Darin Ingels, ND

According to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, allergies affect more than 50 million people in the United States, and are the fifth-leading cause of chronic disease in all persons, and the third-leading cause of chronic disease in children under the age of 18.1 Allergic rhinitis affects up to 30% of adults and 40% of children worldwide, and the prevalence has increased each year over the past decade.2 The associated costs of treating allergic rhinitis in the United States are $11 billion, with expected increases in costs annually. Naturopathic physicians are well trained at helping to control and potentially eliminate allergies.

What Are Allergies?

The term “allergy” was created to describe an abnormal response to substances that your system recognizes as foreign, but which do not cause reactions in most people. These hypersensitivities to exogenous and endogenous substances can trigger both immune and non-immune reactions. Allergens include pollens (trees, grasses and weeds), animal danders, mold, dust and dust mites, foods, chemicals, drugs, air pollution, and perfumes. Allergies can produce symptoms in almost every organ of the body and often masquerade as other diseases. They can affect the skin, eyes, ears, nose, throat, lungs, stomach, bladder, vagina, muscles, joints, and the entire nervous system, including the brain. Allergic rhinitis is a global problem and is defined as the presence of at least 1 of the following: congestion, rhinorrhea, sneezing, nasal itching, or nasal obstruction.

Types of Allergic Reactions

The primary function of the immune system is to protect the host from foreign antigens. With allergies, the immune system abnormally reacts to antigens due to loss of immune tolerance, and the ensuing immune responses can lead to tissue injury and disease. The different components of the immune system interact in 4 distinct ways to produce an allergic reaction.

Type I Reactions (Immediate Hypersensitivity)

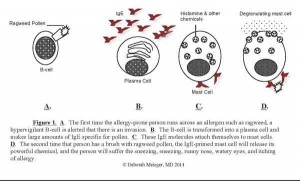

In this type of reaction, B-cells of an allergic person start producing specific IgE antibodies to an allergen, which then attach to mast cells and basophils throughout the body. The allergen binds to IgE antibodies on the surface of mast cells or basophils, resulting in the release of large amounts of histamine, which produces the subsequent allergic symptoms. Examples of this type of reaction include anaphylactic shock, allergic rhinitis, allergic asthma, and many acute skin reactions, such as acute drug reactions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immediate-Hypersensitivity Allergic Responses

- The first time the allergy-prone person runs across an allergen such as ragweed, a hypervigilant B-cell is alerted that there is an invasion

- The B-cell is transformed into a plasma cell and makes large amounts of IgE specific for pollen

- These IgE molecules attach themselves to mast cells

- The second time that person has a brush with ragweed pollen, the IgE-primed mast cell will release its powerful chemical, and the person will suffer the sneezing, runny nose, watery eyes, and itching of allergy

Type II Reactions (Cytotoxic Reactions)

These reactions involve the binding of either IgG or IgM antibody to a cell-bound antigen. Binding of the antibody results in activation of the complement cascade and the destruction of the cell to which the cell is bound. Some examples include autoimmune processes such as immune hemolytic anemia, Rh-induced hemolytic disease of a newborn, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, myasthenia gravis, and Graves’ disease (thyrotoxicosis).

Type III Reactions (Immune Complex-mediated Reactions)

Immune complexes are formed when antibodies bind to antigens (protein markers on molecules). They are usually cleared from the circulation by the phagocytes (macrophages). However, when an antigen and an antibody combine in large enough amounts, these complexes may be deposited in tissues and blood vessels. Their presence can lead to complement activation, chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, phagocytosis, and tissue injury. These processes are apparent in some types of nephritis, arthritis, drug reactions, and some infections, as well as in most autoimmune reactions.

Type IV Reactions (Cell-mediated or Delayed Hypersensitivity)

This type of allergic reaction is not mediated by antibodies, but rather by T-lymphocytes. In an allergic person, they are responsible for contact dermatitis, poison ivy reactions, and chronic granulomas. Delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions usually present as allergic symptoms, but generally require about 24 hours to develop following exposure to an allergen. Other allergic reactions in a previously sensitized individual can occur within minutes to hours; however, Type IV reactions can manifest in hours to days.

Causes of Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis can be precipitated by many environmental factors and is likely the cumulative effect of multiple exposures to various antigens. It is important that patients get appropriately tested to identify what the offending allergen(s) may be. There are many ways to do allergy testing to identify possible allergens. Blood testing for IgE antibodies to specific allergens (eg, radioallergosorbent test, or RAST), skin-scratch and skin-prick testing (done mostly for environmental allergens) are the common accepted methodologies for allergy testing. However, these methods specifically examine IgE reactions, thus do not reflect non-IgE-mediated allergic reactions.

