Michael Friedman, ND

Abstract

This case study explores the use of kava (Piper methysticum)and Rauwolfia vomitoria in two siblings with PTSD and ODD in an older child, and PTSD and ADHD in the younger child, following severe early-life trauma. Under naturopathic care, standardized kava extract and the use of rauwolfia vomitoria led to significant behavioral improvements, school reintegration, better grades, and discontinuation of prescription medications—without adverse effects.

Introduction

During my clinical training at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, I had the opportunity to learn from the late Dr. Abraham Hoffer, MD, PhD – a renowned psychiatrist and pioneer in orthomolecular medicine. One formative moment occurred when I presented a case involving a patient with liver cancer. I had recommended high doses of herbs and vitamins, a protocol my clinic supervisor was reluctant to approve. Dr. Hoffer, observing as a visiting professor that day, surprised us all. He suggested not only agreeing with my recommendations but doubling the dosages.

“There are two things the patient needs to be asked,” he said. “One, is he okay living longer? And two, is he willing to feel better?”

That patient’s case was later published in a medical journal after her twelve metastatic ocular melanoma tumors disappeared across 20 CT scans over a period of 18 months, treated solely with botanical and nutritional therapies. That experience shaped my clinical philosophy profoundly: when used appropriately, botanicals can yield transformational outcomes with minimal side effects.

This philosophy guided my approach to a more recent and challenging pediatric case involving siblings suffering from severe trauma-related disorders.

Case Presentation: Trauma, PTSD, and ODD in Siblings

I was consulted on the case of a nine-year-old girl with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), as well as her younger brother, aged seven, who had diagnoses of PTSD and ADHD. Both children had been abandoned by their parents at a young age following a traumatic incident in which they witnessed their father commit a homicide. Left alone in a hotel room without food or adult care, the older sister, then only four years old, took care of her toddler brother until hotel staff discovered them. Both parents were subsequently incarcerated, and the children were adopted.

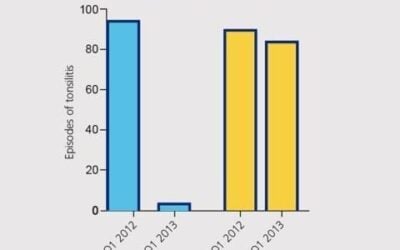

The older sibling exhibited intense behavioral dysregulation, particularly in response to any mention of her biological parents. These triggers resulted in aggressive outbursts—throwing chairs, smashing windows, and overturning desks. Due to these behaviors, she was suspended from public school and placed under psychiatric care, where she was prescribed clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist often used for ADHD and PTSD in children. The family was covered by Medicaid. The psychiatrist would spend five minutes virtually with the children per month, with no time for counselling or developing a relationship with the children. The drug required routine cardiac monitoring due to its potential side effects, including hypotension and bradycardia. The older sister hit the adoptive mother five times a week, and verbally abused the adoptive mother twice a week on average, while being treated by the child psychiatrist for ODD. The clonidine drug made no positive impact on the behavior, according to the adoptive mother and the school. Both children’s report cards at school showed most grades to range between 1(not meeting grade expectations) and 2 (working up to grade level expectations). After weaning off the drug clonidine in both children and taking a herbal supplement regimen, both children’s report cards went to mostly 3 (meeting grade level expectations) and 4 (exceeding grade level expectations). The adoptive mother was physically/verbally hit by the adoptive daughter three times during the first three months, versus three or four times a week. The younger brother with ADHD (mostly hyperactivity) was under much better control both in the home environment and within school. The adoptive mother called her herbal protocols “magic pills” as they transformed home life and academic life for the better with noticeable changes within two days. After the first three months of using these herbs, there was no physical or verbal abuse of the adoptive mother. There were no side effects reported in the weaning of the drug process of clonidine or any side effects noted with the herbal regimen. It would be exactly as my mentor, Dr Hoffer, said, “don’t spend your time worrying about hypothetical side effects and focus on the real side effects, feeling better.” Both children were able to stop the daily regimen within six months. Currently, the adoptive mother offers one to two capsules of Kava if the children say they feel they need the extra help that day with their moods. This is only needed a few times a month.

Botanical Intervention with Kava (Piper methysticum)

Given the family’s concern that the psychiatrist’s treatment of clonidine was not clinically effective, I recommended a simple yet targeted intervention: a standardized kava root extract 400 mg containing 30% kavalactone, providing 120 mg of kavalactones per capsule. The solvents used were ethanol.

