STEPHEN W. PARCELL, ND

Too often, patients seeking age-management medicine tend to be most interested in their appearance. Because of this demand, medical professionals tend to also focus on cosmetic interventions, including testosterone for big muscles, hair implants, skin peels, laser treatments, dermabrasion, hormone replacement, and endless supplements – all toward the goal of hopefully looking better. I believe more emphasis should be placed on disease prevention. Though dermatologic improvements have obvious merit, prevention of serious diseases such as heart attack, stroke, and cancer often get sidelined because they hold less sex appeal. “Anti-aging medicine” will not do us any good if we die of a stroke or heart attack next week. Real optimal aging occurs from the inside out. While it will take no convincing of a naturopathic doctor that sleep, exercise, diet, and lifestyle factors promoting healthy adaptation to stress are the underpinnings of health and age management, this concept is often underemphasized by conventional anti-aging providers.

Vascular Health & Aging

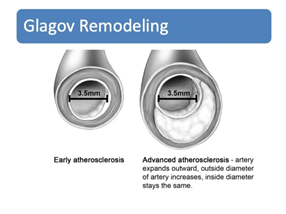

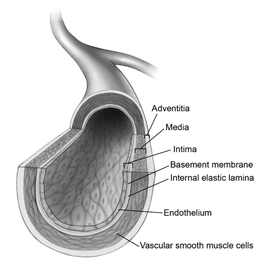

Longevity is mainly a vascular issue. In the United States, cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of morbidity and mortality.1 This thought is well represented by the axiom, “A man [person] is only as old as his arteries,” coined by the famous physician, William Osler, MD, in 1894. Though modifiable, artery thickness can be predicted as a population ages, despite aggressive treatment for established risk factors such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. This is because chronological age causes arterial thickening, endothelial dysfunction, vascular stiffening, and arterial remodeling (Figure 1).1 Morphological changes occur in all layers of the vasculature, but mainly involve intimal thickening. It is common for vascular smooth muscle cells to become less involved in contraction, and more involved in processes that thicken the artery wall.

Figure 1. Glagov Remodeling

Figure 2. Vessel Anatomy

Such morphological changes result in a stiffening of the vasculature. Vascular stiffness, in turn, causes increased systolic blood pressure (BP) and pulse pressure, and a decrease in diastolic BP. Pulse pressure is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressures. For example, if your systolic BP is measured as 120 mm Hg, and your diastolic BP is 80 mm Hg, then your pulse pressure would be 40 mm Hg. Optimal pulse pressure is between 40 and 60 mm Hg. Lower is better, as a high pulse pressure places increased mechanical stress on the vasculature.

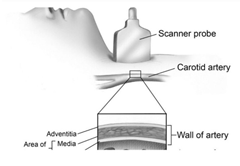

Atherosclerosis, though important, may be over-appreciated, while stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, thickening, and pathologic remodeling may be under-appreciated. There is an emerging concept that vascular age is a better predictor of cardiovascular events than chronological age.2 The ability to measure vascular age is now possible largely because of the existence of new, more accurate technologies for measurement. Examples include measurement of carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) using ultrasound and specialized software (Figure 3), pulse wave velocity testing, and a host of new serum biomarkers now available, such as a “novel coronary heart disease risk-assessment tool” (CHDRA), which is now available under a commercial name.3

Figure 3. Measurement of CIMT

Similar to skin, our arteries are subject to aging. The trajectory to dysfunction, however, can be modulated with diet, lifestyle, exercise, and specific targeted nutraceuticals.

Diet & Lifestyle Measures

There is wide range of degrees of seriousness and energy that one can put into the pillars of health. It is okay to say, “Follow a healthy diet,” but what does that mean? It can be on a scale of 1-10. An optimal plant-based diet includes a variety of fresh fruits, fungi, leafy greens and vegetables, proteins, and plant fats from legumes, seeds, beans, nuts, and whole grains. This is the best way to lower inflammation, oxidative stress, blood pressure, cholesterol, and cancer risk, and to improve skin health. The science supports this. Plant-based diets can be individualized to address conditions such as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, obesity, and gastrointestinal disorders. Many people think of a plant-based diet as inherently high in carbohydrates and low in protein. In actuality, a plant-based diet can be easily customized to be low or high in protein, carbs, and fat, depending on the specific needs of the individual.

Regular exercise reduces arterial pressure and heart rate, as well as the degree of strain with each cycle and the total number of cycles. Optimal blood pressure is still around 120/80 mm Hg or less. The key word here is “optimal.” The lower the BP, the better, as long as syncope, fatigue, and dizziness do not occur.

