Chlorosis or Poverty of the Blood

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

The chlorosis of young girls has become a fashion. There is scarcely one family with grown up daughters of which not one, at least, is suffering of chlorosis.

Benedict Lust, (1908, p. 6)

Nervousness and chlorosis or anaemia, often go hand in hand. The first thing to do is to remove the cause, which, in many cases, is tight lacing, the wearing of stays [corsets], want of nutritious food, too little exercise out of doors, general weakening and softening of the system.

Sebastian Kneipp, (1902, p. 185)

Do not wear corsets. … We may fool ourselves and part of the public but never the organs that suffer for the proper amount of space, because we have not the courage to live a natural life.

E. K. Stretch, (1916, pp. 101-102)

You have come a long way baby!

The phrase, ‘you have come a long way baby’, slammed through the cigarette advertising world some years back, pointing out the supposed huge strides in the equity of women, of course neglecting to include new data about the inevitable and accompanying surge in female lung cancer. Pernicious in a similar way was the dangerous manipulation of women’s fashion and clothing styles to the detriment of their health. The archaic condition “chlorosis” was an unnecessary condition arising from those fads. A century ago, a woman’s clothing, her work opportunities, and her living conditions collectively generated powerful impacts on her health. A prevailing lack of understanding of women’s actual medical needs grew from the paucity of information and research not only about the inappropriateness of, say, the use of corsets or the presenting condition of chlorosis, but also about women’s health overall. Living in this medical vacuum, women suffered. The conspicuous absence of women doctors administering to women at the turn of the last century compounded the serious misinformation and dearth of data.

In this environment, one popular and trivializing diagnosis projected frequently onto women was characterized by terms such as “hysteria” and “nerves” which fell under the umbrella of neurasthenia. Another common female diagnosis, referenced above, was the green sickness or chlorosis, “the twin sister of anemia” (Bilz, p. 1540)

Chlorosis was widespread among young women, affecting the delicate and not sparing the strong. In the first decade of the last century, Dr Seibert found that chlorosis affected those in “the higher strata of society” and remarked that “servant girls, as a rule, remain immune from it, while seamstresses, milliners, girls who work in factories, mostly those who have to live in poorly ventilated rooms and by their work are obliged to remain in an unnatural position, suffer from this sickness.” (Seibert, 1908, p. 79) Authors such as Kuhne and Lust also noted that chlorosis affected all classes of women. “Neither poor or rich, neither young or old, are free from these disorders.” (Kuhne, 1918, p. 352)

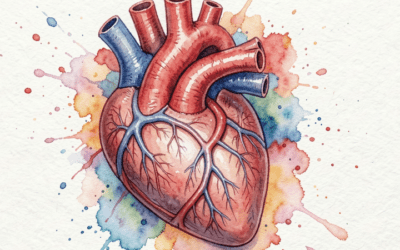

The symptoms of chlorosis experienced by young women resemble those of anemia. “The first symptoms of chlorosis are the pale, almost waxen color of the gums and the inner eyelids; languid physiognomy, heavy walk, palpitations of the heart, somnolence, sense of discomfort and disinclination for work.” (Lust, 1908, p. 6) The weakness felt in these young women may also be accompanied with “palpitations of the heart with the least exertion, a feeling of oppression, lethargy, and aversion to a meat diet.” (Bilz, 1898, p. 514) As Kuhne explained it, chlorosis “render[s] people mentally and physically unfit … with a loss of appetite and the bowels no longer act regularly.” (Kuhne, 1918, p. 352)

The quality of blood was paramount in understanding the full picture of chlorosis. Those with chlorosis illustrated clearly “the effects of poverty of blood”. (Kneipp, 1891, p. 234) Chlorosis impacted menstruation resulting in dysmenorrhea, or amenorrhea and “the bleeding … are most irregular, or leucorrhea appears, which greatly weakens the patient.” (Lust, 1908, p. 6) The blood flow could be scanty or profuse and of a pale red color. (Lust, 1920, p. 233) Menstrual cramps caused by “sedentary occupation or the corset contribute to the prevention of the right blood circulation” or blood stagnation. (Seibert, 1908, p. 80) Others, such as Kuhne saw irregularity and disturbances in menstruation as “an unmistakable proof of the presence of an encumbrance of morbid matter.” (Kuhne, 1918, p. 636)

Lust further explained, “Often chlorosis is accompanied with convulsive attacks.” (Lust, 1908, p. 6) Kuhne saw patients with chlorosis also experiencing epileptic fits. “Imperfect digestion in conjunction with insufficient activity of the skin and lungs were the sole causes of these diseases.” (Kuhne, 1918, p. 355) By treating the chlorosis, the fits were also cured. The causes of chlorosis were multifold but one huge factor was the impulse to achieve a notorious hourglass figure and then have to endure the consequences of the methods.