Blood tests for IgG antibodies or other unorthodox testing methods, such as kinesiology, Carroll testing, or electrodermal screening, may be useful in identifying reactions not involving IgE. It is well established that genetics play a significant role in the development of atopy and allergic rhinitis. Environmental factors are also significantly involved in the development of allergies. Air pollutants, industrial chemicals, pesticides and herbicides, solvents, local environmental allergens (eg, pollen, mold, dust mites, and animal danders) and infections can all influence one’s ability to develop atopic symptoms. The duration, route of exposure, amount of exposure, and type of allergen dictate the degree to which the allergen affects an individual. In environmental medicine, we often use the concept of a barrel. Some people are born with a big barrel, and some with a smaller barrel. When the barrel overflows, the patient becomes symptomatic. Our goal as naturopathic physicians is to reduce the load in the barrel so that it doesn’t overflow.

Naturopathic Treatments for Allergic Rhinitis

Successful treatment of allergic rhinitis is multifactorial and should therefore encompass avoiding allergens when possible, controlling allergic reactions, managing inflammation, and potentially using desensitization therapy to induce a permanent change in the allergic response.

Allergen Avoidance

Whenever possible, it is best to advise patients to avoid an offending allergen. While this may be practical for foods, animal danders, or pollutants, it is not possible for microscopic allergens such as pollen or mold spores. When avoidance is not possible, it is recommended to institute some level of allergen control. For example, individuals who are allergic to dust or dust mites can use dust mite covers on their bedding to reduce dust mite exposure while they are sleeping, and also use a HEPA filter in their bedroom to help reduce circulating dust from the air. Using safe, non-toxic cleaning materials in the home is a simple way to help eliminate exposure to solvents, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and other chemicals that contribute to indoor air pollution. Patients with food sensitivities, allergies, or intolerances can avoid the offending foods while other treatments are used to reduce sensitivity to those foods.

Dietary Management

Environmental allergens are common triggers for allergic rhinitis, but studies have shown that food allergies can also manifest as allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis. Having your patients keep a complete diet diary may help gain insight into potential triggers. Instituting an elimination diet is also an inexpensive way to help identify food allergies or intolerances. As previously mentioned, more conventional methods can be utilized to identify food allergies, such as RAST or skin-scratch testing. In my own practice, I find food allergies to be a significant contributing factor to a patient’s allergic rhinitis, and the symptoms are drastically reduced when we eliminate the food triggers.

Managing the Gut

There has been a significant amount of research showing how important our gut microbiome is in the development of atopy. Two studies showed that probiotics improve digestion by limiting the absorption of food allergens and/or by changing immune responses to food.3,4 Another study found probiotics may also be important in non-allergic food intolerances.5 It is important to use strains that have been well researched to help maintain or reestablish a healthy microbiome, particularly for someone who has been on antibiotic therapy or chemotherapy (and thus may have altered gut flora).

In naturopathic medicine, we often discuss intestinal permeability (aka leaky gut syndrome) as a cause of allergy, but there is little clinical research that confirms this. At least 1 study found children with birch tree pollen allergy, who had undergone immunotherapy treatment, had no changes in their intestinal permeability compared with controls, before or during their treatment.6 It is unclear whether intestinal permeability is a contributing factor in the development of allergic rhinitis. More research is needed to clarify this issue.

Managing Symptoms of Rhinitis

Inhaled cromolyn sodium solution is effective at reducing symptoms of allergic rhinitis.7,8,9 Cromolyn sodium is a semi-synthetic bioflavonoid that acts as a mast cell stabilizer, thus inhibits the degranulation of mast cells. Patients administer 1-2 sprays up each nostril 2-3 times a day as a preventive measure to block mast cell degranulation. Cromolyn sodium has an excellent safety profile and no known drug interactions. It is often found over the counter at most pharmacies.

Vitamin E is also useful in the treatment of allergic rhinitis, as it is a mild leukotriene inhibitor.10 One study found that 112 adults with allergic rhinitis had significant improvement in nasal symptoms after taking 800 IU per day of vitamin E for 10 weeks.11 A diet high in vitamin E has also been shown to help prevent the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, with the protective effect of the vitamin increasing as the dose increased.12 I recommend using mixed tocopherols rather than alpha-tocopherol alone, as other studies have shown additional health benefits from using mixed tocopherols.

