Hydrotherapy Terms Defined: Fluxions, Reactions, Retrostasis, and Revulsions

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

The most interesting and phenomenal results of hydrotherapy are due to that complex process ― reaction, i.e., the part which the body itself takes in its own recuperation and healing.

George Knapp Abbott, 1914, p.30

Applications of cold water to the surface of the body set up both circulatory and thermic reactions. In revulsion pure and simple, it is desirable to obtain only the circulatory reaction.

John Harvey Kellogg, 1902, p.241

No historical review of hydrotherapy would be complete without a tribute to two American masters in this department: J. H. Kellogg and Simon Baruch. These men, above all others, have stood for the honest, scientific and practical application of water to disease.

Curran Pope, 1909, p.10

Let us begin with these definitions, protocols, and applications. What at first seems ambiguous or even superfluous in the many articles on fluxions and retrostasis, revulsions, and reactions, as we navigate through the language, protocols, and theories of our naturopathic pioneers, makes sense quickly as we explore and rediscover this lost tradition. An ideal launch point for this discussion is cold water itself.Some definitions are in order to understand the older hydrotherapy texts and to make sense of the importance of the mechanisms underlying the water applications on the body. Some of these definitions bring with them a litany of physiological explanations that originated long before the advent of modern scientific inquiry. However, their relevance is not diminished because of changes in language use and familiarity. Rather, we soon discover that the literature of this era presents us with refreshing explanations of hydrotherapy and the body. In any case, the 4 terms that show up in the writing of naturopaths and that are central to hydrotherapy are fluxion, reaction, retrostasis and revulsion. The more deeply one explores the early literature, the clearer it becomes that we ought not to underestimate the early hydrotherapists with their profound understanding of the vital purpose and function of blood circulation for the maintenance of health.

Cold Water

A dash of cold water onto the body is most often experienced as an irritation that our body reacts to with a series of responses. Cold water, in fact, generates a response on the skin not unlike vigorous rubbing or percussion. In each of these situations, the skin will turn red with an increase of blood moving to the area of the irritation. (Abbott, 1914, p.50) On the other hand, the reactions from hot water (or heat, generally) are quite different than those of cold. With prolonged heat, the reaction is passive dilation of vessels, resulting in stagnation of blood. With cold applications, the skin becomes invigorated, with increased blood circulation. This stimulating response is magnified when cold is combined with friction and/or percussion. This dynamic can be very powerful in hydrotherapy treatments and healing.

Reaction

John Harvey Kellogg wrote volumes on hydrotherapy, elucidating theory and practice in great detail in his quest to elevate the use of hydrotherapies among his medical colleagues. Kellogg explains the concept of “reaction” that is used in hydrotherapy as “one of the most complex and interesting of physiological phenomena.”(Kellogg, 1902, p.129) He goes on to say that “the term is perhaps somewhat misleading, as it suggests the idea of a single process, whereas there is a series of complicated actions and reactions.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.129) A reaction, in this regard, is a series of bodily processes resulting from exposure to either hot or cold applications to the body and its skin. The reactions created by cold are considered more intense than those caused by heat applications. This last point was well recognized by the hydrotherapists and used to the great advantage of patients – and with pride and conviction – by their naturopaths. Father Kneipp, for example, established cold water applications of very short duration in hardening or strengthening the body. Kneipp would dunk infants and children into cold water, count to 3 and immediately take them out. For his signature water application, the “gush,” 1 minute or 2 at the most, would be needed for these short cold applications.

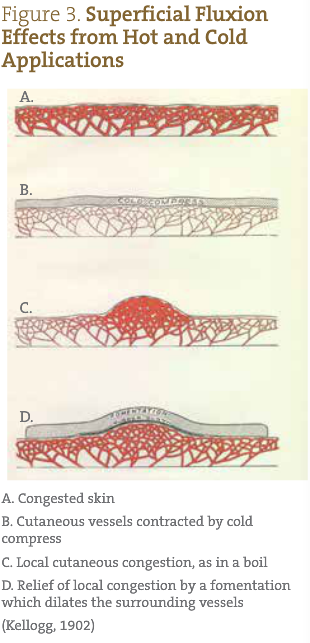

Kellogg observed 3 effects after a short cold application lasting 3 to 30 seconds. He described these as follows: 1) primary effect or action; 2) secondary effect or reaction; and 3) the final effect that involves remote effects occurring throughout the body. (Kellogg, 1902, p.130-131) The process works in that superficial blood vessels immediately contract, causing blanching of the skin and possibly goose bumps; this contraction is then followed by the reaction of dilation of the peripheral blood vessels, notably the capillaries, causing erythema and a sensation of warmth in the area. The third effect of cold water can be seen throughout the body upon the metabolism, in response to the cold application. The “restoration of homeostasis” consists of a series of modifying effects that will be discussed in a future article.