The Corset: Why were they worn? To improve the figure!

Trim tiny waists are as coveted by women today, as a century ago. The moment we see and feel the love handles growing on our bodies, we will stoop to starving, counting calories, HCG diets, exercise or anything to return our tiny waists. A century ago, the corset was quite effective in achieving this goal. “There has never been invented an instrument to a sure, though slow destruction of the body as the corset.” (Wagner, 1909, p. 13) The corset was designed to create an hourglass figure, but in doing so also “press[ed] the vital organs out of place, disfiguring the body, prevent[ing] breathing, caus[ing] stomach troubles, cancers or tumors of the breast, defective circulation, ill health and maternal injury.” (Neff, 1910, p. 149) “No wonder women have spasms, nervous prostrations, fits,” professed Dr Neff in his urge to women to discard the corset. “The natural form of the body cannot be improved upon by this health destroying corset, that disfigures the body until its natural shape is lost.” (Neff, 1910, p. 149) Women wearing the corset would find themselves “as if they should fall to pieces if the corset was removed.” (Gleason, p. 156) Like chlorosis and neurasthenia of the day, women’s use of the corset provoked much discussion in the naturopathic profession.

Dr Gleason was a female family physician in the 19th century who was disgusted with corset use claiming that: “tight clothing seems to squeeze out all common sense”. (Gleason, 1869, p. 157) She reasoned, “if the bottom of the waist is snugly bound, the diaphragm is limited in its action, hence the lower portion of the lungs are not fully inflated. The stomach and liver lack their proper play-room and needed motion, and with both digestion and respiration impeded, there is no power to keep health, in any part of the body.” (Gleason, 1869, p. 157) Berggren adds, that tight clothing and lacing “hindered the proper return of lymph and venous blood from the parts below the chest.” (Berggren, 1918, p. 344) It is no wonder that women in the late 19th and early 20th century would suffer with many ailments that soon characterized them as hysterical.

Not only did these women suffer wearing these ‘barbaric and inhuman forms of dress’, but their children also inherited ill health as well. “The pelvic congestion, as well as pressure on these organs, aids powerfully in predisposing to, if not, indeed, actually causing disease of these organs not only for the individuals themselves, but also for future generations.” (Berggren, 1918, p. 345) Lust noted that young women having children at a young age was detrimental to creating healthy children. In his view, if “government should prohibit marriage between too young people, we would have less distorted conditions, less nervous women and more healthy children.” (Lust, 1908, p. 6)

The treatment of chlorosis, in any case, followed sound nature cure principles, and most particularly, address the cause and the symptoms will take care of themselves. Recognizing that a sedentary lifestyle indoors contributed to chlorosis in young women, Lust prescribed “much exercise and no sedentary occupation [were] essential” (Lust, 1908, p. 6) to remedy chlorosis. Seibert also affirms Lust’s counsel, “all young girls, without any exception at all, from the princess down to the lowest girl of the people should assist a housekeeper in all that work done by servant girls.” (Seibert, 1908, p. 79). He continues, “Work, physical and intellectual culture of the most simple kind, is the best remedy against chlorosis and bodily and mental weakness.” (Seibert, 1908, p. 80)

Kneipp and his followers achieved great success treating patients with chlorosis who presented with pale skin and were thin and lacked vital heat. This was diagnosed as poor blood and “the first object then was to stimulate their appetite and circulation which [Kneipp] accomplished for the most part by partial washings or affusions.” (Bilz, 1898, p. 734) Kneipp recommended plenty of fresh air and to be “in the open air as much as possible and if they are in the room, this should be but sparingly heated.” (Kneipp, 1891, p. 234) We could certainly heed Kneipp’s advice as our current generation frets about Vitamin D deficiencies while spending increasingly more time indoors engaged in sedentary work.

The Kneipp cure for chlorosis of a strong constitution consisted of cold sitz baths which corrected “weak digestion and regulate the circulation of the blood.” (Kneipp, p. 48) The duration of the cold sitz bath was one to two minutes and the best time to be taken was at night which helped sleep. For those who were very weak and had very little vital heat, “the water applications should be gentle at first; in some cases, where cold feet are one of the symptoms, warm foot baths with salt and wood ashes.” (Bilz, 1898, p. 754) Kneipp recommended anemic women to walk “barefooted in the house and in the open air during summer and autumn.” (Kneipp, 1902, p. 186)

Another Kneipp treatment which was employed by Bilz at his sanitarium were the hot compresses. Bilz states,

the first thing is to produce perspiration. If that can be done, the patient is saved. A coarse cloth, folded several times, dipped in hot water and well wrung out, is laid as hot as possible on the stomach, and well covered up. In twenty minutes perspiration will generally take place. The cloth should then at once be again wrung out in hot water, and applied as before, in order to increase the perspiration. The whole body now perspires, the spasms cease and the patient feels better. (Bilz, 1898, p. 754)

