Osteoarthritis: A Hormone Deficiency Disorder?

Orthopedics

Angela Cortal, ND

Osteoarthritis (OA) is not only the most common form of arthritis; it is also one of the leading causes of disability among older adults and is the second-most rapidly rising disability-associated disorder. As a result, the “Global Burden of Disease Study 2013” reported OA as a leading cause of chronic pain in the United States and globally.1

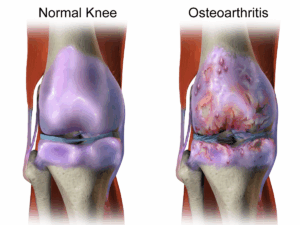

In my 2016 NDNR article, “Halting Osteoarthritis in Its Tracks,”2 in addition to reviewing the epidemiology and pathophysiology of OA, I described how the condition had historically been thought of as a degenerative joint disease simply due to “wear and tear.” Our evolving view of OA includes an understanding that dysfunction in inflammation modulation and mechanical abnormalities (repetitive injuries, acute traumas, or inappropriate joint loading) are additional significant factors in its development.

This article seeks to elucidate the strong connection between sex hormone levels and OA, including risk of development, risk of worsening, and reversal of its pathophysiology.

Testosterone & Osteoarthritis

As an anabolic hormone, adequate levels of circulating testosterone are known to be vitally important for development and maintenance of muscle mass, as well as for having systemic effects on inflammation, wound healing, and inflammatory responses.3 In a study evaluating all-cause chronic knee pain, testosterone levels were inversely associated with knee pain severity.4

Physiologic levels of testosterone, and its correlation to cartilage tissue health, has been a much less appreciated facet, so we will be looking at this in detail.

Physiologic levels of testosterone, and its correlation to cartilage tissue health, has been a much less appreciated facet, so we will be looking at this in detail.

As of 2010, over 600 000 total knee replacements and 300 000 hip arthroplasties were performed annually in the United States,5 which makes them among the most commonly performed orthopedic procedures. In men, the likelihood of undergoing these procedures correlates with circulating levels of anabolic hormones.6 Specifically, those with the highest levels of androstenedione (a testosterone precursor) are at the lowest risk for both total knee replacement and hip arthroplasty. Similar observations have been noted for women: those with higher androstenedione levels have 30% fewer hip replacements.7

A primary finding through the course of development of OA is intra-articular cartilage loss. When patients are categorized as having a severe case of OA, they are often told the joint is “bone on bone,” meaning that the cartilage has so thoroughly degraded, the approximating bones are now in contact. In studies tracking male patients over 2 years via MRI, those with the lowest testosterone levels were found to have accelerated knee cartilage loss (ie, more degradation).8 This finding remained even after controlling for age, body mass index, and bone mineral density – all common confounding factors in OA.

Testosterone is important for everyone’s joints. Although OA is often thought of as a condition exclusive to older adults (due to age-related increased incidence), among women ages 24-45 who are diagnosed with OA, those with the lowest testosterone levels were found to experience a greater degree of arthritic pathology.9

These studies thus far indicate a strong correlation between low testosterone and more severe OA. However, correlation does not equal causation. What do interventional studies show?

First, looking at cartilage cells in culture, we see that application of testosterone to severe osteoarthritic cells directly stimulates the growth and differentiation of cartilage stem cells (called chondrogenic progenitor cells).10 This positive effect was observed in both male and female cartilage cell samples, using physiologic dosages of testosterone – dosing that equates to pre-andropause levels in men, and premenopausal levels in women.

Turning to animal models, studies have demonstrated accelerated development of OA in orchidectomized mice (ie, testicular removal, which causes hypogonadism and thus low testosterone). This intentionally created OA was then reversed to match cartilage levels of non-orchidectomized mice of similar age (the control group).11 This reversal was achieved by supplementation of dihydrotestosterone, a main testosterone metabolite, which exerts many of the secondary sex characteristics we typically attribute to testosterone.

Based on these research findings, testosterone injections have even been successfully performed intra-articularly at the site of degenerative joint disease in human patients to stimulate immune processes and chondrocyte activity necessary to address the osteoarthritis process.12

The research clearly suggests that healthy testosterone levels are necessary for both osteoarthritis prevention and correction.

Estrogen & Osteoarthritis

Estrogen levels in women are also an important aspect of cartilage health, to the extent that some experts have proposed specific OA classification subtypes including estrogen-related OA: “type I OA, genetically determined; type II OA, estrogen hormone dependent; and type III OA, aging related.”13

In addition to the well-established positive effects of maintaining bone mineral density and muscle mass and function, estrogen has also been shown to have the following intra-articular effects14:

- Increases proteoglycan production in chondrocytes

- Decreases cartilage damage in animal models

- Decreases anti-type II collagen serum levels in mice [type II collagen is the predominant type in cartilage]

Similar to the associations between testosterone levels and orthopedic procedure prevalence mentioned earlier in this article, women with higher estrogen levels have been shown to have a 30% reduced risk for total knee replacements.7

One study showed women with serum estradiol (E2) levels in the lowest tertile to have an almost 2-times greater risk of developing knee OA as compared to women whose E2 levels are in the middle tertitle.15 Another study confirmed that in women with knee OA, serum E2 correlates with synovial E2.16

The exact cellular mechanisms at play continue to unfold. Two major factors appear to be the estrogen-induced inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) – a primary driver of collagen degradation17 – and estrogen stimulation of collagen growth and differentiation.18 In essence, estrogen appears to both halt processes that cause cartilage cell death and to activate those pathways that enhance new cell growth.