As a growing body of literature cites the dangers of a sedentary lifestyle and the benefits of physical activity, there is growing consensus that more exercise is better and that most of us don’t get enough exercise for optimal health.4 Mayo Clinic states, “As a general goal, aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity every day. If you want to lose weight, maintain weight loss or meet specific fitness goals, you may need to exercise more. Want to aim even higher? You can achieve more health benefits if you ramp up your exercise to 300 minutes or more a week.”5 An ideal exercise prescription might range between 30 minutes of walking per day and 90-120 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous exercise, at clinicians’ discretion. The body can handle much more than most of us realize, and the fitter you are, the less relative risk you have for most diseases. As primates, we simply were not designed to walk a little and spend the rest of the time sitting. Analysis of the intersection between cardiovascular mortality and hours of exercise demonstrate progressive reduction of risk with more exercise.4

Exercise is critical for longevity because it increases the endogenous antioxidant system, strengthens the heart muscle (which lowers heart attack risk), lowers cholesterol and triglycerides, and reduces blood pressure. It also lowers risk of dementia, improves mood, modulates cholesterol, optimizes glucose metabolism, and preserves skeletal muscle. In addition, flexibility decreases with age, which is why yoga and stretching are good anti-aging strategies.

Arterial Stiffening

Just like the skin, arteries contain elastin and collagen. Arteries such as the aorta have more elastic properties compared to distal components of the vasculature. The stiffness of an artery is related to how much collagen compared to elastin is in the vessel wall. As we age, proteins accumulate inside the artery wall, causing fragmentation of the elastin, and deposits of collagen multiply. The combination of these factors promotes arterial stiffness.6

Inflammation plays a part in vascular aging as well. Specifically, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other molecules encourage pathologic remodeling of the artery through chemoattractant and pro-oxidative forces.7 Furthermore, as local nitric oxide production decreases, endothelial cells lose their protective capacity. Footnote: Entire books have been written about the role of the endothelium; in short, the endothelium is the first line of defense, participating in all aspects of vascular homeostasis, and is responsible for processes such as thrombosis vascular remodeling, regulation of vascular tone, coagulation, and fibrinolysis, as well as blood vessel formation.8

Like epidermal cells, the vasculature is subject to cross-linking from advanced glycation end-products (AGEs).2 AGE-related cross-linking results from a non-enzymatic reaction between reducing sugars and proteins such as collagen. This cross-linking manifests as arterial stiffness and is a sensitive early measure of vascular health.2 It can be assessed noninvasively by measuring pulse wave velocity.2 If a patient has systolic hypertension and is over 40 years old, there is a good chance that his arteries are aging and getting stiffer.

Arterial stiffness is, in itself, a disease that propagates in a feed-forward cycle, leading to higher systolic blood pressure, end-organ damage from high pulsatile pressure, further endothelial dysfunction, and microvascular disease affecting the brain, eye, and kidney.9 Heart muscle is also affected. Arterial stiffening increases the afterload, which in turn increases the risk of pathologic remodeling. Possible outcomes include left ventricular hypertrophy, overcompensation, diastolic dysfunction, heart failure, and volume overload.10

While we will all experience arterial stiffening as we age, it is possible to slow down the process and even reverse it. Just like arterial plaque can regress, arterial stiffness can improve as well. Simple measures work, such as increasing nitric oxide delivery through exercise or L-arginine supplementation, and ingestion of nitrates found in leafy greens, especially arugula, cilantro, Swiss chard, basil, and spinach. Beets are less effective; however, beet juice is very effective.

All human systems depend on optimal blood flow for the delivery of oxygen and nutrients. As we attempt to increase the health span of our patients, many of us now suffer from conditions associated with vascular aging (eg, vascular dementia). This is because vascular aging is often an unseen, asymptomatic progression over many years. The remainder of this article will focus on some clinically relevant and easy-to-implement strategies to use with your patients.

Testing

It is very important to objectively measure vascular age. After all, why guess when you can know?

- CIMT testing. Use the same company for all repeat testing, so that you can accurately view changes over time. Verify that the lab technicians are trained adequately and that the best software is being utilized. Do not depend on conventional Doppler for this measurement.

- CHDRA tool

- Biomarkers through conventional reference laboratories, in addition to routine annual physical testing:

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), homocysteine, lipoprotein (a), oxidized LDL (oxLDL), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), lipid subfractions, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), myeloperoxidase, ferritin, MTHFR, 25-hydroxy-vitamin D, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). There are additional useful markers, but this is more than enough for non-specialists.

Treatment

General Goals

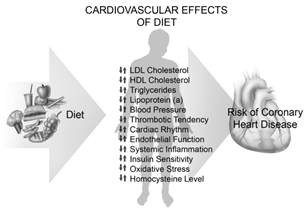

There are some general measures that help to enhance vascular longevity (Figure 4):

- Optimize cholesterol: This can be done through via a plant-based diet, exercise, the addition of super-foods, and supplements. Foods that improve cholesterol include, but are not limited to, almonds, cashews, Brazil nuts, avocados, ground flaxseed, soy, oats, whole grains, dietary fiber, and green tea.

