By Alexis Chesney, MS, ND, LAc

Abstract

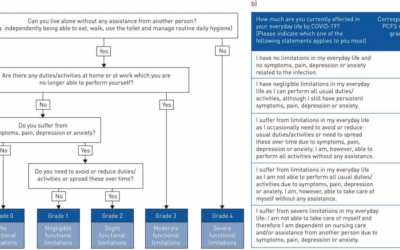

Babesiosis is an emerging tick-borne parasitic infection in the United States caused primarily by Babesia microti and Babesia duncani. Transmitted by Ixodes ticks, babesiosis has expanded beyond its traditional strongholds in the Northeast and upper Midwest, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently recognizing new endemic states, including Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Unlike bacterial infections such as Lyme disease, babesiosis is a protozoal infection that requires distinct diagnostic and treatment strategies. Clinical presentations range from asymptomatic infection to life-threatening disease, with risk factors for severe outcomes including immunosuppression, asplenia, and older age. Standard diagnostics include Giemsa-stained blood smears and PCR testing, while fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has emerged as a sensitive tool for detecting both acute and chronic infection. Treatment typically begins with pharmaceutical protocols, such as azithromycin plus atovaquone, but resistance, relapse, and chronic infection remain challenges. This article reviews the epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnostic modalities of babesiosis and outlines an integrative treatment approach that combines pharmaceuticals with evidence-based botanical medicine, anti-biofilm strategies, and supportive naturopathic care to improve patient outcomes and prevent chronic illness.

Introduction

Babesiosis, an emerging parasitic infection in the United States, is caused by Babesia microti and Babesia duncani. These intraerythrocytic protozoa are transmitted by blacklegged ticks – Ixodes scapularis (see Figure 1) in the Northeast and upper Midwest, and Ixodes pacificus (see Figure 2) in the West. In 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance summary formally recognized Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine as states with endemic babesiosis, reflecting the disease’s expanding epidemiologic impact.1

Proficiency in diagnosing and treating babesiosis is critical, given its fundamental distinction from Lyme disease. Unlike bacterial tick-borne infections, babesiosis is a parasite, requiring different treatment. Pharmaceutical treatment failures and resistance have been reported.2,3 Moreover, chronic babesiosis has been well documented, adding further complexity to patient management.2,3 As this protozoal infection becomes more prevalent, especially in the Northeast and upper Midwest, integrative practitioners must be prepared to accurately diagnose and comprehensively treat babesiosis.

An emerging tick-borne disease in the United States, it is imperative that healthcare providers become educated on the diagnosis and treatment of babesiosis. In this article, we will review the history, symptomatology, diagnostics, and treatment of babesiosis.

The History and Clinical Presentation of Babesiosis

Babesia is an intraerythrocytic protozoan parasite belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa, first described by the Hungarian pathologist Viktor Babes in 1888. 4 More than 100 Babesia species have been identified worldwide, including human-pathogenic species such as Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, and Babesia odocoilei. The first reported cases of babesiosis occurred in the United States in the 1960s, notably on Nantucket Island in Massachusetts.

Transmission of Babesia from an infected tick can occur in 36 hours after attachment.⁴ The incubation period of babesiosis generally ranges from one to six weeks. Clinical presentations can range from an asymptomatic infection to a fatal disease. Risk factors for severe babesiosis include asplenia, age over 50 years, immunosuppression, and coinfection with other tick-borne pathogens.⁴ Coinfection with Lyme disease is particularly common in regions where both pathogens exist.5

Patients with babesiosis may present with a range of symptoms, including fever, sweats, chills, fatigue, headache characterized by pressure, joint and muscle pain, and cough. Upon physical exam, splenomegaly may be found. Horowitz reports a hallmark tetrad of symptoms that flags babesiosis: excessive sweating or night sweats, heart palpitations, chest pain, and “air hunger,” described as difficulty breathing even at rest.6 Laboratory findings may reveal hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, and elevated liver transaminases.

