S.A Decker Weiss, NMD, FASA, PLC

A complex ischemic cardiomyopathy case exploring myocardial recovery through guideline-directed medical therapy, device support, metabolic optimization, and experimental regenerative adjuncts.

Abstract

This case report examines significant functional improvement in a patient with severe heart failure with reduced ejection fraction following myocardial infarction, managed with optimized guideline-directed medical therapy, cardiac resynchronization therapy, and integrative metabolic and nutraceutical support. The case highlights emerging possibilities for myocardial recovery while emphasizing that regenerative and biologic therapies remain investigational adjuncts rather than established standards of care.

Introduction:

In general, skeletal muscle heals far more quickly and completely than cardiac muscle because it retains a robust regenerative capacity that the heart largely lacks.

Skeletal muscle repair begins within hours to days after injury. For mild to moderate injury (e.g., strain or contusion), functional recovery typically occurs within 2–6 weeks, while more severe tears may require 8–12 weeks or longer, depending on injury size, vascular supply, and rehabilitation. Importantly, regeneration can restore near-normal structure and function when the injury environment is favorable.1,2

In contrast, cardiac muscle has minimal intrinsic regenerative capacity. Following myocardial injury—most notably myocardial infarction—irreversible cardiomyocyte loss occurs within minutes, and healing proceeds primarily through fibrotic scar formation rather than true muscle regeneration. The inflammatory and proliferative phases occur over weeks, but the resulting scar is permanent and non-contractile; ventricular remodeling and functional consequences can evolve over months to years.3,4 Thus, while skeletal muscle healing restores tissue, cardiac “healing” stabilizes the injury at the cost of contractile reserve.

An additional factor in ischemic cardiomyopathy is mitochondrial dysfunction. In skeletal muscle, mitochondria are highly adaptable and closely linked to regeneration. After injury, satellite cell activation and myoblast differentiation require a metabolic shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation, accompanied by mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling. Healthy mitochondrial dynamics (fusion, fission, mitophagy) support efficient ATP production, limit reactive oxygen species (ROS), and promote successful myofiber regeneration. When mitochondrial function is impaired—such as with aging, diabetes, or ischemia—skeletal muscle healing is slower and more incomplete.5,6

In cardiac muscle, mitochondria occupy ~30% of cardiomyocyte volume and are essential for continuous high-output ATP generation. Following myocardial infarction, ischemia and reperfusion cause profound mitochondrial injury, including loss of membrane potential, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), and excessive ROS generation. These events trigger cardiomyocyte death and sharply limit any regenerative response. Surviving cardiomyocytes must increase workload with damaged mitochondrial networks, contributing to adverse ventricular remodeling and progression to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).7,8 Unlike skeletal muscle, cardiomyocytes have extremely limited capacity to replace lost cells or reset mitochondrial populations at scale.

Background:

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a clinical syndrome of heart failure characterized by impaired left ventricular systolic function, typically defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%, with accompanying symptoms/signs of congestion or low cardiac output.9 In the context of myocardial infarction (MI), HFrEF commonly develops from ischemic cardiomyopathy: irreversible myocyte loss from infarction, followed by adverse left ventricular remodeling (dilation, wall thinning, and progressive contractile dysfunction) that can culminate in chronic systolic heart failure.10 In the United States, heart failure overall affects an estimated ~6.7 million adults, and HFrEF represents roughly half of heart failure cases (with the remainder largely HFpEF/HFmrEF, varying by age/sex and comorbidity).11,12

Background Theory

This is the simple version of the strategy to help this patient recover.

- Keep him alive, and support positive myocardial remodeling – implant the device (CRT-D)

- Use medications to back off the neurohormonal response to heart failure.

- Use nutrition and nutritional supplements to decrease risk factors, replenish magnesium, decrease inflammation and oxidative stress, support mitochondrial health and support the management of neurohormonal dysfunction.

- Use NAD+ and slow release T3 (liothyronine) for mitochondrial support.

- Use MSC-derived exosomes and amniotic membrane for regeneration.

