Exploring how chronic stress, inflammation, and the gut-brain-hormone connection influence sperm quality—and how integrative, mind-body interventions can restore reproductive vitality in men.

Abstract

This article examines male infertility through a psychoneuroimmunological lens, highlighting how stress, inflammation, gut microbiome imbalance, and epigenetic changes impair sperm function. It also reviews evidence-based naturopathic and mind-body strategies that support hormone balance, immune health, and fertility restoration.

The State of Fertility

Male infertility represents a significant and growing public health concern in the United States. According to recent national data, approximately 11.4% of men ages 15-49 experienced some form of infertility between 2015 and 2019 1, with current estimates suggesting approximately 9% of men of reproductive age currently face fertility challenges.2 Male factors contribute to roughly 50% of all infertility cases––being solely responsible in 20-30% and a contributing factor in another 30-40%.3 These statistics point to an often-overlooked reality: male reproductive health significantly impacts the fertility of couples seeking to conceive.

The question of whether sperm counts are declining is up for debate. While several high-profile meta-analyses between 2017 and 2022 suggested global sperm counts had declined by 50-59% since 1973 4, with acceleration after 2000 to 2.64% annually,5 a 2024 systematic meta-analysis in Fertility Sterility analyzing 75 studies of 11,787 U.S. men found no significant changes in sperm concentration among fertile or unselected American men over a 53-year period.6

In recent years, researchers are focusing on functional fertility: the capacity to achieve conception regardless of raw sperm count. Sperm quality parameters including motility (movement), morphology (shape), and DNA integrity may be declining even when concentration remains stable. Preliminary findings suggests the fertility crisis may not be due to sperm count specifically, but rather issues in sperm functionality, driven by lifestyle factors, obesity, environmental toxins, chronic inflammation, and psychosocial stress-mechanisms.7

Clinical Case

A couple– wife aged 26 and husband aged 29– presented to a fertility clinic seeking in vitro fertilization (IVF) after unsuccessfully trying to conceive for three years. The male partner had a history of tobacco use and worked as a farmer with occupational exposure to agricultural pesticides. The female partner had no significant health concerns, no known fertility issues, and demonstrated normal testing including hormonal profiles and regular menstrual cycles. Both appeared to be in good general health, with neither reporting a history of thyroid dysfunction, diabetes, pre-existing medical conditions, or family histories of fertility problems.

The male patient’s semen analysis revealed severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia: 80% of sperm were nonmotile, and 98% demonstrated structural defects with abnormal morphology. Sperm concentration measured only 10 million/mL (reference ≥16 million/mL), total motility was 20% (reference 40-43%), and only 2% exhibited normal morphology (reference 3.9-4.0%).

Hormonal evaluation showed elevated luteinizing hormone (8.0 mIU/mL), suppressed testosterone (1.78 ng/mL), and elevated estradiol (58 pg/mL)-a pattern consistent with environmental toxin exposure and endocrine disruption affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

Table 1: Baseline semen analysis parameters

| Semen parameters | Result | Reference value |

| Ejaculatory abstinence | 3 days | 2-7 days |

| Volume | 1.4 ml | 1.4-5 ml |

| Appearance | Grey opalescent | Grey opalescent |

| pH | 7.2 | 7.2-7.8 |

| Sperm count | 10 million/ml | ≥ 16million/ml |

| Total sperm motility | 20% | 40-43% |

| Morphology | 2% | 2.9-4.0% |

Table 2: Baseline hormone testing

| Semen parameters | Result | Reference value |

| LH mIU/ml | 8.0 mIU/ml | 0.8-7.6 mIU/ml |

| Testosterone ng/ml | 1.78 mIU/ml | 2.50-9.50 mIU/ml |

| Progesterone ng/ml | 0.7 ng/ml | 0.27-0.9 ng/ml |

| Estradiol pg/ml | 58 pg/ml | 20-55 pg/ml |

| FSH mIU/ml | 1.22 mIU/ml | 1.5-12.4 mIU/ml |

| Prolactin ng/ml | 18 ng/ml | <20 ng/ml |

Given the potential links between male factor infertility and occupational pesticide exposure and chronic stress, clinicians implemented an integrative treatment approach prior to proceeding with assisted reproductive technology.

