Setareh Tais, ND

“Oh, honey,” She says. “This isn’t something you get over. It’s something you get through, and then you carry it around with you for the rest of your life. It’s part of your story now. Part of your history….” We both sit silently and breathe together. I am grateful for this covenant. For this unexpected moment of understanding and connection…

Excerpt from Heather Swain’s Luscious Lemon1(p269)

The desire to conceive children is powerful, widespread, and expected by most couples; however, for 8-16% of all couples, this bright expectation is extinguished by infertility.2,3 Obstacles to conceiving arise from delayed child-bearing, genetic abnormalities, hormonal imbalance, environmental toxins, infectious disease, poor lifestyle habits, obesity, and other factors. Some couples have the resources and interest to pursue naturopathic or conventional medical interventions, while others may choose to become parents through adoption. It is important to recognize that infertility can cause psychological and sociological distress to individuals and couples, although every patient experiences and copes with infertility in her or his own personal and dynamic way. In order to provide empathy and support to infertile patients and couples, this paper will review the psychological and sociologic distress that is often experienced with infertility.

Lack of Social Support

For many patients, infertility can be an isolating and lonely experience. Initially patients may want to keep their infertility struggles private, but at some point the emotional burden often becomes too heavy and they slowly start confiding in friends and family members. Unfortunately, many patients report a lack of understanding from others,4 or they complain that their peers do not know what to say.5 Leslie Butterfield, a Seattle-based clinical psychologist specializing in infertility counseling, remarks,

“Because the individual’s need to mourn and the cultural sanctions against mourning are in direct conflict, those who grieve have trouble expressing themselves and those who listen have little practice or experience in offering support or condolence.”

Leslie Butterfield6

Not surprisingly, 80% of couples complain of receiving negative or minimizing comments about their infertility,7 such as, “It just wasn’t meant to be,” or “Now you can focus on your career,” or “That’s what happens when you don’t have babies when you are young,” or “All you have to do is start relaxing.” These kinds of negative or minimizing comments invariably come from friends or family members who have not experienced infertility.

Because mourning is a social process, the support and acknowledgement of one’s social network is required for mourning to be complete. Men and women can benefit from the support of a therapist and the camaraderie of a support group of others who understand the emotional toll of infertility. In one survey of infertile couples, patients were asked, “Would you find it useful to have help/guidance from someone other than a medical specialist?” Of the respondents, 39% answered yes, with 7% of these desiring weekly support and 84% preferring monthly support.8 Not surprisingly, it has been shown that infertile couples who participate in an 8-week support group report less depression and psychological distress than couples who receive no support.9 Patients may be referred to RESOLVE, Inc. (www.resolve.org), a national organization providing infertility education and informational resources. The website also features a directory that allows patients to search for the nearest local community infertility support group, that is facilitated by either a lay person or a therapist. RESOLVE, Inc. has also partnered with Redbook to create a video-based infertility awareness campaign called “Truth about Trying.” Patients can watch short videos of lay people, medical professionals, and celebrities talking about their personal infertility struggles, as a way to foster understanding while removing the veil of secrecy and shame that often surrounds the diagnosis of infertility.

Sexual Dysfunction Related to Infertility

Infertility can have a negative impact on intimacy, with couples often equating intimacy with a goal-oriented act of achieving pregnancy.3 Women who are measuring their basal body temperature or using urinary ovulation predictor kits, and men who feel pressured to be intimate during “fertile periods,” may begin to view sexual intercourse as a chore. Studies have shown that infertility is associated with a decrease in libido, anorgasmia and impotence.10,11 After receiving the diagnosis of infertility, 59% of women experience a decrease in intimacy, 49% report being less satisfied with intercourse, and 49% report being less comfortable with their sexuality.12 NDs should address sexual dysfunction and feelings of inadequacy caused by infertility. Patients should be encouraged to experience intimacy for closeness and pleasure, rather than “demand performance” during fertile periods for baby-making only. During counseling, NDs should recognize the value of sexuality, encourage couples to compliment and offer positive feedback to each other, and remind patients to celebrate small sexual pleasures and affection as they rekindle their sex life.