Neurohormonal Response to Heart Failure

Ischemic myocardial infarction leads to loss of viable myocardium, reduced cardiac output, and increased ventricular wall stress, activating maladaptive neurohormonal pathways that drive heart failure progression. Reduced renal perfusion stimulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), promoting vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and adverse ventricular remodeling, while sympathetic nervous system overactivation increases myocardial oxygen demand, arrhythmic risk, and myocyte apoptosis. Persistent elevation of angiotensin II, aldosterone, and catecholamines perpetuates inflammation, fibrosis, and progressive systolic dysfunction.13-15 In parallel, mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired myocardial energetics are now recognized as central contributors to ischemic cardiomyopathy, compounding contractile failure and limiting adaptive reserve.16

The four pillars of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) directly counter these processes and improve survival. Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (as well as ACE inhibitors/ARBs) suppress RAAS signaling and attenuate adverse remodeling while enhancing natriuretic peptide activity.17 Evidence-based beta-blockers blunt sympathetic overactivation and reduce sudden cardiac death.18 Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists inhibit aldosterone-mediated sodium retention and myocardial fibrosis.19 Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors further reduce heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality, with emerging evidence suggesting favorable effects on myocardial energetics and systemic inflammation.20 Together, these therapies address the dominant neurohormonal drivers of ischemic heart failure.

Adjunctive nutraceutical and botanical therapies may complement GDMT by supporting mitochondrial function and autonomic balance. Ubiquinol (reduced coenzyme Q10), an essential component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, has demonstrated reduced cardiovascular mortality and improved functional outcomes in randomized trials of chronic heart failure.21 Magnesium, a critical cofactor for ATP-dependent processes and myocardial electrical stability, is frequently deficient in heart failure and post–myocardial infarction states, with repletion associated with reduced arrhythmias and improved outcomes.22 Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) has been shown in human and translational studies to support mitochondrial biogenesis and redox signaling, though large outcome trials remain limited.23 Certain cardiotonic botanicals have also been historically used to influence myocardial performance and neurohormonal tone. Convallaria majalis contains cardiac glycosides that enhance contractility through Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase inhibition, while Leonurus cardiaca (motherwort) exhibits mild negative chronotropic and anxiolytic effects that may attenuate sympathetic overactivity. While these agents should be considered supportive rather than disease-modifying and require careful clinical judgment, they illustrate a complementary approach targeting both myocardial energetics and neurohormonal stress in ischemic heart failure.

Devices

Device-based therapies are an integral component of treatment for selected patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), particularly those who remain symptomatic despite optimized guideline-directed medical therapy. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) reduce mortality by preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with LVEF ≤35% through termination of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves mechanical synchrony in patients with reduced LVEF and prolonged QRS duration—especially left bundle branch block—resulting in reverse remodeling, improved functional capacity, reduced hospitalizations, and lower mortality. In patients who are not candidates for CRT or who remain symptomatic, emerging neuromodulatory and contractility-enhancing therapies provide additional options: cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) delivers nonexcitatory electrical signals during the absolute refractory period to augment myocardial contractile strength and improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and baroreflex activation therapy (Barostim) electrically stimulates the carotid baroreceptors to restore autonomic balance by reducing sympathetic activity and enhancing parasympathetic tone, leading to improvements in functional status and heart failure symptoms.24-29

Reasons for Optimism

For most of the author’s career, there has been little hope for patients in heart failure other than long shot therapies and transplants (transplants are complex and are not a preferred option). Presently the medications are significantly improved, the devices are effective and are becoming more effective as the technology develops; natural models such as NAD+, herbals, and orthomolecular products can provide a more predictable support than ever before. By adding in possible regeneration, HfREF is no longer a hopeless diagnosis but rather is becoming a process for a slow recovery with a significant improvement in quality of life.

Patient Information and Presenting Concern

A 64 year old male presented with a wearable cardioverter-defibrillator, or a LifeVest which was assigned from his cardiologist and transplant surgeon due to his heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. His ejection fraction was 15-20% (Normal is 55+/- 10%) (EF 15–20% + symptoms at rest, frequent decompensation → NYHA IV)

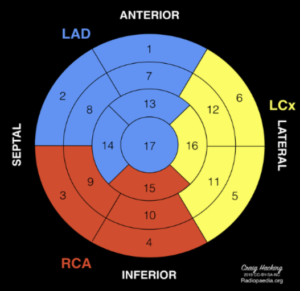

The patient had a myocardial infarction 4 months earlier with severe damage to the areas supplied by the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and a remote heart attack potentially affecting the mid circumflex region.