Research shows that consuming a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids, specifically eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), helps reduce the risk of developing hay fever in adults.12 Another study showed that children (aged 6 months to 3 years) given 184 mg of fish oil per day in addition to dust mite control, had a 10% reduction in cough and a 7.2% decrease in dust mite sensitization.13 Mothers who consume omega-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and the early post-natal period may modulate the immune system and reduce the risk of allergy development in their offspring.14

An extract of French maritime pine bark (Pinus pinaster) has been shown to inhibit the release of histamine from mast cells and inhibit leukotriene production. One in-vitro study showed that Pycnogenol® was as effective as cromolyn sodium in blocking mast cell histamine release.15 Pycnogenol is rich in bioflavonoids, which accounts for its mast cell-stabilizing effects.

A preliminary study showed that freeze-dried capsules of nettles (Urtica dioica) reduced sneezing and itching in those with hay fever.16 The recommended dose is 600-900 mg TID. Nettles has an historical use in botanical medicine for treating cough, tuberculosis, and arthritis. In-vitro studies suggest it may also have anti-inflammatory effects and inhibit prostaglandins.17

In an open-label study, 580 patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis took 50-75 mg BID of a butterbur (Petasites hybridus) extract (containing 8 mg petasines per tablet) for 2 weeks. Compared to baseline, post-treatment symptoms of rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, itchy eyes and nose, red eyes, and skin irritation improved in 90% of the patients.18 Butterbur is also a mild leukotriene inhibitor and was found in 1 study to be as effective as 180 mg of fexofenadine.19 Because butterbur contains potentially hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA), it should be used with caution, or a PA-free extract could be used instead. Butterbur is in the ragweed family, so should also be used with caution in those allergic to ragweed.

Additional nutrients and herbs that may help control allergic rhinitis include vitamin C, quercetin, N-acetylcysteine, and others; however, human data demonstrating their efficacy is lacking. Nonetheless, these nutrients are generally regarded as safe, so may be worth using in patients who do not respond well to other treatments.

Sublingual Immunotherapy

I have been doing sublingual immunotherapy for 15 years in my practice, and find it to be the best therapy for inducing immune tolerance to a specific allergen. Although it is not widely used in the United States, it has been used throughout Europe for almost 50 years. Although subcutaneous injection immunotherapy (SCIT) has been the gold standard for allergy desensitization for almost 100 years, at least 34 published double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have shown that sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is equally or more effective than allergy shots in reducing allergy and asthma symptoms. The allergy extracts used in SLIT are identical to those used in injection immunotherapy, but rather than receiving a shot on a weekly or monthly basis, oral drops are administered under the tongue, often on a daily basis. Allergic reactions to dust mites, molds, pollens, and foods can all be treated with SLIT.

A recent review of 5 meta-analyses, involving adults and children with allergies to house dust mite, grass pollen, or other various allergens, showed a 32-95% improvement in symptoms of allergic rhinitis and a 33-76% reduction in the use of allergy medications such as oral antihistamines. The magnitude of efficacy of SLIT therapy was found to be higher in those with more severe symptoms during grass pollen season: compared to placebo, the symptom-medication scores for low-, moderate-, and high-severity groups were 15%, 26% and 37%, respectively, among adults; and 10%, 33% and 34%, respectively, among children.20 No significant adverse effects were reported with SLIT.

There have been 4 studies comparing the effects of SLIT and SCIT. In 1 small study, 36 adults with house dust mite-induced asthma were assigned to receive SLIT, SCIT, or placebo SLIT for 1 year.21 After 1 year of treatment, those receiving SCIT had a significant reduction in asthma and rhinitis symptoms scores, whereas the group receiving SLIT had improvements in rhinitis symptoms scores only, compared with those taking placebo SLIT. Two of the studies demonstrated significant improvements in allergic rhinitis and asthma symptoms scores with both SCIT and SLIT, with no statistical significant difference between treatment groups compared with placebo.21 One open 2-year study using low-dose SLIT for Alternaria allergy found that allergic rhinitis scores were better in the SLIT treatment group than the SCIT group.21

I and other physicians have successfully treated thousands of patients with allergies and asthma with SLIT, and have not observed any significant side effects or severe reactions to the treatment. Although injection immunotherapy can take a year or longer to begin controlling allergies or asthma, SLIT will often diminish symptoms within weeks. Like any treatment, not everyone responds to SLIT, and some patients do feel better with allergy injections. Nonetheless, SLIT is a safe, effective treatment that should be considered as a first-line therapy in the treatment of allergies and asthma.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr Ingels is not affiliated in any way with the manufacturers of Pycnogenol®.

