Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO

There is a huge Korean grocery near my office. I drove over the other day to study the mushrooms that they sell.

My newfound interest in mushrooms is sparked by the publication of a study on mushroom consumption and breast cancer risk in the International Journal of Cancer in February (Hong et al., 2008).

Researchers from Seoul, South Korea recruited 362 women with breast cancer between 30 and 65 years of age and matched them to controls by age and menopausal status. All the women were questioned carefully to determine how many mushrooms they ate and how often. The researchers took this information and calculated that eating mushrooms lowers risk of breast cancer.

In the study, the associations between the daily intake and the average consumption frequency of mushrooms with breast cancer risk were evaluated using matched data analysis. The women who ate mushrooms the most frequently had a 52% reduction in overall risk when compared to the women who ate mushrooms the least often. Those who ate the most mushrooms had a 46% reduction in risk. When this basic data was analyzed by menopausal status, a much stronger effect was seen. In postmenopausal women, there was an 84% reduction in risk for the frequent mushroom eaters. Likewise, there was an 83% reduction in risk for those who ate the most mushrooms. No benefit was apparent in premenopausal women.

Numbers like these should get our attention. What is going on here?

Estrogen and Aromatase Inhibition

Estrogen and Aromatase Inhibition

We generally promote mushroom consumption and mushroom polysaccharide extracts as “immune boosters.” My typical explanation to patients for eating and taking mushroom pills has to do with the whole Natural Killer cell SWAT team story. However, this does not explain the effect seen in these Korean women based on menopausal status. There is another and possibly better explanation for these results: It is all about estrogen and aromatase inhibition.

First, we need to recall a bit of basic biology.

About three-quarters of all breast cancers are hormone sensitive; estrogen makes the tumor cells grow. Blocking estrogen stimulation is a key component in the treatment of these cancers … Think tamoxifen, or flax seeds. The FDA approved tamoxifen in 1977 and it has been the standard of care for treating metastatic breast cancer and in preventing recurrent breast cancer ever since. Tamoxifen binds to estrogen receptors and blocks estrogen from attaching and stimulating the cancer cells. This has made tamoxifen the largest-selling breast cancer treatment in the world. Estimates are that five years of tamoxifen therapy reduces mortality from breast cancer by 31%. Of course, tamoxifen does have its down sides, like increasing risk of endometrial cancer by 2.4 times or thromboembolitic disease by 1.9 times.

Tamoxifen is outdated, and is being replaced rapidly by a new class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors.

Aromatase-inhibiting drugs arrived on the market about ten years ago and have recently replaced tamoxifen as the accepted standard of care in post-menopausal breast cancer patients. Tamoxifen continues to be the standard for premenopausal women. The top three aromatase-inhibiting drugs are anastrozole, exemestane and letrozole.

These drugs have a different mechanism of action than tamoxifen. The estrogen in menopausal women comes from the adrenal glands rather than the ovaries. The adrenal glands secrete androstenedione which is converted into estrogen. Blocking aromatase provides a means to block estrogen production. The drugs used as aromatase inhibitors can reduce estrogen production by 90% to 95%.

Although these new drugs are safer than tamoxifen, they do seem to cause more symptomatic complaints; the most common one I have seen in patients is arthralgia.

The symptoms can be severe enough that some patients refuse to continue treatment with aromatase inhibitors. As much as these drugs provide long-term benefit in treating cancer, some patients cannot tolerate the short-term discomfort. As a result, we have been watching for alternatives, especially reports suggesting that foods might block aromatase action. Here is where we start looping back in order to explain the mushroom story.

