A Prostate Cancer Discussion: Just What is “Aggression”?

Phranq D. Tamburri, NMD

Docere

You will never find the answer if you don’t understand the question.

(Proverb)

So, your 58-year-old patient presents to your office with a “PSA problem.” Perhaps you ask him specifically why he is here. He responds slightly cynically: “What do you mean, Doc? I understand this PSA test is high. So, do I have prostate cancer, or not?” Or, he might respond more generally with, “What is going on with my prostrate?!” [sig]

Initially, this seems to be a very normal interaction for both parties, especially to the clinician. However, to the integrative physician, this simple interchange obscures the bigger questions confronting you both: What are you really treating? What are your goals? What are the patient’s goals? Typically, they are not what the patient first believes he presents with. Do we want to lower the PSA? Is PSA even a problem? Is the PSA even linked to prostate cancer (CaP)? Or is it elevated for other reasons (infections, motorcycles, etc) even if CaP was diagnosed? Are we trying to reduce urination symptoms? Or maybe there are no symptoms. Are we trying to legally confirm CaP? Kill/destroy all CaP at all costs? Or just out-live it? If so, how many years are acceptable to the patient and his family? Refining these goals and having your patient soundly understand them is critical when tracking and treating the patient with CaP risk.

Living with Cancer – New Considerations

I have been honored that NDNR has asked for my contribution to the annual Men’s Health issue for a decade now. In each issue we have discussed prostate “current events,” ever-changing screening recommendations, and new testing options that sometimes change monthly! Prior issues have explored this exciting time for the prostate cancer medical field, with the emergence of genomic testing, new bio-tech conventional treatments, and lower-cost, high-tech imaging options – all converging with the expected demographic daily growth of Baby Boomers hitting the CaP-risk years. Complicating these issues is the Boomer generation’s demand to remain young and be sexually active well into their senior years. This is a significant attitude change from their parents’ ”Leave it to Beaver” generation. With this exploding market demand and exciting technological innovation, there has been constant change that makes it difficult for even the CaP specialist to stay current! As if that isn’t enough, there is one additional leg of profound change entering this medical specialty, one which has been heralded by both the naturopathic and integrative communities: a new relationship with cancer. The American Cancer Society changed their 40-year edict from “the war on cancer” to “living with cancer.” Whereas the market and technological changes have improved the overall detection of CaP, the latter conceptual change considerably shifts our focus to what to do about it!

What is the Patient Really Here For?

I wish to share with you the highlights of my opening dialogue with a new patient. Although they initially come to my office for color Doppler imaging and PSA kinetic calculations, I often reserve the first hour for this very discussion, if needed, sometimes before even opening the chart. This is a deliberate move to refocus the CaP discussion from external data to the internal personal. I want to focus on the patient’s priorities before we get sent down the “rabbit hole” of PSA values and biopsy scores.

Patient: I am here because my PSA is high. Do I have prostate cancer?

Doctor: Have you heard that we have cancer in us all the time?

Patient: Of course! Dr Oz even said that.

Doctor: Then why did you come here asking if you “have” prostate cancer? Of course you do!

Patient: OK, OK, point taken. But do I have a real prostate cancer?

Doctor: What would be an unreal prostate cancer?

Patient: OK, wise guy! I just want to know if it might be aggressive.

Doctor: What is “aggressive”? By what criteria?

Please understand that the point of this predictable narrative is never to play games with my patient, but rather to force him to confront the typical cliché contradiction with which most alternative-minded patients present. On the one hand, patients often restate what they’ve heard, ie, the claim that “we all have CaP”; on the other hand, they can become exceptionally anxious when told that they actually “have it.”

I sometimes follow up this point by asking the theoretical question, “If you ever received a ‘negative’ prostate biopsy, then wouldn’t you ask for your money back for not finding cancer?” Similarly, men claim they don’t trust an elevated PSA, yet after taking Serenoa repens, for example, they become encouraged when the PSA drops! As naturopathic physicians, we understand that psychology and proper framing of questions are critical components of our patient visits. This article will help answer the questions that are consistently presented during the CaP-patient visit.

