Sara Love, ND

A clinician’s guide to when—and when not—to use A. muciniphila: evidence for gut-barrier support, metabolic and immune effects, pasteurized vs live formulations, and patient selection.

Abstract

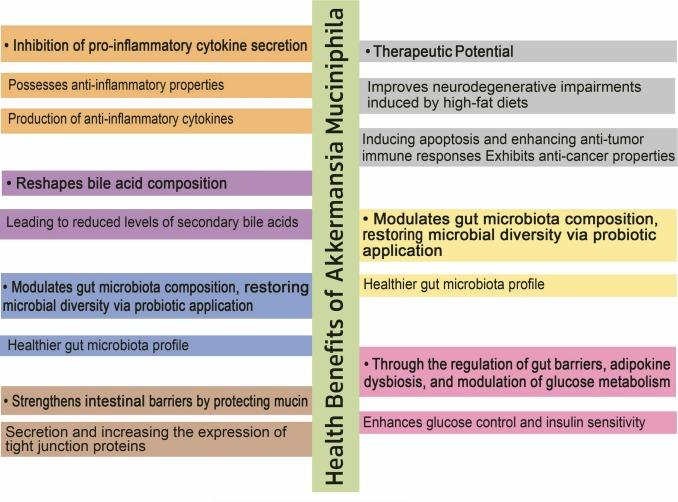

Akkermansia muciniphila is an emerging “next-generation” probiotic with data supporting improvements in intestinal integrity, metabolic markers, and immune modulation. This article reviews potential benefits, safety considerations, contexts to avoid use, and practical guidance on choosing pasteurized vs live preparations.

Introduction

The human gut microbiome has emerged as a key regulator of health and disease. The more we learn about the different species that live in the microbiome, the better we can target probiotic therapies for patients. Akkermansia muciniphila, an oval-shaped, anaerobic, Gram-negative, mucin-degrading bacterium, has been touted as a “wonder probiotic” and is actively marketed directly to consumers with celebrity spokespeople. A. muciniphila colonizes a considerable portion of the human gut microbiome starting early in life; from the first year onward, its levels become equal to those of healthy adults, then decrease in the elderly.¹ A. muciniphila comprises 1–4% of the fecal microbiota of healthy adults. Its primary functions—strengthening gut barrier integrity, improving metabolism in various ways, and modulating immunity—have been supported by both preclinical and clinical research. However, A. muciniphila is not indicated for all individuals; taking a clinical history along with a gut microbiome evaluation may provide more specific, individualized recommendations for a targeted approach to a patient’s overall health. A. muciniphila has been studied and is commercially available in both live and pasteurized formulations.

Benefits

Gut Barrier and Anti-Inflammatory Effects

A. muciniphila strengthens intestinal integrity by stimulating mucin production and enhancing tight-junction proteins such as ZO-1 and occludin, thereby reducing intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation.¹ Both live and pasteurized preparations have been shown to reduce inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, while live bacteria additionally induce IL-10—an anti-inflammatory mediator—through the outer membrane protein Amuc_100² and extracellular vesicles (EVs), while suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines.³ This research was conducted in murine studies and has not yet been replicated in large-scale human studies.

Metabolic Health

Animal models consistently demonstrate improvements in obesity-related parameters, including reduced body weight, lower fasting glucose, and improved glucose tolerance following supplementation.³ In a randomized clinical trial involving 40 overweight or obese adults, daily supplementation with either pasteurized or live A. muciniphila for 3 months improved insulin sensitivity (+28%), reduced insulinemia (−34%), lowered total cholesterol (−8.7%), and modestly decreased body weight and fat mass.⁴ Individuals with higher baseline A. muciniphila displayed greater improvements in insulin sensitivity markers and other clinical parameters. Meta-analyses further confirm benefits for glycemic control, lipid metabolism, and liver function markers.⁵

Immune Modulation

A. muciniphila modulates host immunity by producing a unique lipooligosaccharide that signals via Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), promoting anti-inflammatory IL-10 production.⁶ This immunomodulatory effect suggests a role in controlling systemic and gut inflammation. Since A. muciniphila levels are diminished in many inflammatory diseases, it could be speculated that its absence during inflammation prevents immune suppression at the mucosal epithelial border. Cross-talk between A. muciniphila and the host might affect immunological tolerance and homeostasis within the gut, possibly by keeping the immune system alert for potential disruptions.⁶

Liver Health

Preclinical evidence indicates protective effects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, fibrosis, and hepatotoxic injury.⁷ In one murine study of ethanol-induced hepatic injury, administration of A. muciniphila prevented and ameliorated steatosis. Additionally, supplementation in aged mice has been associated with reduced hippocampal IL-6 and improved cognitive performance, paralleling the effects of metformin.⁸

Mental Health

A. muciniphila levels were found to be lower in patients with depressive conditions, including bipolar disorder. In one cohort comparing severe versus mild depression, A. muciniphila abundance was negatively correlated with disease severity—the lower the levels in the gut microbiome, the more severe the depression. The proposed mechanism is that A. muciniphila binds to Toll-like receptors and increases intestinal serotonin. Although these findings are based on small sample sizes (fewer than 40 individuals), supplementation may be worth considering in patients with depression.

