Women’s Sleep Through the Ages

Catherine Darley, ND

Women’s sleep is uniquely influenced by hormonal changes throughout their life span. Generally, it is found that women have more sleep-related complaints than men, although women have better sleep quality. Women overall take less time to fall asleep, have longer sleep duration, and spend a higher percentage of the time in bed sleeping.1

As women age, the prevalence of sleep disorders among them shifts. These sex differences begin with the onset of puberty. Let us take a look at how women sleep at each age.

Reproductive Years

It is common in the office to hear patients say “During the week before my period begins, I need more sleep, and my sleep is more disrupted.” This experience is also noted in research. Women with premenstrual mood symptoms have more stage 2 sleep, with less deep sleep and altered circadian rhythms of temperature and melatonin. This is accompanied by subjective complaints of increased daytime sleepiness.2

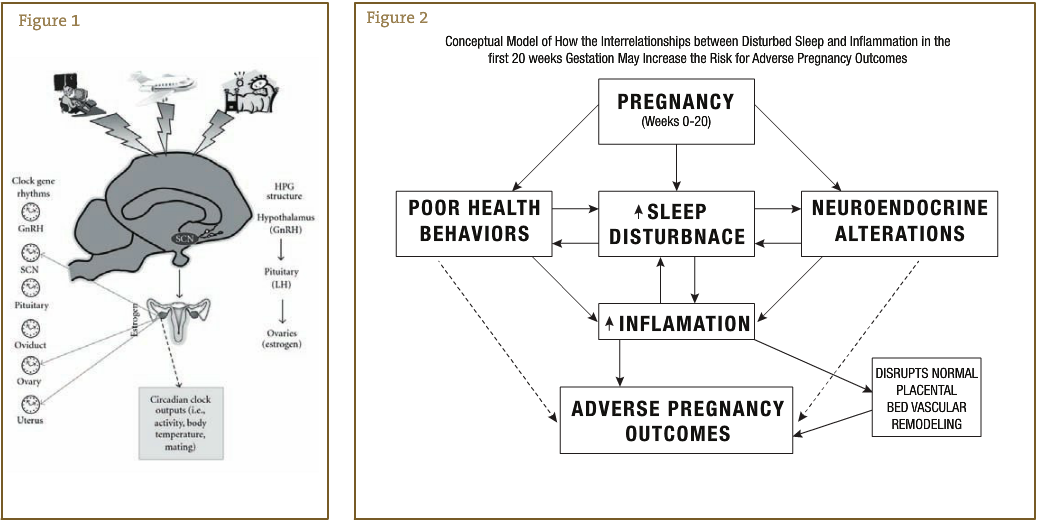

Reproductive health is worsened by shift working (swing, night, or an irregular schedule). Women on such schedules experienced variable cycle length, altered amount of bleeding, and increased pain. Ovarian and pituitary hormone patterns are changed, lengthening the follicular stage.3

Women with primary dysmenorrhea have pain that decreases their sleep quality subjectively and alters the amount of rapid eye movement sleep. These women not only have sleep changes during menstruation but also have higher nocturnal body temperatures and different hormone levels and sleep patterns throughout the menstrual cycle compared with control subjects having normal menstruation.4

Pregnancy

During healthy pregnancy, sleep changes during each trimester. The first trimester is known for greater daytime sleepiness and increased sleep times. During the second trimester, women tend to sleep the best and have a resurgence of their daytime energy. The third trimester sees a return of sleep difficulties, including an inability to find a comfortable sleeping position. Nasal tissues swell during the last trimester, causing more snoring. The incidence of restless legs syndrome also increases during the last trimester.

In 2009, Okun and colleagues5 proposed a model in which disturbed sleep may contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes, which are on the rise. They suggest that the inflammation caused by sleep disruption during early pregnancy “can act to inhibit the trophoblast invasion and associated remodeling of maternal blood vessels that perfuse the placenta.”5(p) Their hypothesis is relevant for preeclampsia, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth retardation.5 In a notable study,6 continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy was administered to pregnant women with hypertension. (CPAP is a common treatment for obstructive sleep apnea whereby the upper airway is splinted open with positive air pressure, thus preventing obstructions.) The CPAP group’s blood pressure decreased, while the control group’s blood pressure increased, and the treatment infants had higher 1-minute Apgar scores than controls.