Darin Ingels, ND, is a respected leader in natural medicine, with numerous publications, international lectures, and more than 20 years of experience in the healthcare field. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in medical technology from Purdue University and his Doctorate of Naturopathic Medicine from Bastyr University in Seattle, Washington. Dr Ingels completed a residency program at the Bastyr Center for Natural Health. He is currently licensed in the States of Connecticut and California, where he maintains practices in both states. Dr Ingels is a member of the AANP, PedANP, CNPA, NYANP, CNDA, AAEM, and ACAM. His practice focuses on environmental medicine with special emphasis on chronic immune dysfunction, including allergies, asthma, recurrent infections, and other genetic or acquired immune problems. He uses diet, nutrients, herbs, homeopathy, and immunotherapy to help his patients achieve better health.

Darin Ingels, ND, is a respected leader in natural medicine, with numerous publications, international lectures, and more than 20 years of experience in the healthcare field. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in medical technology from Purdue University and his Doctorate of Naturopathic Medicine from Bastyr University in Seattle, Washington. Dr Ingels completed a residency program at the Bastyr Center for Natural Health. He is currently licensed in the States of Connecticut and California, where he maintains practices in both states. Dr Ingels is a member of the AANP, PedANP, CNPA, NYANP, CNDA, AAEM, and ACAM. His practice focuses on environmental medicine with special emphasis on chronic immune dysfunction, including allergies, asthma, recurrent infections, and other genetic or acquired immune problems. He uses diet, nutrients, herbs, homeopathy, and immunotherapy to help his patients achieve better health.

References:

- Allergy Facts and Figures. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. AAFA Web site. http://www.aafa.org/display.cfm?id=9&sub=30. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Allergy Statistics. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. AAAAI Web site. http://www.aaaai.org/about-the-aaaai/newsroom/allergy-statistics.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Kirjavainen PV, Gibson GR. Healthy gut microflora and allergy: factors influencing development of the microflora. Ann Med. 1999;31(4):288-292.

- Salminen S, Isolauri E, Salminen E. Clinical uses of probiotics for stabilizing the gut mucosal barrier:successful strains and future challenges. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70(2-4):347-358.

- Hunter JO. Food allergy-or enterometabolic disorder? Lancet. 1991;338(8765):495-496.

- Moller C, Magnusson KE, Sundqvist T, et al. Intestinal permeability as assessed with polyethyleneglycols in birch pollen allergic children undergoing oral immunotherapy. Allergy. 1986;41(4):280-285.

- Ratner PH, Erlich PM, Fineman SM, et al. Use of intranasal cromolyn sodium for allergic rhinitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(4):350-354.

- Meltzer EO, NasalCrom Study Group. Efficacy and patient satisfaction with cromolyn sodium nasal solution in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2002;24(6):942-952.

- Seo SB, Park SJ, Park ST, et al. Disodium cromoglycate inhibits production of immunoglobulin E. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2001;23(2):229-237.

- Centanni S, Santus P, Di Marco F, et al. The potential role of tocopherol in asthma and allergies: modification of the leukotriene pathway. BioDrugs. 2001;15(2):81-86.

- Shahar E, Hassoun G, Pollack S. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on the regular treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92(6):654-658.

- Nagel G, Nieters A, Becker N, Linseisen J. The influence of the dietary intake of fatty acids and antioxidants on hay fever in adults. Allergy. 2003;58(12):1277-1284.

- Peat JK, Mihrshahi S, Kemp AS, et al. Three-year outcomes of dietary fatty acid modification and house dust mite reduction in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):807-813.

- Prescott SL, Calder PC. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and allergic disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(2):123-129.

- Sharma SC, Sharma S, Gulati OP. Pycnogenol inhibits the release of histamine from mast cells. Phytother Res. 2003;17(1):66-69.

- Mittman P. Randomized, double-blind study of freeze-dried Urtica dioica in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Planta Med. 1990;56(1):44-47.

- Roschek B Jr, Fink RC, McMichael M, Alberte RS. Nettle extract (Urtica dioica) affects key receptors and enzymes associated with allergic rhinitis. Phytother Res. 2009;23(7):920-926.

- Kaufeler R, Polasek W, Brattstrom A, Koetter U. Efficacy and safety of butterbur herbal extract Ze339 in seasonal allergic rhinitis: postmarketing surveillance study. Adv Ther. 2006;23(2):373-384.

- Schapowal A; Study Group. Treating intermittent allergic rhinitis: a prospective, randomized, placebo and antihistamine-controlled study of Butterbur extract Ze339. Phytother Res. 2005;19(6):530-537.

- Incorvaia C, Masieri S, Scurati S, et al. The current role of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in adults and children. J Asthma Allergy. 2011;4:13-17.

- Cox L. Sublingual immunotherapy, part 1: Review of clinical efficacy. J Respir Dis. 2007;28(4):162-168.