The Diagnosis of Babesiosis

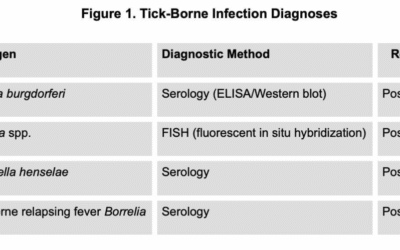

There are two standards of care within the medical community regarding the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme and tick-borne diseases. The conventional IDSA guidelines recommend a Giemsa-stained blood smear or PCR testing to confirm the diagnosis of babesiosis.7 Some healthcare providers, including many of my colleagues who are affiliated with the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), incorporate additional technologies, like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing, to support the diagnosis of babesiosis in their patients.6

I recommend using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which is a direct diagnostic technique used to detect Babesia ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The probes used in FISH are genus-specific, enabling detection of Babesia organisms regardless of whether the species is B. microti, B. duncani, or another member of the genus.

The IDSA 2020 Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Babesiosis states, “The diagnosis of babesiosis should be based on epidemiological risk factors and clinical evidence, and confirmed by blood smear examination or PCR.”7 Direct visualization of the parasite on a Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear is a classic diagnostic method, though it is rarely seen due to fewer than 1% of erythrocytes being infected in early disease.4 Thin blood smears have been reported to be 84% sensitive and 100% specific in acute babesiosis, but their use is more limited in chronic presentations.8

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing represents another direct diagnostic technology, targeting Babesia DNA in the bloodstream. PCR demonstrates approximately 95% sensitivity and 100% specificity, particularly when large-volume blood samples are tested for blood donor screening.8 However, PCR’s sensitivity is limited for detecting chronic babesiosis.

One significant advantage of FISH over PCR testing is its ability to discriminate between viable and dead or dying parasites because RNA is degraded more rapidly than DNA in dying cells.9,10 FISH technology will detect chronic babesiosis. Clinically, FISH has demonstrated a sensitivity of 98%, a specificity of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 99% when compared to the independent detection by Giemsa-staining.9

The Treatment of Babesiosis

My recommended treatment approach includes both a pharmaceutical antimicrobial component and a botanical anti-Babesia treatment. I generally begin with azithromycin and atovaquone, as outlined in IDSA guidelines, as it is better tolerated than the alternative regimen using clindamycin and quinine.7

The IDSA guidelines advise clinicians to treat a typical non-hospitalized patient experiencing a mild to moderate disease state with azithromycin at 500mg orally on day one and 250mg every 24 hours on subsequent days, plus atovaquone at 750mg orally every 12 hours for 7-10 days. However, the IDSA guidelines recommend that immunocompromised patients require at least 6 consecutive weeks of treatment and consider 500-1000mg daily doses of oral azithromycin. Retreatment with a different regimen is recommended “if infection relapses.”7 Furthermore, “B. duncani has low susceptibility to the four drugs recommended for treatment of human babesiosis, atovaquone, azithromycin, clindamycin, and quinine.”11 Horowitz recommends longer treatment regimens for babesiosis across the board.6

Let’s review the mechanism of action, cautions, laboratory monitoring, and side effects of the key pharmaceuticals azithromycin and atovaquone. Azithromycin is a macrolide that inhibits protein synthesis by binding reversibly to the P site on the 50S ribosomal subunit.12 Contraindications include hypersensitivity to macrolides, cholestatic jaundice, or hepatic impairment with prior azithromycin. It is recommended to take caution in a patient with a prolonged QT interval. Laboratory monitoring includes baseline hepatic function, complete blood count with differential, audiogram with prolonged use, and an electrocardiogram for QTc prolongation. Diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and hearing problems are the most common side effects experienced with azithromycin. Azithromycin is classified as Category B and is generally considered safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

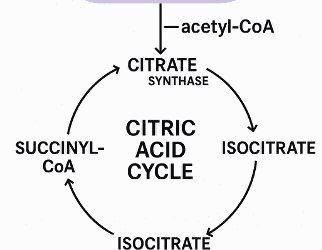

Atovaquone is an anti-protozoal that inhibits electron transport in the mitochondria, resulting in the inhibition of key metabolic enzymes responsible for the synthesis of nucleic acids and ATP.13 It must be taken with a fatty meal. Coenzyme Q10 must be avoided. Contraindications include hypersensitivity. One must be cautious with hepatic impairment. Laboratory monitoring includes hepatic function at baseline and monthly. Loose stool, abdominal pain, rash, and headache are possible side effects experienced with atovaquone. This medication is classified as Category C; however, maternal benefit exceeds the fetal/embryo risk, therefore it is not recommended to withhold it.14 Breastfeeding is generally considered safe.