Kneipp taught that “Good and sufficient blood is the first condition of health.” Healthy menses, in his view, did “not last longer than four or five days. … If the ‘flooding’ lasts over four days, a sitz bath must be taken on the fifth day of 79°F for ten minutes. During this time the body must be massaged or cooled by a douche.” (Wagner, 1909, p. 14) If the loss of blood was excessive, rather than cold sitz baths, “hot sitz baths of 96-104°F must be taken.” (Wagner, 1909, p. 14) For the treatment of dysmenorrhea, sitz bathing was recommended. “At first using water at about 80°F, gradually using cooler water until 60°F is found comfortable.” (Stretch, 1916, p. 101)

Fresh Vegetables

‘The regulars’ used chalybeate or iron in various forms, or quinine to treat chlorosis. The early naturopaths condemned the use of “artificial preparations for the purpose of ‘feeding up’ the patient “(Kuhne, 1899, p. 234) and advocated “a non-stimulating diet … [of] fresh vegetables, especially spinach and peas, rich in nutritive salts which strengthen bones and nerves, lettuce prepared with lemon instead of with vinegar.” (Wagner, 1909, p. 13) To build up the blood, Kneipp advised “powdered chalk or bone meal should be taken internally in water or vinegar and water twice a day, morning and evening. … Coffee, tea, beer and wine are as much to be eschewed as the wretched powdered iron which ruins the stomach and often also the teeth.” (Kneipp, 1902, p. 186) Kuhne, like many of his colleagues felt that chlorosis could “be cured only by expelling the foreign matter from the system, but never by medicaments”. (Kuhne, 1918, p. 356)

Dr Bilz’s sanitarium in Radebeul, Germany had a specific protocol for girls with chlorosis and anemia. The day began early in the morning with a barefooted walk in the fresh air, followed by the customary ablution [ranging 72°-84°F]. After this, breakfast was served consisting of crushed wheat. For those who did not eat this cereal breakfast, alternative options included a cup of cacao or sour milk. Lunch would include vegetables, some meat and fruit with a glass of wine taken a half hour before lunch. The afternoon snack consisted of cocoa or milk and the evening meal consisted of porridge, lettuce and fruit. (Wagner, 1909, pp. 13-14)

Today, anemia and its related lassitude, weakness and debility are replaced with obesity, rampant Vitamin D deficiencies and long hours sitting in front of computers or TV indoors. In too many ways so familiar to naturopathic doctors aware of the long traditions of nature cure and the conditions patients bring forward, we have not moved very far along the continuum of health and exhibit presenting conditions which are similar to those who came before us, albeit for new reasons.

Go out, take off your shoes and take a walk outside, just as Father Kneipp would have recommended.

References

Berggren, T (1918). Chest Expansion, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XXIII, #4, pp. 343-348.

Bilz, FE (1898). Bilz, The Natural Method of Healing, F E Bilz Publishing, Leipzig, Volume I, pp. 1-1056.

Bilz, FE (1898). Bilz, The Natural Method of Healing, F E Bilz Publishing, Leipzig, Volume II, pp. 1056-2011.

Gleason, RB (1869). Common Sense vs. Tight Dressing, The Herald of Health and Physical Culture, Miller, Wood and Co. Publishing, New York, Vol. 13, #4, pp. 156-158.

Hoegen, JA (1916). Hydrotherapy-Various Applications, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XXI, #7, pp. 468-469.

Kneipp, S (1891). My Water Cure, translated from the 62nd German Edition, Jos. Koesel Publisher, pp. 395.

Kneipp, S (1902). Diseases, Naturopath and the Herald of Health, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. III, #4, pp. 185-187.

Kuhne, L (1899). The New Science of Healing, Louis Kuhne Publishing, Leipsic, Germany, 460 pp.

Kuhne, L (1918). Poverty of the Blood, Chlorosis, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XVIII, #4, pp. 352 – 357.

Kuhne, L (1918). Diseases of Women, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XVIII, #7, pp. 635 – 641.

Lust, B (1908). Some Remarks about Chlorosis, The Naturopath and the Herald of Health, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. IX, #1, p. 6.

Lust, B (1920). Green Sickness or Chlorosis, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XXV, #5, p. 235.

Neff, JH (1910). The Corset, The Naturopath and the Herald of Health, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XV, #3, p. 149.

Seibert, E (1908). Prevention and Cure of Female Diseases by a Natural Method, The Naturopath and the Herald of Health, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. IX, #3, pp. 79-81.

Stretch, EK (1916). Gynecology: Minus the Knife, Herald of Health and the Naturopath, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. XXI, #2, pp. 101 – 102.

Wagner, O (1909). Lectures About Female Troubles, Held in the Kneipp Association in Bruenn, The Naturopath and the Herald of Health, Benedict Lust Publishing, New York, Vol. X,