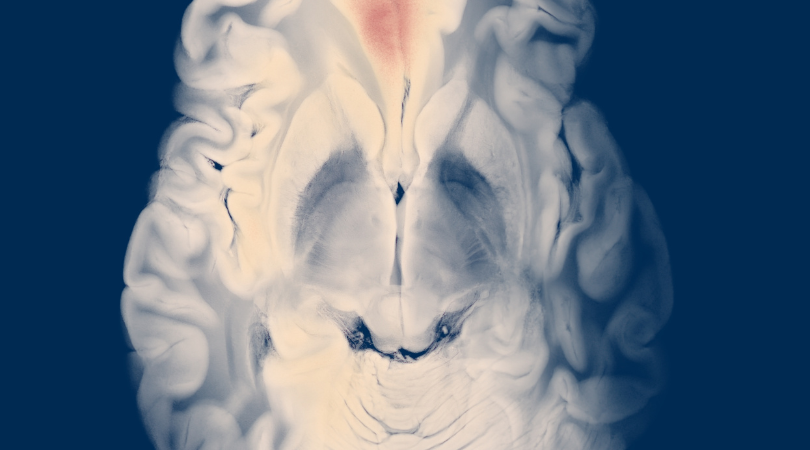

Introducing: Fertility Through a Psychoneuroimmunological Lens

By examining the intricate communication between the brain, immune system, and endocrine systems, the field of psychoneuroimmunology offers a fresh perspective on male infertility. Although the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis remains central to this network, prolonged stress simultaneously disrupts several regulatory systems. Chronic stress alters sperm quality and molecular “blueprints,” potentially influencing children’s brain development and metabolism.8

It also triggers three interrelated biological disturbances:

- Resistance to cortisol (the body’s stress hormone)

- Persistent inflammation, marked by elevated IL-6 and TNF-α

- Disrupted reproductive signaling

Stress suppresses pulses of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)– the signal that initiates testosterone and sperm production– reducing Leydig cell hormone output and weakening Sertoli cell support for sperm maturation.9 Elevated cortisol further blunts the pituitary’s response to GnRH, particularly in the presence of estradiol. 10 This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: cortisol suppresses the hormones that stimulate testosterone, while low testosterone can no longer effectively regulate the stress response, reinforcing reproductive dysfunction. 11

The Microbiota-Gut-Immune-Brain-Gonadal Axis

Perhaps the most revolutionary insight in contemporary psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) research involves the gut-brain-fertility axis, a complex communication network linking psychological stress to reproductive outcomes through the gut microbiome.12

Chronic stress activation disrupts the healthy balance of gut bacteria (dysbiosis) 13, reducing production of beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids and antioxidants while allowing harmful bacteria to overgrow. This imbalance weakens the intestinal barrier, allowing bacterial toxins called lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to leak into the bloodstream.14 These are the same toxins found in elevated levels in individuals with neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s disease.14 These toxins trigger body-wide inflammation that reaches the testicles, where immune cell infiltration and oxidative damage directly impair sperm production.15

Emerging data reveal a protective pattern: individuals with high stress resilience exhibit distinct gut microbial signatures associated with reduced inflammation and stronger gut barrier integrity.16 This microbiome-mediated resilience appears to buffer against stress-induced fertility decline through multiple pathways: balancing sex hormone levels in the bloodstream, improving insulin sensitivity, protecting the immune-privileged environment of the testicles, and even influencing the local bacterial communities within reproductive tissues.17

The gut microbiome also controls the metabolism of tryptophan-the building block for both serotonin (the mood neurotransmitter) and melatonin (the sleep hormone).18 When gut bacteria are imbalanced, this disrupts both the body’s daily hormonal rhythms and the testicles’ antioxidant defense systems, creating a cascade of fertility-compromising effects.19

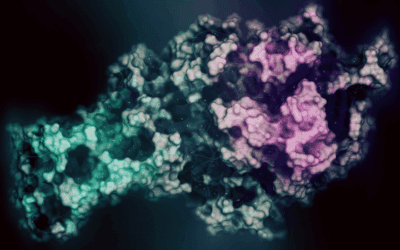

Epigenetic Reprogramming

A noteworthy advancement in stress-related male infertility involves exploring sperm epigenetic reprogramming– the process by which a father’s psychological experiences become molecularly encoded in his sperm and potentially transmitted to his children. Emerging research demonstrates that men with histories of childhood trauma or current severe depression display altered chemical markers on their sperm DNA and changes in small regulatory molecules called microRNAs. 20

