Low Sexual Desire in Women: Perceiving the Whole

Introduction

Sexual dysfunction is a common and exceedingly complex concern experienced by women. It is a source of personal distress, and contributes to poor self-esteem, relationship disruption and decreased quality of life1-3. The complexity and personal nature of this concern is often underappreciated, and ultimately, the multifactorial nature of low libido or desire makes discussion and management of this issue challenging. Examination of female sexual dysfunction is not well-represented in current naturopathic curricula or naturopathic literature, and evidence suggests that this topic is fairly universally neglected4,5. The description of “Female Sexual Dysfunction” in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR) is a reductionist approach to the assessment and management of self-reported sexual distress6-8. Recent research has emphasized that the female sexual response, rather than being a linear model, is a cyclic, multi-faceted and dynamic process with numerous inputs4-9. Naturopathic doctors are well-positioned to not only perceive sexual dysfunction as a complex concern for women, but also to approach management in a way that is sensitive, individualized and holistic. Patient education is often the most efficacious strategy for management4,5,7,10. This article will explore the incidence and impact of sexual dysfunction in females, reconsider its classification, discuss the contributors to low sexual desire, and provide strategies to management of women complaining of sexual dysfunction.

Incidence and Impact

Up to 63% of women experience some degree of sexual dysfunction throughout the lifespan. The most commonly reported concern is low desire1-5,9,11. Women reporting low sexual desire also report frustration, anger and stress, hopelessness, decreased self-esteem and emotional satisfaction, and low happiness1-3; however, it is difficult to know whether correlates are causes or effects of sexual dysfunction. There seems to be minimal correlation with sexual orientation2,12.

Definition

Definition

Masters and Johnson first described the sexual response in 196613. It was then perceived that male and female responses were parallel, with a linear and genitally-focused progression through desire and arousal to orgasm, followed by resolution. The DSM-IV-TR attempt to capture the range of female sexual concerns reflects this definition14. More recent evidence suggests that the female response cycle is a complex process that does not apply well to a linear, genitally-focused model4-9. In fact, the suggestion has been made that decreased desire not be perceived as a disorder, but as a normal part of the female experience3,5,7,8. Ultimately, the defining elements are a change in sexual function associated with personal distress4,6. Distress warrants treatment, not a change in desire per se.

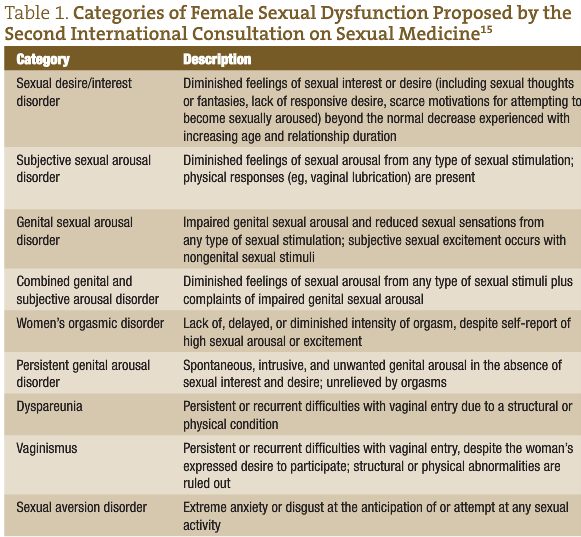

The Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine has attempted to redefine diminished Female Sexual Dysfunction. Table 1 summarizes their recommendations.

