COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2: Diagnostic Testing Overview

Docere

David M. Brady, ND, DC, CCN, DACBN, IFMCP, FACN

There is a lot of conversation and controversy surrounding the issue of laboratory testing as it pertains to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2. This has generated an unfortunate amount of media misreporting and confusion on the part of the lay public and healthcare providers alike. In this brief article, I will attempt to provide some clarification regarding this topic. By intention, this is not a highly technical article written to be submitted to a laboratory science or immunology journal, but simply a high-level overview of the testing options, including their strengths and limitations and, most importantly, their clinical utility.

Diagnostic Testing for COVID-19

COVID-19 RT-PCR Molecular Test

The diagnostic test for detecting the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is a RT-PCR molecular test (RT-PCR stands for “real-time polymerase chain reaction”). The assay is for use on samples collected via nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs, throat swabs, bronchoalveolar lavages, and bronchial washings.1-2 The COVID-19 assay test is available now from various high-complexity laboratories – mainly academic and large hospital pathology labs, large national commercial labs, and a handful of smaller, independent commercial labs that are technologically capable and have submitted proper validations of their testing to the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). You can find a list of labs here: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/faqs-diagnostic-testing-sars-cov-2#offeringtests.3

Figure 1. Sample Lab Report of RT-PCR Test

It is important, however, to realize that not all of these tests are the same. Laboratories were allowed under the EUA to develop their own testing methodologies, based on minimum acceptable guidelines issued by FDA, and to submit their own validations to the agency. For example, labs have specific sequencing equipment and will use different reagents and methods to perform the test according to the particular equipment they have. Some of the tests are based on preconfigured test kits manufactured to only work on certain laboratory analysis platforms, sort of analogous to needing to have the correct ink jet printer cartridge for it to work in a specific brand and model of printer. Another varying factor is the number and type of molecular targets used to accurately identify the virus in a sample. FDA issued guidance stating that an appropriately validated single viral target SARS-CoV-2 assay could provide acceptable performance. However, the initial test supplied by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) used 2 molecular targets, and it did not perform well at properly identifying those targets, as has been reported widely in the media. Under the EUA, labs were permitted to develop their own targets and methods, but had to submit validation data to FDA showing that the test performed adequately before being allowed to commercialize the test.

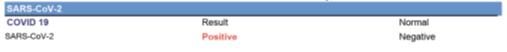

For example, at Diagnostic Solutions Lab (DSL), our team of molecular laboratory scientists chose to target 4 specific molecular targets novel to SARS-CoV-2 in order to identify the pathogen with greater sensitivity and specificity. These include the N1 and N3 nucleocapsid protein targets (which were also used in the original CDC assay), plus a novel spike (S) protein and envelope (E) protein (see Figure 1). In this way, it is almost impossible to miss the virus as long as the sample is collected properly and there is adequate viral load on the swab or in the sample. Sample collection is the weakest link in the chain in regard to this type of testing, and false negatives have been primarily attributable to faulty sample collection by the healthcare practitioner and/or low viral load in the specific areas the sample was derived from, as opposed to the molecular laboratory method.4 However, there is a distinction between COVID-19 molecular tests that use a PCR step to amplify DNA in the sample and those that do not. There are several so-called “rapid” testing platforms out there, offered by very large biotech companies, which get a lot of media attention; however, these systems are “rapid” because they lack this PCR step, As a result, they are much more dependent on having a substantially higher viral load on the swab to be “positive.” For example, these non-PCR systems generally require a viral load of “e5” or higher, whereas the PCR molecular test methods are often capable of detecting the virus at “e3,” or even “e2,” levels of viral load, which is exponentially better sensitivity. These non-PCR test methods have been criticized by critical care clinicians for what appear to be “false negatives,” as patients whose rapid tests come back “negative” often have convincing clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and are located in a hot zone of disease activity.

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Molecular Targets

COVID-19 Saliva Test

Just prior to completion of this article, a new saliva sample test was also approved by FDA through the EUA for COVID-19. While this test is getting a lot of media attention, and a saliva sample holds a certain appeal compared to a NP swab (it is much more comfortable for the patient and is safer for the healthcare provider), there are significant drawbacks not reported in the coverage.

