The Missing Link

Jennifer Gibbons, ND

Osemekhian Okojie, ND Cand

As naturopathic physicians, much of our patient education revolves around the importance of a healthy diet, better relationships, and reducing unhealthy stress. Equally as important, but often overlooked, is physical exercise. We should not only educate our patients about the benefits of regular physical activity, but also properly guide them to a physical activity program that suits their lifestyle and state of health.

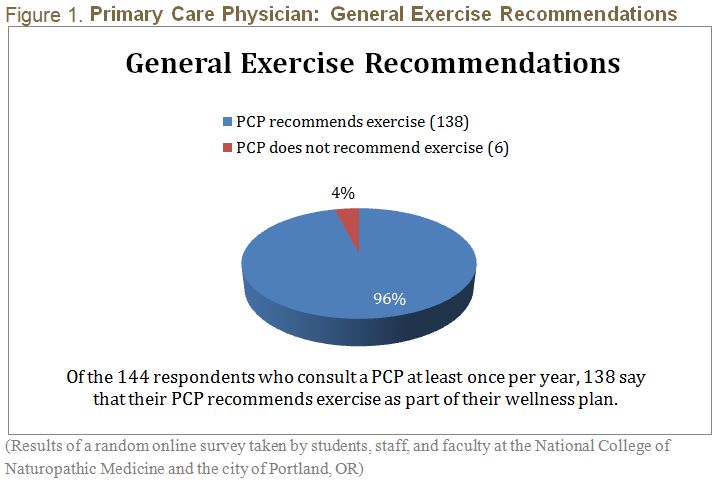

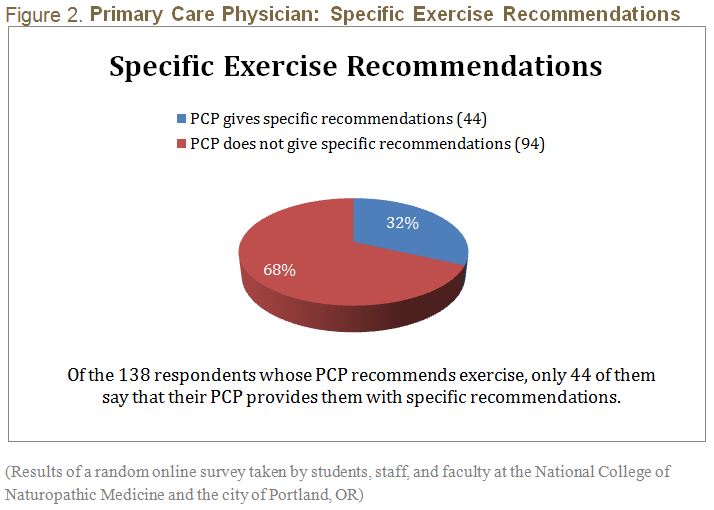

Do we truly do enough to effectively encourage our patients to get up and move? We all know that exercise is an important component of patient health. Physical activity can decrease stress, build confidence, and releases endorphins.1 Most physicians do tell their patients to increase their physical activity, but many fail to discuss a specific plan that meets their patient’s health needs (Figures 1 and 2).

Patients have endless options for physical activity: Running, walking, yoga, CrossFit, pilates, martial arts, and weight lifting are just a few of the more common types of exercise that patients may explore. Having a sizeable number of options can be overwhelming to navigate, so most patients need the guidance of their physician in selecting an appropriate activity. We need to take as much time for customizing a physical activity plan as we do for tailoring a dietary plan. Just as we talk with patients about their current diet, including dietary restrictions, diet preferences, food sensitivities, and digestive symptoms in formulating a dietary plan, we also need to talk about current and past physical activities, current health issues and fitness level, physical barriers, and patient preferences, to select appropriate types and intensity of physical activity.