Contributing Factors

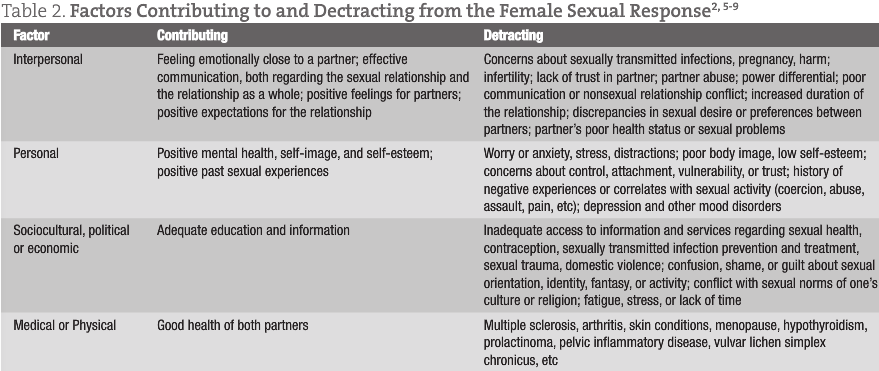

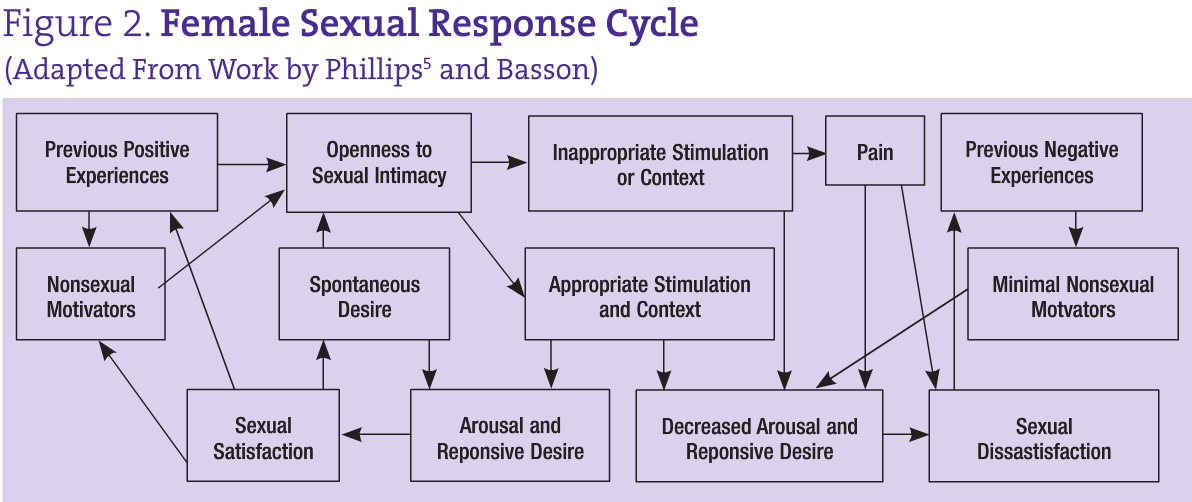

The experience of sexual arousal blends physical and mental/emotional responses and intentions, and many women will describe cyclical and overlapping movement through the response cycle6,7,9. Any condition contributing to physical or emotional discomfort during sexual intimacy can impede interest and should be ruled out. However, the bulk of diminished sexual desire in women is due to complex social, emotional and relationship inputs4-9.

Although some woman report experiencing spontaneous desire, many initiate sexual activity due to non-sexual motivators5-7, such as a desire to foster intimacy with a partner

or to relieve tension. If a woman is open to becoming sexually aroused, she is more likely to enjoy the experience and focus on the sensations7. Previous positive encounters and experiences will also motivate further pursuit of sexual experiences and openness to arousal6,7. Table 2 provides a non-exhaustive summary of factors involved in sexual interest. Figure 2 illustrates the complexity of the sexual response cycle in women.

Assessment

Assessment

A thorough history is essential to explore the cause(s) of the diminished desire, as well as to build rapport. As with any sensitive topic, it is critical to engage in truly active, non-judgmental listening. The use of sensitive, non-biased language leaves space for discussion of possible gender identity or sexual orientation concerns4-6. Although a woman may volunteer her sexual concerns, it can be helpful to screen during a comprehensive review of systems with a question such as, “Many women report a change in sexual desire or function. Are you experiencing any sexual problems or concerns?”4,7

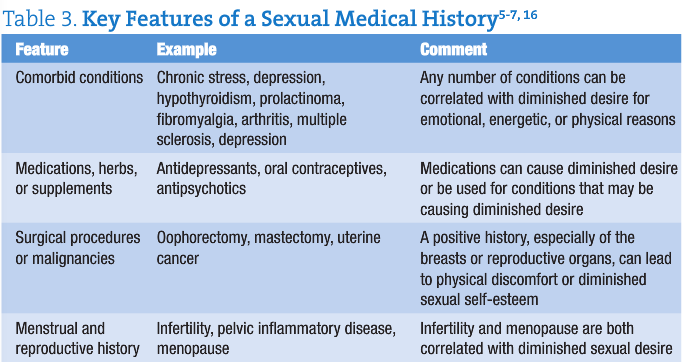

An important priority for assessment is the evaluation of any physical contributors to the concern. Key features of a medical history are highlighted in Table 3.