Gender and the Response to Infertility

Research on gender differences in the response to infertility indicates that a woman generally experiences more psychosocial stress in response to the infertility experience, even when the cause is not attributed to her.13,14,15 Women also experience higher rates of stress if they have not received a diagnosis (or cause) of their infertility; therefore, a prudent evaluation should be initiated. Women will generally experience more fluctuations in their emotions than men, with the onset of menses being a difficult time for many women, as it serves as a reminder that conception has not occurred.16 In comparison, men are more likely to experience depression, lower self-esteem and feelings of stigma if they are diagnosed with male factor infertility.17

In addition to different responses to infertility, women and men also cope with infertility in different ways. Women often seek comfort by talking to friends, family members, or a counselor. This method of coping through sharing and expressing emotions seems to lower stress and anxiety.18,19,20 In contrast, when men discuss challenges with conceiving, their reported stress and anxiety levels often increase.20 Men tend to use avoidance and withdrawal as methods for coping; which may be the reason why their global distress levels are higher than those of women.19 In a longitudinal study of infertile men, a man’s coping strategy during the infertility experience was found to have a significant impact on both his long-term adjustment and his likelihood of becoming a father. Men who engaged in nurturing activities such as caring for a garden, pet, or home were more likely to be well-adjusted and achieve fatherhood than men who focused on self-centered activities like body-building.21 In addition to different coping styles, men and women generally have different communication styles wherein women tend to be “pursuers” and men tend to be “distancers.” In the pursuer-distancer relationship, the more one partner presses for communication and togetherness, the more the distancer attempts to create space between them.22(p30) It would be beneficial to discuss these differences with couples during counseling, as this would help foster understanding, bring them closer together, and show them they are not grieving alone.23

Marital Discord and Infertility

Diminished sexual satisfaction coupled with different coping mechanisms for men and women can result in marital distress. Our society does not socialize men towards parenthood to the same degree as women. As a result, men are more likely to forgo fertility treatments and focus on other rewarding activities. The willingness to forgo the pursuit of biological parenthood is often very distressful for wives and partners. Therefore, couples need to discuss how long and how far they are willing to go to conceive. They should also discuss the potential to become parents through adoption or to embrace a childless, albeit fulfilling, future. Studies have shown that couples are better able to cope with infertility when they have increased marital commitment, less denial of their diagnosis, and are able to reframe the problem so that it is more manageable.24

