many of us have experienced our own physical setbacks and healing journeys. The draw to share in a patient’s journey, offer comfort, and somehow fix him or her can present a problem for the physician.

How involved do we get emotionally when we hear our patients’ stories? How much responsibility for the healing outcome can we take? What happens when a patient dies? Will a patient turn on us even when we have done all we can for him or her? These can be ways we experience heartbreak as physicians. The important goal to keep in mind is to give every patient what he or she truly needs from us, the physician, at each visit.

Do Not Let Emotions Get the Best of You

A grandmother and granddaughter who scheduled a visit in my second year of practice declined to state ahead of time what the major health concern was. Coming into the office, they had an air of secrecy as they gazed about, made sure the door was closed, and looked at each other before speaking. Then they revealed why they had come: believing the girl’s stepfather was poisoning her, they were requesting a heavy metal test for arsenic. They detailed the events that had occurred and the girl’s symptoms, as well as what the police had said and what they needed from me. I said something about different tests and excused myself from the room, presumably to get a test kit.

As I looked at testing methods, I could not think. I felt myself tearing up. I realized that I was not just thinking about the girl’s situation but about my own daughter’s life. It was no secret that my daughter and my husband (her stepfather) did not get along. Was I in denial, like this other girl’s mom? How bad was our situation really?

I had to stop thinking about this and focus on the patient at hand. I realized right away that no matter how much I wanted to help them, no matter how desperate they were, I could not treat the girl until I had parental consent. The grandmother did not have custody. They would have to get at least one parent’s signature. Had I not thought clearly, my practice license could have been at risk. They were able to eventually meet the requirements, and we tested and treated accordingly.

Focus on the Patient’s Story, Not Yours

More commonly, it is the patient who tears up or cries during the visit. This can make the physician feel uncomfortable or want to commiserate. It is important to remember that your role as a physician is to get the patient closer to the treatment plan. That could mean giving encouragement, hope, strength, and (most important) information. Making simple statements like “That can be tough” or “It’s not all in your head” or “We’ll figure this out” may be the transition needed to refocus on a treatment plan. What the patient does not need is for the physician to also break down in tears and share his or her own health journey, commiserating with the patient to the point of losing sight of the physician’s purpose in the encounter. I recently received a new patient who had already seen a DO and an ND. The DO had not been sensitive enough, and the ND had broken down in tears and shared her own story. The patient did not feel listened to with the first physician and had felt uncomfortable (rather than understood) when the second physician cried. She needed strength and reassurance, not commiseration.

When I read the forwarded medical record notes from the 2 physicians for this particular patient, it was apparent that she had lost faith in the treatment plan when she did not feel good right away. She also had a habit of calling the office rather than coming back for a return visit. No doubt, this had led to failure to comply and then eventually giving up. I would have to watch for that. Her father had also alerted me to a couple of other fears of physicians that she had. During her visit with me, she was almost in tears, and I remained calm and focused. I made sure she knew I believed in our treatment plan. I was careful not to step on her toes in terms of her fears but made sure she knew what my expectations were for the next steps. She waffled a bit, first saying she would like to be treated based on old test results but then later changed her mind and wanted new tests performed before moving forward with treatment. I would have to make sure she came back as scheduled, whether or not I received the test results she was supposed to mail. She would likely need an extra push to follow through, and I could not let it bother me or take it personally that she did not have faith in physicians in general. Although I myself had received test results similar to hers, I made it a point not to go into too much detail about my own story.

Sympathizing a bit can be all right as long as it does not hijack the appointment. Many women struggle with irritability during menopause, and one woman in particular seemed rather sane and jovial, despite the irritability she described with her children. When the treatment plan solved this but had not helped the relationship with her husband, we got to talking about men. When we realized that our husbands had some things in common, she exclaimed: “Why are they so black and white?” I had shared my experience in a “What can you do?” sort of way and had suggested a book on loving a spouse with Asperger syndrome. When she came back months later for a different concern, she said the book had helped. However, it was a little awkward when she found out my marriage had just ended in divorce. Still, I managed to keep the focus on how to help her with the chief complaint at hand.

Overextending Yourself Can Lead to Bad Feelings Toward the Patient

Then there are the needy patients. We have all had them. They are drawn to alternative medicine like no one else. Usually, these are the people who on their first call to the office need to come in today, right now, although their complaints have been going on over a year or more. Not only that, they do not have enough money to pay full price. They almost always have anxiety, which draws you in to their situation. These are the patients for whom you may feel compelled to do something new, something other physicians and those at the emergency department did not think of. No matter what treatment plan you offer, the patient will call back the next day with a million questions and want to ask about this or that he or she read on the Internet. These patients can certainly consume your time, but you want to give them the attention they need if the outcome will be worthwhile.

