Education

David J. Schleich, PhD

The monolith that is the biomedicine industrial complex in America costs hit 18.2% in 2018, regardless of the irrefutable data about growing chronicity and the poor health of young people and boomers alike. (Statistics Portal, 2019) The European Union average is about half that. (Nuffield Trust, 2017) In fact, projected annual US per capita health-spending will reach almost $12K this year. (Kamal et al, 2018) This profitable US juggernaut shuffles with impunity through the retail corridors of the health industry in America, yanking from every shelf anything with a potential sustainable cash flow, and dismissing competing groups and ideas that get in its acquisitive way.

Despite Section 2706 in the post-ACA world, 2 biomedicine players – the AMA and the biopharmaceutical industry – have consistently challenged other professional groups and producers, even when they have something to contribute. The evidence of detraction about nutrition, smoking, spirituality in medicine, and even the energetics of homeopathy and Chinese medicine, are stacked on high over the decades, notwithstanding continuing growth in public use. (NCCIH, 2018) Yet, in recent years allopathic medicine’s newest acceptance of the dangers of inflammatory foods such as wheat, and the potential of mind-body medicine, long valued and protected in practice by the heterodox professions, are newly monetized and celebrated.

In the middle of such a turbulent, competitive health services marketplace, the educational leaders of non-MD professional bodies have been looking closely, yet again, at the stacked deck of biopharma and biomedicine. They are noticing (with more realpolitik in those same backpacks) the not so subtle migration of branding language from natural medicine into “integrative medicine.” Integrative medicine, as a moniker, is less affronting than its predecessor, “complementary and alternative medicine.” At least there is in the terminology a sense of things coming together. The sheer size and arrogance of mainstream biomedicine, however, continues to assimilate whatever it chooses, not apologizing or even acknowledging its earlier positions on, say, “food as medicine.” I have characterized the dominant, orthodox profession more than once as “clever rascals.”

This play for natural medicine principles and practice has already affected both camps, though. The professional agencies of non-MD professions are inclined not to rock the boat, wanting to build value propositions into interprofessional collegiality and stake a claim in the healthcare terrain. Those entering the medical professions are confused by the contrary imperatives of groups both claiming the high ground in mind-body medicine or food as medicine, for example. The “heterodox professions,” as Hans Baer called them 2 decades ago (Baer, 2001), drift toward the more orthodox. On the one hand, research into natural medicine protocols, theories, therapeutic order, and clinical practice grows; however, on the other, the inclusion of pharmacy and the proliferation of testing constitute a worrying blend to many traditional naturopathic and natural medicine practitioners. For many biomedicine professionals, for example, “prevention” means more tests sooner, rather than powerful lifestyle choice changes which span a lifetime and affect everything from life/work balance to food choice. While the allopathic mainstream adds momentum to its assimilation of modalities and approaches to treatment long eschewed by their political and regulatory arms, and often in the name of “new” science, the healthcare landscape is the worse as a minefield of competition and confusion proliferates, especially for the consumer. The tension is palpable, especially in the southeast United States, where the data about health markers are grim. Other regions of the country progressively enhance choice as one way to slow down the juggernaut. As a case in point, within the last decade the following states have added naturopathic medicine to the available choices of citizens: Minnesota, Colorado, North Dakota, Maryland, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania. Legislation is pending in North Carolina and New York, and is planned in 13 more states from one coast to the other.

The Essence of the Mater

Just what is the essence of this sharpening tension, then, characterized as it is by sorties into areas of nutrition and mind-body medicine long studied and successfully practiced by what have long been considered heterodox groups? How is it that the non-material elements in health outcomes are now more acceptable to the reductionist medical paradigm? It’s all in the evidence, not just the cost.