In my clinical experience, I see the best outcomes when we initiate babesiosis treatment with azithromycin at 500mg once daily plus atovaquone at 750mg every 12 hours along with an anti-biofilm agent for 30 days, and then transition to botanical anti-Babesia treatment.

Naturopathic Treatment of Babesiosis

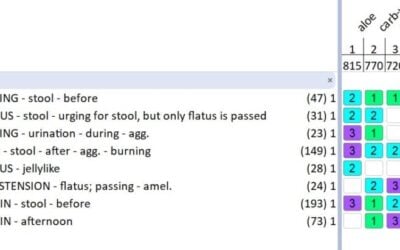

Given the limitations of pharmaceutical therapies and research supporting the efficacy of botanical medicine for babesiosis, my naturopathic approach incorporates a transition to natural therapies following an initial 30-day pharmaceutical-based protocol. Polygonum cuspidatum, Cryptolepis sanguinolent, Artemisia annua, Scutellaria baicalensis, Bidens Pilosa, and Sida acuta are evidence-based herbal tools that work in a myriad of ways in the treatment of babesiosis.15

Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese Knotweed) is a perennial plant, often recognized as an invasive species that many gardeners struggle to control. Interestingly, this plant thrives in areas where ticks are prevalent, and its roots offer medicine to those affected by tick-borne disease in these areas. Use of the whole plant is important, as it contains neuroprotective compounds such as resveratrol, polydatin, emodin, stilbenes, and anthraquinones. In addition to its anti-Babesia and anti-Borrelia effects15-17, the plant is anti-inflammatory, analgesic, immune-modulating, Herxheimer-reducing, and cardioprotective.18,19 Polygonum cuspidatum increases blood flow to the eyes, heart, skin, and joints, and crosses the blood-brain barrier.

Cryptolepis sanguinolenta is a climbing perennial with broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, including documented activity against Babesia and Borrelia.15,16,18-20 The important constituent indole alkaloid cryptolepine has antimalarial and antibacterial properties. Cryptolepis is immune-modulating, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, and protects the heart and the liver.

Artemisia annua (Sweet Annie) has demonstrated strong anti-Babesia and anti-Borrelia activity in studies conducted at Johns Hopkins.15,17 It also exhibits antifungal, antimalarial, antiviral, antiparasitic, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory properties. The constituents chrysospenol-D and chrysophlenetin impart anti-microbial effects. Artemisia annua activates CDK inhibitors, which prevent Babesia from invading the erythrocyte. Whole-plant use is recommended, as isolated artemisinin may promote resistance and has been associated with neurotoxicity at high doses over prolonged use. It is recommended to take three to seven days off per month of its use. Treatment with artemisinin in the 2nd and 3rd trimester was not associated with increased risks of congenital malformations or miscarriage and may be associated with a reduced risk of stillbirths compared to pharmaceutical antimalarials.21

Next, Scutellaria baicalensis (Chinese skullcap) is another effective herb used in the treatment of babesiosis and Lyme disease.15,16 Baicalein, wogonin, oroxylin A, baicalin, wogonoside, and oroxylin A-7-glucuronide are the constituents in the Chinese skullcap plant that hold anti-inflammatory properties.19 This plant has also been shown to improve convulsions, tremors, and neuralgias. It can be safely used in pregnancy.