The Emotional Response to Infertility

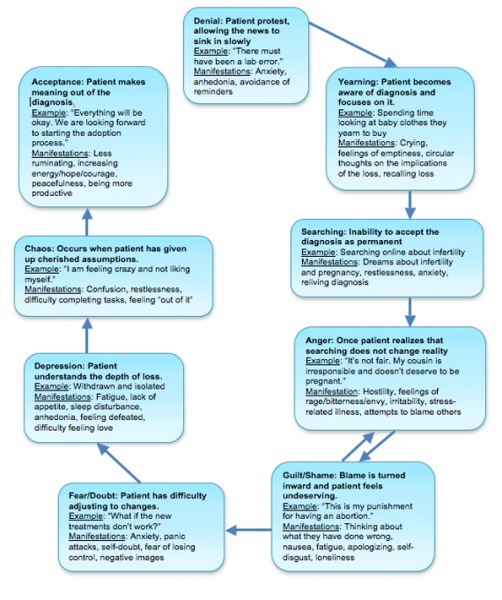

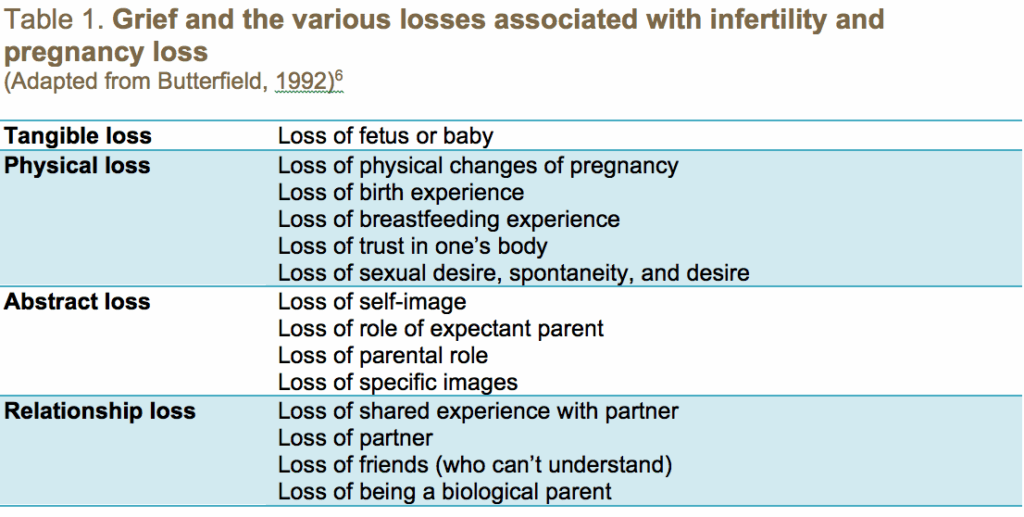

Atwood and Dobkins16 have described the emotional cycle that is experienced with infertility: denial, anxiety, loss of control, guilt and isolation, then acceptance and resolution. Butterfield6 has described her own observations of the emotional response to infertility and pregnancy loss: denial, yearning, searching, guilt/shame, fear/doubt, and chaos/disorganization (Figure 1). She explains that the various stages can occur in any order and not all of them are experienced by everyone. Most couples reach out for help once they are in the grief and isolation stage.16 Sadness is often revisited frequently, but this diminishes the more the patient is encouraged to discuss and explore feelings of loss. In order to properly grieve infertility and pregnancy loss, the various aspects of loss should be brought to awareness and discussed (Table 1). During this time, women may express grief around not having experienced the body changes of pregnancy or experienced labor, giving birth or breastfeeding.5 Women might withdraw from social events like baby showers and children’s birthdays, since they serve as a painful reminder that they cannot have a biological child.16 Couples should receive counseling and explore the pain associated with not being able to conceive biological children. Once a patient can accept the loss of control over her fertility, she will be more able to focus on a resolution.

Naturopathic Recommendations and Conclusions

Patients who are interested in naturopathic or integrative reproductive care can benefit from the compassionate and holistic approach of NDs. As written in A Naturopathic Approach to Intrauterine Inseminations: Conceiving with Compassion,25 Drs Gleisner and Tais describe a compassionate approach to assisted conception: “As naturopathic doctors we can provide our patients with a holistic approach to infertility, create a comfortable and caring environment, and allow partners to participate in the reproductive process.” In providing holistic reproductive care, NDs should be cognizant of the consequences of using negative terminology that may contribute to low self-esteem and feelings of bodily betrayal, such as “incompetent cervix,” “poor ovarian reserve,” and “ovarian failure.” Instead, it would be beneficial to have treatment plans incorporate more positive terminology directed at improving ovarian response, increasing fertile cervical mucus, and enhancing sperm health.