There are a number of tools that have been validated to assess the presence, nature and degree of female sexual dysfunction1,4,6; however, as a highly individualized concern, it is more useful to emphasize a comprehensive sexual history. Open-ended questions are important, to allow space for personal reflection and communication6. One should start with a description of the sexual concern, including the onset of the concern, the context in which the concern occurs and details of the sexual routine and response6,7. An exploration of her life and relationship context is necessary. Is she currently sexually active? What is the nature of her relationship? How is the communication in her relationship(s)? Does she have other ways of fostering emotional intimacy? Are there concerns around birth control, privacy or transmission of sexually-transmitted infections? What is the nature of her sexual encounters and routines? If she is in a monogamous relationship, it is important to include the partner in the history-taking as well; indeed, obtaining a complete sexual history for both partners is most useful in supporting the couple in their intimate relationship6,7.

A woman’s past sexual experiences have a tremendous impact on her current level of desire. An exploration of both the positive and negative aspects of her sexual past is important, along with family and personal beliefs regarding sexuality. Any history of physical, emotional or sexual trauma or abuse is critical to ellicit5-8.

One overarching strategy is to have the client construct her own personal sexual response cycle based on Table 2 and Figure 1, identifying factors that contribute to or detract from arousal7. This can give both the client and practitioner valuable insight into her understanding of her experience5,7.

Physical exams and laboratory evaluations in cases of diminished desire are often normal5,6,9. However, a careful assessment should be done to rule out any condition that may be contributing to the concern. Any hypotheses raised through history taking should be followed up with a focused physical exam and objective laboratory measures, including a complete pelvic exam5,6,9. The use of a hand mirror during a pelvic exam is an opportunity to provide education regarding normal variations of genital anatomy6.

Approach to management

Because of the highly individual nature of the sexual response cycle, and the myriad of factors that affect a sexual experience, management will be highly individual as well. Barring the treatment of any contributing medical concerns, the focus of management is education3-6,9,10. It can be exceedingly helpful to let women know that diminished desire may not be a dysfunction, but a common and normal response to changing age, relationship, and life context6,8,9. The female sexual response is not linear or solely genitally focused; multiple “peaks” may be reached before orgasm is obtained (if at all), and effective communication, adequate time, and patience are often therapeutic. Many couples find that setting a “date” for sexual intimacy is helpful. Although many women are not aroused at the start of an encounter, intention and openness to the experience often lead to desire and arousal5,7,9. Stress management, adequate rest and energy levels are also important elements to a satisfying sexual encounter. Enhancing non-sexual emotional intimacy between partners is extremely valuable. Working with the couple is essential to ensure education and commitment of both partners9.

A change in routine and approach to stimulation can be beneficial. Experimentation and masturbation can allow a woman to explore her likes and dislikes; the use of erotic toys, and changes in position, timing, location, or type of stimulation (for example, oral or manual) can help an individual or a couple break out of a routine and enhance arousal5,6,9. Because subjective arousal is not necessarily well correlated to genital arousal, the use of a water-based lubricant can decrease physical discomfort that may be interfering with sexual pleasure5,6,9. One technique that can be very beneficial is sensate focusing6,9. This is a process requiring high-level communication between partners, and involves an intentional progression from non-sexual touch to sexual/genital stimulation. The emphasis on culmination in orgasm is removed, placing the focus on sensation, communication and exploration.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy can be helpful to decrease anxiety or maladaptive thought patterns interfering with trust or intimacy during sex. Other types of therapy can be utilized to address deeply-rooted issues such as poor self-image, a history of trauma or control issues9,10. Markovic demonstrates one therapeutic approach to a concern of sexual dysfunction which encompasses many of the factors discussed here10. Although dated, Becoming Orgasmic by Heiman and LoPiccolo is an excellent guided resource for women and couples interested in a holistic approach to improving sexual function, including an emphasis on sensate focus17.

Evidence for biochemical treatment of sexual dysfunction in women is limited. There are no approved mediations, although trials and off-label uses of pharmacotherapy have been attempted to varying degrees of benefit and harm4,6,9. Herbal medicine can be considered for some cases, including maca (Lepidium meyenii, L. peruvianum), horny goat weed (Epimedium sagittatum, E. brevicornum, yin yang huo), Damiana turnera and Gingko biloba16,18,19,20. The use of nervines such Passiflora incarnata may be helpful in cases of anxiety related to sexual intimacy. Hormonal contributors to sexual dysfunction, such as menopausal changes, may be improved through the use of herbs such as Cimicifuga racemosa, Vitex agnus castus or Angelica sinensis16.

While there is much written in the historical Chinese medical texts on excessive and inadequate sexual function in men, and on issues of infertility and menstrual difficulties in women, there is relatively little comment on low sexual desire in women. Consider that healthy sexual desire is dependent on adequate Ministerial Fire, with arousal being yang in nature. Lack of arousal may be seen as a lack of Fire, particularly Kidney-yang21.