Mushrooms as an Aromatase Inhibitor

Dr. Shiuan Chen at the City of Hope in Duarte, Calif., has been publishing research for the last six years on dietary aromatase inhibitors. In his first papers, Chen and his colleagues reported that polyphenols called procyanidin B dimers were aromatase inhibitors. Knowing that grape seeds are a good source of this chemical, he and his group of researchers ran out to their local health food stores and bought every grape seed product they could find. They tested the aromatase inhibition action of 13 brands of grape seed extracts in cell and animal studies and found that ten worked. They published this initial research in December 2003, reporting that grape seed extracts lowered estrogen levels and slowed tumor growth (Eng et al., 2003). They confirmed these early findings in detail in a Cancer Research published paper in June 2006 (Kijima et al., 2006): The grape seed extracts could inhibit aromatase by at least 80%. Chen’s team has begun a Phase I human trial using four doses of grape seed extract, from 50mg to 300mg per day, in women at high risk for developing breast cancer. We await results.

Chen also looked for additional foods that are aromatase inhibitors, and curiously found that white button mushrooms are particularly effective. Other mushrooms, including shiitake and portabella, also are effective, but Chen focused on the white buttons simply because they are easily available (Chen et al., 2006; Grube et al., 2001).

If mushrooms act as aromatase inhibitors, this might explain the Korean effect. It would especially explain why the protection only appears to extend to post-menopausal women. Aromatase inhibition has no effect on estrogen levels before menopause. The “immune boosting” properties may not be why mushrooms help in breast cancer; it may be all about estrogen.

The variety of mushrooms at my local Korean market is overwhelming. Large bags of dried mushrooms are stacked high on forklift pallets. I don’t read Korean, and the English translations on the packages are of little help. The English labels tell me all the bags contain dried “mushrooms.” Some I recognize as shiitake mushrooms. Others are beyond my recognition.

Luckily, esteemed colleague Michael Uzick has studiously perused the text of the original Korean paper with his typical care and informed me that it actually reported which mushrooms Koreans eat most frequently. Their favored mushrooms were (in order of preference): shiitake, oyster and enokitake mushrooms.

Does it matter which kind? Perhaps not, as our common white button mushrooms may be just as effective.

So, how many mushrooms does a menopausal woman need to eat to make a difference?

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that in 2001 the average American ate 3.94 pounds of mushrooms, or about 4.9g/day per capita. Asian Americans ate more mushrooms, averaging 8.9 pounds or about 11.1g/day, more than twice the U.S. national average.