These epigenetic modifications are not random– they cluster around genes that control brain development, including genes linked to mood regulation and the formation of dopamine-producing neurons in developing embryos.21 In high-stress individuals, researchers observed 19-21% reductions in these chemical markers, suggesting that a substantial proportion of sperm within a single ejaculate carry stress-induced signatures that may influence offspring neurodevelopment and metabolic health.22

How does stress “reprogram” sperm? The mechanism involves a communication system in the epididymis- the tube where sperm mature after leaving the testicles. When a male experiences significant stress, cells lining the epididymis alter their function and release tiny bubble-like structures called extracellular vesicles (EVs). This response occurs 2-3 months after the stressful event.23 These EVs contain modified microRNAs and proteins that are absorbed by sperm as they pass through, essentially “tagging” them with stress-related molecular information.

When researchers exposed normal sperm to these stress-modified EVs in the laboratory, the sperm changed their energy metabolism and absorbed the stress-related molecular cargo changes that persisted through fertilization and influenced how genes were expressed in the resulting embryos.23

This suggests that paternal stress exposure doesn’t just affect sperm quality; it may alter the biological information passed to the next generation, with potential implications for offspring brain development, stress response, and metabolic regulation.

Depression, Not Anxiety

While both depression and anxiety involve dysregulation of the body’s stress response system (the HPA axis), recent large-scale research reveals an important distinction: depression specifically-rather than generalized anxiety-correlates with measurable declines in sperm quality.24

Men with moderate-to-severe depression show 9.13% lower progressive motility (the percentage of sperm swimming forward effectively), 11.14% reduced total motility (overall sperm movement), and a striking 47.71 million/mL decrease in sperm concentration compared to non-depressed men. These effects are significantly amplified in men sleeping fewer than seven hours nightly.24 Anxiety, by contrast, showed minimal association with sperm parameters except at severe levels.24

This distinction likely reflects differing biological patterns: depression is characterized by chronically elevated inflammatory markers (proinflammatory cytokines)25 and persistently dysregulated cortisol levels, whereas acute, transient anxiety involves more short-term activation of the “fight-or-flight” nervous system without the same degree of sustained inflammation.26

Sleep deprivation appears to worsen depression’s effects on fertility by further disrupting stress hormone regulation and suppressing testosterone production.27 This occurs partly through phoenixin, a brain signaling molecule that controls reproductive hormone activity, which becomes depleted under conditions of chronic stress and insufficient rest.28

Integrative Psychoneuroimmunological Interventions

Given these multilayered mechanisms, effective integrative naturopathic treatment includes addressing: neuroendocrine regulation, immune homeostasis, and epigenetic integrity simultaneously through evidence-based integrative modalities.

Mind–Body Neuroimmune Modulation

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) exert measurable effects on psychoneuroimmune pathways relevant to fertility. An 8-week mindfulness meditation protocol delivered significantly reduced depression and anxiety scores in individuals undergoing fertility treatment.29 Mechanistically, MBIs downregulate NF-κB-mediated inflammatory gene expression, reduce circulating IL-6 and C-reactive protein, normalize diurnal cortisol rhythms, and potentially reduce oxidative stress markers including seminal reactive oxygen species.29

Brief daily practices (such as 10-20 minutes) appear sufficient to recalibrate prefrontal-limbic connectivity and dampen sympathetic overactivation.30 Importantly, mindfulness reduces physiological stress markers including cortisol and inflammatory cytokines31 — mechanisms directly relevant to preserving sperm quality during chronic stress exposure.

Microbiome-Targeted Nutritional Psychiatry

Therapeutic restoration of gut eubiosis represents a novel fertility-enhancing strategy.12 Dietary patterns emphasizing prebiotic fiber (targeting production of butyrate and propionate), fermented foods containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum, and polyphenol-rich botanicals (green tea catechins, pomegranate ellagitannins) facilitate microbial diversity and anti-inflammatory metabolite production.32

Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA/DHA at 2-3 g/day) reduce systemic IL-6 while enhancing testicular expression of antioxidant enzymes including glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase.33 This dual action-systemic immune modulation combined with local testicular protection exemplifies the psychoneuroimmune principle of multi-level intervention.