Alchornea cordifolia (Christmas Bush), distinct from A. casaneifolia, possesses antimalarial, antibacterial, antiprotozoal, antifungal, anti-amoebic, and anti-inflammatory properties. Commonly used for respiratory, urinary, and gastrointestinal disorders, it has demonstrated inhibitory activity against Babesia.15 Protective of erythrocytes, Alchornea cordifolia has hemotonic, hemoregenerator, and hemoprotectant properties, and through these mechanisms also treats sickle cell anemia and African Sleeping Sickness.19

Bidens Pilosa (Spanish Needles) is a plant that contains polyacetylenes, which have an anti-malarial property.19 It exhibits antibacterial, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidant effects. Bidens Pilosa protects erythrocytes from oxidative damage and normalizes endothelial function during infections. This plant activates CDK inhibitors, which prevent Babesia from invading the erythrocyte.

Finally, Sida acuta (Common Wireweed) is a botanical source of cryptolepine, an antimalarial alkaloid.19 It possesses antiprotozoal, antibacterial, hematotonic, hematoregenerative, hematoprotectant, and anti-inflammatory properties. Notably, Sida acuta neutralizes Bothrops atrox snake venom, a hemotoxin that destroys erythrocytes.

To learn more about side effects, contraindications, and drug interactions of the botanical medicine mentioned above, refer to the works of herbalist and author Stephen Buhner.18,19

After 30 days of the azithromycin and atovaquone regimen, I recommend transitioning to two botanical formulas and continuing an anti-biofilm strategy. The first formula is an extract combining Polygonum cuspidatum, Cryptolepis sanguinolent, Scutellaria baicalensis, Bidens Pilosa, and Sida acuta in equal parts. The dosage for this combination tincture is 1 teaspoon three times daily on an empty stomach. In addition, I recommend Artemisia annua at 1 dropper three times daily on an empty stomach, pulsed three weeks on, followed by one week off.

In addition to antimicrobial pharmaceutical and botanical strategies, incorporating anti-biofilm interventions throughout the treatment plan is essential. Biofilm formation is recognized as one mechanism contributing to the persistence of babesiosis.22 Agents such as serrapeptase23,24 (500 mg or 120,000 units) or lumbrokinase (300,000 units), taken twice daily on an empty stomach, serve as effective fibrinolytic tools to help disrupt biofilm structures. By breaking down biofilm, these agents can increase the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapies by exposing sequestered parasites to treatment.

As a naturopathic physician, I take a whole-person approach to babesiosis treatment, looking beyond antimicrobial strategies to promote comprehensive healing. Detoxification support, as well as erythrocyte and endothelial protection, are key components of care throughout the course of treatment. Individualized treatment is paramount. In my clinical experience, optimal outcomes are achieved when pharmaceutical therapies are initiated promptly following diagnosis, continued for one to three months depending on the severity of the case, and then transitioned to targeted botanical protocols. It is essential to treat for two months after the resolution of symptoms.

As the incidence of babesiosis continues to rise in the United States, it is increasingly important for healthcare providers to be equipped with the most effective diagnostic and treatment strategies. Botanical medicine, supported by research, offers a critical next step following pharmaceutical antibiotic protocols. Naturopathic medicine is uniquely positioned to provide individualized care for patients with babesiosis, helping to prevent long-term illness and restoring full health.

Alexis Chesney, MS, ND, LAc, is a naturopathic physician, acupuncturist, author, and educator specializing in Lyme and vector-borne disease. Dr. Chesney enjoys getting to the root cause of complex chronic illness and partnering with patients to find wellness. She has a telehealth private practice and is on staff at Sojourns Community Health Clinic in Vermont. She serves as a trainer for the ILADEF Physician Training Program. Dr. Chesney is the author of Preventing Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases, released through Storey Publishing, and speaks on vector-borne diseases at conferences and in the media. You may find her at www.dralexischesney.com.

References

- Swanson M, Pickrel A, Williamson J, Montgomery S. Trends in reported babesiosis cases—United States, 2011–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(11):273–277. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7211a1.

- Simon MS, Westblade LF, Dziedziech A, et al. Clinical and molecular evidence of atovaquone and azithromycin resistance in relapsed Babesia microti infection associated with rituximab and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(7):1222–1225. doi:10.1093/cid/cix477.