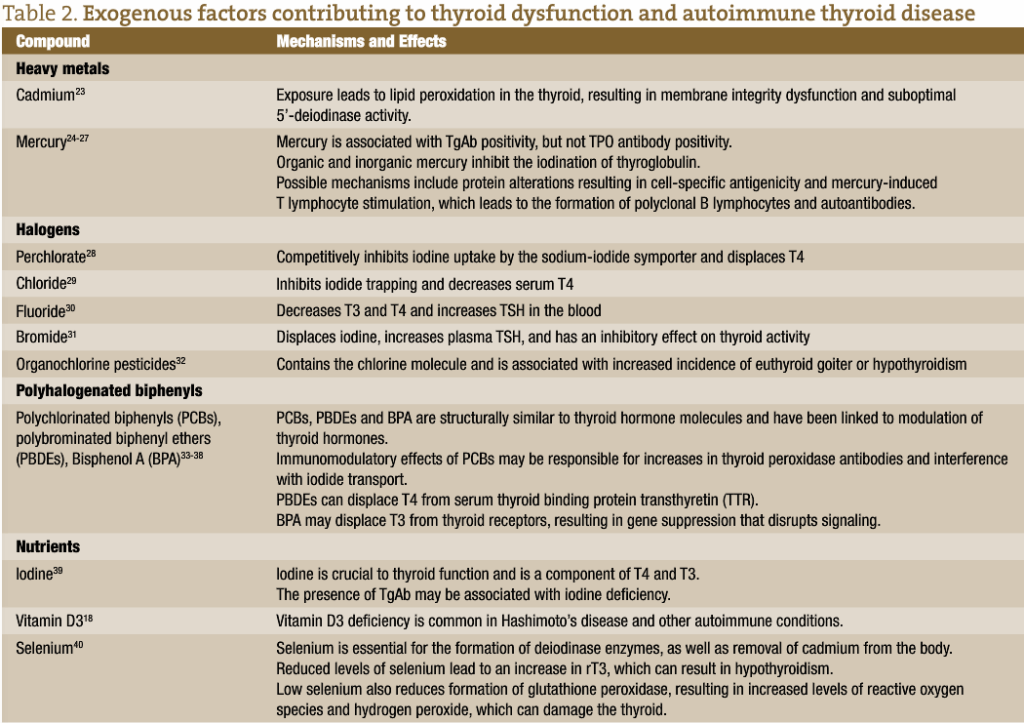

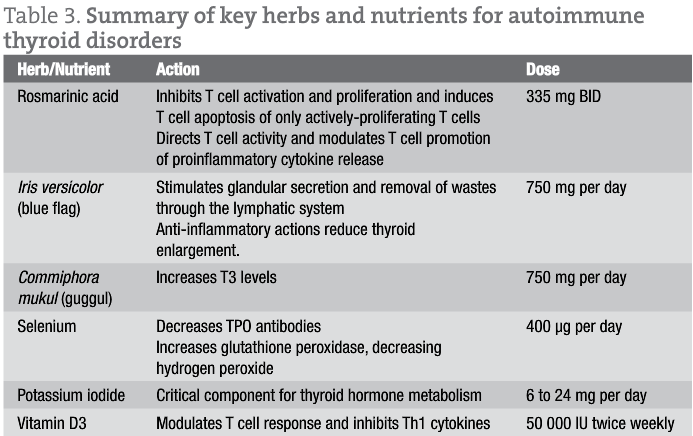

The naturopathic approach to grief counseling and infertility support may also include craniosacral therapy, homeopathy, and herbal medicines (Table 2); however, the benefits of active listening, empathy and counseling should not be underestimated. NDs should bear witness to their patients’ pain and actively listen to their infertility story. NDs can educate patients on the typical or expected emotions that may be experienced, such as anger, sadness, helplessness, and loss of control. Patients should be given an opportunity to discuss the stressful comments they receive from their friends and family members (for example, parents asking, “When are you going to make me a grandparent?”), so that patients can plan ahead how to respond to distressful questions and comments. NDs should be prepared to discuss with patients any tendencies to blame themselves for past medical decisions, such as “This is my fault for getting an abortion in college” or “Did this happen because I took birth control pills?” NDs should address not only the tangible loss of a pregnancy but also the intangible loss of not having experienced the physical and emotional state of being pregnant (Table 1). When counseling patients, explore what is meaningful to the couple/patient, what they have learned about each other or themselves, and what they have gained through their experience. Address any sense of isolation and provide resources for support (Table 3). Highlight their strengths to help them cope with disappointment. Make a connection to another difficult time when they had similar emotions. Discuss how they coped with difficult times in the past and how those coping skills can be used now. Exploring the diverse emotional terrain of infertility and normalizing the infertility experience may ultimately lead patients to resolution and acceptance of losing a once-cherished assumption that parenthood would come without assistance.

