Frasier Smith, ND

Abstract

Understanding how persistent plastic particles infiltrate human physiology—and what clinicians can do to help patients mitigate exposure and health impacts.

Micro- and nanoplastic exposure is now ubiquitous, with growing evidence linking these particles to inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, and potential cancer risk. This article reviews how these particles enter the body, their multisystem effects, and emerging naturopathic strategies for reducing patient burden.

Introduction

We live in a society that uses plastic for every conceivable use. Construction, transport, food storage, medical equipment, telecommunications, and clothing, to name just a few. Perhaps the archeologists of 3525 will refer to this as the “Plastocene era”! But what started with the development of crude ethylene extracts in the second half of the 19th century, and “Bakelite” in 1907, has mushroomed into a global machine that produces over 450 million tons of plastic a year.1 It has been known for a long time that plastic breaks down very slowly, that it is not very “biodegradable”, in the way that most papers and food waste is. But what has become starkly clear in the past few decades is that its breakdown actually yields environmentally and biologically persistent products that carry multiple adverse health effects and can increase our risk for many diseases. Moreover, the pervasive nature of plastics means that exposure to these particles is instant upon plastic use. These particles are known as microplastics and nanoplastics. These create serious risks for men’s health, which will be a focus of this article, but the health implications are serious for all people.

Definitions

The Environmental Protection Agency defines microplastics, or MPs, as plastic particles ranging in size from 5 millimeters (mm) to 1 nanometer (nm). In this sense, nanoplastics (NP) are a subset of MPs, the EPA considers NP to be smaller than 1 µm (1 micrometer or 1000 nm).2

Formation

MP are categorized by their formation as such, or as the product of breakdown of larger structures. Primary microplastics are those added to cosmetics or detergents, and many other products. Secondary microplastics are what becomes of plastic bags, food take-out containers, and the ubiquitous plastic water bottles, to name a few.3 They can also be classified by the sorts of polymers that they are composed of. Polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, and other materials being very common.3

Physiology

Micro and nano plastics (referred to as MNP in this article) are taken into the gastrointestinal tract, with nanoplastics being much more likely to be able to be absorbed through the gastrointestinal epithelium. Microplastics tend to embed on the gastrointestinal mucosa, where they can provoke inflammation.4 Nanoplastics can sometimes diffuse into the intestinal epithelial cell. Sometimes, they are taken up by the M (Microfold) cells.4 M cells are intestinal epithelium cells that uptake various small antigenic molecules and relay them to the immune system of the gut. This is a way of sampling the antigenic load of the gut – a kind of constant monitoring that can lead to rapid reaction to pathogens, but also to activation of Th3 – T regulatory activity. That is, it can be a way to develop tolerance. Nanoplastics can use this “side door” of the gut epithelium to enter the body. MNP associates with proteins in the gut, forming a “corona” around small peptides or protein molecules, which can also enhance their absorption (by association with amino acids).4

There are other routes, particularly the respiratory track. For example, a large amount of the plastic in automobile tires are aerosolized by interaction with the road (friction). Humans inhale this particulate plastic, and some can cross the respiratory mucosa. Even the seemly innocuous tea bag releases nano particles.5

Intravenous absorption of nano and microplastics happens every day. The tubing, bags, and syringes used for parenteral therapy release nanoplastics. The actual quantity is still under investigation and uses rather new techniques of quantification. One recent investigation estimated that:

Infusion solutions from PP bottles contain approximately 7500 particles/L. The particles ranged in size from 1 to 62 μm, with ∼90% of particles between 1 and 20 μm in size and ∼60% of the particles in the range 1 to 10 μm.6

To put this into context, the exposure from gut and air (and in some cases transdermally) far outweighs the amount of parenteral delivery of MNP, but the direct nature of this route and its usual salutary effects, makes it unique.

Health Risks

The health impacts of micro and nanoplastics are numerous. The scientific inquiry into these adverse effects are still of an experimental nature, that is, animal models or tissue systems are used to demonstrate the possible biological responses to the presence of plastics.

Nevertheless, early observations are being published in the scientific literature. For example, in 2024, Marfalla et. al, published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine about the presence of microplastics in atheromas. The researchers, who included vascular surgeons, analyzed the atheromatous plaques from the carotid artery and found that those patients who had microplastics in their plaques had a high risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death at 34 months follow up.7 Tonsils have been found to aggregate these plastics, and Dr. Kara Meister at Stanford has an ongoing study examining children’s tonsils. The consensus seems to be that with thousands of compounds involved in making many kinds of plastics, and so much exposure, the science is new in this area of plastic-human interaction.8 The role of MNP in the prostate is not entirely clear, but very recent research has found elevated MNP in prostate tumors.9

Using a broader range of experimentation, the biological effects of micro and nanoplastics are very concerning. While not surprising in principle, the extent and the many modes of biological dysfunction that these substances cause is stunning.

