JACOB SCHOR, ND, FABNO

If I were to make a bucket list – and, admittedly, I do not usually think in such terms – I would very much like to spend a few hours walking through a New England hardwood forest where the ground is carpeted with ginseng plants, a classic bed of Panax quinquefolius. I want to see what it feels like. In my mind, these plants will collectively have a psychic presence that can be felt. As many times over the years that I have walked through a forest, I’ve never seen ginseng in the quantities that once existed, and I suspect that its absence leaves the forest lacking as if part of its soul has been abducted.

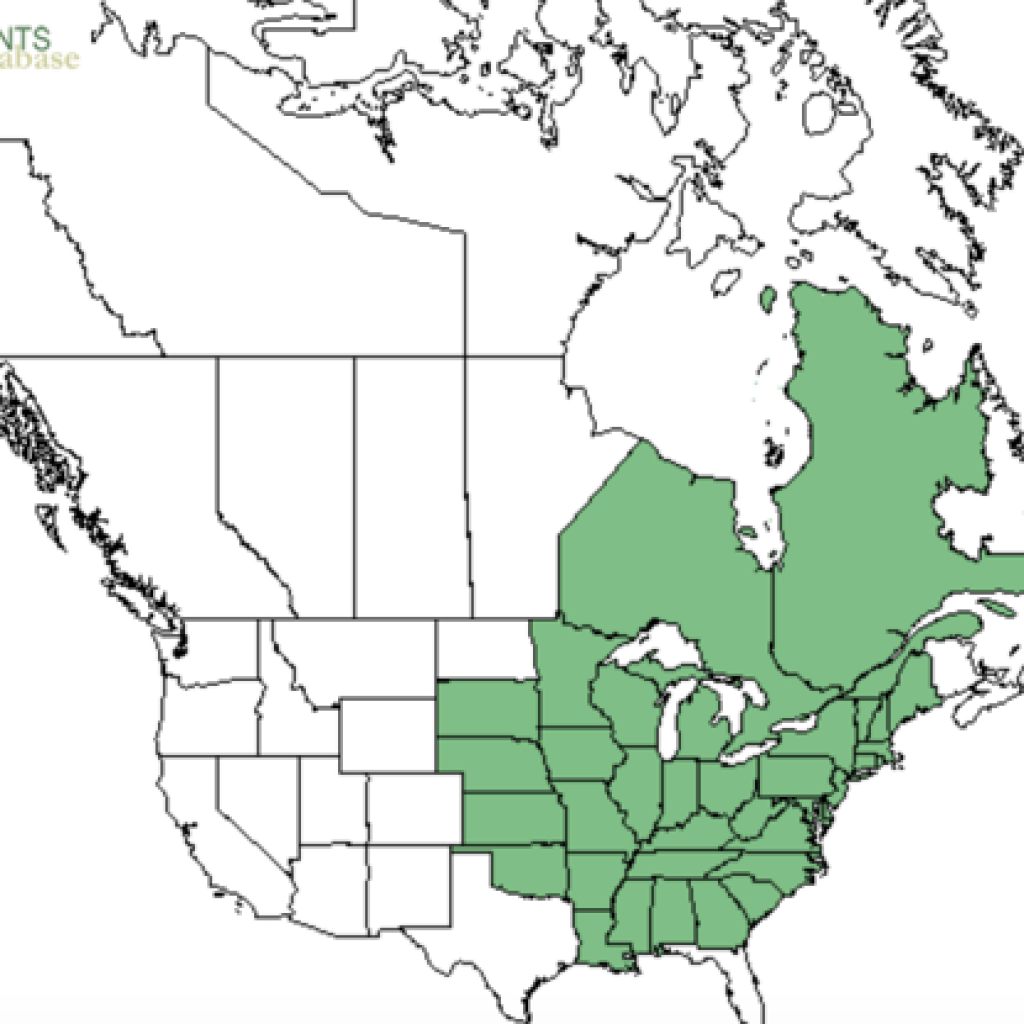

Ginseng’s native habitat once extended from Florida, north through the Appalachian Mountains, into Canada, and along the eastern shores of Hudson Bay and as far west as Kansas and Nebraska (Figure 1). The plant was nearly ubiquitous over the eastern half of our continent, but now it’s pretty much gone.

Figure 1. Distribution of American Ginseng1

Ginseng’s Life Cycle & Cultivation

Ginseng is a long-living and rather slow-growing herbaceous perennial valued for its taproot, which is similar enough to the Asian Panax ginseng to command an equally high price.

Seeds that have overwintered in the ground will typically sprout between April and June, producing 3 tiny leaflets on a single small stem. During its first season, the plant will look like a wild strawberry plant and stand about 2-5 inches tall. During the plant’s second season, it will grow to about 5 inches and will have 2 prongs branching from the central stem, each of which will have 3-5 leaflets. With good conditions, each year the number of prongs, each with 5 leaflets, will increase. In time and with good fortune, the plant will grow to over 2 feet tall. Each fall, when the foliage falls away, the stem will break off, leaving a scar at the top of the root. The bud that remains on the opposite side of this scar will produce a new stem the following year. This annual scarring reveals the age of the plant.

