Eric Yarnell, ND

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protease produced by prostate cells to liquefy the semen. Though it is found in non-prostatic cells in minute amounts, it is largely a product of the prostate and thus fairly specific for problems in that organ. Unfortunately, the idea that PSA levels are a direct marker of lethal prostate cancer has never been borne out, and in fact is rather biologically implausible. This article will review PSA blood testing and why it is a failed test.

Minimal Initial Impact on Death Rates

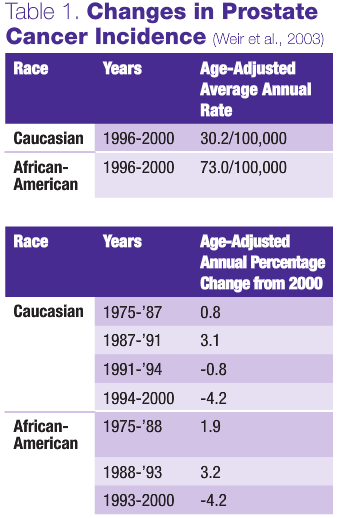

PSA actually refers to total serum PSA levels (tPSA). Testing was approved for use in 1986 by the U.S. FDA, at first only to monitor therapy and then later for screening. The promise of greatly lowered death rates without excessive treatment did not pan out. Prior to the introduction of PSA, the death rate from prostate cancer was slowly increasing, and it continued to do so until 1992, when the death rate began to fall.

It has been demonstrated that the small decline in mortality seen relatively soon after the test was introduced is unlikely to be the direct result of the test, primarily because it happened too quickly (Etzioni et al., 1999; Quinn and Babb, 2002). Lead-time bias more appropriately describes the apparent change in mortality figures (Dennis and Resnick, 2000).

No Evidence of Benefit in Clinical Trials

Two large double-blind trials involving a total of more than 55,000 participants have been conducted investigating whether mass tPSA screening is beneficial. A meta-analysis of these two trials concluded “… there is insufficient evidence to either support or refute the routine use of mass, selective or opportunistic screening compared to no screening for reducing prostate cancer mortality.” No strong evidence is available regarding the impact of screening on quality of life, harms from screening or an assessment of economic value (Ilic et al., 2006). Two more very large clinical trials addressing this question are presently underway, but the data will not be available for years. Without this definite proof of efficacy, it is shocking that so many life-changing decisions are based almost solely on tPSA testing (whether to biopsy and then whether to do invasive treatment).

Biological Implausibility

The idea that tPSA should rise with prostate cancer and no other condition is highly flawed. It is well-known that the worse and more advanced the neoplastic process is, the more cells tend to lose their normal function. In other words, the worst prostate cancers will make less or no tPSA. This is evident from the fact that many men (15%-25% of cases in clinical trials) with normal tPSA readings still have and die of aggressive prostate cancer (Thompson et al., 2004).

The idea that tPSA should rise with prostate cancer and no other condition is highly flawed. It is well-known that the worse and more advanced the neoplastic process is, the more cells tend to lose their normal function. In other words, the worst prostate cancers will make less or no tPSA. This is evident from the fact that many men (15%-25% of cases in clinical trials) with normal tPSA readings still have and die of aggressive prostate cancer (Thompson et al., 2004).

Why tPSA rises at all related to prostate cancer is somewhat of a mystery. It has been hypothesized that this is due to PSA leak, resulting from disruption of the blood-prostate barrier when neoplastic cells reduce their attachment to the basement membrane, disrupting its intregrity (Stenman et al., 1999).

It is increasingly clear that benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) contributes significantly to serum tPSA, and that tPSA rises over time due to BPH. The situation is so serious that one of the leading urologists in the U.S. has concluded that a tPSA reading below 10ng/ml (and possibly below 20ng/ml) no longer bears any relationship to prostate cancer diagnosis or mortality (Stamey et al., 2004). Another analysis has shown that 66% of men with elevated tPSA do not have prostate cancer (Selley et al., 1997).

Massive Overuse of Biopsy and Overtreatment: A Failed Strategy

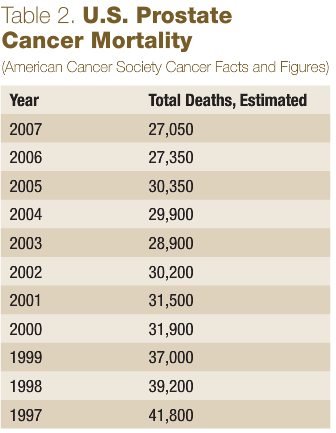

Table 2 shows the absolute decline in estimated prostate cancer deaths in recent times. Initially this looks extremely promising, with significant declines in prostate cancer mortality. However, these changes reflect only the upside of a grim reality – massive overtreatment. From 1984 to 1990, the population-adjusted rate of radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer rose 5.75 times in the U.S. (Lu-Yao et al., 1993). Of course, prostate cancer death rates did not fall near 6-fold. Out of 10,598 prostatectomies identified from 1984-’90, 2% resulted in patient death and 8% in severe cardiopulmonary morbidity (affecting approximately 1,000 men). Radiation therapy, orchidectomy and hormone suppressive drugs are not exactly mild treatments, either.