The length of time that the body is exposed to cold has a huge impact upon the kind of reaction exhibited. Short applications of cold have stimulating and tonic effects and the body reacts by immediately increasing its activities to counter the cold. Should the cold water application be prolonged to the point that the body’s efforts to counter the cold prevails, then depression of the body occurs. Warming of the peripheral blood circulation and erythema are overwhelmed and overtaken by goose bumps and intrinsic chilling.

The Thermic Reaction

The thermic reaction is a useful tool to help monitor treatment protocols. Priessnitz and Kneipp were experts in deciphering the thermic reaction to make successful diagnoses, prognoses, and the formulation of precise treatment plans. Kneipp would administer the knee gush in order to observe the reaction time of reddening of the skin. The change in color in the skin is a perfect way to gauge the thermic response. Kellogg aptly describes the color change: “This change of color begins the instant the heat communicated to the skin has been absorbed by the cold application.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.249)

A test that Kellogg used to determine reactivity of the patient was to “dip the corner of a towel in ice-water, hold the saturated towel against the bared forearm of the patient for one minute, covering a surface of at least 10 or 12 square inches. [He would] not rub the surface, [but] simply maintain contact of the cold wet towel with the skin.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.140) Kellogg continues, “On withdrawing the towel, dry the surface by light pressure with the dry end of the towel, cover to prevent slow cooling by evaporation, and note the length of time required for the occurrence of reaction, as shown by the return of redness and natural heat.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.140) Kellogg considered a good reaction time to be within 1 or 2 minutes after the application of ice water. (Kellogg, 1902, p.140)

Another test was used by Simon Baruch, an American hydrotherapist and medical doctor, to predict the reactivity of a patient undergoing cold water therapy. The process involved “passing the back of the nail of the index finger rapidly but gently across the abdomen, and increasing the pressure of the nail with a second stroke parallel to the first, [to] induce a more or less deep reddening of the irritated skin.” (Baruch, 1908, p.102) The pressure required to elicit a reaction and the quickness of the erythema to appear gave some idea of the reactivity of the patient. Baruch continues, “By applying this test frequently before each procedure one may readily train the appreciation of this test.” (Baruch, 1908, p.102)

Conditions Favoring A Reaction

Reactions can occur very soon after the cold water application. The skin will redden and feel quite warm, especially if “the patient has exercised actively just before the bath, or if vigorous friction of the skin or a hot bath has been administered.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.132) We cannot overlook or underestimate the person’s vital force as a chief factor in determining his or her reaction to cold water treatments. A vital person will exhibit a reaction, and a delay can suggest a lack of vitality. Kellogg reminds us to ensure that the room where the water treatment is being conducted is warm, and to give the patient a hot tea or beverage prior to the treatment, to influence the patient’s reaction to cold.

Conditions Impeding A Reaction

Many factors can hinder the expected reaction of a cold water application. The temperature of the water is a big factor. It is important to keep in mind that the colder the temperature, the shorter the duration of exposure. Kellogg cautions, “For very cold applications, the duration should be 1 to 5 seconds” (Kellogg, 1902, p.345), which corresponds to the practices used by Kneipp. He also notes that using water that is not cold enough can also contribute to poor responses in the patient. “Very short and very cold application” is a technique referenced frequently in the literature and needs to be noted. Prolonged cold applications can leave the patient chilled, weakened, and over-stimulated by cold. Kellogg noted that an excessive reaction to cold water treatments may generate symptoms of headache, fever, perspiration, and heart palpitations, which “indicate a too intense or too short application.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.418)

If the patient is fatigued, nervous, apprehensive of cold water, and chilly, one might expect that the cold water treatment may have done more harm than good. In these cases, special attention would be given to the patient’s needs, and the treatment plan modified to achieve positive results. Should a cold application be given and the person exhibits symptoms of chilliness, faintness, weakness, the skin remains blanched, and the reaction of erythema does not ensue, one can conclude that the person’s vitality has been compromised. When a reaction is delayed or does not evolve as expected, there are certain factors that must be considered.