Usually, the relationship will go something like this: they feel assured when in the office, but they doubt you once they leave. They do not follow the treatment plan right away but instead go to the health food store and purchase a bunch of supplements you did not prescribe. They e-mail constantly, especially when they feel bad. I have found that if you make them wait until their scheduled appointment to report back to you, the report will usually be much more positive or at least balanced. When they finally try your treatment plan, they do feel better. In fact, they think you saved their life; they are going to tell everyone about you! Then a couple of weeks later, they feel terrible, and you do not know enough to help them. It is pretty apparent that anxiety or an unstable personality is at the core of their problem, and the physician cannot hang his or her worth on praise or condemnation by these patients. Such patients will take time to figure out, and if you overextend your availability to them, you will quickly develop negative feelings toward them.

Personal Involvement Does Happen

In school, we were told not to treat your own family, but what about friends? Although it is not common for a patient to become a friend, friends and acquaintances often become patients. I do not mind the few extra e-mails they send or the trip to the office on a Saturday to run a rapid streptococcal test. However, the close relationship causes the business relationship to become more personal. It would be easy in these cases for the personal relationship to suffer because of frequent health questions outside of the office or for the business relationship to suffer if the physician takes too much responsibility for the health outcome of the patient.

I met a lady at a retreat who was 6 years into treatment for breast cancer. My immediate reaction to finding out how long her treatment had continued was heavy hearted. She was thin, bald, and ashen and had to take breaks from activity because of the nausea and fatigue she was experiencing. This, I thought, did not bode well for her recovery. She was following her physician’s orders with chemotherapy but wanted to include natural treatments such as saunas. I gave her the name of a physician who specializes in cancer care, but she did not have a lot of money for another physician or for supplements.

We had talked about our kids, and she offered her horses for my daughter and me to ride. I offered Nambudripad allergy elimination techniques and homeopathy. I went to her house on a few occasions with my daughter, and we had long chats. She taught me how to ride an English saddle, and I gave her allergy elimination treatments and Arsenicum album. She felt improvement in energy and stomach pain, and I got some well-needed friendship during my divorce. At our last visit, the notion hit me that I felt sorry for her daughters, aged 6 and 8 years. All they had known was an ill mother. She and her daughters came to my daughter’s birthday party a couple of weeks later, and when they left, she told me several times: “It was a lovely party, just wonderful.” I felt like she was saying goodbye. She looked so tired.

I did not hear from her for almost 2 months because we were both supposed to take vacations. I called her phone on a Thursday, our day to get together. Her husband answered and said she was in the hospital and was so doped up on pain medication that she did not recognize anyone. A week later, I called again, and he informed me that she had just died 4 hours before my call. He told me she had really appreciated my friendship.

My first reaction was: “Why didn’t I do more? Why didn’t I follow up more often? Why haven’t I been interested in cancer care, when chances are I’m going to know someone with cancer?” At her funeral, I discovered that her goal had been to stay alive long enough to see her daughters get baptized, which had been accomplished 10 months before her death. Rather than take too much responsibility for a death from cancer, I refocused on being there for her family, making it a point to learn more about cancer and to have a more urgent concern for my patients and friends, should they be diagnosed as having cancer.

Given the intimate nature of mind-body medicine, the physician-patient relationship can be tricky and get personal but can definitely be positive in both the lives of patient and physician. It is important for us to remember to always offer strength and a listening ear and to refocus attention on the treatment plan, whenever needed. Although we may be affected by our patients’ conditions and struggles or by what they say about us, our scientific training allows us to remain objective, without being stoic or distant. In this way, we can offer our patients an environment in which they can achieve true healing.

Sheryl Wagner, ND is a graduate of National College of Natural Medicine (Portland, Oregon) and University of California (Davis) and is a primary care physician in the state of Washington. She treats patients of all ages and concerns, with a large portion of her practice focused on allergy treatments, autism spectrum and behavioral issues, and gastrointestinal disorders.

Sheryl Wagner, ND is a graduate of National College of Natural Medicine (Portland, Oregon) and University of California (Davis) and is a primary care physician in the state of Washington. She treats patients of all ages and concerns, with a large portion of her practice focused on allergy treatments, autism spectrum and behavioral issues, and gastrointestinal disorders.