- Krause PJ, Gewurz BE, Hill D, et al. Persistent and relapsing babesiosis in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(3):370–376. doi:10.1086/525852.

- Vannier E, Gewurz BE, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22(3):469–ix. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.010.

- Curcio SR, Tria LP, Gucwa AL. Seroprevalence of Babesia microti in individuals with Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16(12):737–743. doi:10.1089/vbz.2016.2020.

- Horowitz, Richard I. How can I get better?: An action plan for treating resistant Lyme and chronic disease. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2017.

- Krause PJ, Auwaerter PG, Bannuru RR, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): 2020 guideline on diagnosis and management of babesiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):e49–e64. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1216

- Krause PJ, Telford S 3rd, Spielman A, Ryan R, Magera J, Rajan TV, Christianson D, Alberghini TV, Bow L, Persing D. Comparison of PCR with blood smear and inoculation of small animals for diagnosis of Babesia microti parasitemia. J Clin Microbiol. 1996 Nov;34(11):2791-4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2791-2794.1996. PMID: 8897184

- Shah JS, Mark O, Caoili E, Poruri A, Horowitz RI, Ashbaugh AD, Ramasamy R. A Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) Test for Diagnosing Babesiosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Jun 6;10(6):377. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10060377.

- Shah JS, Caoili E, Patton MF, et al. Combined Immunofluorescence (IFA) and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Assays for Diagnosing Babesiosis in Patients from the USA, Europe and Australia. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(10):761. Published 2020 Sep 28. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10100761

- Abraham A, Brasov I, Thekkiniath J, et al. Establishment of a continuous in vitro culture of Babesia duncani in human erythrocytes reveals unusually high tolerance to recommended therapies. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(52):19974–19981. doi:10.1074/jbc.AC118.005771.

- Azithromycin (systemic): Drug information. In: UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer. (Accessed July 5, 2025.)

- Atovaquone: Drug information. In: UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer. (Accessed July 5, 2025.)

- Taylor WRJ, White NJ. Antimalarial drug toxicity. Drug Saf. 2004;27(1):25–61. doi:10.2165/00002018-200427010-00003.

- Zhang Y, Alvarez-Manzo H, Leone J, Schweig S, Zhang Y. Botanical Medicines Cryptolepis sanguinolenta, Artemisia annua, Scutellaria baicalensis, Polygonum cuspidatum, and Alchornea cordifolia Demonstrate Inhibitory Activity Against Babesia duncani. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:624745. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.624745

- Feng, Jie et al. “Evaluation of Natural and Botanical Medicines for Activity Against Growing and Non-growing Forms of B. burgdorferi.” Frontiers in medicine vol. 7 6. 21 Feb. 2020, doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00006

- Huang WY, Cai YZ, Xing J, Corke H, Sun M. Comparative analysis of bioactivities of four Polygonum species. Planta Med. 2008 Jan;74(1):43-9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993759.

- Buhner, SH. Healing Lyme. Silver City, NM: Raven Press, 2015.

- Buhner, SH. Natural Treatments for Lyme Coinfections: Anaplasma, Babesia and Ehrlichia. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 2015.

- Osafo N, Mensah KB, Yeboah OK. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review of Cryptolepis sanguinolenta (Lindl.) Schlechter. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2017;2017:3026370. doi:10.1155/2017/3026370

- Kovacs SD, van Eijk AM, Sevene E, et al. The Safety of Artemisinin Derivatives for the Treatment of Malaria in the 2nd or 3rd Trimester of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0164963. Published 2016 Nov 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164963

- Schetters T. Mechanisms involved in the persistence of Babesia canis infection in dogs. Pathogens. 2019;8(3):94. doi:10.3390/pathogens8030094.

- Katsipis G, Pantazaki AA. Serrapeptase impairs biofilm, wall, and phospho-homeostasis of resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023;107(4):1373-1389. doi:10.1007/s00253-022-12356-5. PMID: 36635396.

- Carpentieri A, Seganti L, Pucci P, et al. Protease treatment affects both invasion ability and biofilm formation in Listeria monocytogenes. Microb Pathog. 2008;45(1):45-52. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2008.01.007. PMID: 18479885.