“You Have CaP” – What This Means

As suggested above, if it is common knowledge that “we all have cancer in us all the time,” then what can we consider to be a “real” CaP? When speaking to my patients, I reframe “real” as “reproducible” or “significant” CaP. This refers to the potential that a CaP would be discovered at the same location and in relatively the same number of cores on a biopsy. In other words, if a patient was to undergo multiple biopsies (God forbid!), what are the chances that the same Gleason-grade cancer would be discovered at the same location? This conceptualization reduces the confusion and reality that numerous, random, CaP cells likely exist daily and could be picked up on biopsy and lead to unnecessary surgery.

Clinical indicators for a “significant” CaP include, but are not limited to, a positive digital rectal exam (DRE), overt lesions on imaging, worrisome PSA kinetics, and/or elevated molecular CaP testing results (PCA-3, TMPRSS2:ERG etc). Of course, the most definitive (and legally acceptable) indicator would be the biopsy itself. Although a biopsy is subject to misinterpretation, these criteria can be considered positive for a “significant” CaP if any of the following criteria are met: >3 cores positive, any core >30% CaP, or any core containing >Gleason 7(3+4). These criteria are currently used by urologists as a reasonable standard for distinguishing an “active surveillance” case from a surgical one.

It is interesting to note that the indirect evidence for the claim that we all have cancer involved CaP. It was supported by the spike of diagnosed CaP discovered only after the implementation of the PSA test followed by reflex biopsy. This finding forced the conclusion that generations of our ancestors most logically had prostate cancers that never killed them but which were never diagnosed prior to this often-unreliable test.

What is “Aggressiveness”? – Gleason Score

CaP “aggressiveness” means 1 thing only: Gleason Score following prostate TRUSP-guided biopsy. Period. End of story. “Aggression” does not mean what your patient may be thinking when he asks questions such as, “Is it bad?” or “Is it going to kill me soon?” or “Should I finish my bucket list now?”

Gleason essentially refers to the number of CaP cells undergoing division under high-powered field following biopsy. Put more technically, a pathologist microscopically examines the biopsy specimen for certain “Gleason” patterns and assigns a grade to the 2 most prominent ones. Lower grades are associated with small, closely-packed glands. As the grade increases, cells spread out and lose their glandular architecture. The pathologist then sums the pattern-number of the primary and secondary grades to obtain the final Gleason score. Essentially, it is a measure of differentiation wherein Gleason scores range from 2 to 10, with 2 representing the most well-differentiated tumors, and 10 representing the least-differentiated tumors. Higher Gleason score means less-differentiated cancers that do tend to divide more quickly. However, a key clinical pearl is that dividing quickly does not inherently mean that it will escape the gland sooner or at all! As suggested on the Gleason prognosis charts, even a high Gleason score does not predict that the patient will be deceased “next year,” even if detected late. I personally have tracked a few 12 out of 12 positive-core, Gleason-10 prostate cancer patients for 8+ years without any of them ever metastasizing. Certain patterns seem to quickly envelop the prostate without ever leaving it. Sometimes I sense that “aggressive” cancers are too intelligent to metastasize and kill their host! Cancer is like human beings – they have different “personalities.”