Diagnostic Assessment

Echocardiography:

| Segment # | Anatomic Segment | Wall Region | Motion Abnormality |

| 1 | Basal Anterior | Anterior Wall | Hypokinesis |

| 7 | Mid Anterior | Anterior Wall | Akinesis |

| 8 | Mid Anteroseptal | Anterior Septum | Akinesis |

| 11 | Mid Inferolateral | Lateral Wall | Hypokinesis |

| 12 | Mid Anterolateral | Lateral Wall | Hypokinesis |

| 13 | Apical Anterior | Apex | Akinesis |

| 14 | Apical Septal | Apex | Akinesis |

| 16 | Apical Lateral | Apex | Akinesis |

| 17 | Apical Cap | Apex | Akinesis |

Summary: Severely reduced left ventricular systolic function with an estimated ejection fraction of 15–20% due to extensive akinesis of the mid-anterior, anteroseptal, and apical segments, with additional hypokinesis of the basal anterior and mid-lateral walls.

Lab Assessment

Pertinent findings include:

-

- Homocysteine: 37 (optimal per the author is under 10)

- Hgb A1c: 6.8 (optimal per author is under 5.4)

- NT-Pro-BNP: 3987 (optimal under 100 per author)

- TSH: 19 (high) and Free T3: 1.8 (low)

- HS-CRP: 15.6 (under 2.0 ideal per author)

- oxLDL: 82 (under 40 ideal per author)

Therapeutic Intervention

Step 1: Optimize medication

The patient was moved from Metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice a day to carvedilol 6.25 mg twice a day (Beta/Alpha Blocker), Sacubitril/Valsartan 24/26 mgs (ARNI) 1 cap twice a day, Empagliflozin 25 mgs (SGLT2) once daily for blood sugar and cardiac remodeling support, and Finerenone (MRA) 10 mgs. Labs were monitored for BUN/Creatinine, electrolytes, and a CMP.

Step 2. Optimize Supplementation

-

- A methylation support supplement was started at 2 caps twice a day to reduce homocysteine and support healthy levels of neurotransmitters and glutathione levels.

- A combination vitamin E and herbal formula was added at 1 cap twice a day to reduce oxLDL (oxidative stress).

- A combination herbal formula with Convallaria majalis, Leonurus cardiaca, Craetegus spp., Melissa officinalis – 1 cap twice a day

- Magnesium (Slow Release Technology – Dimagnesium malate) 1 twice daily, with co-factored B’s for additional methylation support

Step 3: Mitochondrial Support

- PQQ (pyrroloquinoline quinone) – 10 mgs twice a day

- Ubiquinol – 200 mgs 4 times a day

- NAD+ – building to 40 mgs Sub Q three times a week

T3 (Liothyronine) slow release compounded (no glandular or Cytomel) 2.5 mcgs twice a day

CONTROVERSIAL: DO NOT DO THIS WITHOUT PROPER TRAINING AND MONITORING

Step 3:

CRT-D (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy–Defibrillator) implanted

Step 4:

MSC Derived Exosomes (extra cellular vehicles or ESV’s)

Patients were explained in detail that MSC derived exosomes (extra cellular vehicles or ESV’s) are experimental, and that safety and efficacy have not been evaluated and are not FDA approved for this condition. The patient(s) understood the discussion and signed a form of attestation.

MSC derived exosomes (extra cellular vehicles or ESV’s) were administered in two methods. (1) A Sub Q wheel was placed just lateral to the LLSB (350 Billion) and allowed to absorb while the patient was in a partial left lateral decubitus. The same amount was nebulized. Treatment repeated after 90 days

Step 3: Amniotic Membrane

Patients were explained in detail that this use of amniotic membrane is experimental, and that safety and efficacy have not been evaluated and are not FDA approved for this condition. The patient(s) understood the discussion and signed a form of attestation.

The cardiac apex area was mapped with POCUS echocardiography then cleaned with alcohol, allowed to dry, and “scuffed” to pain tolerance with a goal of erythema to the region. A 2.5 to 2.5 square amniotic membrane was first attached to a 3 cm by 3 cm Mepilex type soft silicone.