Short sleep duration is associated with heightened obesity and metabolic syndrome in men and in nonpregnant women. A small study7 looked at the relative risk of gestational diabetes among pregnant women based on their nightly sleep duration. The relative risk of developing gestational diabetes was 5.56 for women who slept 4 hours or fewer per night compared with women who slept 9 hours nightly. This risk increased to 9.83 for overweight women and also increased for those who snored.

Immediately postpartum, women tend to have higher amounts of slow-wave sleep. Women who rate their sleep as worse at this time are at greater risk for postpartum mood problems.8

Menopause

During the menopausal transition, about 40% of women say that their sleep complaints are among the worst of menopausal symptoms.9 Women may have hot flashes and night sweats that disturb their sleep. Even women who do not have these symptoms may experience sleep disturbance, as there is no longer an effect of estrogen on energy metabolism. Primary menopausal insomnia is considered a normal part of the menopausal experience.10 The use of conventional hormone therapy improves sleep quality by decreasing wake time after sleep onset.11 This is a growing area of research in sleep medicine, as are many women’s sleep health topics.

The incidence of sleep apnea in women increases at this age. Sleep apnea in itself can result in symptoms of nonrestorative sleep and daytime sleepiness.12

Conclusion

Sleep complaints are common among women of all ages. As a woman ages, her risk of certain sleep disorders shifts based on her menstrual status. Sleep problems may also affect reproductive health and maternal and fetal outcomes.

As NDs, we have many tools to improve hormone balance and overall health. Using naturopathic principles and providing patient education, we may be able to decrease the incidence of sleep disorders among women as they move through life.

Catherine Darley, ND practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. Dr Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. While attending Bastyr, Dr Darley did shift work many nights at Seattle area sleep labs, so this topic is close to her heart. In addition to providing patient care, she does public sleep education and corporate consultations.

Catherine Darley, ND practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. Dr Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. While attending Bastyr, Dr Darley did shift work many nights at Seattle area sleep labs, so this topic is close to her heart. In addition to providing patient care, she does public sleep education and corporate consultations.

References

- Krishnan V, Collop NA. Gender differences in sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(6):383-389.

- Driver HS, Baker FC. Menstrual factors in sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 1998;2(4):213-229.

- Chung FF, Yao CC, Wan GH. The associations between menstrual function and life style/working conditions among nurses in Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2005;47(2):149-156.

- Baker FC, Driver HS, Rogers GG, Paiker J, Mitchell D. High nocturnal body temperatures and disturbed sleep in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(6, pt 1):E1013-E1021.

- Okun ML, Roberts JM, Marsland AL, Hall M. How disturbed sleep may be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64(4):273-280.

- Poyares D, Guilleminault C, Hachul H, et al. Pre-eclampsia and nasal CPAP, part 2: hypertension during pregnancy, chronic snoring, and early nasal CPAP intervention. Sleep Med. 2007;9(1):15-21.

- Qui C, Enquobahrie D, Frederick IO, Abetew D, Williams MA. Glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes risk in relation to sleep duration and snoring during pregnancy: a pilot study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:e17.

- Bei B, Milgrom J, Ericksen J, Trinder J. Subjective perception of sleep, but not its objective quality, is associated with immediate postpartum mood disturbances in healthy women. Sleep. 2010;33(4):531-538.

- Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Sleep. 2010;33(4):539-549.

- Bourey RE. Primary menopausal insomnia: definition, review, and practical approach. Endocr Pract. 2010:1-28.

- Tranah GJ, Parimi N, Blackwell T, et al. Postmenopausal hormones and sleep quality in the elderly: a population based study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:e15.

- Polo-Kantola P, Saaresranta T, Polo O. Aetiology and treatment of sleep disturbances during perimenopause and postmenopause. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(6):445-452.