Lynn Klassen, ND

Carolyn Mukai, ND

Rising temperatures and changing habitats are driving the spread of Lyme disease and co-infections into new regions—challenging outdated risk maps, diagnostic tools, and clinical assumptions.

Abstract

Climate change is expanding the habitat of ticks and their pathogens, fueling a surge of Lyme disease and co-infections in areas once considered low risk. This article examines how outdated surveillance maps and two-tier testing delay diagnoses, and it highlights integrative strategies—from flexible diagnostics to immune-modulating therapies—that help clinicians deliver timely, patient-centered care.

Introduction

As climate change continues to reshape ecosystems worldwide, its influence on infectious disease patterns has become impossible to ignore.1-6 Among the clearest examples is the northward and lateral expansion of tick-borne illnesses, particularly Lyme disease.1-3 ,6 Once regarded as confined to well-defined endemic regions, Lyme disease is now appearing in patients who live far beyond traditional endemic areas.1,2 This expansion challenges the assumptions built into surveillance systems and diagnostic frameworks, and it requires clinicians to adjust their approach to evaluation and care.3,4

Climate as a Driver of Change

Warming temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and shifting host reservoir populations have extended tick survival, synchrony, and habitat range.1,2,6,7 These changes are not hypothetical; they are measurable realities confirmed in ecological modeling and now reflected in patient presentations across North America.1,2,7 The mismatch between projected habitat expansion and the slower recognition of “new risk areas” is fueling diagnostic blind spots that harm patients and perpetuate underreporting. 3, 8

From Risk Maps to Real Patients

Surveillance systems often rely on case definitions that restrict reportable Lyme disease to patients with exposure in recognized “endemic” or “risk areas.” 3,4 Designed for public health tracking, this approach frequently fails real patients, who may present with classic symptoms but live in “low-risk” zones. 3,8,7 Cases from British Columbia demonstrate this vividly: individuals with clear exposures and compatible symptoms were not diagnosed or reported, because they lived outside a designated risk zone. The result is delayed treatment, misdiagnosis, and a growing population of patients with chronic, preventable illness.5,9

This dissonance reveals an uncomfortable truth: ecological change is moving faster than our reporting frameworks.1,2,6,7 Risk areas expand gradually on official maps, but in the clinic, tick bites and compatible symptoms present in real time.

Case Example from a Traditional “Low Risk” area

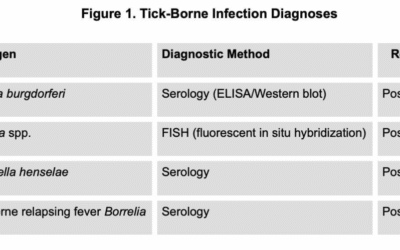

A 30-year-old female presented in our office ~6 months post “suspicious bite” while doing yard work in a traditional low-risk Lyme area of BC, Canada, with progressing neurologic dysfunction and arthritis. This patient had acute severe flu-like symptoms with headache within ~6 weeks of this suspicious bite, for which she was evaluated in the ER and initially diagnosed with a sinus infection. The patient was treated with a 7-day course of doxycycline followed by a 14-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate and subsequently tested for Lyme disease based on incomplete response to therapy, yielding a positive Borrelia burgdorferi serology. Follow-up testing ~3 weeks post antibiotic therapy was only positive on one tier of testing and interpreted as a false positive by her physicians, and discharged without further treatment recommendations or follow-up with infectious disease. This recommendation was given despite the fact that the patient had persisting symptoms consistent with Lyme disease and tick-borne illness and initial positive serology.

This patient’s integrative assessment at ~6 months post-acute illness included a thorough co-infection screen that yielded evidence for Babesia, Bartonella co-infection, and possible reactivation of EBV, which were likely complicating her presentation and progression.

Treatment consisted of restarting and combining different IV and oral antibiotic therapies in addition to herbal and nutrient-based antimicrobial and immune system support lasting 12 months before the patient reported significant and maintained improvement.

Immunomodulators like low-dose naltrexone, cromolyn, and ketotifen were very important in this patient’s ongoing management post-antibiotic therapy for infection-associated phenomena, including possible autoimmune phenomena, mast cell dysfunction, and dysautonomia.

Rethinking Clinical Lexicon and Practice

The language of “endemic” versus “low risk” areas, though useful in epidemiology, can bias clinical decision-making.3,6,7,8 When clinicians internalize these distinctions, they may dismiss plausible cases in nontraditional regions.10 This is compounded by the limitations of two-tier serologic testing, which often fails in early infection or with non-classical Borrelia strains.4,8,9 The net effect is a feedback loop: fewer diagnoses lead to fewer reported cases, reinforcing the false notion that risk is low in those areas.3,4,8

For clinicians, the takeaway is straightforward: clinical suspicion should not be limited by maps. Clinicians need to keep Lyme Disease and associated co-infections on their differential. Every suspicious bite deserves careful evaluation, and clinical presentation should take precedence over geographic assumptions.1,2, 5-7, 9

Integrative Response Strategies

As the climate continues to reshape infectious disease dynamics, integrative approaches to diagnosis and treatment become essential. These strategies include:

- Exposure-based risk assessment: Prioritize detailed occupational, recreational, and travel histories when evaluating unexplained systemic illness.