Treatment repeated after 90 days

Step 4. Nutrition

The patient was placed on an anti-inflammatory diet absent of trans fats and sugar.

Clinical Findings

-

- Homocysteine: 37 (optimal per the author is under 10) – dropped to 14

- Hgb A1c: 6.8 (optimal per author is under 5.4) – dropped to 5.8

- NT-Pro-BNP: 3987 (optimal under 100 per author) – dropped to 1524

- TSH: 19 (high) – decreased to 7

- Free T3: 1.8 (low) – increased to 2.3

- HS-CRP: 15.6 (under 2.0 ideal per author) – decreased to 9.0

- oxLDL: 82 (under 40 ideal per author) – decreased to 68

F/U Echocardiography

120 days – EF% increased to 35%

Echo repeated at 180 days as follows:

| Segment # | Anatomic Segment | Wall Region | Motion |

| 1 | Basal Anterior | Anterior Wall | Normal |

| 2 | Basal Anteroseptal | Anterior Septum | Normal |

| 3 | Basal Inferoseptal | Septum | Normal |

| 4 | Basal Inferior | Inferior Wall | Normal |

| 5 | Basal Inferolateral | Lateral Wall | Normal |

| 6 | Basal Anterolateral | Lateral Wall | Normal |

| 7 | Mid Anterior | Anterior Wall | Hypokinesis |

| 8 | Mid Anteroseptal | Anterior Septum | Hypokinesis |

| 9 | Mid Inferoseptal | Septum | Normal |

| 10 | Mid Inferior | Inferior Wall | Normal |

| 11 | Mid Inferolateral | Lateral Wall | Normal |

| 12 | Mid Anterolateral | Lateral Wall | Normal |

| 13 | Apical Anterior | Apex | Hypokinesis |

| 14 | Apical Septal | Apex | Hypokinesis |

| 15 | Apical Inferior | Apex | Normal |

| 16 | Apical Lateral | Apex | Normal |

| 17 | Apical Cap | Apex | Hypokinesis |

Green: Improvement in segment

Burgundy: Segment recovered

Left ventricular systolic function is mildly to moderately reduced with an estimated ejection fraction of 40–45% (EF 45–50% + asymptomatic → NYHA Class I), with hypokinesis involving the mid-anterior, anteroseptal, and apical segments and otherwise normal regional wall motion.

Safety and Tolerability

All types of interventions have an excellent history of safety and low adverse reactions and/or intolerability. The patient did not report any adverse reactions nor side effects other than soreness near the implanted device.

Safety Summary

Across emerging biologic and metabolic interventions for peripheral neuropathy, MSC-derived exosomes, NAD⁺, and amniotic membrane–based therapies demonstrate generally favorable early safety profiles but remain investigational for this indication. MSC-derived exosomes are considered potentially safer than live-cell therapies due to their acellular structure, low immunogenicity, and lack of replicative capacity, with preclinical studies and limited human reports showing few serious adverse events; however, concerns remain regarding product heterogeneity, bioactive cargo effects, and limited long-term data.30-35 NAD⁺ therapies, leveraging an endogenous cofactor central to mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis, are well tolerated in studies of oral precursors, while parenteral administration is mainly associated with transient infusion-related symptoms and lacks standardized dosing or FDA-approved indications.36-39 Amniotic membrane–derived biologics have a long clinical history in wound care and surgery with low immunogenicity and rare serious adverse events, though variability in processing methods and limited neurologic-specific data constrain conclusions for peripheral neuropathy.40-44 Rigorous manufacturing standards and controlled human trials are needed to further define safety and efficacy.