Table 2 shows the absolute decline in estimated prostate cancer deaths in recent times. Initially this looks extremely promising, with significant declines in prostate cancer mortality. However, these changes reflect only the upside of a grim reality – massive overtreatment. From 1984 to 1990, the population-adjusted rate of radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer rose 5.75 times in the U.S. (Lu-Yao et al., 1993). Of course, prostate cancer death rates did not fall near 6-fold. Out of 10,598 prostatectomies identified from 1984-’90, 2% resulted in patient death and 8% in severe cardiopulmonary morbidity (affecting approximately 1,000 men). Radiation therapy, orchidectomy and hormone suppressive drugs are not exactly mild treatments, either.

The conventional urology standard of care when tPSA is elevated is to perform a biopsy. According to urologist Richard Getzenberg, MD, 1.6 million prostate biopsies are performed each year in the U.S., and 80% show the presence of no cancer. This is not a trivial procedure, and it has significant economic costs, though luckily the morbidity is generally mild.

Thus, tPSA screening has led to a massive wave of unnecessary biopsies and aggressive treatment (Chamberlain et al., 1997), resulting in approximately 30%-40% declines in the death rate. Many, many men who would never die of prostate cancer are being treated, and some are dying or being severely injured by this treatment. By sheer luck, some men with more serious prostate cancers are being caught and treated – sheer luck since the clinical trials discussed above have not shown that tPSA screening reduces mortality. The economic and human costs of this enormous overuse of biopsy and overtreatment are still largely ignored.

tPSA screening cannot currently be justified. This is unfortunate, as there is no better alternative. Digital rectal examination is still justifiable, though it will also miss many cancers and lead to unnecessary biopsies in some cases. The sad fact remains that there is no way to reliably detect aggressive prostate cancer before it becomes a problem.

Eric Yarnell, ND is a graduate of Bastyr University. He completed a two-year residency with Silena Heron, ND, and served as chair of botanical medicine at SCNM. He is past senior editor of the Journal of Naturopathic Medicine. Dr. Yarnell is a founding member and current president of the Botanical Medicine Academy and author of numerous textbooks and articles, including Naturopathic Urology and Men’s Health, Naturopathic Gastroenterology and Clinical Botanical Medicine. His area of clinical focus is urology and men’s health. He is assistant professor in botanical medicine at Bastyr University.

Eric Yarnell, ND is a graduate of Bastyr University. He completed a two-year residency with Silena Heron, ND, and served as chair of botanical medicine at SCNM. He is past senior editor of the Journal of Naturopathic Medicine. Dr. Yarnell is a founding member and current president of the Botanical Medicine Academy and author of numerous textbooks and articles, including Naturopathic Urology and Men’s Health, Naturopathic Gastroenterology and Clinical Botanical Medicine. His area of clinical focus is urology and men’s health. He is assistant professor in botanical medicine at Bastyr University.

References

Chamberlain J et al: The diagnosis, management, treatment and costs of prostate cancer in England and Wales, Health Technol Assess 1(3):i-vi,1-53, 1997.

Dennis LK and Resnick MI: Analysis of recent trends in prostate cancer incidence and mortality, Prostate 42(4):247-52, 2000.

Etzioni R et al: Cancer surveillance series: Interpreting trends in prostate cancer – Part III: Quantifying the link between population prostate-specific antigen testing and recent declines in prostate cancer mortality, J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1033-9, 1999.

Ilic D et al: Screening for prostate cancer, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD004720, 2006.

Lu-Yao GL et al: An assessment of radical prostatectomy. Time trends, geographic variation, and outcomes. The Prostate Patient Outcomes Research Team, JAMA 269:2633-6, 1993.

Quinn M and Babb P: Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part II: individual countries, BJU Int 90:174-84, 2002.

Selley S et al: Diagnosis, management and screening of early localised prostate cancer, Health Technol Assess 1(2):i,1-96, 1997.

Stamey TA et al: The prostate specific antigen era in the United States is over for prostate cancer: What happened in the last 20 years?, J Urol 172:1297-301, 2004.

Stenman UH et al: Prostate-specific antigen, Semin Cancer Biol 9:83-93, 1999.

Thompson IM et al: Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level less than or equal to 4.0 ng per milliliter, N Engl J Med 350:2239-46, 2004.

Weir HK et al: Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control, J Natl Cancer Inst 95:1276-99, 2003.