At the cellular level, MNP can penetrate cell membranes, often in association with proteins. Forming what is called a soft or hard “corona” – hard corona structures are proteins with MP deeply embedded in their structure and “soft” those with MP loosely attached to their outer structure. MNP can enter the cell or may stay in the cell membrane. Those that persist in the membrane will alter the fluidity and function of the cell membrane, which in experimental models can even cause cell death. 4,10

MNP can cause trouble with organelles. Mitochondria exposed to MNP can display impaired mitophagy (autophagy of the mitochondria), which decreases the housekeeping functions to remove damaged proteins. They might also show increased oxidative stress, which can seriously damage mitochondria. The endoplasmic reticulum can also suffer from oxidative overload due to MP and can start to turn out more misfolded and useless proteins.(4)

MNP can trigger the innate immune system leading to increased inflammation. This is not surprising since they are a foreign body. This inflammation can increase risk of other diseases and there is a theoretical increase in cancer risk. This could be due to more oxidative stress and potential mutations to cells. But more importantly, inflammation in a tumor microenvironment, in any instance where cells becomes truly neoplastic, can aid the cancer in its various strategies to overtake the body’s defenses. This leads to more inflammation, desmoplasia (increase of stiff, crosslinked collagen around the tumor) and ultimate breakdown of the extracellular matrix which contributes to tumor spread. In animal models (such as mouse, and zebrafish), cancers could be induced with MP; the implication for humans requires much further study, albeit with increasing concern for the trajectory of cancer development in humans with massive total and cumulative MP exposure.4

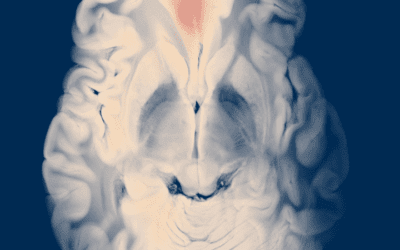

MNP can cross the blood brain barrier. The coronas described above can cross the endothelial junctions near the brain. They can increase oxidative stress, trigger neuroinflammation, and reduce acetylcholine function (which can impact mood and memory). 10,11

These examples are meant to illustrate the scope of impact of MNP and the specific ways in which they injure the body. A more extensive inventory of the body-wise effects of MNP would easily take up a series of articles.

Avoidance and Mitigation

For a long time, naturopathic physicians have been advising patients to not cook or even store their food in plastic. It is clear that avoidance is difficult with the breakdown products being so ubiquitous. Even a plastic water bottle (slowly being replaced it seems with reusables but still very popular) can deliver a lot of MNP. A study published in 2024 showed that one plastic bottle of water had 100,000 particles of plastic in 1 litre of water. 12,13 To compound matters, filtration systems, like reverse osmosis, which can remove many toxins, including MNP, can themselves start to release MNP if it is not replaced on schedule.

New research into herbal medicines shows MNP binding, often remarkably, by plant extracts. A lot of this research is currently done on standing water samples. The ability of these extracts to bind MNP in the body requires more research, and that also raises the question of how quickly the body can move to eliminate such complexes.

Srinivasan et all (2025) showed that a Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) and Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) combination was able to remove 77% of plastic particles in a freshwater sample.14 The dietary supplement Chlorella, an extract of green algae (such as Chlorella vulgaris) can remove microplastics from water, so perhaps, in the gut, it could block some absorption.15

Naturopathic physicians are adept at supporting detoxification and elimination in the liver and through the so-called “emmunctories” (organs and channels of elimination). The MNP load our patients face makes this work more needed than ever. While the plasticizers (additives) to plastic such as Bisphenol A, are eliminated in sweat (which makes sauna and other hydrotherapies indicated), the ability to sweat out actual nanoplastics is not clear.

Any trapped toxin, especially a structurally embedded molecule such as MNP, must pass through the extracellular matrix in order to find its way to an eliminative channel. Support for the extracellular matrix via plant polyphenols and nutritional factors such as vitamin C, seem reasonable. Moreover, a major eliminative pathway for the extracellular matrix is the adjacent lymphatics; therefore, lymph draining therapies such as bodywork, herbs, and physiological therapeutics could be helpful.16

New medical treatments are under investigation. Extracorporeal therapeutic apheresis is one such approach. It separates plasma from the rest of blood and uses filters to trap the MNP. This temporary removal and literal filtration of blood is a higher force intervention than using plant extracts, but we may yet need such treatment for some patients given the depth of penetration of MNP, provided that it proves to be effective, and of course, safe.17