Case study 1

A 41-year-old Caucasian woman, gravida 1, para 1, with premature ovarian failure (POF) presents with complaints of hot flashes and oligomenorrhea. She was diagnosed with POF in her early 30s and had been under the care of a reproductive endocrinologist who was hopeful she would conceive her second child through in vitro fertilization (IVF). She had one failed IVF cycle 4 years ago. After listening to her history and current symptoms, I ask her, “What is your goal? What would you like to work on?” The patient begins to cry and expresses gratitude that I did not assume she was interested in becoming pregnant. “I know you specialize in infertility but I thought you could still help me balance my hormones and improve my hot flashes even though I am done trying to get pregnant… It just feels like my doctors are so certain they can help me get pregnant, but I am tired of trying.” During our visits, we discuss the depths of her loss, her acceptance that she has secondary infertility, her goals for the future and her relief that she can redirect her thoughts and resources to other ventures. She is currently doing well on herbal medicines for hormonal balance, with minimal complaints of vasomotor flushes. Her treatment plan also includes nutrients for bone health and an herbal adaptogen formula containing Schisandra chinensis and Crataegus spp. This patient has achieved acceptance of having secondary infertility.

Case study 2

A 35-year-old African-American male presents with low libido and “because his wife made the appointment for him.” Initially the patient is reluctant to discuss his health and he denies sexual dysfunction. After a few visits, he describes depressive symptoms and feeling like a failure. He goes on to explain that during the last 16 months he and his wife have been trying to conceive without success. His sex life has become “mechanical” and frustrating. He completes a semen analysis, which shows significant male factor infertility. The results were reviewed in a gentle but honest manner. The patient experiences sadness, fear of losing control and anxiety. We discuss his sadness, fears, and stress-coping strategies. His treatment plan addresses mental health, dietary modifications, fish oil, antioxidants, and a heavy-metal chelation protocol. During this time, the couple was encouraged to take a 3-month break from trying to conceive, focusing instead on a detoxification program and to have intercourse for fun and closeness only. He reports improvement in depressive symptoms and overall sexual satisfaction. His wife is currently pregnant with the help of naturopathic reproductive care and intrauterine insemination.

Case study 3

A 36-year-old Caucasian female, gravida 0, presents for a second opinion regarding amenorrhea. She was diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian dysgerminoma at age 16 and has since been in remission after treatment with chemotherapeutics and a unilateral oophorectomy. At that time she was put on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for bone protection. One year ago she discontinued her HRT in order to get pregnant but her menses never returned. Her OBGYN has been checking her FSH every 2-3 months (all readings have been between 70 and 76 mIU/mL). She wants to know how long after discontinuing HRT it will take for her FSH “to go back to normal” and her menses to return. She had presented in the denial phase but had been moving into the searching phase (given that she had found my website by searching online for “natural fertility doctor”). The patient was informed that her FSH is significantly elevated and suggestive of premature ovarian failure. She was gently queried on her understanding of the effects of chemotherapy on fertility. She recalls that her oncologists had explained that her treatment would render her infertile but her OBGYN suggested that her amenorrhea was due to being on OCPs and that her FSH may normalize with time. I discuss all of her options for integrative reproductive therapy and motherhood. Naturally she experiences sorrow and emotional chaos, but she is quick to express relief in knowing all her management options and their corresponding success rates. She has chosen to undergo donor egg IVF using her sister’s oocytes.