Perhaps a helpful descriptor in our deliberations about this process of assimilation is the word “quintessence,” rather than essence. The former word comes from the Latin words quinta and essential, meaning: 5 elements. When ancient Greek philosophers were contemplating what the universe was made of, they settled on 4: earth, air, fire, and water. Later physicists and mathematicians added a fifth, less familiar essence, or element – dark matter. However, even they, buoyed by the tools of science (as the heterodox professions have also been doing robustly and more often in the last 2 decades), are still not sure, for example, what dark energy and dark matter are ultimately all about, or exactly how to quantify the biopsychosocial factors that convert thought and emotion to physical response and health outcomes. Even so, Einstein and others, such as Vesto Slipher and Edwin Hubble, worked up their formulae into which they injected, as needed, something called the “cosmological constant” – which has proven to be anything but constant. Einstein was the first to use the Greek symbol, lambda (λ), to account for it in his calculations. He knew, and investigators ever since have known, that the value of lambda keeps shifting. Naturopathic doctors, as a profession, have long welcomed λ and all it implies. This development in the therapeutic order is promising.

Five Elements of Naturopathic Medical Curricula

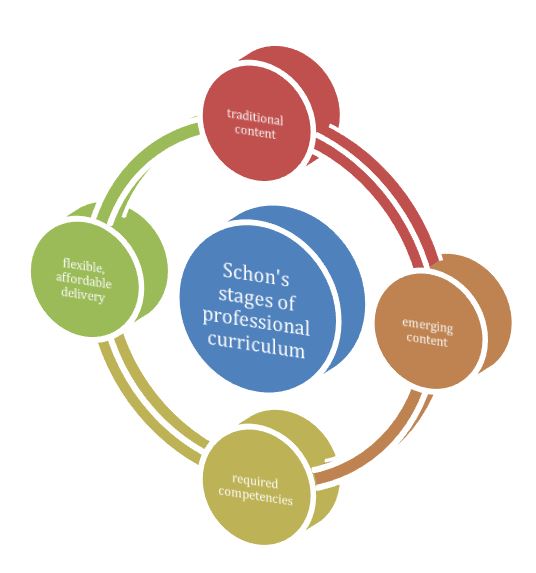

Important in the realpolitik of what is happening in health care worldwide, however, and to which naturopathic and other heterodox medical educators are paying increasing heed, are the rapidity, volume, and persistence of scientific innovation, patient centricity, evidence, big data, and emerging technology. However, before we drill more deeply into the detail of these variables, let us review what we’ve been working with all these years as we have shaped and delivered naturopathic medical education in that testy terrain. Four key elements of accredited naturopathic medical curricula around North America are well known:

- traditional theoretical content (our roots, reflected broadly in the writings of the early naturopathic profession)

- emerging content incrementally built over time and nourished by advancing clinical practice (which in turn finds its way into our classrooms via teachers and texts), naturopathic medical research (which translates into new approaches, modalities, tools, and techniques communicated by studies, seminars, lectures, CEUs, and the like)

- required competencies reflecting the politics and requirements of professional practice, public policy, and regulatory frameworks

- flexibility and affordability of delivery

The Fifth Element

A fifth element of sociopolitical pressure also has to be adjusted every once in a while to keep pace with the constant change in the direction, shape, and size of the curriculum universe. This, in turn, affects and contains the profession by virtue of producing graduates whose skills have to translate into effective practice. For example, naturopathic physicians are primary care professionals in a number of states. That recently earned status brings with it accountabilities and new tools. That fifth element, in curriculum design terms, can be understood from another perspective, rather than by mere content and skill development reaction to legislative and public policy changes.

Donald Schon’s landmark work, The Reflective Practitioner (Schon, 1987) is particularly useful in navigating those intersecting waves of regulation, tradition, and competition which hit the beachheads of the heterodox professions in different jurisdictions at different times. Collectively, these elements and Schon’s version of a “lambda” help describe naturopathic medical education as it manifests in our degree programs. In this regard, Schon’s work verifies that the tiers of professional curriculum repeat in all professions, ours included: basic sciences, applied sciences, and a practicum (Figure 1). Schon insists that no profession evolves in civil society without navigating these phases. The great challenge in all of this is that the form and content elements of the curriculum itself vary not only over time, but also from venue to venue in concert with the accreditation standards of the particular professions accreditor.