- Lower inflammation: Implement a plant-based, anti-inflammatory diet. If the patient is unable to follow such a restrictive diet, add supplemental antioxidants, such as resveratrol, green tea, coenzyme Q10, curcumin, omega-3 fatty acids (EPA, DHA), lipoic acid, grape seed extract, astaxanthin, etc. Recheck inflammation markers to make sure your treatments are working.

- Enhance nitric oxide production: NO is critical for healthy endothelial function. NO addresses vascular homeostasis by acting as an antioxidant, modulating vascular tone, regulating cell proliferation, and protecting against toxic insult and mechanical/chemical damage. Dietary approaches to increasing nitric oxide production include the ingestion of leafy greens, especially arugula, kale, and spinach. Nuts contain arginine, which increases NO production. Sustained-release L-arginine is also effective. Unfortunately, there is no accurate test for measuring nitric oxide production in a patient; however, improvements in erectile dysfunction and/or blood pressure, as well as improved circulation, are indicators that your measures are effective. Also, consider running an asymmetric dimethylarginine test (ADMA). A positive test indicates the need for extra NO support. Exercise also greatly increases endogenous NO production.

- Optimize blood pressure (120/80 mm Hg or less, with pulse pressure below 50): Hypertension, regardless of causes, puts mechanical stress on the arteries, similar to constant stretching of the skin. Damage to the endothelium results, making it easy for cholesterol particles to get in and contribute to plaque formation. With more mechanical stress and more plaque, the arteries get stiffer; this in turn leads to higher blood pressure – a vicious cycle.

- Address toxic metals: Naturopathic doctors love environmental medicine, so should not overlook this. Lead and mercury are 2 of the big players here. Lead can cause high BP.11 Mercury has been demonstrated to increase oxidative stress within arteries. As mercury levels increase, there tends to be more atherosclerosis.12 Iron is critical to look at too, especially in men. Iron causes oxidative damage, especially to arteries.13 Serum ferritin, along with serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), should be performed. Ferritin may also be elevated as a result of liver disorders, so all 3 of these tests should ideally be done together.

- Ideally, run a provoked toxic metal test, preferably intravenously with calcium EDTA. Also administer IV DMPS or oral DMSA. A recommended DMSA dose is 30 mg/kg; DMPS dose is 3-5 mg/kg; and the standard calcium EDTA dose is 3 mg/kg. In my opinion, hair tests and blood tests for toxic metals are virtually useless. Extensive information exists within the naturopathic continuing-education courses on IV therapy.

Diet (Eliminate)

The following compounds should be completely eliminated from the diet:

- Advanced glycation end–products (AGEs): Created by the Maillard reaction, AGEs cause arterial aging. The pathologic effects of AGEs are related to their ability to promote oxidative stress and inflammation by binding with cell surface receptors or cross-linking with body proteins, altering their structure and function.14 Besides forming in the body, AGEs also exist in foods. AGEs are naturally present in uncooked animal-derived foods, such as cheese and meat. Cooking results in the formation of new AGEs within these same foods. In particular, grilling, broiling, roasting, and frying create new AGEs. Roasted nuts are high in AGEs, but not raw nuts. Bacon has the highest levels of AGEs ever measured.

- Heterocyclic amines (HCAs): HCAs are a major class of poisonous compounds produced during the broiling and frying of carnitine-containing foods such as meats. HCAs are genotoxic, which means they eventually foster mutagenicity and carcinogenicity, in addition to endothelial injury.14

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Ubiquitous in the environment, at least 90% of exposure to PAHs occurs through the diet. Meat-cooking methods such as roasting, grilling, barbecuing, and smoking generate PAHs.15 These compounds cause oxidative stress, increase BP, and promote endothelial injury.

- Trans fatty acids (TFAs): Both fully hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, and to a much lesser extent TFAs in animal fats, should never be consumed. TFAs increase triglycerides, reduce LDL particle size, reduce HDL, and increase LDL.16 Clinical studies have shown that TFAs also increase systemic inflammation and result in increased concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukin-6, and CRP.16 TFAs cause endothelial dysfunction too, as demonstrated by reduced brachial flow-mediated vasodilation of up to 30%.16 They also been shown to increase visceral fat and insulin resistance.16

