Steve Rissman, ND

Is it best to let out one’s anger or to hold it in? Is counting to 10 better than saying what is on your mind? When it comes to anger expression, is less more? The right approach may seem simple to figure out for day-to-day social situations, but determining the better approach in therapeutic situations is more complex.

Anger expression, especially in the context of anger management, has become a significant topic of discussion and research. This question is of particular interest relative to anger management in men. While research has shown that holding anger in is not good, evidence also shows that excessive expression of anger is problematic. To better answer the question of whether to express or suppress anger, a closer examination is necessary.

Sigmund Freud is credited with the idea that anger builds up and must be released to keep oneself from exploding. According to his theory, anger catharsis acts like a pressure valve to “release steam” and to relieve buildup. This is probably the leading conceptualization of anger, but is it accurate?

In 1992, a small study1 published in the Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology found that holding in anger decreased gastric emptying, leading to dyspepsia. The suppression of anger—“attempts to resist, control, suppress, and hold in anger”1(p869)—was the dominant predictor of the presence and extent of more prolonged gastric emptying. Results of this study established a link between anger control and gastric pathology that led to dyspepsia. This supports Freud’s concept of anger.

A 2006 study2 looked at the relationship between optimism, anger expression, and natural killer cell cytotoxicity. This study focused on men with prostate cancer who were 45 years and older because older men are thought to demonstrate decreased ability to effectively express negative emotion. It was found that less anger suppression was associated with greater natural killer cell cytotoxicity.

These studies are representative of numerous investigations linking anger suppression to physical pathology. Although in the latter study holding anger in is found to be more useful, it still fits Freud’s image of anger building up pressure but in this case is a pressure cooker that kills cancer cells.

Indeed, much research suggests that keeping anger bottled up inside can have detrimental effects, which begs the question “What is the effect of ‘letting go of anger’?” A 2003 cohort study of 23 522 older male health professionals with low levels of anger expression concluded that “men with moderate levels of anger expression had a reduced risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction compared with those with lower levels of expression (relative risk: 0.56; 95% confidence interval: 0.32-0.97), controlling for coronary risk factors, health behaviors, use of psychotropic medication, employment status, and social integration.”3(p100) Furthermore, men with higher degree of anger expression had lower risk of stroke (ie, anger expression was inversely associated with risk of stroke). Thus, it would seem that expressing anger might cut one’s risk of heart attack and stroke by about half. Perhaps in the case of anger was Freud right?

Would greater expression of anger purge men of that vicious humor? (Are we not always trying to get men to emote more?) Anger may be a more complex biologic phenomenon than was explained by Freud.

In the 1980s and 1990s, anger therapy—the technique of screaming into a pillow or breaking glass plates to “release” anger—was popular. It may have felt good, possibly empowering someone who is not used to releasing such powerful emotion. Research since then has shown that forcing anger catharsis actually has negative effects, especially for people with explosive anger issues.

Brad Bushman at Iowa State University has been researching the issue for many years, and 2 of his studies4,5 on this topic summarize the key aspects. Bushman’s research suggests that the theory of anger catharsis may be wrong. Furthermore, his investigations have led him to conclude that catharsis behaviors show up in other ways with equal potential to cause harm.

In the 1999 study,5 Bushman and colleagues had 600 subjects hit a punching bag when thinking of someone who angered them (which increases ruminating thoughts) or when thinking about becoming physically fit (which is a distraction technique). At a follow-up interview, anger levels were assessed. Subjects who thought of someone who angered them (rumination group) were found to have higher levels of anger and were more aggressive than the distraction (control) group. As might be expected due to social norms, men had a stronger desire to hit the punching bag more times and harder than women. Bushman et al concluded that having rumination thoughts when venting created more anger and aggression, while having distraction thoughts when venting decreased overall anger and aggression, which contradicts the catharsis theory.

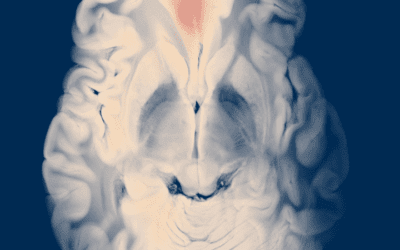

New understandings of the pathogenesis of anger support the conclusions by Bushman et al. Input from eyes, ears, and other sensory systems run to caudal aspects of the amygdala, while other pathways go to frontal cortex for interpretation. The pathways to frontal cortex require conscious thought, but the amygdala-bound pathways are reflexive, preparing the body for reaction to stimulus. This reflexive path triggers activation of the sympathetic nervous system by release of catecholamines that accelerate the heart beat, increase blood pressure and breath rate, coagulate the blood, and narrow one’s attention to the target. Other parts of the brain (ie, prefrontal cortex) are responsible for inhibiting or controlling the emotional response of the amygdala. Unfortunately, the neural connections from the cortex to the amygdala are not as well developed as the initial reflexive/upward pathway (ie, the path to the amygdala is dominant). Thus, when the amygdala creates a strong emotional response, as occurs with ruminating thoughts and anger catharsis, it is difficult to turn off. Larry J. Siever, professor of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, describes it this way:

The failure of “top-down” control systems in the prefrontal cortex to modulate aggressive acts that are triggered by anger provoking stimuli appears to play an important role. An imbalance between prefrontal regulatory influences and hyper-responsivity of the amygdala and other limbic regions involved in affective evaluation are implicated. Insufficient serotonergic facilitation of “top-down” control, excessive catecholaminergic stimulation, and subcortical imbalances of glutamatergic/gabaminergic systems as well as pathology in neuropeptide systems involved in the regulation of affiliative behavior may contribute to abnormalities in this circuitry.6(p429)

Perhaps much as one would work a muscle to make it stronger, anger catharsis unfortunately makes that neural pathway stronger. It reminds me of an Oriental saying: “You will not be punished for your anger; you will be punished by your anger.”

This is what stimulated my interest in men’s anger. Between the men I teach in my men’s health course and the men I work with in my practice, I noticed a considerable number whose lives are devastated by violent outbursts of anger, despite their having fairly gentle demeanors. On further investigation, I became aware of intermittent explosive disorder, an Axis I impulse disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) characterized by the following: (1) several discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses that result in serious assaultive acts or destruction of property, (2) grossly out of proportion to any precipitating psychosocial stressor, and (3) aggressive episodes are not better accounted for by another mental disorder and are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition.7(p670) Given that the prevalence rate for intermittent explosive disorder is 4% to 7%, this affects a large number of people, most of whom are men who could benefit by an understanding of healthy appropriate means of anger expression.

If anger catharsis increases anger and aggression, this has far-reaching implications. A subject of research by Bushman and Whitaker8 is the arena of violence and video games. Video games are a growing form of virtual entertainment that many claim helps them to vent their anger. However, new evidence reveals that video games are a form of anger catharsis that actually increases aggression, likely due to reinforcing the bottom-up neural pathway that goes unchecked.

Terrence, the Roman playwright, is credited with originating the injunction to seek “moderation in all things.” It would seem that his advice is valid to this day, especially in regard to anger. Modern research tells us that both suppression of anger and catharsis of excess anger can have detrimental health effects. Moderate anger expression appears to be the best path toward healthy management of anger. The next step will be to investigate therapies that support men in this endeavor.

Dr. Steve Rissman is a full-time faculty member in the Department of Health Professions at Metropolitan State College of Denver, teaching in the Integrative Therapeutic Practices program. He teaches clinical pathophysiology, holistic health, men’s health, homeopathy and several other classes. In addition, Dr. Rissman has a private practive in Denver and in recent years he has seen the need to focus his practice working specifically with men and boys, who all too often are not getting their health concerns addressed appropriately. Dr. Rissman has studied, taught and worked in the field of men’s health for over twenty years, and has committed his naturopathic medical practice to improving the lives of men and boys. He works with works with men/boys suffering with anxiety, compulsive behaviors, anger issues and a wide spectrum of physical pathologies such as heart disease, digestive disturbances, urological dysfunction, etc.

Dr. Steve Rissman is a full-time faculty member in the Department of Health Professions at Metropolitan State College of Denver, teaching in the Integrative Therapeutic Practices program. He teaches clinical pathophysiology, holistic health, men’s health, homeopathy and several other classes. In addition, Dr. Rissman has a private practive in Denver and in recent years he has seen the need to focus his practice working specifically with men and boys, who all too often are not getting their health concerns addressed appropriately. Dr. Rissman has studied, taught and worked in the field of men’s health for over twenty years, and has committed his naturopathic medical practice to improving the lives of men and boys. He works with works with men/boys suffering with anxiety, compulsive behaviors, anger issues and a wide spectrum of physical pathologies such as heart disease, digestive disturbances, urological dysfunction, etc.

Having grown up on a farm and spending a great deal of time in the outdoors, Dr. Rissman has a deeply rooted curiosity for the laws of nature, particularly the science of disease process. Consequently, he has an extraordinary ability to illicit the story of one’s unique disease process and to perceive what needs to be cured in each individual man/boy, using homeopathy, botanical medicines, therapeutic nutrition and other insightful methods intended to help lead men on the journey through the abyss of illness.

References

1. Bennett EJ, Kellow JE, Cowan H, et al. Suppression of anger and gastric emptying in patients with functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27(10):869-874.

2. Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Kinsinger D, et al. Anger suppression mediates the relationship between optimism and natural killer cell cytotoxicity in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(4):423-427.

3. Eng PM, Fitzmaurice G, Kubzansky LD, Rimm EB, Kawachi I. Anger expression and risk of stroke and coronary heart disease among male health professionals. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(1):100-110.

4. Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(6):724-731.

5. Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF, Stack AD. Catharsis, aggression, and persuasive influence: self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):367-376.

6. Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):429-442.

7. Kessler RC, Coccaro EF, Fava M, Jaeger S, Jin R, Walters E. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):669-678.

8. Bushman BJ, Whitaker JL. Like a magnet; catharsis beliefs attract angry people to violent video games. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(6):790-792.