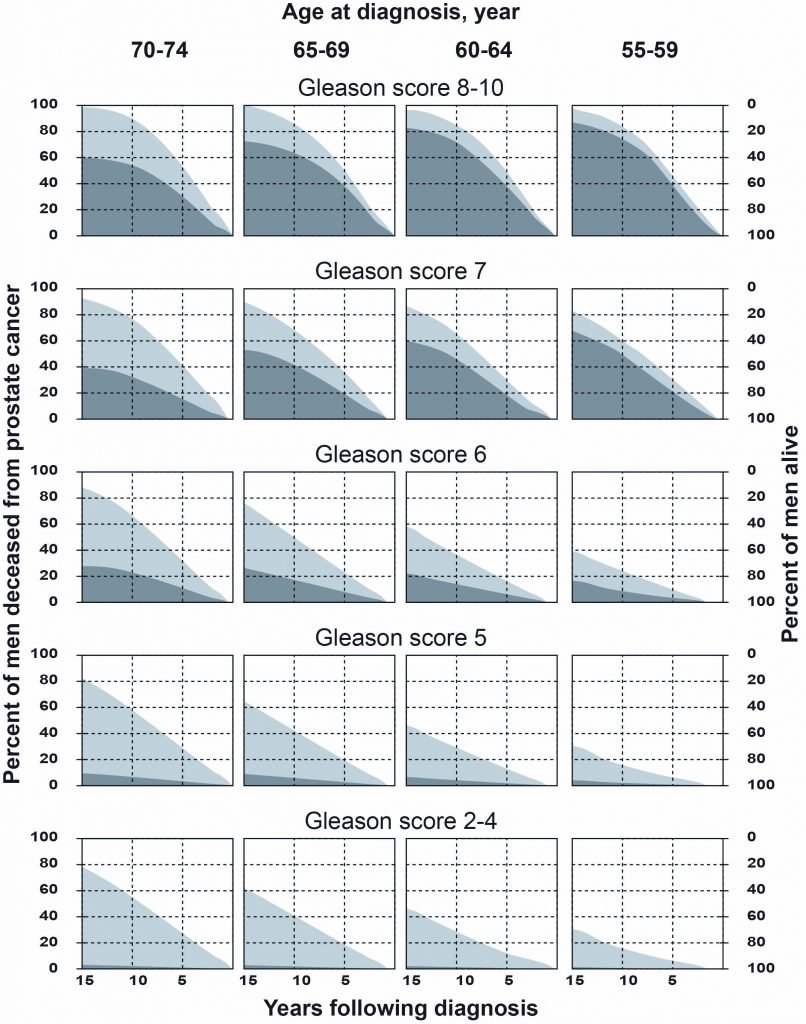

Figure 1. Gleason Score & CaP Mortality1

Survival (white lower band) and cumulative mortality due to prostate cancer (black upper band) and to other causes (light-gray middle band) 0-15 years after diagnosis, stratified by age at diagnosis and Gleason score. The CaP patients were managed conservatively, with either no treatment or treatment with hormonal therapy. (Adapted from Albertsen et al, 1998)1

Without treatment, it is critical for the patient to realize that even with a worst-case CaP diagnosed early (eg, PSA under 10, 3 cores positive, Gleason 10) he still has slightly less than a 50% chance of outliving the cancer for 15+ years! Yet, by far, the majority (>90%) of CaP found in men are only Gleason 6 and low 7.2 For a sexually-active 65-year-old man, this more optimistic perspective may instill the confidence to make the right decision for himself and his family.

Figure 2. 98.6% 5-Year Survival3

Based on data from SEER 18 2007-2013. Gray figures represent those who have died from prostate cancer. Green figures represent those who have survived 5 years or more.

Courtesy of the National Cancer Institute (https://www.cancer.gov)

Is a High PSA “Aggressive”?

The short answer is “no.” Assuming the elevated PSA is reflecting only primary CaP (not “red herrings” such as benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatitis, an autoimmune process, etc), then it is only reflecting the CaP’s activity and growth rate. Technically, it does not state “aggressiveness.” Can PSA help to assess “aggression”? If you define “aggression” as the point when CaP might metastasize, then the answer is “yes.”

Much has already been written about the poor reliability of PSA values in prior Men’s Health NDNR articles. However, here are a few pearls for assessing whether a PSA for a CaP could be indicating impending metastasis: The total PSA should not be over 10 ng/mL; the PSA (velocity curve) should not amount to 0.75 ng/mL/year for more than 2 consecutive years; and – most importantly – the PSA Density (total PSA/prostate volume) should not accelerate toward the extreme limit of 0.30. Keep in mind that these values are not the “official” and lower safe guidelines (PSA <4; PSA velocity <0.75ng/mL/yr; PSA Density <0.15). They are instead used, in my professional experience, as more realistic cutoffs when advising a fully consenting patient how far he can push his longevity and quality of life before a CaP most certainly will escape the prostate and metastasize. When one or more hit this upper limit, I must ensure the patient has informed consent that the CaP may have recently escaped or may be close to doing so.

Can Imaging (Color Doppler, TRUSP, MRI) Define “Aggressiveness”?

The answer is no. No amount of imaging can legally diagnose or define aggression of a CaP. After all, how could it? At best, it can show a hypoechoic lesion (black spot that is suspect for CaP) that can be photographed and measured. Besides giving a urologist a target to biopsy (if chosen), the image may help a patient come to terms with his situation when visualized. Furthermore, images can’t determine the genetic makeup or division rate of a prostate cancer.