Potential Harms

Excess Enrichment and Barrier Dysfunction

Although beneficial in moderation, excessive A. muciniphila colonization may degrade the mucus barrier, leading to increased gut permeability and impaired tight-junction integrity.⁹ In low-fiber diets, high levels of A. muciniphila worsened food allergies in animal models, suggesting possible context-dependent harm.¹⁰

Disease-Specific Risks

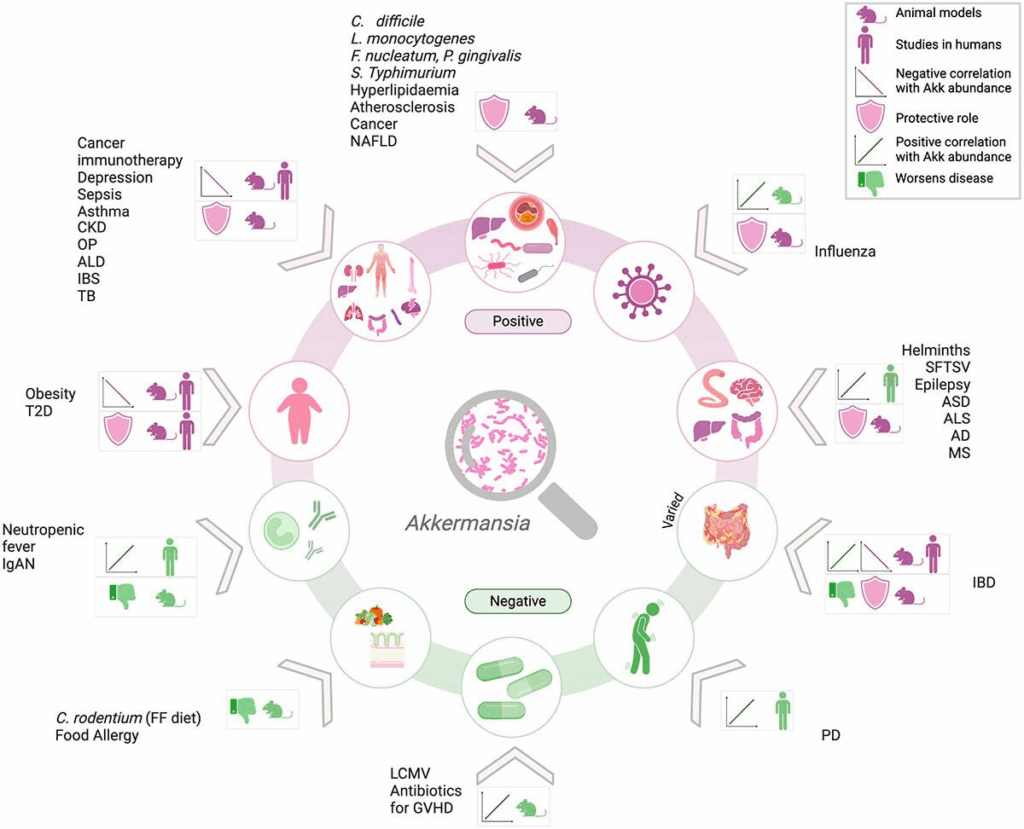

Supplementation may not be appropriate for individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, Salmonella infection, or during gut recolonization after antibiotic use.¹¹ One murine study of IBD raised concerns about colitis. Individuals with endometriosis are at elevated risk of developing IBD compared to others, so caution should be exercised when treating these patients with A. muciniphila.¹ Elevated A. muciniphila abundance has also been linked to neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, though causal relationships remain unclear.¹² Figure 1 provides a spectrum of health conditions and a graphical summary of multiple studies reviewed in one recent paper.¹⁴

Dietary Considerations

Multiple studies have shown that high-fat diets and alcohol consumption can lower A. muciniphila levels in the gut microbiome. A high-fat diet (60% fat) for as little as 8 weeks in mice led to a 100-fold decrease in A. muciniphila. Acute alcohol administration caused a similar 100-fold decrease in fecal bacterial abundance, accompanied by increased inflammation and oxidative stress.