- Foods that increase trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO): TMAO is a molecule generated from choline, betaine, and carnitine via gut microbial metabolism. TMAO is a byproduct of consuming egg, meat, fish (yes, fish), and milk. Researchers found that people with higher levels of TMAO may have more than twice the risk of heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular problems, compared with people who have normal levels.17 TMAO can cause damage to the kidneys, heart, liver, and blood vessels via different mechanisms.17 TMAO causes changes in cholesterol levels, activates inflammatory pathways and promotes foam cell formation, a critical step in atherosclerosis.17 One of the most scientifically probable links between consumption of animal foods and increased risk of heart disease is TMAO.18 In the case of fish, TMAO is already in the flesh. Also, eating these foods (especially red meat) ramps up the gut bacteria that elevate TMAO in the first place. Olive oil, fresh fruits and vegetables, fiber, grapeseed oil, garlic, red wine, grape juice, grapes, and resveratrol capsules all help lower TMAO. Plant-based diets may reduce TMAO within a few weeks.18

Figure 4. Cardiovascular Effects of Diet

Due to space limitations, a detailed discussion of dietary supplements and nutraceuticals is best left for another article. The typical nutraceuticals for vascular health are the ones that protect DNA, lower cholesterol, reduce blood sugar and the insulin response, lower BP, and are antioxidant. Some examples include green tea, resveratrol, NAD+, curcumin, L-arginine, magnesium, and pomegranate extract. There are also interesting data on metformin and angiotensin receptor blockers.

Summary

In summary, there are extensive diagnostic and treatment options for patients seeking advanced age management. Opportunities exist for expanding the scope of benefit to patients who come in seeking cosmetic enhancements. Significant improvements in arterial health are possible using simple measures such as diet and exercise. Skin appearance can improve from the inside out. Patient “buy in” is critical. To achieve patient compliance and precise treatment, objective testing is recommended. Showing patients their arterial age via CIMT measurement, their calculated cardiovascular age compared to biologic age, and the results of inflammatory markers and the novel CHD risk-assessment test, can be quite motivating.

References:

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528.

- Barodka VM, Joshi BL, Berkowitz DE, et al. Review article: implications of vascular aging. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(5):1048-1060.

- Solomon MD, Tirupsur A, Hytopoulos E, et al. Clinical utility of a novel coronary heart disease risk-assessment test to further classify intermediate-risk patients. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(10):621-627.

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):801-809.

- Laskowski ER. How much should the average adult exercise every day? April 27, 2019. Mayo Clinic Web site. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/expert-answers/exercise/faq-20057916. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. Elastin in large artery stiffness and hypertension. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5(3):264-273.

- Tuttolomondo A, Di Raimondo D, Pecoraro R, et al. Atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(28):4266-4288.

- Galley HF, Webster NR. Physiology of the endothelium. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(1):105-113.

- O’Rourke MF, Safar ME. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension. 2005;46(1):200-204.

- Zhang J, Chowienczyk PJ, Spector TD, Jiang B. Relation of arterial stiffness to left ventricular structure and function in healthy women. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2018;16(1):21.

- Zheutlin AR, Hu H, Weisskopf MG, et al. Low-Level Cumulative Lead and Resistant Hypertension: A Prospective Study of Men Participating in the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(21):e010014.

- Farkhondeh T, Afshari R, Mehrpour O, Samarghandian S. Mercury and Atherosclerosis: Cell Biology, Pathophysiology, and Epidemiological Studies. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01899-w. [Epub ahead of print]

- Gaenzer H, Marschang P, Sturm W, et al. Association between increased iron stores and impaired endothelial function in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(12):2189-2194.

- Weisburger JH. Lifestyle, health and disease prevention: the underlying mechanisms. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11 Suppl 2:S1-S7.

- Poursafa P, Moosazadeh M, Abedini E, et al. A Systematic Review on the Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Cardiometabolic Impairment. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:19.

- Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Trans fatty acids: effects on cardiometabolic health and implications for policy. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79(3-5):147-152.

- Janeiro MH, Ramírez MJ, Milagro FI, et al. Implication of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Disease: Potential Biomarker or New Therapeutic Target. Nutrients. 2018;10(10). pii: E1398. doi: 10.3390/nu10101398.

- Zhu Y, Li Q, Jiang H. Gut Microbiota in Atherosclerosis: Focus on Trimethylamine N-Oxide. APMIS. 2020 Feb 28. doi: 10.1111/apm.13038. [Epub ahead of print]

Stephen W. Parcell, ND, earned his doctorate in naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University in 2002. Dr Parcell worked as a freelance medical researcher at U of WA Medical School. He has done additional trainings through the ACAM, the National Lipid Association (NLA), AAEM, and the American Academy for Anti-aging Medicine (A4M). He is board-certified in anti-aging medicine through A4M. He is a past vice president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Doctors (COAND). Dr Parcell is a paid speaker and educator, has been a contributing writer, published peer-reviewed articles, and authored a book titled Dare to Live. He is co-owner of NatureMed Integrative Medicine, in Boulder, CO.