Epicenter and Oasis of Naturopathic Innovation

Sussanna Czeranko, ND

Whoever has not himself tried it and convinced himself of it can have no conception of how refreshing, vitalizing and strengthening the effect of the earth is on the human organism at night during rest.

-W. Young, 1904, p.69

To reach Jungborn you ride 38 miles by train and get off when the brakeman calls “Butler”. Just over the hill Jungborn is found: a steep, rocky hill, with a curving bridge path leading across two brooks, each crossed by a rail-less bridge of rough timbers. The traveller has arrived at the place of great peace.

-Ada Peterson, 1906, p.183

Separate sections of the sixty acres are set apart for the sexes, where the greatest freedom from dress restrictions may be enjoyed. Men and women meet at meal time and in the evenings, but at other times each one goes his or her own sweet way, unmolested and unafraid.

-Austin Shaw, 1911, p.147

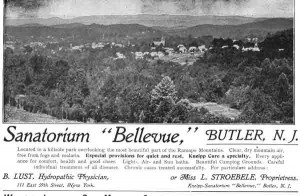

In 1896, Louisa Stroebele opened her secluded “Sanatorium Bellevue” that was embraced by the beautiful forests and slopes of the Ramapo Mountains, near a quaint, little borough of Butler, New Jersey (Figure 1). Within 5 years, this health retreat evolved into a bustling epicenter of naturopathy, steered by what would also grow into one of the most powerful personal and professional life partnerships that naturopathy would ever witness – the team of Louisa and Benedict Lust. Coincidently, in the very same year, an ocean away near another small town, Stapelburg, Germany, located in the Harz Mountains, Adolf Just published his first edition of Return to Nature, to celebrate the opening of his own Jungborn. (Just, 1903, p.ix) Just described the German Jungborn as “a model institution for the true natural life, where those who wish to make arrangements for such a life at home in their own gardens can find the pattern.” (Just, 1901, p.9) In the final chapter of his book, Just left behind a blueprint for anyone to replicate a Jungborn wherever he or she may live.

Figure 1. Sanatorium “Bellevue”; 1901

In 1900, Benedict Lust published a list of 9 such natural healing centers in America. This preliminary list documented several notable and influential pioneers who shaped early naturopathy. These included the “New York Kneippianum,” for example, an elegant and spacious palatial building; the “Badekur,” operated by the esteemed John and Sophia Scheel (from whom Lust acquired the name “Naturopathy” to galvanize the emerging natural health movement); the “Light and Water-Cure Institute” of Ludwig and Carola Staden; the sanitarium developed by Professor F. W. Rittmeier, who used Kneipp and Priessnitz as his models, as well as Kuhne’s methods; and, of course, Miss Louisa Stroebele’s “Bellevue.” And, there were others besides, all of whom followed in Kneipp’s footsteps. (Lust, 1900, p.79) Many of the designers and directors of these sanitariums were apostles of the Kneipp water-cure; however, Carola Staden specialized in gynecology and followed Thure-Brandt’s work, notably his massage for women. In this group we count, too, the efforts of Sophia Scheel, a noted homeopath.

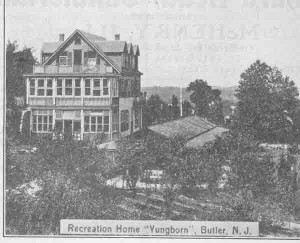

Before Benedict Lust began publishing the work of Adolf Just, most of the early healing centers were called “sanitariums” or “water-cure institutes.” However, with the translation of Just’s book, and with it the availability of the template to build a Jungborn, huge transformations to an emerging health movement began to unfold through the continuous issues of The Naturopath and Herald of Health. In 1901, though, 1 auspicious event over-rode all others. “On Tuesday, the 11th of June, [1901] there was celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Fifth Avenue, New York, the wedding ceremony between Mr. B. Lust of New York and Miss A. [Aloesa] Stroebele of Bellevue, Butler, N. J.” (Editorial Staff, 1901, p.163) The significance of this marriage to the profession is remarkable. The combined energy of this husband and wife team began to resonate immediately. In the following month, a 3-page infomercial announced the “Prospectus of the New York Naturopathic Institute and College” to be located at 135 East 58th St, New York, as well as the launching of the repurposed “Bellevue Sanitarium,” characterized by an explosion of new therapeutic offerings and options, and renamed “Jungborn,” in Butler, New Jersey. (Lust, 1901, p.197) (Figure 2) Previously, the industrious, innovative Louisa Stroebele had operated the Bellevue, relying upon the work of Sebastian Kneipp and his water-cure therapies, as well as on the fresh air naturalist, Arnold Rikli, who discarded clothing in pursuit of fresh air and sunshine. Now, in 1901, the patient coming to the Butler Jungborn would benefit from all of what Louisa had made available before, along with a plethora of new choices in natural health care.