Age and Vitality

The elderly and young often do not have the same vitality to initiate a reaction. Abbott notes, “Neither infants nor aged persons bear cold treatment well.” (Abbott, 1914, p.35) In the elderly, diseases can depress their vitality to react to cold water treatments. For example, the circulatory system in those with arteriosclerosis, such as found in the elderly, cannot respond to cold in reliable ways. In young children, the body has not developed adequately to respond to cold.

Disease Types

There are a number of diseases, however, which cannot react in the expected manner. Exhaustion, obesity, and rheumatic diatheses are such conditions noted by Kellogg. (Kellogg, 1902, p.135) Abbott adds anemia and emaciation to this taxonomy of conditions that render reactions extremely difficult. (Abbott, 1914, p.35) Problems with the skin, such as profuse perspiration accompanied with fatigue, sensation of chilliness or low skin temperature, and unhealthy and inactive skin, according to Kellogg, can delay reactions or prevent them from occurring at all. (Kellogg, 1902, p.135)

Body Warmth

One of the golden rules for cold water is ensuring that the patient is warm before administering any cold water application. “When the body is warm, reaction appears promptly.” (Abbott, 1914, p.35) When patients do not respond well to treatment, often the problem is that there was not enough attention given to warming the patient with physical exercises prior to the cold water. Kellogg states, “Exercise is by far the best means of encouraging reaction, as it sets in operation most fully the forces necessary for perfectly balancing the circulation, increasing heat production, and energizing all the vital functions.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.417) Like Kellogg, Abbott reminds us, “The air of the room in which the patient is treated should be warm and [s/he] should remain in a warm room after treatment until reaction is complete.” (Abbott, 1914, p.35) Abbott also points out that hydriatic treatments “are used chiefly for the purposes of lessening congestions and of assisting to reduce inflammations. If the surface of the body becomes chilled, the opposite will take place; viz., a retrostasis, or driving of the blood from the skin to the internal organs.” (Abbott, 1912, p.46)

Mental State

As well as warm environs before cold water application, Abbott and many other naturopaths call our attention in the literature to the importance of mind and body connection as a distinct influence on patient reaction to water therapies. Aversion to cold water, they report more than once, can have negative impacts on the treatments. As well, “those under great mental strain, worry, or anxiety react poorly.” (Abbott, 1914, p.36) The early naturopaths contended that it was best to determine the patient’s perception of cold water before overwhelming him or her with a disliked treatment.

Fluxion

“Fluxion” is the movement of blood, which water therapy is so effective at influencing. The blood must be healthy and the flow of blood must be not be impeded, especially when blood congestion exists. Kellogg describes blood’s importance:

The most important thing that can be done therapeutically in relation to a chronically congested organ is to increase the supply of healthy blood, not necessarily by augmenting the volume of blood which the organ contains at any moment, but by quickening the rate at which the blood passes through it. (Kellogg, 1902, p.242)

The early naturopaths were deeply confident that the healing process involved in restoring diseased tissues and organs back to health by making blood and lymph available to help remove the waste and bring nutrients for repair could be easily accomplished with “hydriatric means.” Fluxion can be further defined as increasing the movement or flow of blood in a particular part of the body. (Abbott, 1914, p.212) Massage or friction augments fluxion of blood, especially in combination with cold water application. Fluxion can also be produced by alternate hot and cold applications. (Abbott, 1914, p.216)