- Flexible diagnostic frameworks: Use serology as a tool, but not the sole determinant of diagnosis. Consider supportive testing (PCR, T-cell-based assays, expanded co-infection panels) where appropriate.

- Integrative treatment: Combine antimicrobial therapy with immune modulation, symptom management, and supportive care to address the multi-system impact of persistent infections and post-infection or infection-adjacent phenomenon.

- Patient-centered decision-making: Engage patients in transparent discussions about risks and benefits of different approaches, especially in contexts of diagnostic uncertainty.

Broader Implications

Lyme disease is a case study for a larger lesson: climate-driven changes are disrupting the patterns upon which our diagnostic reflexes and surveillance systems rely. The need for adaptive, climate-informed healthcare is urgent. Just as guidelines evolve to reflect new evidence, clinical reasoning must evolve to reflect a rapidly changing ecological reality. 1, 6-8

Conclusion

Tick-borne illness is no longer constrained to historical “endemic” zones. As climate change accelerates, clinicians must look beyond outdated maps and testing limitations, recognizing that exposure risk and clinical presentation should guide diagnosis and treatment. By shifting our frameworks and embracing integrative strategies, we can improve outcomes for patients while contributing to a more accurate understanding of infectious disease in a warming world.

Dr. Klassen, ND maintains a focused practice on Lyme disease and chronic illness. As a Lyme Literate ND (LLND), Dr. Klassen is trained in the latest developments in the testing and treatment of these difficult diseases. Dr. Klassen is the owner of Tandem Clinic in Vancouver’s Olympic Village, currently serving as the president of the BCND, and has developed Canada’s first and only CNME accredited naturopathic residency focused on Vector-borne illness and Chronic Complex Disease. “Like you, I’m frustrated by the lack of knowledge of tick borne illness in the medical system and the lack of understanding of the impact it’s having on people’s lives. I see patients every day that are overlooked by the medical system; no one should feel like they are not heard by their health care practitioner.”

Dr. Mukai, ND focuses her naturopathic practice on Lyme disease and associated infections and more broadly on complex chronic illnesses. She practices at Tandem Clinic in Vancouver, where she completed her 2-year residency in Vector-borne illness and Complex Chronic Disease. Dr. Mukai is passionate about collaborating with other health providers with the goal of increasing practitioner awareness of tick-borne illness. “My goal as a naturopathic physician is to provide comprehensive care for Lyme disease and associated illnesses while also raising awareness for these conditions as it relates to other chronic, complex, or unexplained illnesses. It is especially important to me to educate other practitioners to facilitate earlier detection and treatment for Lyme disease and associated infections to prevent progression to chronic illness.”

References

1. Ogden NH, Maarouf A, Barker IK, et al. Climate change and the potential for range expansion of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(1):63-70.

2. Leighton PA, Koffi JK, Pelcat Y, Lindsay LR, Ogden NH. Predicting the speed of tick invasion: an empirical model of range expansion for Ixodes scapularis in Canada. J Appl Ecol. 2012;49(2):457-464.

3. Canada PHA. Lyme disease: Monitoring – Canada.ca. Updated 2023.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance Data | Lyme Disease | CDC. Updated 2022.

5. Davidson A, Kelly PH, Davis J, Major M, Moïsi JC, Stark JH. Historical Summary of Tick and Animal Surveillance Studies for Lyme Disease in Canada, 1975-2023: A Scoping Review. Zoonoses Public Health. 2025;72(1):9-22. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/zph.13191

6. Wiskel, MD T, Al-Lawati, MD H, Humphrey, MBBS, MPH K. Climate Change Effects on Vector-Borne Disease: The Case of Lyme. Contagion. 2023;8(1).

7. Couret J, Schofield S, Narasimhan S. The environment, the tick, and the pathogen – It is an ensemble. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1049646. Published 2022 Nov 2. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.1049646

8. Altizer S, Ostfeld RS, Johnson PT, Kutz S, Harvell CD. Climate change and infectious diseases: from evidence to a predictive framework. Science. 2013;341(6145):514-519. doi:10.1126/science.1239401

9. Hirsch AG, Poulsen MN, Nordberg C, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of treatment delays in Lyme disease: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Front Med. 2020;7:560018.

10. Mader EM, Ganser C, Geiger A, et al. A Survey of Tick Surveillance and Control Practices in the United States. J Med Entomol. 2021;58(4):1503-1512. doi:10.1093/jme/tjaa094