Targeted Nutraceutical Epigenetic Support

Specific compounds demonstrate capacity to mitigate stress-induced oxidative damage while potentially supporting healthy epigenetic programming. Coenzyme Q10 (200-300 mg/day) improves sperm motility and DNA integrity34 by enhancing mitochondrial electron transport efficiency and reducing oxidative injury to sperm membranes and chromatin.35

Melatonin emerges as a particularly promising psychoneuroimmunological agent given its multifunctional roles: circadian HPA axis regulation,36 direct antioxidant activity exceeding vitamin E,37 immunomodulation through cytokine regulation,38 and protection of sperm DNA and mitochondrial integrity during heat or oxidative stress.39 Doses of approximately 3-6 mg nightly not only may improve sleep patterns but may also improved tryptophan metabolism and enhance seminal antioxidant capacity.39

Combined antioxidant protocols, such as L-carnitine (2 g/day) and acetyl-L-carnitine (1 g/day),41 and selenium (200 mcg/day), zinc (30 mg/day), vitamins C (500 mg twice daily) and E (400 IU/day), demonstrate consistent improvements in sperm concentration, motility, and morphology across 3-6 month intervention periods, with effect sizes greatest in men with elevated baseline oxidative stress markers.40

Psychotherapeutic Neuroendocrine Recalibration

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) reduce proinflammatory cytokine expression42 and can contribute to normalization of testosterone:cortisol ratios through enhancement of emotion regulation circuitry involving prefrontal-amygdala connectivity.43 Eight to twelve weekly sessions addressing cognitive distortions, behavioral activation, and stress appraisal modification effectively improve depressive symptoms, 44 thus creating conditions for reproductive hormone restoration.

Clinical Application: Integrative Medicine Success

The principles of psychoneuroimmunology translate directly into clinical results, as shown in our 2024 Cureus case study.45 In that report researchers hypothesized that a 29-year-old man’s pesticide exposure and symptoms matched patterns of toxin-driven hormone disruption and stress-related HPG axis dysfunction. His treatment protocol included a combination of traditional Ayurvedic interventions with lifestyle modification over four months:

- Shilajit 50 mg daily for 90 days (a traditional adaptogenic mineral supplement with documented antioxidant and spermatogenic properties)

- Panchakarma therapy including intraurethral uttar basti (Ayurvedic detoxification) 3-5 days per month for 4-5 months

- Reduction of pesticide exposure and lifestyle counseling

Post-treatment semen analysis revealed remarkable improvements:

- Sperm count increased 160% from 10 to 26 million/mL

- Total motility increased 125% from 20% to 45% (now within normal range)

- Morphology improved 650% from 2% to 15% normal forms

- Volume slightly increased from 1.4 to 1.5 mL

Table 3: Post-treatment semen analysis parameters (4 month follow up)

| Semen parameters | Result | Reference value |

| Ejaculatory abstinence | 3 days | 2-7 days |

| Volume | 1.4 ml | 1.4-5 ml |

| Appearance | Grey opalescent | Grey opalescent |

| pH | 7.2 | 7.2-7.8 |

| Sperm count | 26 million/ml | ≥ 16million/ml |

| Total sperm motility | 45% | 40-43% |

| Morphology | 15% | 2.9-4.0% |

The couple subsequently achieved successful pregnancy through IVF and pregnancy was confirmed with β-hCG of 973 mIU/mL.45

This case illustrates that by addressing environmental toxins, enhancing detox pathways, and using adaptogens, even severe male infertility may improve. The 7.5-fold increase in normal sperm morphology highlights the potential of integrative approaches targeting oxidative stress, hormone balance, and inflammation to enhance or restore fertility in toxin-exposed men.

Concluding Remarks

Psychoneuroimmunology reframes male infertility from a single-gland disorder to a whole-body condition driven by interconnected biological systems. This framework is particularly pertinent for men who may be experiencing one or a combination of symptoms related to: depression, sleep deprivation, chronic inflammation, stress hormone imbalances, gut microbiome disruption, and changes in sperm at the molecular level.