Homeopathically, many remedies are useful for diminished sexual desire or arousal. The following rubrics may be worth incorporating into a more complete repertorization:

- Female; coition; aversion to

- Female; coition; enjoyment; absent

- Female; sexual desire; diminished

- Female; sexual desire; wanting

- Female; vaginismus22

Conclusion

Sexual dysfunction is a common and exceedingly complex concern experienced by women. The female sexual response is cyclical, with personal, interpersonal, psychological, social and physical inputs. It may be more therapeutic to consider sexual “dysfunction” as a normal part of the female lifespan, barring medical conditions that may be contributing. Ultimately, management must be initiated in response to personal distress. An open, non-judgmental approach to a sexual history allows a thorough assessment of the concern. Management should be individualized and holistic, emphasizing the treatment of any contributing conditions, and education to both the individual and her partner(s).

Leslie Solomonian, ND is a graduate of CCNM. She completed a two-year residency and is currently an associate professor at CCNM, providing instruction in pediatrics and a ground-breaking integrated clinical diagnostics program. She supervises the clinical practice of fourth year interns at the Robert Schad Naturopathic Clinic and maintains a private eclectic practice in Toronto. Leslie has a keen interest in promoting healthy sexuality in all people and volunteers her time in the community to this end.

Leslie Solomonian, ND is a graduate of CCNM. She completed a two-year residency and is currently an associate professor at CCNM, providing instruction in pediatrics and a ground-breaking integrated clinical diagnostics program. She supervises the clinical practice of fourth year interns at the Robert Schad Naturopathic Clinic and maintains a private eclectic practice in Toronto. Leslie has a keen interest in promoting healthy sexuality in all people and volunteers her time in the community to this end.

References

Learman LA, Huang AJ, Nakagawa S, et al. Development and validation of a sexual functioning measure for use in diverse women’s health outcome studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198(6):710.e1-8; discussion 710.e8-9.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999; 281(6):537-44.

Kellogg-Spadt, S. http://www.nppracticemgt.com/columns/details/whats-so-distressing-about-female-sexual-dysfunction/ (accessed October 15, 2010).

Cox, R, Fye Moore, L. Empowering PAs to ask female patients about their sexual health. Journal of the American Academy of Physician’s Assistants. June 01, 2010. http://www.jaapa.com/empowering-pas-to-ask-female-patients-about-their-sexual-health/article/171462/; accessed October 14, 2010.

Phillips NA. Female sexual dysfunction: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2000; 62(1):127-36.

Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J. Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2008; 77(5):635-42.

Basson R. Women’s sexual dysfunction: revised and expanded definitions. CMAJ. 2005; 172(10):1327-33.

The Working Group on A New View of Women’s Sexual Problems. Female Sexual Dysfunction: A Feminist View. http://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/book/companion.asp?id=12&compID=10. Accessed October 15, 2010.

Basson R. Clinical practice. Sexual desire and arousal disorders in women. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(14):1497-506.

Markovic, D. A Case of Enhancing Sexual Confidence: Both the Client and the Therapist Are the Experts. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 2010; 31(1): 13-24.

Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 112(5): 970-978.

Breyer BN, Smith JF, Eisenberg ML, et al. The impact of sexual orientation on sexuality and sexual practices in North American medical students. J Sex Med. 2010; 7(7):2391-400.

Masters WH, Johnson V. Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.; 1966.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington: The Association; 2000.

Basson R, Wierman ME, van Lankveld J, Brotto L. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2010; 7(1 Pt 2):314-26.

Holt, S. Natural Approaches to Promote Sexual Function Part 2: Stimulants and Dietary Supplements. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 1999; 5(5): 279-285.

Heiman J, LoPiccolo J. Becoming Orgasmic: A Sexual and Personal Growth Program for Women. Fireside; Revised edition. 1987.

Low Dog, T. Smart Talk on Supplements and Botanicals: Maca and Other Herbs for “Sexual Enhancement”. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2009; 15(6):278-280.

Aung HH, Dey L, Rand V, Yuan C. Alternative Therapies for Male and Female Sexual dysfunction. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2004; 32(2):161-173.

Ito T, Trant AS, Lake Plan M. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study of ArginMax, a Nutritional Supplement for Enhancement of Female Sexual Function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2001; 27:541-549.

Maciocia G. Obstetrics and Gynecology in Chinese Medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone. 1998.

Schroyens. Synthesis. Ed. 7.1. London: Homeopathic Book Publishers London and Archibel S.A.; 1998.