Setareh Tais, ND is a naturopathic physician practicing general family medicine in Fresno, CA, with a focus on women’s health, pediatrics, and reproductive health. She received her doctorate of naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University and completed a 2-year naturopathic family medicine residency. During her residency, she received additional training in integrative reproductive endocrinology and infertility. She serves on the board of the California Naturopathic Doctor’s Association and participates on the legislative committee. She is also a member of the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians.

References

- Swain H. Luscious Lemon. New York: Downtown Press; 2004.

- Eunpu DL. The Impact of Infertility and Treatment Guidelines for Couples Therapy. Am J Fam Therapy. 1995;23(2):115–128.

- Cooper-Hilbert B. Helping couples through the crisis of infertility. Clinical Update. The American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. 2001;3:1–6.

- Daniluk JC. Reconstructing their lives: A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the transition to biological childlessness for infertile couples. J Couns Dev. 2001;7:439–449.

- Forrest L, Gilbert MS. Infertility: An unanticipated and prolonged life crisis. J Mental Health Counsel. 1992;14(1):42–58.

- Butterfield L. Pregnancy Loss: the Invisible Wound. RESOLVE of Virginia: Infertility Education Advocacy Support. 1992.

- Callan VJ, Hennessey JF. Strategies for coping with infertility. Br J Med Psychol. 1989;62(Pt 4):343–354.

- Edelmann RJ, Connolly KJ. The counselling needs of infertile couples. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1987;5(2):63–70.

- Stewart DE, Boydell KM, McCarthy K, et al. A prospective study of the effectiveness of brief professionally-led support groups for infertility patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(2):173–182.

- Klempner LG. Infertility: Identifications and disruptions with the maternal object. Clin Soc Work J. 1992;20(2):193–203.

- Butler RR, Koraleski S. Infertility: A crisis with no resolution. J Mental Health Counsel. 1990;12(2):151–163.

- Sabatelli RM, Meth RL, Gavazzi SM. Factors mediating the adjustment to involuntary childlessness. Fam Relat. 1988;37(3):338–343.

- Wright J, Duchesne C, Sabourin S, et al. Psychosocial distress and infertility: Men and women respond differently. Fertil Steril. 1991;55(1):100-108.

- Abbey A, Andrews FM, Halman LJ. Gender’s role in responses to infertility. Psychol Women Q. 1991;15(2):295-316.

- Berg BJ, Wilson JF, Weingartner PJ. Psychological sequelae of infertility treatment: The role of gender and sex-role identification. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(9):1071-1080.

- Atwood JD, Dobkin S. Storm clouds are coming: Ways to help couples reconstruct the crisis of infertility. Contemp Fam Ther. 1992;14(5):385–403.

- Natchtigall RD, Quiroga SS, Tschann JM, et al. Stigma, disclosure, and family functioning among parents with children conceived through donor insemination. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(1):1-7.

- Gibson DM, Myers JE. The effect of social coping resources and growth-fostering relationships on infertility stress in women. J Mental Health Counsel. 2002;24(1):68–80.

- Stanton AL, Tennen H, Affleck G, Mendola, R. Coping and adjustment to infertility. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1992;11(1):1–13.

- Williams L, Bischoff R, Ludes J. A biopsychosocial model for treating infertility. Contemp Fam Ther. 1992;14(4):309–323.

- Snarey J, Son L, Kuehne VS, Hauser S. The role of parenting in men’s psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of early adulthood infertility and midlife generativity. Dev Pysch. 1987;23(4):593-603.

- Nichols MP, Schwartz RC. Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Inc; 2010.

- Watkins KJ and Baldo TD. The Infertility Experience: Biopsychosocial Effects and Suggestions for Counselors. J Couns Dev. 2004;82(4):394-402.

- McEwan KL, Costello CG, Taylor PJ. Adjustment to infertility. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(2):108–116.

- Gleisner D, Tais S. A naturopathic approach to inseminations: Conceiving with compassion. Naturopathic Doctor News and Review. October, 2010. https://ndnr.com/web-articles/womens-health/a-naturopathic-approach-to-intrauterine-insemination/