Figure 2. Recreation Home “Yungborn”; 1910

Kneipp Cure and Return to Nature

Jungborn guests arrived with every imaginable complaint. The mission of the Jungborn was “to cure or relieve as much as possible chronic patients of all kinds, by the application of the Natural Method of Healing, employing only Air, Light, Water, Electricity, Magnetism, Hypnotism, Massage, Gymnastics and Rational Diet”. (Lust, 1901, p.198) It is interesting to pause to decipher the previous sentence. “Natural Method of Healing” implies that Lust was referring to the work of Friedrich Eduard Bilz, who studied under Sebastian Kneipp and was the founder of an immense facility comprised of numerous palatial buildings housing his Bilz Sanatorium in Dresden, Germany. Bilz published an encyclopedic, 2-volume health guide of 2074 pages, entitled The Natural Method of Healing, with phenomenal success. In early naturopathic history, Kneipp dominated the therapeutic interventions used in America by the emerging nature-cure healers. In 1900, Lust was just beginning to introduce the work of Adolf Just in his journals, but by 1903 Lust had Just’s book, Return to Nature, ready for sale in an English translation. Lust’s admiration for Just and his work continued throughout his entire life and influenced almost 50 years of his publishing career. While Benedict Lust was alive, there were advertisements for the book Return to Nature in practically every single issue of his various naturopathic journals.

There were no drugs found at the Jungborn. Lust states, “We do not believe in curing one disease by producing another; we remove the cause of the disease and so get rid of it entirely.” (Lust, 1901, p.198) Fresh air, plenty of exercise outdoors, sunshine, an octo- lacto- vegetarian diet of fresh vegetables and fruits, nuts, dairy and farm fresh eggs comprised the fare for those staying at the Jungborn. Guests had other dietary options such as the “frugivorous diet” advocated by Louis Kuhne, the raw food diet, and also complete fasting.

Another key element of natural healing available at Jungborn was the focus on removing from the body its toxic impurities. Lust states, “The depurative organs, and these alone, must do all the work of purification, and there are ways to aid them, which have no bad effects.” (Lust, 1901, p.197) The “Spring Cure” that focused upon dietetics was combined with the other therapies popular at the Jungborn to restore health. Lust explains, “Spring fever, ‘that tired feeling,’ and other spring ailments that have been brought on by lack of exercise, stuffed rooms and a wrong diet during the winter months, are also amenable to quick treatment and cure at this time.” (Lust, 1907, p.139) Many testimonials point out that Jungborn was a perfect place to do a spring cleanse. One guest to the Butler Jungborn exclaimed, for example, “All the year round enthusiasts may be found [at the Jungborn] enjoying its restful quiet, its closeness to Nature, and the healthful ozone that laden with the aroma of its pines and cedars bring ‘healing on its wings’.” (Shaw, 1911, p.146)

There was an abundance of water therapies at the Jungborn. Every imaginable bath could be experienced there; full, half, trunk, hip, partial bath plus full vapor or steam baths, steam jets and steam compresses were utilized. The cold wet sheet compresses or wraps in every variation were available, as well as the signature treatment used by Kneipp – the gush. As well, there were douches of all kinds waiting for patients.

Light- and air- baths were conducted in the open air or under electric lights. Nude bathing was a regular feature in a visitor’s schedule, with 1 session in the morning and a second in the afternoon, followed by bathing in the brooks and swimming areas. Men and women had their own secluded and private area called the “air- and light- park” for enjoying air- and sun- baths in the garb of Nature. “Each park is within a pine boarded stockade ten feet high, and no casual visitor is allowed within the sacred precincts.” (New York Press, 1905) Shaw describes, “Separate sections of the 60 acres are set apart for the sexes, where the greatest freedom from dress restrictions may be enjoyed.” (Shaw, 1910, p.147) The guests at the Lusts’ and Just’s Jungborns “live and sleep in charming and friendly little air and light houses, which are not huts and … stand fully in the open air, surrounded by shrubs and trees.” (Just, 1910, p.712) These air- and light- houses were constructed with 2 rooms, “one room for each guest so that each room is fully free at three sides… They are provided at all sides with blinds, windows, air-valves, which can at every time be kept open or closed.” (Just, 1910, p.712)

All Manner of Resources: Earth, Electricity, Massage and More

Adolf Just’s earth-cure compresses, baths, barefoot walking, and sleeping outdoors on the earth to expose the body to the earth’s magnetic current were cornerstone treatments. Many relished the earth baths and their healing magnetism. Lust claimed that earth baths “were probably taken by every patient.” (Lust, 1913, p.789) Visitors to the Butler Jungborn were encouraged to sleep on the ground to capitalize on the earth’s electrical forces. People would marvel at how deeply rested they felt after sleeping on the earth. As Young noted, “Just argues that this electrical connection is much more complete when the entire body is in direct contact with the earth.” (Young, 1904, p.69) Even so, in their enthusiastic quest for all manner of natural tools to enhance health and healing, the naturopaths who looked to the “earth” for healing energy were also excited by the new arrival of electricity. They explored with enthusiasm inductive electricity, as well as faradic and galvanic currents in the delivery of massages and treatments.