Comparative Safety Table

| Therapy | Key Safety Advantages | Reported Risks / Limitations | Regulatory Status |

| MSC-derived exosomes | Acellular; low immunogenicity; no tumorigenicity or ectopic tissue formation reported | Product heterogeneity; variable sourcing/isolation; limited long-term human data | No FDA-approved indications |

| NAD⁺ (parenteral & oral) | Endogenous molecule; good tolerability (oral); reversible adverse effects | Infusion-related symptoms; lack of standardized dosing; limited long-term injectable data | No FDA-approved injectable NAD⁺ |

| Amniotic membrane | Long clinical use; anti-inflammatory; low immunogenicity | Processing variability; limited neurologic outcome data; off-label neuropathy use | FDA-cleared for wound/surgical use, not neuropathy |

Discussion

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)–derived exosomes are being explored as a cell-free biologic for HFrEF and ischemic cardiomyopathy because they can deliver cardioprotective signaling cargo (eg, microRNAs, proteins, lipids) that may modulate inflammation, reduce apoptosis, and promote angiogenesis/remodeling in preclinical models; however, human evidence remains early, heterogeneous, and largely investigational, with ongoing work focused on manufacturing, dosing, and delivery challenges (eg, IV vs intracoronary vs intramyocardial) and on clarifying durable clinical endpoints.45-46 In parallel, NAD⁺ augmentation is being studied to address the mitochondrial/redox dysfunction that accompanies HFrEF; in a small clinical trial of stable HFrEF patients, the NAD⁺ precursor nicotinamide riboside substantially increased whole-blood NAD⁺ and appeared feasible/tolerable, but definitive benefits on remodeling, symptoms, hospitalizations, or mortality remain unproven and require larger trials (notably, the clinical evidence base is stronger for oral NAD⁺ precursors than for injectable NAD⁺ itself in HFrEF populations).47

Other adjunctive biologic/metabolic strategies are even less established. Amniotic membrane–derived biomaterials (and amnion-derived cell products) are being investigated primarily as bioactive scaffolds/patches that deliver growth factors and extracellular matrix signals, with most supporting data in cardiovascular disease coming from preclinical and translational work rather than robust HFrEF outcomes trials.48 Liothyronine (T3) has interest mainly in HFrEF patients with low T3 syndrome, where thyroid hormone signaling may influence contractility, vascular tone, and mitochondrial gene expression; current efforts include feasibility and randomized studies evaluating whether normalizing T3 is safe and signals functional benefit, but routine use is not guideline-standard and requires careful arrhythmia/ischemia risk consideration and endocrinology/cardiology oversight.49,50 Overall, these approaches should be framed as experimental adjuncts to—rather than replacements for—guideline-directed medical and device therapy in HFrEF.

Follow-up and Outcomes

The patient is due for follow-up echocardiogram in three more months, but another positive signal is that his lab numbers are still moving in the right direction, with an NT-proBNP of 1246. He is in cardiac rehabilitation, and his cardiac device shows no signs of arrhythmia.

Conclusion

The author would like to be clear that this is not hard science in the sense that it is observational, and that the raw data has not been properly crunched by a statistician. The author does not assume that a correlative or a causal relationship exists, just that what has been clinically observed is shockingly positive to this point. The author assumes that the lack of a blind, and the overall promotion of the therapies may have a placebo effect.

Dr. S.A. Decker Weiss, NMD, FASA is a board-certified naturopathic physician specializing in integrative cardiology and longevity medicine. He is the founder of the Weiss Heart & Longevity Clinic and serves as Executive Director of Global Medical. Dr. Weiss is a Fellow of the American Society of Angiology and was one of the first naturopathic physicians to complete a hospital-based cardiology rotation, helping pioneer the integration of naturopathic and conventional cardiovascular care. With more than two decades of clinical experience, he focuses on heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, lipid optimization, metabolic dysfunction, and advanced preventive cardiology. Dr. Weiss lectures internationally on integrative cardiovascular therapeutics and is committed to bridging evidence-based natural medicine with contemporary cardiac science.

Dr. S.A. Decker Weiss, NMD, FASA is a board-certified naturopathic physician specializing in integrative cardiology and longevity medicine. He is the founder of the Weiss Heart & Longevity Clinic and serves as Executive Director of Global Medical. Dr. Weiss is a Fellow of the American Society of Angiology and was one of the first naturopathic physicians to complete a hospital-based cardiology rotation, helping pioneer the integration of naturopathic and conventional cardiovascular care. With more than two decades of clinical experience, he focuses on heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, lipid optimization, metabolic dysfunction, and advanced preventive cardiology. Dr. Weiss lectures internationally on integrative cardiovascular therapeutics and is committed to bridging evidence-based natural medicine with contemporary cardiac science.