Like rapid tests, the saliva test is more applicable for use in testing subjects who are significantly ill – such as patients in a hospital setting – and/or healthcare workers in acute care facilities who may be exposed continuously to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This is because a significant viral load threshold must be met to have enough viable viral particles to detect SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. It is extremely challenging to get the required volume of saliva and to concentrate it sufficiently to yield good low-end sensitivity on this type of sample. In summary, both the rapid tests and saliva tests are better suited for point-of-care situations dealing with significantly clinically ill subjects, and while “positives” can be relied upon with confidence, these tests are prone to false-negatives due to low-end viral load sensitivity; false-negatives are frequently being reported by frontline healthcare professionals.

Summary for RT-PCT Testing

Through laboratory experience to date, here are the preferred samples (in terms of sensitivity and specificity) on which to perform COVID-19 RT-PCR testing, listed in descending order:

- bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial washings

- nasopharyngeal (NP) swab

- oropharyngeal (OP) swab

- nasal swab

- saliva

Diagnostic Testing for Antibodies

SARS-CoV-2 Blood Antibody Test

This is a blood test for antibodies to the virus that causes COVID-19. To be clear, the virus is named SARS-CoV-2, not COVID-19; the clinical disease is named COVID-19. Antibodies are produced by the immune system as part of its response to fighting foreign invaders such as viruses. This test will provide information about whether the subject’s immune system has responded to an exposure to SARS-CoV-2. The results will therefore help to illuminate whether the subject has been exposed to the virus and, if so, whether that individual might therefore have some level of immunity. This test can be used to screen both symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. This is extremely important, as recent studies suggest a high percentage of people who carry the virus show no clinical symptoms.

It is important to understand, though, that an antibody test cannot independently tell you whether a subject has COVID-19. According to FDA, since COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory disease, the formal diagnostic test is performed by swabbing the nose or mouth, not by running a blood test. For subjects who feel sick with any symptoms of COVID-19, such as fever, body aches, chills, fatigue, new or worsening cough, or shortness of breath, the treating doctor should collect a NP swab and have a RT-PCR test performed to confirm the diagnosis.

The antibody test is designed to screen the subject’s blood for 2 types of antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These antibodies are known as IgM and IgG. You will generally see a “positive/detected” or “negative/not detected” result for IgM and IgG antibodies to the virus on the test report. Note that results may come back in a way that is hard to interpret; in this case, results are generally reported as “equivocal.” This means that the sample showed high enough titers to not be definitively negative, yet not quite high enough to be definitively positive.5

What Positive Serology Results Mean

- Positive or “Detected” IgM Results: A positive IgM result suggests that the subject has been recently exposed to this virus and may be fighting an active infection. They may be contagious even if they do not have any symptoms. Public health authorities have stated that people without symptoms can still pass this virus to others. IgM antibodies typically begin to increase in the blood 5 days after exposure to the virus, while the rate at which they return to normal is not fully understood in SARS-CoV-2 and may also vary from subject to subject.

- Positive or “Detected” IgG Results: A positive IgG result suggests that the subject has had previous exposure to the virus and may have immunity against future exposure. The level of immunity and the length of time it lasts are not yet fully known, but researchers are actively working to understand this. Infection and recovery should allow for at least 18 months of immunity, possibly much longer, and possibly decades. While SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, we have to assume for now that it will behave similarly to other coronaviruses, and most other viruses, for that matter. However, time and retrospective study will confirm or disprove this. In the meantime, subjects with positive, or detected, IgG should continue to follow guidance from the CDC and other public health officials, as well as follow all government orders, to help protect themselves and their family from the virus, and they should continue to follow all guidelines regarding social distancing, hand hygiene, sanitation, etc.

The basic way that IgG antibodies work is that they increase after IgM antibodies are present. IgM antibodies are essentially the initial special-forces fighters that set up the initial beach head, while IgG antibodies are the long-term ground troops that serve as the occupying force. The immune system makes IgG from IgM via seroconversion over time after initial pathogen exposure, so subjects may show both positive IgM and IgG at earlier stages, or negative IgM and positive IgG as time goes by.