Plants that survive to 3 years flower in early summer. By mid-summer, these flowers, if fertilized, yield green berries that slowly ripen to a bright crimson color in the fall. Each berry will yield 1-3 seeds. Once the seeds fall from the plant, they take 18-20 months to germinate, assuming they are not eaten by rodents, deer, and turkeys or destroyed by disease.

Human interaction with this plant species has historically been a 1-way transaction driven by greed. For the past 3 centuries, harvesting wild ginseng has been a way for people to make easy money.

The history of this harvest is surprisingly well documented. On April 12, 1711, a Jesuit Missionary named Pierre Jartoux sent a letter to his Order Superior that described the many things he had seen and learned during his 20 years of service in China (or what he called Tartary). In the letter, he described Chinese Ginseng (Panax ginseng), a plant that for thousands of years had been highly valued for its medicinal properties. Jartoux suggested that growing and harvesting ginseng might be a profitable way for their organization to finance their global missionary aspirations. Jartoux’s letter was published as part of a compilation of letters in 1713,2 and copies were circulated among other Jesuits serving around the world.

In the fall of 1715, Jartoux’s ginseng description reached a Jesuit brother, Joseph-François Lafitau, who was serving at a mission to the Mohawk, one of the Iroquois Nations, in an area south of present-day Montreal. Jartoux’s letter suggested that “if [ginseng] is to be found in any other Country in the World, it may be particularly in Canada, where the Forests and Mountains … very much resemble these here.”2

Lafitau’s interest was piqued, and he began searching for the plant in the spring of 1716. He eventually recognized the plant late that summer when he noticed the bright crimson berries Jartoux had described. Lafitau preserved specimens of his find in eau-de-vie and shipped them to Paris. His memorandum on his discovery was shared with the Royal Academy of Sciences in January 1717, but it was met with skepticism. Merchants ignored the skeptics; Canadian ginseng was aboard a clipper ship bound to China in 1717. Profits from the sale of American ginseng in China were astronomical. French traders, who already had an established network for purchasing furs from indigenous tribes and trappers in Canada, paid about 3 francs per pound for ginseng root that was eventually sold in Canton for 180 francs per pound. The Canadian ginseng trade exploded and grew rapidly year after year. The results were devastating, at least from the ginseng’s point of view. Canadian ginseng sales peaked in 1752 and then dropped precipitously. Canadian ginseng was effectively extinct.3

Financial Incentive, Financial Gamble

There is an expression still used in Quebec that that originated with the ginseng market crash of 1752: “C’est tombe comme le ginseng,” which translates as, “It went down like the ginseng.”4 As the Canadian ginseng vanished, the wild harvesting moved south into the United States. Ginseng, as it turns out, grew wild in most states east of the Mississippi River (except Florida).

Ginseng was found in New England in 1750, and then in Western New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts the following year. Ginseng quickly became the second most important export for Colonial America, second only in value to fur. The frontiersmen Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone both made their fortunes as ginseng traders. While American ginseng never disappeared as thoroughly as the Canadian wild supply, it became extremely rare.5

Wisconsin farmers began growing ginseng in the late 1800s, using shaded canopies to imitate a forest setting. Large-scale ginseng farming began with the Fromm brothers in Wisconsin in 1904.6 Wisconsin farmers now harvest about a million of pounds of ginseng each year, of which 95% is exported to China. Or, more accurately, it was exported, as the recent trade war has left a question mark after this statement.7 This farmed ginseng, although valuable, is considered inferior to wild ginseng. Rather than looking wrinkly and lumpy, kind of like an old man, the farmed root is smooth – more reminiscent of a parsnip. The high-density farmed production is stressful to the plants, leaving them vulnerable to fungal infection.

One rapidly expanding ginseng production category is referred to as “wild simulated ginseng.” This refers to ginseng that has been purposefully planted in the forest, its natural habitat, and then left alone to fend for itself. This is not a new concept. People have been stewarding wild populations and replanting ripe berries for centuries.”6 This sort of forest-grown ginseng has a similar gnarly appearance to wild ginseng and is comparably priced.

Planting and stewarding ginseng remains something of a financial gamble. It takes about $15 000 to plant a half-acre, and the “farmer” may need to wait nearly a decade to harvest the roots before realizing a $50 000 return on that investment.8 During that entire period, the crop is vulnerable to predation from deer, rodents, wild turkey slugs, and – as the plants mature – poachers. Still, if everything works out, this isn’t the worst return on an investment, especially these days. According to some promoters, current market demand for tiny ginseng roots that are sold for replanting is so lucrative that the careful thinning of these immature roots and the selling of collected seeds might yield $100 000 in the 6-year period while the plant roots mature.9

There is little question that the human relationship with ginseng continues to be driven by the pursuit of financial gain.