Figure 1. The 5 Formative Elements of Naturopathic Medical Curriculum

Schon contended that the phases of professional education repeat across an entire spectrum of occupations. In addition to pointing out the inevitable pressure of science in all professional preparation, Schon explains that the basic and the applied versions of the scientific content of curriculum occur in that order, followed by actual hands-on experience. Part of the context and background of the development of the curriculum of the naturopathic profession has been a sometimes divisive and always challenging debate about the “yearning” which many of the heterodox professions experience in their professional schools, namely, a “yearning for the rigor of science-based knowledge and the power of science-based technique” (Schon, 1987, p.9). Making the process even more unstable, as pointed out by Susan Lieff (2009), is that “the time lag between needs assessment and implementation of faculty development curricula assumes a certain stability of participants’ individual and contextual needs that may not reflect the often complex and shifting priorities in health professional schools.”

As Schon contended later (1995), “the greater one’s proximity to basic science, the higher one’s academic status.” Professional schools of medicine, in this regard, could easily set out to train healers and socialize them into a profession, but end up with biotechnical problem-solvers and not healers/physicians at all, with their art and science in hand. Routinely, the schools of medicine followed a sequence that immersed the student in basic and applied medical sciences and then in supervised clinical practice, all the while proclaiming “evidence-base.” This fascinating polarity has hugely influenced the development of naturopathic medical education in North America too.

The hegemony of Western medicine, Schon would maintain, has been sustained for a long time in this form, without overt coercion, via regulatory frameworks with vested interests and the accompanying power relationships. Ideas about “power and resistance” and what Schon describes as “zones of indeterminacy in practice that call for artistry but are bound by institutional commitments” (1987, p.115), may account for some of the eventual divergence from original curriculum intentions at our schools. In any case, it seems the “outline of professional preparation” (Schon, 1995) was as much the form of “requirements” for the naturopathic students at CNME-accredited schools, as for any allopathic medical student. In the end, naturopathic doctors have to go through “board exams” which are far away from clinical ecology and closer and closer to applied biological science. Ours is a stretchy universe of expanding curriculum. Lots of dark matter and dark energy out there.

Joining the Higher-Ed Mainstream

Hanna (2000) gives us an insight into the other variables that have been influencing our participation in the mainstream. He writes, “The university will be less inclined to base important decisions about programs and priorities strictly upon considerations of content and program quality” (Hanna, p.93) and more upon “what students, the adult marketplace and the university’s publics generally say they want from their university.” Earlier, Hanna set out what those new models would look like, basing them on analysis of trends observed in emerging organizational practice (Hanna, 2000, p.94):

- extended traditional universities

- for-profit, adult-centered universities

- distance education/technology-based universities

- corporate universities

- university/industry strategic alliances

- degree/certification competency-based universities

- global multinational universities

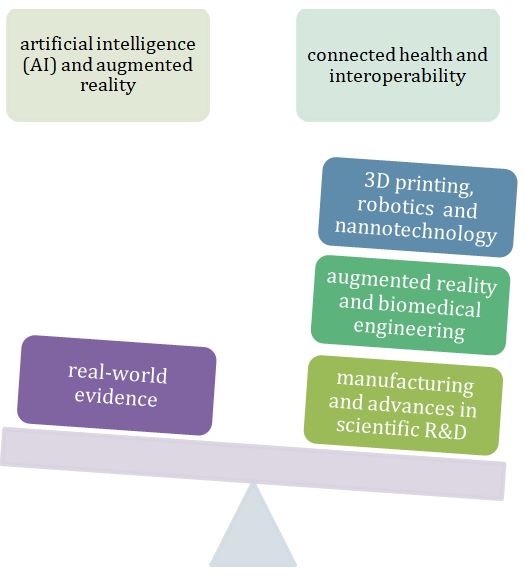

Hanna’s discussion of “extended traditional universities” builds on the work of Berquist (1992) and pretty much reinforces a notion that has evolved in our time, which is this: a time of transformation when the “traditional, content-based organization and decision-making within the university” (Hanna, p.99) will have to respond to a competitive higher-education environment – one in which our naturopathic colleges and naturopathic programs in small, comprehensive universities will also have to thrive, especially in view of emergent pressures such as AI, robotics, and “connected health.”