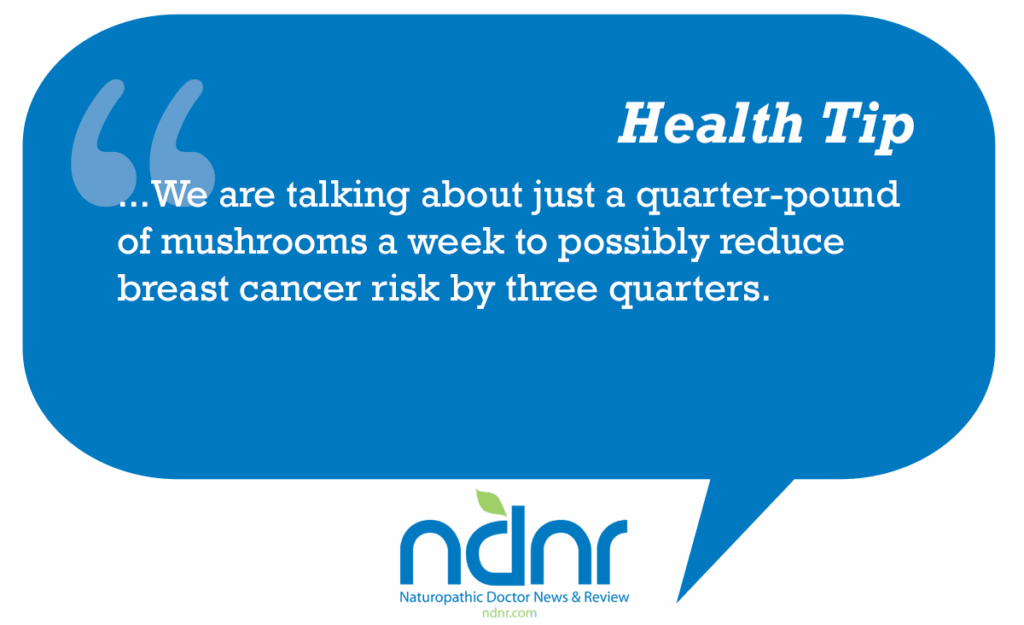

In the Korean mushroom study, participants ate an average 9.6g/day of mushrooms. The women with breast cancer averaged only 7.8g/day, but the control group without breast cancer averaged 11.4g/day. Here comes my version of Math for Dummies: Round up the 11.4g/day to 14-something grams, and call it half an ounce. Then pretend there are eight days in a week. This way you end up with an even four ounces of mushrooms per week as a suggested protective dose. We are talking about just a quarter-pound of mushrooms a week, or about a pound a month to possibly reduce breast cancer risk by three quarters.

Application for Patients

How shall we translate this into practice? We can easily encourage menopausal women to eat loads of mushrooms. This makes sense, unless of course the women are complaining of hot flashes, in which case they might appreciate more aromatase activity and the resultant estrogen.

I do not know if mushrooms or grape seed extracts will prove useful for women taking aromatase-inhibiting drugs. Will adding increase the effect, or has the drug already suppressed aromatase as far as it will go?

Aromatase-inhibiting drugs have their limits. Breast cancer cells eventually become estrogen independent and the estrogen-lowering effect of the drugs no longer slows cancer growth. Could alternating or cycling aromatase-inhibiting drugs with food inhibition slow the development of estrogen-independent tumor cells?

Certainly, there are women who cannot tolerate the side effects of the aromatase inhibitors and refuse to take them. These women may be perfect candidates for dietary aromatase inhibition. Some combination of grape seed extracts and mushrooms may be almost as effective as the current drugs.

Eating mushrooms seems like such a little thing to ask of a patient. There is so much marketing excitement surrounding these aromatase-inhibiting drugs. Each new study on them comparing survival and disease progression statistics that I read lulls me into thinking that the drug companies are finally on to something great. In truth, these data from the mushroom studies are just as exciting, perhaps even more so. It’s the simplicity that fools me. What could be less glamorous than a mushroom?

This story reminds me of many of the other things we do as NDs. By tradition, we favor the simpler, low-tech, low-cost, drugless interventions when searching out treatments. Perhaps we need to add another one of those Latin phrases to our definition of naturopathy: Along with Vis Medicatrix and Tolle Causam and the rest, perhaps we need to define ourselves as the physicians who choose Simplex Res, the simple things. Like that Shaker song …

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO is a 1991 graduate of NCNM and has practiced in Denver for the past 14 years. He served as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Physicians (CANP) from 1992 to 2000, and continues to serve for the organization. He is in practice with his wife, Rena Bloom, ND, at the Denver Naturopathic Clinic.

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO is a 1991 graduate of NCNM and has practiced in Denver for the past 14 years. He served as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Physicians (CANP) from 1992 to 2000, and continues to serve for the organization. He is in practice with his wife, Rena Bloom, ND, at the Denver Naturopathic Clinic.

References

Hong SA et al: A case-control study on the dietary intake of mushrooms and breast cancer risk among Korean women, Int J Cancer Feb 15;122(4):919-23, 2008.

Eng ET et al: Suppression of estrogen biosynthesis by procyanidin dimers in red wine and grape seeds, Cancer Res Dec 1;63(23):8516-22, 2003.

Kijima I et al: Grape seed extract is an aromatase inhibitor and a suppressor of aromatase expression, Cancer Res Jun 1;66(11):5960-7, 2006.

Chen S et al: Anti-aromatase activity of phytochemicals in white button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus), Cancer Res Dec 15;66(24):12026-34, 2006.

Grube BJ et al: White button mushroom phytochemicals inhibit aromatase activity and breast cancer cell proliferation, J Nutr Dec;131(12):3288-93, 2001.