Among all these options at the Jungborn, important emphasis was placed on providing non-invasive treatments for women. It must be remembered that women a century ago were mutilated, often experiencing excruciating pain as a result of fashions such as the corset. In addition to restful “earth” sleep, baths and more, the Thure-Brandt gynecological massage helped relieve pelvic displacements and inflammation. Massage was freely available with “attendants at the service of the patients for purpose of rubbing and stroking the body by way of applying and transferring human curative power and animal heat in the most natural and effective manner.” (Lust, 1913, p.789) Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Lust cautioned that massage must be provided with skill and care, and with particular attention to the specific needs of individual patients. In any case, there was an abundance of physical care at the Jungborn, including exercise. As a case in point, Swedish gymnastics and resistant exercises were readily available.

In addition to the physical therapies, there was a conscious effort to encourage spiritual awareness at the Jungborn. Lust states, “The significance of powerful spiritual influences (brotherly love, trust in God, etc.) are greatly taken into consideration and such influences are promoted.” (Lust, 1913, p.790) The body and mind paradigm factored hugely among those visiting the Jungborn and was evidenced by the liberal views expressed. Often discussions and lectures were offered in the evenings by visiting scholars and writers.

A Typical Day

A typical day at the Butler Jungborn began at sunrise with men going to their secluded park and women to theirs. Women would rise at 6 AM with the sun and make their way to the brook to splash water on their faces. “All of the women were barefoot.” (Patterson, 1906, p.185) There was much to occupy the women at the brook, walks in the sandy soil, bathing until the breakfast bell rang at 7 AM. Breakfast consisted of bread, fruit, water, or cocoa or barley coffee substitute. Following breakfast and all other meals, a ritual was observed in which people would repose before engaging in the nature activities available at the Jungborn. Paterson remarks, “Two hours followed in the tents or on the veranda, hours of enjoying the deep silence of the green woods for those who chose to flock alone, and of light-hearted chat for the more gregarious humans.” (Paterson, 1906, p.185) (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Air Tents at Butler

Following the after-meal rest period, women would follow Louisa Lust to the women’s secluded pool area of the brook. Women disrobed before heading off to the brook. Once there, Mrs Lust “permitted no sudden plunging into the stream.” (Paterson, 1906, p.185) Rather, women gradually exposed their feet and then their legs to the cold water and then dashed water onto their backs and breasts before bathers were at liberty to plunge fully into the pool. There were no towels for drying the body; instead, women would exercise in the sun and use the elements of air and sun to dry themselves.

Following the after-meal rest period, women would follow Louisa Lust to the women’s secluded pool area of the brook. Women disrobed before heading off to the brook. Once there, Mrs Lust “permitted no sudden plunging into the stream.” (Paterson, 1906, p.185) Rather, women gradually exposed their feet and then their legs to the cold water and then dashed water onto their backs and breasts before bathers were at liberty to plunge fully into the pool. There were no towels for drying the body; instead, women would exercise in the sun and use the elements of air and sun to dry themselves.

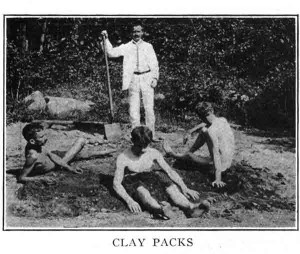

Following the water baths came the earth baths. Women dug out their own pit in the red clay and would cover each other with the cool earth. In one account, a woman felt that worms and bugs were crawling all over her body, to which Louisa Lust responded by explaining in the kindest tones that these sensations were simply the earth’s magnetic forces. “No, no,” [Louisa Lust] answered soothingly, “What you feel is the magnetism of the earth currents passing through your body.” (Paterson, 1906, p.185-186) By and large, Louisa’s influence on others was filled with compassion and confidence. Paterson continues, “To look into our hostess’s dark eyes is to believe whatever she may tell one.” (Paterson, 1906, p.186) Two and one-half hours passed and the noon dinner bell rang, and everyone retreated barefooted and now dressed to the common dining hall for dinner. A sample noon meal consisted of “celery, sliced dried figs, peaches, pears, corn on the cob, mashed potatoes mixed with stewed cabbage, whole wheat bread, peanut butter, and honey cape pudding.” (Paterson, 1906, p.186)