What Negative Serology Results Mean

- Negative or “Not Detected” IgM Results: A negative IgM result suggests that the subject has not been exposed to this virus recently and that their immune system is not showing evidence of fighting an active infection. A negative IgM result along with a positive IgG result probably means that the subject had an infection in the past and likely has at least some level of immunity.

- Negative or “Not Detected” IgG Results: A negative IgG result suggests that the subject has not been exposed to this virus and does not have any level of immunity to it. The exception to this is when they have a positive IgM, but not yet a positive IgG. In this case, it may be too early in the subject’s exposure to the virus for their body to have made any IgG through seroconversion of IgM.

Figure 3. Lab Report of Antibody Test

SARS-CoV-2 “Rapid Blood-Spot” Test

Another big problem that very few people in the media seem to understand is that the “rapid blood-spot” collection antibody tests – now being commonly referenced in news stories and being marketed as at-home tests – are not quantitative. In other words, they are only qualitative (positive or negative), and you need a very large amount of antibodies to show a “positive” on these tests. This type of testing should be reserved for those with significant clinical symptoms for at least 12-24 hours, as they will show a “positive,” generally for IgM, or for both IgG and IgM antibodies, consistent with a significant active infection. Therefore, this type of antibody test method is really more suited to actual “diagnosis confirmation” of active COVID-19 in a clinical setting, such as a hospital ICU, and can be used in parallel with NP swab (RT-PCR) testing to confirm a clinical diagnosis of COVID-19.

For learned or acquired immunity assessment, these blood-spot tests do not work well because they can’t quantitate the titers specifically enough to determine the slightly-to-moderately-elevated antibodies required to see patterns of post-infection acquired immunity (ie, low-elevations of IgG being maintained, and a return to no IgM). Put another way, the rapid blood-spot tests need high viral load and subsequent significant antibody production to generate a “positive” result, but they can’t sufficiently discern the lower levels necessary for assessing long-term immunity. Unfortunately, this requires a blood draw in an SST tube, and a spin-down, in order to acquire the serum sample needed for more specific quantitative antibody testing.

A final comment on antibody testing involves quality of the assay itself. There are many smaller “niche” labs that have seen their standard testing volume drop precipitously during this crisis, and which lack the molecular talent to have even attempted to develop and validate a RT-PCR diagnostic COVID-19 test. However, possibly to help in the crisis and/or possibly to start sample volume and revenue coming in the door again, many of these small labs have jumped into the antibody testing arena with little to no experience in this type of testing. The testing does not require the individual lab to develop the test from scratch, but simply requires them to obtain pre-made ELISA test kits for this purpose. However, lacking the strong supply chain and vendor relationships required to access and obtain the high-quality prepared test kits manufactured in the United States and Germany – which are in limited supply – many have had to resort to much lower-quality, Chinese-made test kits with a somewhat less-than-stellar track record. I would encourage the clinician to ask such questions of the labs you are considering ordering antibody testing from, in order to assure the validity and quality of the results data you ultimately receive in return. The SARS-CoV-2 ELISA IgG and IgM kit assay being used in the DSL lab is US-made and has been approved by FDA under the EUA.

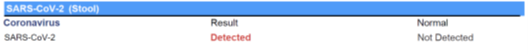

SARS-CoV-2 Stool Test

The SARS-CoV-2 stool test also uses RT-PCR technology to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in stool. Coronavirus stool tests can help practitioners screen for SARS-CoV-2 as well as to monitor and surveil patients who have tested positive for the disease. Research from around the world indicates that as many as 50% of patients who are positive for SARS-CoV-2 experience gastrointestinal complaints, and that those who do have poorer outcomes.6 Furthermore, evidence suggests SARS-CoV-2 is detectable in stool and that its presence in stool may last for up to 5 weeks after clearance from the respiratory tract and resolution of symptoms.