Conclusion

Looking back in history, it can seem incredible that people dumped their sewage into the street and their drinking water. We only have to look at cities in the 19th century to see this. Much further back in time, the Romans created amazing aqueducts for fresh water and for the nicer neighborhoods, even sewer systems (cloaca). But they mingled in public baths, spreading microbiota amongst the populace. It is easy to look at these examples and decry them as ignorant of science, and even a bit stupid. But turning our critique on our own society, we are similarly awash in microscopic entities that can cause disease. In this case, they are of our own making, and they are everywhere. As the science progresses – and the societal consciousness to take our reckless use of plastic more seriously emerges – naturopathic physicians can play an important role in helping patients predict, avoid, and to some degree expunge these compounds. In the meantime, we do this work everyday with patients: reducing the levels of inflammation, restoring and supporting pathways of detoxification, cultivating a diverse and healthy microbiome, and more, will help them face this challenge.

Fraser Smith, MATD, ND, is a licensed naturopathic physician, educator, and author with over two decades of experience in integrative and naturopathic medicine. He serves as Assistant Dean of Naturopathic Medicine and Associate Professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences at National University of Health Sciences, where he helped launch and continues to lead the naturopathic medicine program. He is widely recognized for his work in evidence-informed naturopathic practice, clinical education, and the development of rigorous academic standards, and has served as core faculty at multiple naturopathic medical institutions, teaching clinical sciences, physical diagnosis, and professional practice while mentoring future physicians.

References

1.Ritchie H, Roser M, Samborska V. Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data. Published 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

2.Microplastics Research | US EPA. US EPA. Published April 22, 2022. http://www.epa.gov/water-research/microplastics-research

3.Osman AI, Hosny M, Eltaweil AS, et al. Microplastic sources, formation, Toxicity and remediation: a Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters. 2023;21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01593-3

4.Lai H, Liu X, Qu M. Nanoplastics and Human Health: Hazard Identification and Biointerface. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(8):1298. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12081298

5.Hernandez LM, Xu EG, Larsson HCE, Tahara R, Maisuria VB, Tufenkji N. Plastic Teabags Release Billions of Microparticles and Nanoparticles into Tea. Environmental Science & Technology. 2019;53(21):12300-12310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b02540

6.Huang T, Liu Y, Wang L, et al. MPs Entering Human Circulation through Infusions: A Significant Pathway and Health Concern. Environment & Health. Published online February 14, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/envhealth.4c00210

7.Raffaele Marfella, Prattichizzo F, Celestino Sardu, et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2024;390(10):900-910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2309822

8.Ekvall MT, Naidu S, Lundqvist M, Cedervall T, Värendh M. The forgotten tonsils—does the immune active organ absorb nanoplastics? Frontiers in Nanotechnology. 2022;4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2022.923634

9.Demirelli E, Tepe Y, Oğuz U, et al. The first reported values of microplastics in prostate. BMC Urology. 2024;24(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-024-01495-8

10. Kopatz V, Wen K, Tibor Kovács, et al. Micro- and Nanoplastics Breach the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB): Biomolecular Corona’s Role Revealed. Nanomaterials. 2023;13(8):1404-1404. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13081404

11.Prüst M, Meijer J, Westerink RHS. The plastic brain: neurotoxicity of micro- and nanoplastics. Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 2020;17(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-020-00358-y

12.Qian N, Gao X, Lang X, et al. Rapid single-particle chemical imaging of nanoplastics by SRS microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2024;121(3):e2300582121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300582121

13.Nanoplastics Are All Around (and Inside) Us | Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Columbia.edu. Published May 8, 2025. https://lamont.columbia.edu/news/nanoplastics-are-all-around-and-inside-us

14.Srinivasan R, Rajita Bhuju, Chraibi V, et al. Fenugreek and Okra Polymers as Treatment Agents for the Removal of Microplastics from Water Sources. ACS Omega. Published online April 10, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c07476

15.Esmaeili Nasrabadi A, Eydi M, Bonyadi Z. Utilizing Chlorella vulgaris algae as an eco-friendly coagulant for efficient removal of polyethylene microplastics from aquatic environments. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e22338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22338

16.Smith F. The Extracellular Matrix in Health and Disease. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-94465-9

17.Bornstein SR, Gruber T, Danai Katsere, et al. Therapeutic apheresis: A promising method to remove microplastics? Brain medicine : 2025;1(3):52-53. doi:https://doi.org/10.61373/bm025l.0056

Author Bio:

Optional – image from wikimedia commons

<a title=”Oregon State University, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons” href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Microplastic.jpg”><img width=”512″ alt=”Microplastic” src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Microplastic.jpg/512px-Microplastic.jpg?20201216153311“></a>