Men, alternatively, rose with the crows of the rooster and would usually embark upon a hike for a mile or so through “a fragrant woods and up hills to the summit of the Cat’s back Mountains, the top of Yungborn’s sixty acres”. (Shaw, 1911, p.150) The descent from the summit led to the men’s secluded camp where they could plunge their perspiring bodies into the running brook. Like the women, towels were not used and instead air and sun would dry them. Following the hike and cold water bath, men would walk barefoot for about 30 minutes before the breakfast bell at 7 AM. After breakfast, options included reading or visiting friends until the prompt 8:30 bell, calling the men to their morning exercises. Shaw explains, “We have a strenuous program of every kind of rhythmic motion which the expert and gentlemanly teacher has devised, and for half an hour we pose and turn and swing our comfortably-clad bodies, breathing deeply, filling the lungs to their limit with the sweet mountain air.” (Shaw, 1911, p.151)

Figure 4. “Harden Your Body” Ad; 1914

Following the exercise routine, activities for the men would include the “lightening spray” which would leave the skin red as a lobster. The lightening spray used cold water under pressure and would leave the sensation of blood surging wildly through all the arteries and veins. Then would come 2 hours of sun and air bathing in the men’s park. Shaw describes this phase in the morning routine: “We will lie on the grass awhile. We will try the mud baths and cover our bodies with their healing magnetism.” (Shaw, 1911, p.151) (Figure 5) The brook was used to wash the mud from the bodies and swim before the dinner bell rang at noon. After a dinner of soup, every variety of vegetables, unpolished rice, a variety of nuts, and desserts, men along with the women would retire for an hour before dividing into groups to return to their respective parks at 2 PM, “where you repeat the sun and air baths of the morning. Take your choice of recreative games, ball or quoits or bowling in the big gymnasium.” (Shaw, 1911, p.152) People often repeated mud baths in the afternoon and there was lots of swimming. At 5:30, the call for breathing exercises brought people together for a half an hour before the 6:00 supper bell. Supper was abundant and vegetarian. People were encouraged to eat slowly, counseled always that “thorough mastication [would] prevent over-feeding.” (Shaw, 1911, p.152)

Figure 5. Mud Therapy at Yungborn; 1911

To Bed With the Chickens

To Bed With the Chickens

Evenings were filled with lectures, music or games in the parlor, a stroll to Butler for entertainment, or walks on the Jungborn grounds. Shaw loved his time at Jungborn, commenting, “Your new found friends have much of interest in common to talk about; there isn’t an instant when the time drags heavily.” (Shaw, 1911, p.154) At 8 PM, women would meet to “take their nightcap of herb tea” (Shaw, 1911, p.155) and men were welcome to join. The day came to a close at 9 PM, with all of the lights turned off. Jungborn residents went to sleep early. The morning always came so soon with another day of healthy fun and activity.

The literature about Jungborn resounds with the enthusiastic endorsements of its visitors, many of whom came again and again. Even a century ago, the need for an oasis from the urgency and stress of urban life was clearly present in the lives of Americans. That Jungborn guests came to an epicenter of naturopathic treatment and reflection may not have been top of mind as they enjoyed restored vigor and calm in their lives; however, the treatments and protocols quickly became legend in naturopathic circles. Naturopathic doctors from far and wide came to Benedict and Louisa Lust’s center of naturopathic care to experience it themselves, to assist in the care and guidance of the guests, and to absorb the energy and magic of this incubator of a medical system which to this day values what is naturally enduring.

References:

Unknown author. (1906). An Adam and Eve community within 40 miles of New York. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VII (3), 117-120. This article was taken from the New York Press, August 20, 1905, and reprinted in B. Lust’s journal.

Editoral Staff. (1901). Wedding bells. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (5), 163.

Just, A. (1901). Return to Nature. 1st edition translation by Benedict Lust. 124 E. 59th St, New York: B. Lust Publishing.

Just, A. (1910). The new paradise of health. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XV (12), 711-721.

Lust, B. (1900). Natural healing in America. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (5), 79.

Lust, B. (1901). Prospectus of the NY Naturopathic Institute and College and Sanitarium Jungborn. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (7), 197-199.

Lust, B. (1907). The spring cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VIII (5), 139-140.

Lust, B. (1913). The Yungborn, Butler, N. J. and Tangerine, Fl. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XIII (11), 789-790.

Peterson, A. (1906). How a New Jersey colony has forsaken clothes and seeks health from earth, sun, air and water. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VII (5), 183-186.

Shaw, J. A. (1911). J. Austin Shaw explains Yungborn nature cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVI (3), 145-155.

Young, C. W. (1904). Return to nature. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (3), 66-69.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.