Safety Evidence

The primary human trial demonstrated good tolerability without adverse events,⁴ but larger and longer-term studies are lacking. Additionally, the authenticity and viability of commercial A. muciniphila supplements remain a concern.¹³

Conclusion

Akkermansia muciniphila demonstrates significant potential as a next-generation probiotic, particularly for metabolic, inflammatory, and mental health–related conditions. Multiple studies show that A. muciniphila improves body weight, plasma biochemical and inflammatory markers, and the morphology of vital tissues. Administration of both live and pasteurized A. muciniphila significantly promotes gut, adipose, and liver health by modulating immune responses and lipid metabolism, as well as maintaining intestinal homeostasis by improving gut barrier function and microbiota composition. Given the superior health effects observed with pasteurized A. muciniphila, the pasteurized form appears to be a valid, safe, and potentially more cost-effective option to improve health and reduce the risk of metabolic disorders.¹⁷ Current human data are promising but limited in scope and duration. Short-term studies indicate supplementation is generally safe, though possible risks—particularly for individuals with specific illnesses or microbiome imbalances—should be carefully considered.

Dr. Sara Love is an ND 2010 graduate of the National University of Natural Medicine. She is a former member of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Advisory Commission and a current member of the Health Evidence Review Commission Value-based Benefits Subcommittee. Her current clinical practice is based in Beaverton, OR. When she is not seeing patients, she can be found on the local Oregon trails enjoying all the wildflowers, waterfalls, and wildlife.

References

- Chiantera V, Laganà AS, Basciani S, Nordio M, Bizzarri M. A Critical Perspective on the Supplementation of Akkermansia muciniphila: Benefits and Harms. Life (Basel). 2023 May 24;13(6):1247. doi: 10.3390/life13061247. PMID: 37374030; PMCID: PMC10301191.

- Chelakkot C, Choi Y, Kim DK, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles influence gut permeability through the regulation of tight junctions. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(2):e450. doi:10.1038/emm.2017.282

- Tabatabaei SAS,Ghadim HY, Sara Alaei,Abdolvand F, Mazaheri H;, et al. The association between the health of the intestines and the human body with Akkermansia muciniphila, The Microbe,2025; 7,100352 ISSN 2950-1946,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microb.2025.100352.

- Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):107-113. doi:10.1038/nm.4236

- Dao MC, Everard A, Aron-Wisnewsky J, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut. 2016;65(3):426-436. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308778

- Depommier C, Everard A, Druart C, et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat Med. 2019;25(7):1096-1103. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0495-2

- Zhang T, Li Q, Cheng L, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila is a promising probiotic. Microorganisms. 2021;9(10):1765. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9101765

- Ottman N, Reunanen J, Meijerink M, et al. Pili-like proteins of Akkermansia muciniphila modulate host immune responses and gut barrier function. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173004

- Grander C, Adolph TE, Wieser V, et al. Recovery of ethanol-induced Akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 2018;67(5):891-901. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313432

- Wang J, Xu W, Kong L, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila protects cognitive function and neuroinflammation in aged mice. Microbiome. 2023;11(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40168-023-01567-1

- Ganesh BP, Klopfleisch R, Loh G, Blaut M. Commensal Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates gut inflammation in Salmonella Typhimurium-infected gnotobiotic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74963. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074963

- Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Y. Regulation of food allergy by intestinal bacteria: mechanisms and clinical applications. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12(1):9-17. doi:10.4168/aair.2020.12.1.9

- Derrien M, Belzer C, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb Pathog. 2017;106:171-181. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.005

- Cekanaviciute E, Yoo BB, Runia TF, et al. Gut bacteria from multiple sclerosis patients modulate human T cells and exacerbate symptoms in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(40):10713-10718. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711235114

- van der Lugt B, van Beek AA, Aalvink S, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in humans: challenges and opportunities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(9):e02231-21. doi:10.1128/aem.02231-21

- Panzetta, M. E., & Valdivia, R. H. (2024). Akkermansia in the gastrointestinal tract as a modifier of human health. Gut Microbes, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2024.2406379

- Zhou K. Strategies to promote abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, an emerging probiotics in the gut, evidence from dietary intervention studies. J Funct Foods. 2017 Jun;33:194-201. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.03.045. Epub 2017 Mar 29. PMID: 30416539; PMCID: PMC6223323.

- Ashrafian, F., Keshavarz Azizi Raftar, S., Shahryari, A. et al. Comparative effects of alive and pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila on normal diet-fed mice. Sci Rep 11, 17898 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95738-5