So, why image at all? Imaging is extremely useful for determining other factors that can be used in assessing a CaP’s activity and the likelihood of it escaping the prostate. Imaging can demonstrate that the location of a suspect CaP is toward the capsule edge or by a seminal vesicle (a common escape port). It also can help diagnose other pathologies, such as BPH and prostatitis, that are known contributors to an elevated PSA. Color Doppler can determine how much blood flow activity is occurring, especially around CaP risk locations that suggest faster-growing CaP cells. Finally, and most importantly, image comparison studies can determine progression rates of these markers to determine if their chosen treatments are working and how much time they have before it may escape.

Case Study Comparison

Consider the following: Patient #1 has a small-lesion CaP – and a low Gleason 6 (3+3) – at the capsule edge, with mild extension (T3) near active blood vessels. Patient #2 has a similar-sized lesion, but this one is a much higher Gleason 10 (7+3) and nestled within the middle of a large prostate, away from large-vessel blood flow, as shown on color Doppler. Ask yourself, “Which patient has the more aggressive cancer?”

If we are speaking conventionally and legally, then Patient #2, with the Gleason 10, is obviously the far more (legally) aggressive case. However, if you want to know which cancer is more likely to kill the patient first, then it most likely is Patient #1. This is because he has a CaP at the very edge of the capsule, which is about to “fall out,” and which is actively fed (shown by color Doppler as increased blood flow).

Therefore, one can see that “aggressiveness” must be defined when used. This example clearly demonstrates that when it comes to using this charged term, the allopathic system and your anxious patient can often be having 2 very different conversations.

Quality of Life vs Longevity of Life

The choice between quality of life vs longevity of life is a critical and personal decision that the practitioner must have his or her patient answer in order to determine what is “aggressive” for their individual case. Most patients will initially respond that they “obviously want both.” However, they must pick. Sometimes, one must pressure the patient to confront this choice for his own well-being, the tranquility and acceptance of his family over his decision, and especially to ensure proper consent for the practitioner working with CaP cases that may become high-risk for metastasis.

Quality of Life (QOL) I define as the choice to retain bodily functions as normal as possible. Specifically, the concerns (if conventional CaP treatments are pursued) are erectile insufficiency, erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, sterility, and/or other permanent complications from conventional treatments. Does my patient have an active sex life? Does he have or even want a healthy libido? Was he widowed but he recently found the new “love of his life” with whom he wishes to enjoy as many quality years as possible? What is the realistic chance of BTB (Back to Baseline) functionality following a recommended surgery? If QOL is chosen, I will increase the risk tolerance and Active Surveillance threshold when determining his CaP “aggression.”

Longevity of Life (LOL) I obviously define as living as many years as possible. Will my patient be able to have a healthy relationship with his partner if sexual performance is severely curtailed? Is he a strongly family-oriented man who prefers to see his grandchildren get married? What is his current life-expectancy given his family history and current health history? If LOL is chosen, I will decrease the risk tolerance and Active Surveillance threshold when determining “aggression.”

”Aggression”: What Does it Really Mean to Your Patient?

It has been my experience that what your typically educated integrative patient means by “aggression” is this: “Do I have a prostate cancer that will kill me in the next 5-10 years?”

To answer this ultimate inquiry, we must first be clear about the following 2 points:

First, we must recall that CaP cannot begin to end your patient’s life (with the exception of physically blocking the urethra) until it escapes the prostate gland itself. Second, once a CaP escapes the gland, the typical patient has about 5 years before he even notices any physical change or pain. Although early lab work – prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), red blood cells (RBC), alkaline phosphatase, etc – will be clear to the physician when early-to-moderate-stage metastasis begins, the CaP has not likely progressed enough to bone and organ systems to be noticeable to them. After enough bodily systems are compromised, pain or other symptoms would typically drive the reluctant patient to their primary care physician for a work-up if they had not already done so.

At this point when physical symptoms appear, the CaP patient can typically now live another 5-10 years depending on Gleason score, organ system(s) involved, and what treatments are pursued. If the CaP is detected early (and most are when the PSA is under 10 ng/mL when undergoing routine physicals), the CaP is most likely not metastatic. Therefore, if a theoretical CaP escaped the capsule of your patient tomorrow, he will most likely live 10-15 years, with about half of that time involving no reduced QOL whatsoever. Figure 1 reinforces this qualitative time-table. So, to answer the patient’s question above, he will most likely be alive over the next decade as long as the CaP is still contained or has only recently escaped. Supporting evidence, beyond the high-risk PSA values stated earlier, includes the PAP, a sodium fluoride bone scan, circulating tumor Cell test (CTC), or the cutting edge C-11 acetate imaging that can detect cancer even in the surrounding soft tissue.