For naturopathic clinicians, this understanding supports the use of integrated strategies:

- Mind-body practices to recalibrate stress responses

- Diet, prebiotics, and probiotics to restore gut microbiome balance

- Antioxidants and adaptogens to protect cells from oxidative and inflammatory damage

- Psychotherapy to address mood disturbances and chronic stress

The integration of psychoneuroimmunology and reproductive medicine shows that fertility reflects overall health and resilience. Evidence-based strategies that support mental, immune, and reproductive balance can help restore vitality where mind, immunity, and fertility meet.

Nicole Cain, ND, is the only physician in the U.S. with both a masters in Clinical Psychology and a naturopathic medical degree. Dr Cain focuses on homeopathic approaches to psychiatric illness, as well as integrative treatments for mental health. She has expertise in bipolar disorder and psychiatric illness in adolescents & young adults. To learn more about Dr Cain, visit: www.drnicolecain.com.

References

- Nugent CN, Chandra A. Infertility and Impaired Fecundity in Women and Men in the United States, 2015–2019. National Health Statistics Reports. 2024; (202):1–35. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published April 24, 2024. Accessed October 16, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr202.pdf

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. How common is infertility? National Institutes of Health. Updated 2025. Accessed October 16, 2025. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/common

- Prabakar P, Buch JP, Sinha S. Male Infertility. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Updated 2025 Jul 2. Accessed October 16, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562258/

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Sperm counts may be declining globally, review finds, adding to debate over male fertility. CNN Health. Published November 15, 2022. Accessed October 16, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/research-news/17742/

- Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Jolles M, Pinotti R, Swan SH. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of samples collected globally in the 20th and 21st centuries. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(2):157–176. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmac035. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36377604/

- Lewis K, Cannarella R, Liu F, Roth B, Bushweller L, Millot J, Kuribayashi S, Kuroda S, Aguilar Palacios D, Vij SC, Cullen J, Lundy SD. Sperm concentration remains stable among fertile American men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2025;123(1):77–87. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.08.322. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39128669/

- Sciorio R, Tramontano L, Adel M, Fleming S. Decrease in sperm parameters in the 21st century: obesity, lifestyle, or environmental factors? an updated narrative review. J Pers Med. 2024;14(2):198. doi:10.3390/jpm14020198. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10890002/

- Tuulari JJ, Bourgery M, Iversen J, et al. Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with specific epigenetic patterns in sperm. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30:2635–2644. doi:10.1038/s41380-024-02872-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-024-02872-3#citeas

- Odetayo AF, Akhigbe RE, Bassey GE, Hamed MA, Olayaki LA. Impact of stress on male fertility: role of gonadotropin inhibitory hormone. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;14:1329564. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1329564. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10801237/

- Estradiol enables the direct pituitary actions of cortisol to suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-induced LH secretion in ovariectomized hypothalamo-pituitary disconnected (HPD) ewes during the breeding season. Biol Reprod. 2007;77(suppl 1):184. doi:10.1093/biolreprod/77.s1.184. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314983502_ESTRADIOL_ENABLES_THE_DIRECT_PITUITARY_ACTIONS_OF_CORTISOL_TO_SUPPRESS_GONADOTROPIN-RELEASING_HORMONE_GnRH-INDUCED_LH_SECRETION_IN_OVARIECTOMIZED_HYPOTHALAMO-PITUITARY_DISCONNECTED_HPD_EWES_DURING_THE

- Xiong X, Wu Q, Zhang L, et al. Chronic stress inhibits testosterone synthesis in Leydig cells through mitochondrial damage via Atp5a1. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26(2):354–363. doi:10.1111/jcmm.17085. Erratum in: J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27(20):3213–3214. doi:10.1111/jcmm.17829. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8743653/

- Moustakli E, Stavros S, Katopodis P, et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis and its impact on reproductive health: mechanisms and clinical applications. Metabolites. 2025;15(6):390. doi:10.3390/metabo15060390. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12195147/

- Warren A, Nyavor Y, Beguelin A, Frame LA. Dangers of the chronic stress response in the context of the microbiota-gut-immune-brain axis and mental health: a narrative review. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1365871. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1365871. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11096445/

- Kalyan M, Tousif AH, Sonali S, et al. Role of endogenous lipopolysaccharides in neurological disorders. Cells. 2022;11(24):4038. doi:10.3390/cells11244038. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9777235/