Among other powerful and interprofessional meta-themes in the normative medical curriculum is the study of what the goal of professional preparation for medical practitioners is. We accept that the medical profession’s purposes are as economically motivated as health-oriented; nevertheless, the very question of what health is arises when public policy permits disproportionately commodified systems as have evolved in North America. The nature of the US mainstream medical system presents with serious academic, economic, philosophical, and clinical questions, affecting naturopathic medical education structures at CNME-accredited schools and related medical curricula in the allied professions. Because of its curriculum content and design history, naturopathic medicine is uniquely positioned to cope with the wide array of factors rapidly reshaping the monolith referenced earlier (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Factors Affecting the Future of Medicine in America

Reflection in Action

Appropriately, then, Schon’s notion of “reflection-in-action” is very useful to get at what our education leaders are constantly forming in classroom and clinical curricula. As Schon states (1987), it is very difficult to separate identity from professional role. Naturopathic medical education is inevitably aligned with scientific professionalism and responds increasingly to this taxonomy of factors. Biomedicine and biopharma’s stacked deck has been a “guild-like” monolith in health design and delivery, but with diminishing credibility as efforts continue to co-opt holism and “natural” health systems and treatment. This pattern can be seen in the history of allopathic medicine and related industries since the time of Flexner (1910). Schon reminds us that “the relative status of the various professions is largely correlated with the extent to which they are able to present themselves as rigorous practitioners of a science-based, professional knowledge and to embody in their schools a version of the normative professional curriculum” (1987, p.9).

Krause’s contentions (1999) add some light to this multi-faceted conversation. His ideas help us to see that as naturopathic medicine continues to achieve social closure, as a profession its confrontation of that “guild power” could inexorably apply as much to the naturopathic profession as to any other group which strives to create institutions around its work. Power comes, Krause says, through dimensions of power over association, workplace, and market. Added to these is power over the relation to the state. The naturopathic profession increasingly fits into this political and social process quite handily. The fifth element keeps popping up no matter what we do.

We may yet have to dust off Schon’s “lambda” more than once in order to avoid the damage this accumulating muddle can cause to our roots and traditions. In the era of evidence-based medicine, the uncertainty about whether the 5 elements of curriculum are producing amazing naturopathic doctors rather than a subspecialty of holistic physicians is no small question. Even so, the game persists, and as we face the stacked deck of those who control the main turnstiles and cash flow of health care, the quintessential nature of naturopathic medicine may yet be figured out.

References:

Baer, H. (2001) Biomedicine and Alternative Healing Systems in America: Issues of Class, Race, Ethnicity and Gender. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Berquist, W. H. (1992). The Four Cultures of the Academy: Insights and Strategies for Improving Leadership in Collegiate Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Flexner, A. (2002). Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number Four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ, 80, (7), 594-602. .

Hanna, D. E. & Associates. (2000). Higher Education in an Era of Digital Competition: Choices and Challenges. Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

Kamal, R., Sawyer, B., & McDermott, D. How much is health spending expected to grow? December 12, 2018. Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker. Available at: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/much-health-spending-expected-grow/#item-annual-percentage-point-difference-growth-rates-makes-large-difference-spending-time_2016. Accessed January 8, 2019.

Krause, E. A. (1999). Death of the Guilds: Professions, States, and the Advance of Capitalism, 1930 to the Present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lieff, S. J. (2009). Evolving Curriculum Design: A Novel Framework for Continuous, Timely, and Relevant Curriculum Adaptation in Faculty Development. Academic Medicine, 84, 127-134.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Statistics from the National Health Interview Survey. Last modified November 8, 2018. NCCIH Web site. https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/NHIS. Accessed January 8, 2019.

Nuffield Trust. Current spending on health as a percentage of GDP in EU-15 countries. April 8, 2017. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/chart/current-spending-on-health-as-a-percentage-of-gdp-in-eu-15-countries. Accessed January 8, 2019.

Schon, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Schon, D. (Nov/Dec, 1995). Knowing-in-Action. The New Scholarship Requires a New Epistemology. Change, 27, 6, 2734.

The Statistics Portal. U.S. national health expenditure as percent of GDP from 1960 to 2018. 2019. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/184968/us-health-expenditure-as-percent-of-gdp-since-1960/. Accessed January 8, 2019.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).