Estrogen’s inhibition of MMP has been found to promote a substantial 50% reduction in the rate of cartilage destruction.19 Recent research, published in January of 2019, suggests that an additional physiologic effect of estrogen (specifically the metabolite, 2-hydroxyestrone) on cartilage degradation is via arachidonic acid pathway modulation, affecting activity of lipoxygenases and thus leukotriene production and effects.20

Estrogen replacement used to address climacteric symptoms is known to be most effective when begun close to the perimenopausal timeframe, and the same is seen when estrogen is used to address OA-related damage.21 While the OA process can be decades in the making, arresting cartilage loss in perimenopause, before the decline in endogenous estrogen levels causes it to accelerate, is strongly recommended.

Conclusion

This article is not meant to suggest that hormone replacement therapies are indicated for every patient with osteoarthritis. My aim in sharing this information is to inspire you to consider sex hormone deficiencies as a possible contributory factor when working with your OA patients. Prompt identification and treatment of such deficiencies will go a long way toward improving health outcomes of your patients with OA. Reduced pain and improved physical function and quality of life for our patients are goals we can all get behind.

References:

- Moradi-Lakeh M, Forouzanfar MH, Vollset SE, et al. Burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990-2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1365-1373.

- Cortal A. Halting Osteoarthritis in Its Tracks. NDNR. 2016;12(9).

- Adelson H, Moore T, Anderson P. Autologous Stem Cell Therapy: A Naturopathic Approach for the Treatment of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions Part I of II. The Pain Practitioner. 2015;25(3):48-51.

- Jin X, Wang BH, Wang X, et al. Associations between endogenous sex hormones and MRI structural changes in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(7):1100-1106.

- Daigle ME, Weinstein AM, Katz JN, Losina E. The cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review of published literature. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(5):649-658.

- Hussain SM, Cicuttini FM, Giles GG, et al. Relationship between circulating sex steroid hormone concentrations and incidence of total knee and hip arthroplasty due to osteoarthritis in men. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(8):1408-1412.

- Hussain SM, Cicuttin FM, Bell RJ, et al. Incidence of total knee and hip replacement for osteoarthritis in relation to circulating sex steroid hormone concentrations in women. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2144-2151.

- Hanna F, Ebeling PR, Wang Y, et al. Factors influencing longitudinal change in knee cartilage volume measured from magnetic resonance imaging in healthy men. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(7):1038-1042.

- Sowers MF, Hochberg M, Crabbe JP, et al. Association of bone mineral density and sex hormone levels with osteoarthritis of the hand and knee in premenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(1):38-47.

- Koelling S, Miosge N. Sex differences in chondrogenic progenitor cells in late stages of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1077-1087.

- Ma HL, Blanchet TJ, Peluso D. Osteoarthritis severity is sex dependent in a surgical mouse model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(6):695-700.

- Ravin T. The use of testosterone and growth hormone for prolotherapy. J Prolotherapy. 2010;2(4):495-503.

- Herrero-Beaumont G, Roman-Blas JA, Catañeda S, Jimenez SA. Primary osteoarthritis no longer primary: three subsets with distinct etiological, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(2):71-80.

- Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S. Largo R, Herrero-Beaumont G. Osteoarthritis associated with estrogen deficiency. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(5):241.

- Richette P, Laborde K, Boutron C, et al. Correlation between serum and synovial fluid estrogen concentrations: comment on the article by Sowers et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):698; author reply 698-699.

- Sowers MR, McDonnell D, Jannausch M, et al. Estradiol and its metabolites and their association with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2481-2487.

- Claassen H, Steffen R, Hassenpflug J, et al. 17β-estradiol reduces expression of MMP-1, -3 and -13 in human primary articular chondrocytes from female patients cultured in a three dimensional alginate system. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;342(2):283-293.

- Tanamas SK, Wijethilake P, Wluka AE, et al. Sex hormones and structural changes in osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;69(2):141-156.

- Karsdal MA, Bay-Jensen AC, Henriksen K, Christiansen C. The pathogenesis of osteoarthritis involves bone, cartilage and synovial inflammation: may estrogen be a magic bullet? Menopause Int. 2012;18(4):139-146.

- Hafsi K, McKay J, Li J, et al. Nutritional, metabolic and genetic considerations to optimise regenerative medicine outcome for knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(1):2-8.

- Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Lane NE, et al. Association of estrogen replacement therapy with the risk of osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(18):2073-2080.

Angela Cortal, ND, graduated from NUNM in 2012. Her practice focuses on regenerative injection therapies (prolotherapy and platelet-rich plasma injections) and hormonal imbalances, particularly as they impact chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Dr Cortal’s private practice is based in Salem, OR, with a satellite practice in Portland (www.rosecityhealth.com). She also enjoys writing, speaking, and teaching on the topics of regenerative injection therapies and hormonal dysfunction. Dr Cortal is on the board of Santiam Community Health, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit which expands the reach of prolotherapy through mobile health “pop-up clinics” to those with medical and financial barriers to accessing traditional healthcare services (www.santiamhealth.org).

Angela Cortal, ND, graduated from NUNM in 2012. Her practice focuses on regenerative injection therapies (prolotherapy and platelet-rich plasma injections) and hormonal imbalances, particularly as they impact chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Dr Cortal’s private practice is based in Salem, OR, with a satellite practice in Portland (www.rosecityhealth.com). She also enjoys writing, speaking, and teaching on the topics of regenerative injection therapies and hormonal dysfunction. Dr Cortal is on the board of Santiam Community Health, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit which expands the reach of prolotherapy through mobile health “pop-up clinics” to those with medical and financial barriers to accessing traditional healthcare services (www.santiamhealth.org).