- Bacterial LPS mediated acute inflammation-induced spermatogenic failure in rats: role of stress response proteins and mitochondrial dysfunction. Inflammation. 2010;33(4):235–243. doi:10.1007/s10753-009-9177-4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41089714_Bacterial_LPS_Mediated_Acute_Inflammation-induced_Spermatogenic_Failure_in_Rats_Role_of_Stress_Response_Proteins_and_Mitochondrial_Dysfunction

- Delgadillo DR, Borelli JL, Mayer EA, et al. Biological, environmental, and psychological stress and the human gut microbiome in healthy adults. Sci Rep. 2025;15:362. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77473-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-77473-9#citeas

- Ashonibare VJ, Akorede BA, Ashonibare PJ, Akhigbe TM, Akhigbe RE. Gut microbiota-gonadal axis: the impact of gut microbiota on reproductive functions. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1346035. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1346035. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10933031/

- Miyamoto K, Sujino T, Kanai T. The tryptophan metabolic pathway of the microbiome and host cells in health and disease. Int Immunol. 2024;36(12):601–616. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxae035. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11562643/

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky H, Zhou JR. Gut microbiota dysbiosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and epigenetic alterations in metabolic diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13(8):985. doi:10.3390/antiox13080985. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11351922/

- Wang Y, Chen ZP, Hu H, et al. Sperm microRNAs confer depression susceptibility to offspring. Sci Adv. 2021;7(7):eabd7605. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd7605. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7875527/

- Lossi L, Castagna C, Merighi A. An overview of the epigenetic modifications in the brain under normal and pathological conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3881. doi:10.3390/ijms25073881. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11011998/

- Tuulari JJ, Bourgery M, Iversen J, et al. Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with specific epigenetic patterns in sperm. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30:2635–2644. doi:10.1038/s41380-024-02872-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-024-02872-3#citeas

- Moon N, Morgan CP, Marx-Rattner R, et al. Stress increases sperm respiration and motility in mice and men. Nat Commun. 2024;15:7900. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-52319-0. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11391062/

- Zhang Y, Chen ZP, Wang Y, et al. Association between mental health and male fertility: depression, rather than anxiety, is linked to decreased semen quality. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1478848. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1478848. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11581891/

- Paira, D. A., Silvera-Ruiz, S., Tissera, A., Molina, R. I., Olmedo, J. J., Rivero, V. E., & Motrich, R. D. (2022). Interferon γ, IL-17, and IL-1β impair sperm motility and viability and induce sperm apoptosis. Cytokine, 152, 155834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2022.155834 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043466622000436

- Sic A, Cvetkovic K, Manchanda E, Knezevic NN. Neurobiological implications of chronic stress and metabolic dysregulation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Diseases. 2024;12(9):220. doi:10.3390/diseases12090220. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11431196/

- Lateef OM, Akintubosun MO. Sleep and reproductive health. J Circadian Rhythms. 2020;18:1. doi:10.5334/jcr.190. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7101004/

- Friedrich T, Stengel A. Current state of phoenixin—the implications of the pleiotropic peptide in stress and its potential as a therapeutic target. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1076800. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1076800. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9968724/

- Buric I. Psychoneuroimmunology of mindfulness: what works, how it works, and for whom? Brain Behav Immun Health. 2025;46:101022. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2025.101022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12155858/

- Mora Álvarez MG, Hölzel BK, Bremer B, et al. Effects of web-based mindfulness training on psychological outcomes, attention, and neuroplasticity. Sci Rep. 2023;13:22635. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48706-0. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-48706-0#citeas

- Calderone A, Latella D, Impellizzeri F, de Pasquale P, Famà F, Quartarone A, Calabrò RS. Neurobiological changes induced by mindfulness and meditation: a systematic review. Biomedicines. 2024;12(11):2613. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12112613. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591838/

- Ma X, Shin YJ, Jang HM, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum alleviate colitis and cognitive impairment in mice by regulating IFN-γ to IL-10 and TNF-α to IL-10 expression ratios. Sci Rep. 2021;11:20659. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00096-x. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-00096-x#citeas

- Moustafa A. Effect of omega-3 or omega-6 dietary supplementation on testicular steroidogenesis, adipokine network, cytokines, and oxidative stress in adult male rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5570331. doi:10.1155/2021/5570331. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8260291/