Aggression is an Amalgam Assessment

If you can relatively confirm to your in-office patient that the CaP has not escaped the capsule, then you can tell him he will likely be around for 5-10+ years. He is very happy. But then he follows up with his most liability-loaded last question: “So, if my CaP is not metastatic now, how long do I have until it is?” This question, I have determined, after many years seeing CaP patients, is the most refined meaning of what your patient really means when he asks if has an “aggressive” CaP. It is also the most difficult to answer, as it requires an amalgam of numerous factors, most described in this article.

In summary, this amalgam to answer your patient’s pragmatic interpretation of “aggression” includes 2 major components. One is the physical “bell-curve” of CaP linked markers and legal aggression that the prostate presents with (PSA kinetics, biopsy, color Doppler, ultrasound, molecular tests, DRE, etc), ie, the physical body. This bell-curve is coupled, or more accurately overlapped, with the other major component – the emotional and spiritual “bell-curve” that includes their education of CaP, family support, QOL vs LOL, anxiety level, financial resources, and overall informed consent regarding their risk.

Essentially, the closer these 2 bell-curves overlap, the easier the patient process and outcome will be, including expense, confidence, and anxiety level. The more the curves are staggered, the more testing, more money, and overall more anxiety on the part of the patient and family are usually involved. If this disparity is not understood or rectified, then the liability risk for the physician is also increased. Always challenge your patient to define the terms of both “aggression” and their specific goals from any treatment before you accept their case. Ultimately, communication/teaching is the key to reducing this amalgam disparity and is the foundation for the naturopathic physician – docere.

One Final Thought: A Different Perspective

Of course age, general health, sexuality, and life expectancy play large roles – factors that the naturopathic doctor should boldly approach with his CaP patient. When treating CaP, however, physicians are often much younger than their typical 65-year-old CaP patient with elevated PSA, and may not view their own mortality in as focused or grounded a way as their own patient.

A younger clinician may find “15 year” longevity something to aggressively fight with expensive, nest-egg-depleting therapies. This often is the modus operandi of the allopathic system. Yet your patient may consider a life expectancy of “only 10 years,” all things considered, as a positive. Through truly listening to my patients, I have found that advancing age does bring a different maturity and acceptance of one’s mortality. It truly does change the self-assessment game. It was difficult for me to appreciate and incorporate this into my earlier career assessments as a new, eager, and younger physician. I matured into my specialty when I recognized that this is where spirituality and sense of identity profoundly enter the “aggression” amalgam equation.

In summary, “true CaP aggression” is defined by a combination of advanced physical analysis of the gland, patient education with self-insightfulness, and by truly listening and even learning from your patient.

References:

- Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Gleason DF, Barry MJ. Competing risk analysis of men aged 55 to 74 years at diagnosis managed conservatively for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(11):975-980.

- Lepor H, Donin NM. Gleason 6 prostate cancer: serious malignancy or toothless lion? Oncology (Williston Park). 2014;28(1):16-22.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. Survival Statistics. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed September 5, 2017.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_alexmit’>alexmit / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Phranq D. Tamburri, NMD, is founder of Prostate Second Opinions, with an international patient clientele in Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Seattle. Dr Tamburri has been Professor of Urology at his alma mater, Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), for 16 years, and educates in all media forums for both patients and physicians on pragmatic approaches to prostate cancer. He has served as a board member of the Arizona Naturopathic Medical Association (AzNMA), co-hosts a 40,000-listener political/economic radio program, and loves desert rides on his green Kawai while blaring Tangerine Dream.

Phranq D. Tamburri, NMD, is founder of Prostate Second Opinions, with an international patient clientele in Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Seattle. Dr Tamburri has been Professor of Urology at his alma mater, Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), for 16 years, and educates in all media forums for both patients and physicians on pragmatic approaches to prostate cancer. He has served as a board member of the Arizona Naturopathic Medical Association (AzNMA), co-hosts a 40,000-listener political/economic radio program, and loves desert rides on his green Kawai while blaring Tangerine Dream.