Both children were given:

- 1 capsule (120 mg kavalactones) in the morning and one capsule upon return from school or 4 pm on the weekend

- Additionally, one capsule blend of rauwolfia vomitoria containing 25 mg mixed with an adaptogenic herbal blend with ashwagandha (in the formula below) was administered at the same time as the Kava capsules.

| Ashwagandha root extract (Withania somnifera)Withanolides 7.5mg | 500 mg | |

| Organic California PoppyAerial Parts (Eschscholzia californica) | 100 mg | |

| Organic Catnip Herb (Nepeta cataria) | 50 mg | |

| Organic Lavender Flower (Lavandula angustifolia) | 30 mg | |

| African Snake Root (Proprietary blend of rice flour) (Rauwolfia vomitoria) | 12 mg | |

| Organic Lemon Balm Leaf (Melissa officinalis) | 3 mg |

- One capsule in the afternoon after school

- One capsule blend of rauwolfia vomitoria containing 25 mg mixed with adaptogenic herbs. Rauwolfia is an effective herb against anxiety and supports calmness.1

If a child was acting extremely agitated, she would give up to two capsules at one time, which would be equivalent to 800 mg of kava extract with 240 mg of kavalactone.

Within one week, the adoptive parent and teachers observed a dramatic shift in her behavior. Aggression subsided, she returned to school, and clonidine was successfully tapered—reducing the dose by approximately 25% daily over the course of one week.. Occasionally, two capsules (240 mg total) were needed in the morning during particularly dysregulated periods. Notably, at the onset of tantrum-like behaviors, administration of a kava capsule often rapidly mitigated escalation.

Over time, both siblings discontinued pharmaceutical medications entirely. Their PTSD and behavioral dysregulation were significantly improved, and they are now thriving in school, with symptoms managed solely through a natural protocol centered on kava.

Clinical Rationale: Kava and Pediatric Mental Health

Kava (Piper methysticum) is a traditional South Pacific root known for its anxiolytic, sedative, and mood-stabilizing effects. Its primary active compounds, kavalactones, modulate GABA-A receptor activity, inhibit norepinephrine reuptake, and influence voltage-gated ion channels—mechanisms that underpin its effectiveness in reducing anxiety and restlessness.2

Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of kava in managing generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and stress-related conditions in adults. A notable 2003 double-blind study published in Psychopharmacology found that 300 mg of kavalactones daily significantly improved anxiety scores compared to placebo, with minimal side effects.

While pediatric data remains limited, clinical observations like the one presented here highlight the potential of kava as an alternative to pharmaceutical interventions in selected cases of pediatric anxiety and trauma. Importantly, no side effects were observed in this case despite dosing that would be considered relatively high for a child, up to 240 mg of kavalactones per day.

Safety Considerations

Concerns over kava’s hepatotoxicity have been raised in the past, particularly in poorly regulated extracts or when combined with alcohol or hepatotoxic drugs. According to the World Health Organization, it is a rare occurrence usually due to drug interactions from excessive alcohol intake or immune-mediated idiosyncrasy.3

In this case, no liver abnormalities or adverse effects were observed over six months of use. No blood tests were performed for the six months; however, routine pediatric follow-ups showed no concern.

Conclusion

This case exemplifies the potential of evidence-informed botanical medicine to support complex mental health challenges in pediatric populations. The use of standardized kava extract provided rapid and sustained relief of PTSD and ODD symptoms in two children, allowing for reintegration into school and discontinuation of pharmaceutical treatment. As clinicians, we must remain open to the possibility that botanicals—when used with appropriate clinical judgment—can offer both safety and efficacy, even in challenging pediatric cases.

Dr. Friedman is a naturopathic physician and was adjunct instructor of endocrinology at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut. He is also the founder and director of the Annual Restorative Medicine Conference. Dr. Friedman is the author of the medical textbook Fundamentals of Naturopathic Endocrinology and co-author of Healing Diabetes. His research on the use of SR T3 has been published by the University Puerto Rico Medical School. He is the formulator and founder of the herbal supplement line Restorative Formulations.

References

- Charveron, M., Assié, M. B., Stenger, A., & Briley, M. (1984). Benzodiazepine agonist-type activity of raubasine, a Rauvolfia serpentina alkaloid. European Journal of Pharmacology, 106(2), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(84)90517-7

- Sarris, J., Stough, C., Bousman, C. A., Wahid, Z. T., Murray, G., Teschke, R., Savage, K. M., Dowell, A., Ng, C., Schweitzer, I., & Adams, L. (2013). Kava for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 33(5), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318297983a

- Teschke, R., Sarris, J., & Schweitzer, I. (2012). Kava hepatotoxicity in traditional and modern use: The presumed Pacific kava paradox hypothesis revisited. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 73(2), 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04070.x