A recent article published in Lancet states,

Our data suggest the possibility of extended duration of viral shedding in faeces for nearly 5 weeks after the patients’ respiratory samples tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Although knowledge about the viability of SARS-CoV-2 is limited, the virus could remain viable in the environment for days, which could lead to faecal–oral transmission, as seen with severe acute respiratory virus CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV. Therefore, routine stool sample testing with real-time RT-PCR is highly recommended after the clearance of viral RNA in a patient’s respiratory samples. Strict precautions to prevent transmission should be taken for patients who are in hospital or self-quarantined if their faecal samples test positive. (Wu Y et al, 2020)7

For practitioners who are surveilling positively-identified SARS-CoV-2 patients, coronavirus stool testing offers an important adjunct test to the NP swab. The stool test does not confirm clinical COVID-19, but it does confirm exposure to and infection with SARS-CoV-2. In other words, the SARS-CoV-2 stool analysis is not diagnostic of COVID-19. Again, according to FDA, COVID-19 disease can only be diagnosed with positive SARS-CoV-2 results on a respiratory sample. Some individuals with fecal SARS-CoV-2 go on to develop clinical COVID-19, but many do not, and post-exposure sequela varies from asymptomatic to rapid progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. A positive stool test means that the subject has been exposed and infected with the virus and – even if asymptomatic – is shedding virus in stool; such an individual should be compulsive about hand washing and other sanitary measures, especially post-defecation. It also means they likely have post-exposure immunity. This kind of finding, combined with quantitative IgG/IgM antibody testing, may allow clinicians to strategically determine who may be able to safely return to work. We are still learning as this develops, and many labs, including DSL, are working with FDA and CDC on suggested clinical guidelines based on what lessons emerge from testing larger portions of the population.

Figure 4. SARS-CoV-2 Stool Test

Clinical Integration

It is important for the clinician to understand the clinical application and integration of testing results for the various types of testing options related to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Again, allow me to stress that, per FDA guidelines, a diagnosis of COVID-19 can only be arrived at when the patient is exhibiting the respiratory symptoms correlated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (ie, cough, sneezing, rhinitis, shortness of breath, elevated temperature) and is also positive on molecular testing of a respiratory sample, preferably with RT-PCR on an NP swab or lung sample (bronchoalveolar lavage or bronchial washing). Additional information supporting this diagnosis can be obtained with “positive” or “detected” IgM antibodies for SARS-CoV-2, preferably with serum sampling.8 Studies indicate that the positive detection rate may increase to 98.6% with combined IgM and RT-PCR testing, as compared with RT-PCR alone (51.9%).9

A positive COVID-19 diagnostic test result and/or a “positive” or “detected” IgM antibody to SARS-CoV-2 should constitute reasonable grounds to implement immediate home isolation and, in this author’s opinion, should be reported to local public health authorities; I would also stress that all recommended protocols for that jurisdiction should be followed.* While definitive reporting policy has been established for positive PCR testing on respiratory samples, the landscape is much murkier when it involves positive IgM results; one would expect the regulatory policy to start to catch up over time in this regard. “Positive” or “detected” IgG antibodies, in the absence of IgM, indicates previous exposure and no active infection; therefore, there is no reason to quarantine the subject unless symptoms occur.

A positive SARS-CoV-2 stool test may occur in a person with or without active COVID-19. If the subject exhibits signs and symptoms of COVID-19, he or she should be managed as such. However, if no symptoms are present, and in the absence of a positive diagnostic test (ie, RT-PCR on a respiratory sample), the subject should be considered as having been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 but also as harboring the virus in the gastrointestinal tract and potentially able to spread the virus through oral-fecal contamination. While these subjects are likely not transmitting the virus through the traditional respiratory routes, they must be compulsive about hand washing, especially after using the bathroom, to avoid this type of spread.

*Please note that public health policy and recommendations to healthcare providers varies from state to state, and even county to county, so please remain informed about these guidelines and responsibilities for licensed healthcare providers in your area.

Closing Thoughts

I hope this summary of available testing related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 has been helpful, adding to what you likely already know. It was intentionally kept simple and to the point, as the nature of some of the questions that I have been getting on many of the online practitioner forums suggested that this information may be useful and necessary. It is my hope that, with this review, practitioners will have a better understanding of the various testing options and their clinical utility, as we all learn our way through this new landscape.