A common story I hear from patients is that they became injured when they began exercising. For example, a former client of mine was advised by her physician to “start exercising” as a treatment for obesity and type 2 diabetes. She had not consistently engaged in any physical activity for over 10 years. After asking friends for recommendations, she began a high-intensity, high-impact training program and soon thereafter was injured. She could not exercise for several months as her injuries healed. Her injuries and setback in health would very likely have been avoided with proper physician guidance.

As naturopathic physicians, we are uniquely qualified to offer this specific guidance to our patients. The training we receive in anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, and biochemistry allows us to go beyond the general and broad fitness recommendations that one can find in an average health magazine. Additionally, we are trained to understand the body holistically and can apply this understanding to comprehensive treatment plans, including our patient’s physical activities. It is also important not to underestimate the value of the time spent counseling our patients. Investing this time can open a more personal conversation and strengthen the patient-physician relationship, ultimately improving patient compliance and health.

As naturopathic physicians, we are sworn to uphold 6 key principles. Engaging in a detailed discussion about physical activity with our patients is a great way to uphold these principles:

1. The Healing Power of Nature: Our bodies are meant to move. Physical activity has been proven to produce positive health outcomes.2

2. Identify and Treat the Cause: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), heart disease was the number 1 cause of death in 2009, and preliminary data for 2011 shows that it will again top the list.3 Physical inactivity has a positive correlation with risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.4

3. First Do No Harm: Naturopathic physicians need to understand that recommending physical activity without proper assessment and guidance may expose our patients to the risk of injury. Just as patients can experience adverse outcomes from overdosing on medications due to improper instruction, the same can happen when exercise is conducted without proper guidance.5

4. Doctor as Teacher: Counseling about physical activity can benefit our patients in several ways. It gives us the opportunity to teach our patients how their body works, empowering them to take charge of their own health.

5. Treat the Whole Person: Physical activity should be included as part of a complete patient history, along with personal and family history, medications, stress, and diet.

6. Prevention: Starting a patient on an appropriate activity regimen can aid in the prevention of many of the diseases that run rampant in our society. According the CDC, physical activity can improve health. People who are physically active tend to live longer and have lower risk for heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, depression, and some cancers. Physical activity can also improve health through weight control and may improve academic achievement in students.6

Physical activity is a powerful tool in helping patients to achieve balance, wellness, and good health. It can be fun, relieve stress, and prevent disease. As naturopathic physicians, it is our job to guide our patients in this very important area of wellness.

For physicians looking for specific strategies to increase physical activity in patients and the surrounding community, the CDC has composed a comprehensive document7 to help get started.

Jennifer Gibbons, ND is a 1998 graduate of National College of Natural Medicine. She has a family practice in Portland, Oregon where her practice focuses on midwifery and the primary care of children and women. She teaches pediatrics and midwifery at NCNM.

Jennifer Gibbons, ND is a 1998 graduate of National College of Natural Medicine. She has a family practice in Portland, Oregon where her practice focuses on midwifery and the primary care of children and women. She teaches pediatrics and midwifery at NCNM.

Osemekhian Okojie, ND Candidate, is a 5th year medical student at the National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, OR. Osemekhian is also a nationally-certified personal trainer through the National Academy of Sports Medicine.

Osemekhian Okojie, ND Candidate, is a 5th year medical student at the National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, OR. Osemekhian is also a nationally-certified personal trainer through the National Academy of Sports Medicine.

References

1. Heyman E, Gamelin FX, Goekint M, et al. Intense exercise increases circulating endocannabinoid and BDNF levels in humans–possible implications for reward and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(6):844-851.

2. Leckie RL, Weinstein AM, Hodzic JC, Erickson KI. Potential moderators of physical activity on brain health. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:948981.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Death and Mortality. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. Accessed December 29, 2012.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Inactivity Estimates, by County. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsPhysicalInactivity/. Accessed December 29, 2012.

5. Jones BH, Knapik JJ. Physical training and exercise-related injuries. Surveillance, research and injury prevention in military populations. Sports Med. 1999;27(2):111-125.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts About Physical Activity. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/facts.html. Accessed December 3, 2012.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/resources/recommendations.html. Accessed December 3, 2012.