- Salvio G, Cutini M, Ciarloni A, Giovannini L, Perrone M, Balercia G. Coenzyme Q10 and male infertility: a systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(6):874. doi:10.3390/antiox10060874. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8226917/

- Alahmar AT, Calogero AE, Singh R, Cannarella R, Sengupta P, Dutta S. Coenzyme Q10, oxidative stress, and male infertility: a review. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2021;48(2):97–104. doi:10.5653/cerm.2020.04175. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8176150/

- Huang Y, Xu C, He M, Huang W, Wu K. Saliva cortisol, melatonin levels and circadian rhythm alterations in Chinese primary school children with dyslexia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(6):e19098. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019098. https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/fulltext/2020/02070/saliva_cortisol,_melatonin_levels_and_circadian.51.aspx#:~:text=Cortisol%20is%20the%20main%20end,individual%20behavior%20and%20cognitive%20function.

- Korkmaz A, Reiter RJ, Topal T, Manchester LC, Oter S, Tan DX. Melatonin: an established antioxidant worthy of use in clinical trials. Mol Med. 2009;15(1-2):43–50. doi:10.2119/molmed.2008.00117. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2582546/#:~:text=A%20number%20of%20studies%20have,to%20garlic%20oil%20(72).

- Zheng N, Long Y, Bai Z, et al. Melatonin as an immunomodulator in CD19-targeting CAR-T cell therapy: managing cytokine release syndrome. J Transl Med. 2024;22:58. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04779-z. https://translational-medicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12967-023-04779-z#citeas

- Liu QQ, Li X, Li JH, et al. Melatonin improves semen quality by modulating oxidative stress, endocrine hormones, and tryptophan metabolism of Hu rams under summer heat stress and the non-reproductive season. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025;14(6):630. doi:10.3390/antiox14060630. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40563265/

- Bouhadana D, Godin Pagé MH, Montjean D, Bélanger MC, Benkhalifa M, Miron P, Petrella F. The role of antioxidants in male fertility: a comprehensive review of mechanisms and clinical applications. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025;14(8):1013. doi:10.3390/antiox14081013. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12383105/

- Balercia G, Regoli F, Armeni T, Koverech A, Mantero F, Boscaro M. Placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial on the use of L-carnitine, L-acetylcarnitine, or combined L-carnitine and L-acetylcarnitine in men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(3):662–671. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16169400/

- Järvelä-Reijonen E, Puttonen S, Karhunen L, et al. The effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention on inflammation and stress biomarkers: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2020;27(5):539–555. doi:10.1007/s12529-020-09891-8. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7497453/

- Liu T, Li D, Shangguan F, Shi J. The relationships among testosterone, cortisol, and cognitive control of emotion as underlying mechanisms of emotional intelligence of 10- to 11-year-old children. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:273. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00273. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6928062/

- Prasartpornsirichoke J, Pityaratstian N, Poolvoralaks C, Sermruttanawisith N, Polpakdee K, Pholphet K, Buathong N. Effects of online cognitive behavioral therapy on depression, negative automatic thoughts, and quality of life in Thai university students during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2021: a quasi-experimental study. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1502406. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1502406. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1502406/full

- Mathiya P, Nair N, Singh B, More A, Pareek C. Integrative approach to address male infertility: a case study on organophosphorus compound exposure and traditional medicinal interventions. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62697. doi:10.7759/cureus.62697. https://www.cureus.com/articles/259053-integrative-approach-to-address-male-infertility-a-case-study-on-organophosphorus-compound-exposure-and-traditional-medicinal-interventions.pdf

Dr. Nicole Cain ND, MA, EMDR, is a Naturopathic Physician in Arizona, with a Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology, specializing in trauma-informed, integrative mental health for anxiety, panic, and mood disorders. She is the author of the acclaimed book Panic Proof, a leading expert on the gut-brain axis and psychoneuroimmunology, and is a consultant, speaker, and podcaster focusing on empowering clinicians and the community with integrative and holistic wellness solutions. Dr. Nicole’s work has been featured at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health conferences, the PsychANP, in Forbes, The Huffington Post, Oprah Magazine, Tamron Hall, Katie Couric Media, Salon, NPR, Harvard Business Review, Psychology Today, and others.