References:

- Chargé SBP, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):209-238. doi:10.1152/physrev.00019.2003.

- Tidball JG. Mechanisms of muscle injury, repair, and regeneration. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(4):2029-2062. doi:10.1002/cphy.c100092.

- Frangogiannis NG. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodeling. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(5):255-265. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28.

- Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473(7347):326-335. doi:10.1038/nature10147.

- Sin J, Andres AM, Taylor DJR, Weston T, Hiraumi Y, Kitsis RN. Mitophagy is required for mitochondrial biogenesis and skeletal muscle regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(9):3564-3576. doi:10.1172/JCI85054.

- Ryall JG, Schertzer JD, Lynch GS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and impaired regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(8):585-596. doi:10.1038/nrm2428.

- Ong SB, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial dynamics as a therapeutic target for treating ischemia–reperfusion injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;14(11):2225-2238. doi:10.1089/ars.2010.3313.

- Dorn GW II. Mitochondrial dynamism and heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(3):181-190. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2014.10.001.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063.

- Iannaccone M, Quadri G, Taha S, et al. Ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2022;24(11):1509-1520. doi:10.1007/s11886-022-01766-6.

- Martin SS, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149:e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209.

- Docherty KF, Jhund PS. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Lancet. 2025;406(10405):e1-e14.

- Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1990.

- Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure. Circulation. 2005.

- Braunwald E. Heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

- Neubauer S. The failing heart—an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med. 2007.

- McMurray JJV, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014.

- MERIT-HF Study Group. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1999.

- Pitt B, et al. Spironolactone for severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999.

- McMurray JJV, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2019.

- Mortensen SA, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in chronic heart failure (Q-SYMBIO). JACC Heart Fail. 2014.

- Rasmussen HS, et al. Magnesium and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1986.

- Harris CB, et al. PQQ and mitochondrial function in humans. J Nutr Biochem. 2013.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063.

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877-883. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013474.

- Cleland JGF, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(15):1539-1549. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050496.

- Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Uriel N, et al. Two-year outcomes with a magnetically levitated cardiac pump in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1386-1395. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800866.

- Kadish A, Nademanee K, Volosin K, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of cardiac contractility modulation in advanced heart failure. Am Heart J. 2011;161(2):329-337. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2010.10.025.

- Abraham WT, Zile MR, Weaver FA, et al. Baroreflex activation therapy for the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(7):753-763. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.015.

- Phinney DG, Pittenger MF. Stem Cells. 2017;35(4):851-858.

- Elahi FM, et al. Stem Cells. 2020;38(1):15-21.

- Lener T, et al. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:30087.

- Mendt M, et al. JCI Insight. 2018;3(8):e99263.

- Kordelas L, et al. Leukemia. 2014;28(4):970-973.

- Théry C, et al. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750.

- Verdin E. Science. 2015;350(6265):1208-1213.

- Trammell SAJ, et al. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12948.

- Dollerup OL, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(2):343-353.

- Grant R, Kapoor V. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;59:101036.

- Niknejad H, et al. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;15:88-99.

- Koob TJ, et al. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2014;102(6):1353-1362.

- Fairbairn NG, et al. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(5):662-675.

- Snyder RJ, et al. Wounds. 2016;28(11):E1-E10.

- Farjah GH, et al. Injury. 2022;53(3):1028-1035.

- Chen Y, Zhao Y, Wang Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes: a new era in cardiac therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15:Article 4123. doi:10.1186/s13287-024-04123-2.

- Guan A, Alibrandi L, Verma E, et al. Clinical translation of mesenchymal stem cells in ischemic heart failure: challenges and future perspectives. Vascul Pharmacol. 2025;169:107491. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2025.107491.

- (Trial) Safety and tolerability of nicotinamide riboside in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022. (Dose reported: 1000 mg twice daily; increased whole-blood NAD⁺; feasibility/tolerability outcomes).

- Amniotic membrane in cardiac diseases (bioactive scaffold concepts and translational applications). Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024.

- Developing Oral LT3 Therapy for Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (DOT3HF-HFrEF). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04112316. Updated December 16, 2024.

- The use of thyroid hormone liothyronine in patients with heart failure (feasibility study protocol/registry entry). ISRCTN10706683.