In closing, I want to just acknowledge that these have certainly been really surreal times for all of us. For instance, I could not have imagined just a month ago that I would soon be getting calls from critical care physicians from New York City hospital ICUs asking about proper protocols for high-dose IV vitamin C to provide to patients, or that I would be seeing very conventional hospitals in the United States starting trials on administering medical ozone treatments, or that I would be witnessing the rapid discovery of previously unnoticed supportive scientific literature on natural substances (ie, botanicals, plant polyphenols, melatonin, etc) – and their ability to favorably modulate immune responses and disrupt viral replication and cell penetration – by those who were previously entirely uninterested, and even hostile, to natural medicine. I also never thought I would see the level to which the general public has sought to obtain nutritional supplements and nutraceutical products during this pandemic, effectively turning back to natural medicine when there was no magic pharmaceutical bullet to save them in their time of need. In my almost-30 years in the fields of integrative, functional and naturopathic medicine, I have never been prouder of our collective professions and what we have to offer to the healthcare system, if only we were utilized more fully. I have seen colleagues of mine step up and uncover amazing data and information on potential therapeutic approaches to help patients have a better chance of successfully surviving this infectious outbreak should they be exposed, and I firmly believe that all of the increased utilization of what have been known as complementary and natural therapies has kept countless people out of acute medical care facilities and has saved lives.

I also wanted to acknowledge the scientific team at Diagnostic Solutions Lab (DSL) for basically pivoting on a dime from their usual work and diving head-first into the rapid development of various types of COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 testing platforms when their nation, and the world, called. To think that a comparatively small, high-complexity, independent laboratory that predominantly serves the integrative and functional medicine market could be one of the very first laboratories in the United States to submit FDA validation data and begin the desperately needed COVID-19 testing for some of the largest and most prestigious hospital systems in the country, when even their own institutional-based pathology labs could not, is just mind boggling. To be one of the first 30 labs in the country on the FDA list of laboratories for COVID-19 testing, when the others included the 2 massive national reference labs and a short list of very large prestigious academic medical institution-affiliated laboratories, is impressive, to say the least. And to offer much faster turn-around-time to critical care clinicians in desperate need of answers for their patients is also laudable and likely saved lives. So, to all of DSL’s molecular and laboratory diagnostic scientists (PhDs), clinical doctors (MDs and NDs), the front line clinical laboratory, and the back-end support staff who have not slept much in well over a month, I salute you. You are real heroes, and you have done integrative, functional, and naturopathic medicine proud. Many people, including healthcare and government regulators, have noticed.

References:

- Tang YW, Schmitz JE, Persing DH, Stratton CW. The Laboratory Diagnosis of COVID-19 Infection: Current Issues and Challenges. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Apr 3. pii: JCM.00512-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00512-20. [Epub ahead of print]

- Haveri A, Smura T, Kuivanen S, et al. Serological and molecular findings during SARS-CoV-2 infection: the first case study in Finland, January to February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020 Mar;25(11). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.11.2000266.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FAQs on Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Last updated April 17, 2020. FDA Web site. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/faqs-diagnostic-testing-sars-cov-2#offeringtests. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- Leung DT, Tam FC, Ma CH, et al. Antibody response of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) targets the viral nucleocapsid. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(2): 379-386.

- Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 28. pii: ciaa344. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [Epub ahead of print]

- Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar 3. pii: S0016-5085(20)30282-1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [Epub ahead of print]

- Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):434-435.

- Xiao DAT, Gao DC, Zhang DS. Profile of Specific Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2: The First Report. J Infect. 2020 Mar 21. pii: S0163-4453(20)30138-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.012. [Epub ahead of print]

- Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling Early Humoral Response to Diagnose Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 21. pii: ciaa310. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310. [Epub ahead of print]

David M. Brady, ND, DC, CCN, DACBN, IFMCP, FACN, has almost 30 years of experience as an integrative practitioner and 25+ years in health sciences academia. He is a licensed naturopathic physician in CT and VT, is board-certified in functional medicine and clinical nutrition, and is a fellow of the American College of Nutrition. Dr Brady is CMO of Diagnostic Solutions Labs, LLC, and Designs for Health, Inc. He is the former vice president for Health Sciences and long-time director of the Human Nutrition Institute at UB in CT, where he still serves as an associate professor of Clinical Sciences. Dr Brady is a frequent speaker at prestigious conferences and is in clinical practice at Whole Body Medicine, in Fairfield, CT.