American ginseng is now the most valuable non-timber crop in Eastern North America. This fact continues to keep ginseng in a most precarious position, as the plants do not replace themselves until they reach about 10 years of age. Three centuries of overharvesting have left what few wild plants there are in a precipitous position. The extremely high value and often remote location of these “forest farms” makes them a tempting target for poachers.

There are interesting developments occurring in the world of ginseng. This current enthusiasm for wild-simulated ginseng is part of a resurgence of interest in a broader agricultural category called Forest Farming, and ginseng is the prime sustainable crop that advocates are promoting as the poster child. One example of a large commercial Forest Farm venture is the American Ginseng Pharm in upstate New York, which has planted over 200 acres of wild simulated ginseng across a 1000-acre range in the Catskill Mountains. Ginseng isn’t their sole crop; according to their website, they are producing a range of medicinal products, all of which we are familiar with, including goldenseal, Coriolus, reishi, and cordyceps. The latter fungi, which may fetch a price of $15 000 to $20 000 per kilo, is certainly not being forest grown or, more aptly, caterpillar grown. Instead, the company “… grows the mushrooms exclusively on non-GMO, gluten-free organic grain in sterile, controlled rooms with an ambient climate that mimics that of the mountain valleys of the Himalayas.”10

It still kind of feels as if it is all about the money – what my neighbor, the psychotherapist, might describe negatively as “another transactional relationship.” At least in this wild-simulated business, the money incentive may drive ginseng’s survival rather than its eradication, and we can regard this as a good thing. We might also add that the preservation of forest is also advanced.

My Own Little Patch

I recently ordered some-1500 ginseng seeds online that I hope to get into the ground this coming September.11 My hope is that if I plant them quickly enough, I will have time to plant a second order before the ground freezes. I’m feeling a bit old and creaky for this sort of stoop labor. Perhaps I should have made a smaller order? Sometimes one gets carried away by an idea.

Odds are that less than half of these seeds will germinate, sprout, and survive. The odds are also low that I will be able to, or even want to, harvest these plants nearly a decade in the future. My goal is simply to be able sit in the woods and feel what a forest carpeted with ginseng has to say for itself. I suspect that there will be a richness to that experience that is worth the money and effort. Or I hope so. The idea of leaving a small section of forest a bit more complete and whole strikes me as reward in itself. Sometimes one does a thing in one’s life that is not clearly for gain; one just wants to do something purposeful to help transform the world and maybe leave it a richer place, even if is just a small patch of forest in the middle of nowhere.

References:

- United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service. Plants Database. Panax guinquefolius L. USDA Web site. https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PAQU. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Du Halde JP, ed. Edifying and Curious Letters, Written From Foreign Missions: Memoirs of China. Paris, France: A Paris; 1713. [Book in French]

- Parsons CM. The Natural History of Colonial Science: Joseph-François Lafitau’s Discovery of Ginseng and Its Afterlives. The William and Mary Quarterly. 2016;73(1). Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/608891. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Pritts KD. Ginseng: How to Find, Grow, and Use America’s Forest Gold. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books; 2010.

- Davis J, Persons WS. Growing and Marketing Ginseng, Goldenseal and other Woodland Medicinals. 2nd ed. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers; 2014.

- Fromm Bros. Historical Preservation Society. Wisconsin’s very own fairy tale. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20150209105349/http://frommhistory.org/story.html. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Dahdah J. Wisconsin ginseng industry hurt by trade war with China. December 19, 2019. Spectrum News 1. Available at: https://spectrumnews1.com/wi/madison/news/2019/12/20/wisconsin-ginseng-industry-at-mercy-of-trade-war-with-china. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education. Progress report for GNE19-221: Importance of Environmental Factors on Plantings of Wild-Simulated American Ginseng. 2020. SARE Web site. https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/gne19-221/. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- Profitable Plants Digest. A High Value Crop with Long Term Potential! 2020. Available at: https://www.profitableplantsdigest.com/ginseng/. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- American Ginseng Pharm. July 28, 2019. [Facebook post] Available at: https://m.facebook.com/Americanmagicginseng/posts/961068890908967. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- Wildgrown. Grow Your Own Ginseng! Available at: https://www.wildgrown.com/. Accessed June 21, 2020.

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO, graduated from NCNM in 1991 and has practiced in Denver, CO, ever since. He has been active in state association politics, taking his turn as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Doctors and Legislative Chair. Dr Schor has also held leadership positions in the Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, served on the AANP Board of Directors, and chaired the AANP’s speaker selection committee. For the past decade he has been the Associate Editor of the Natural Medicine Journal, and is a regular contributor to the Townsend Letter.