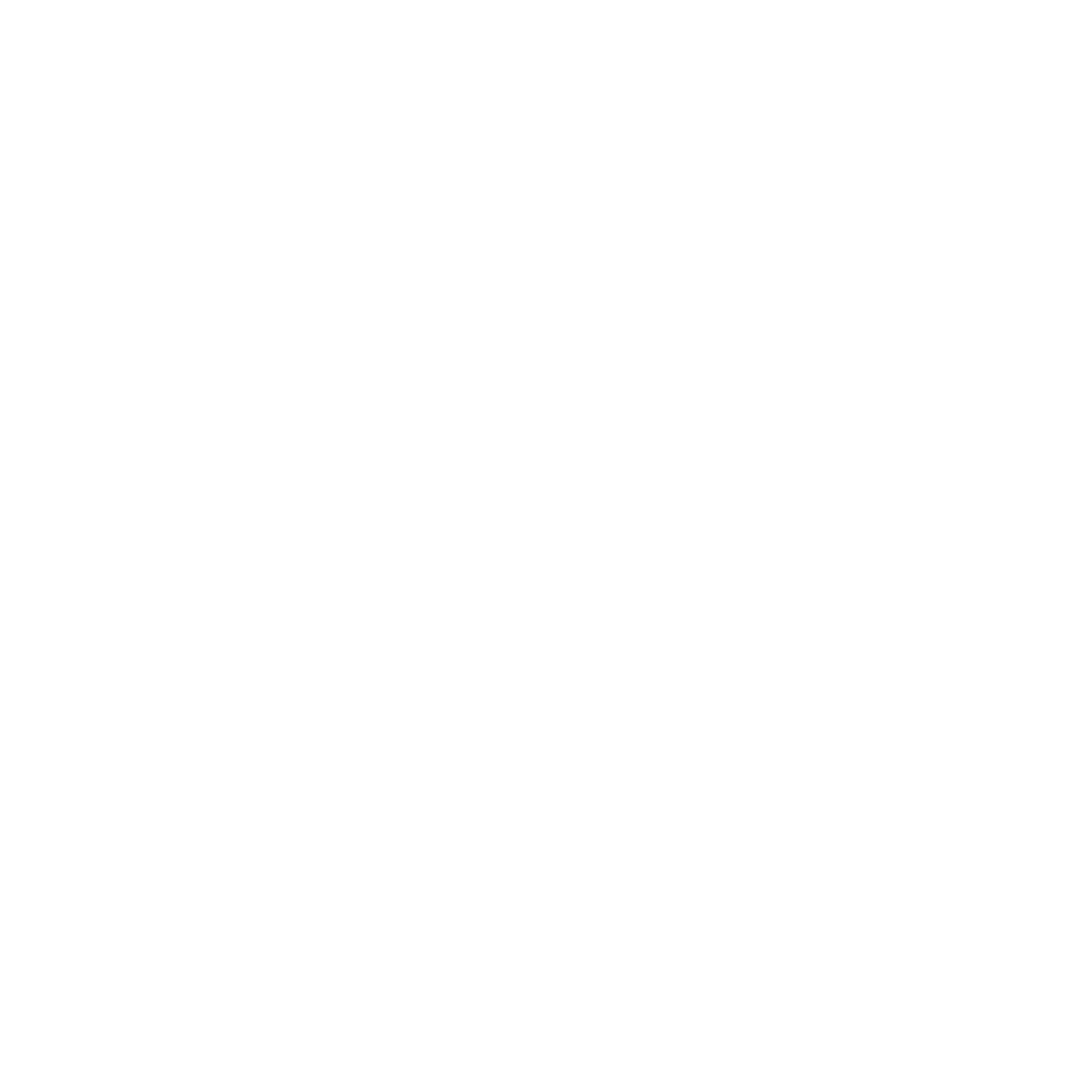

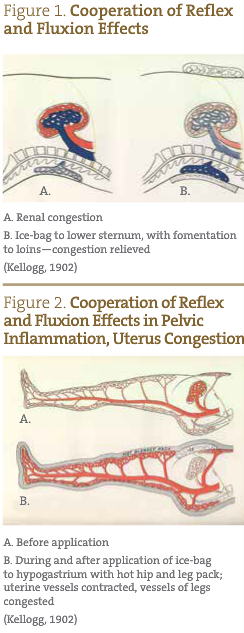

Fluxion has 4 presentations that can be used strategically (Figures 1-3):

-Increasing the rate of blood movement through an organ or tissue

-Decreasing the rate of blood movement

-Increasing the volume of blood in an area with deficient blood

-Decreasing the volume of blood in a part containing too much

(Kellogg, 1902, p.729)

Alternate hot and cold applications were used to treat an acute infection, inflammation, lymphangitis, and venous stasis. (Abbott, 1914, p.217) Abbott lists the conditions that he employed hot and cold fluxion principles to remedy. Abbott’s list includes, “Acute infections, convalescence from all local infections, chronic congestion of liver, chronic pelvic congestion, uterine subinvolution, amenorrhea, muscular atrophies, tubercular arthritis and synovitis, chronic osteomyelitis and varicose ulcers.” (Abbott, 1914, p.217) Kellogg cautions that care must be taken when using cold applications for inflammation “to avoid such procedures as may cause increased fluxion of blood toward the inflamed organ.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.246)

Two terms that help to unravel fluxion are depletion and derivation. Depletion is the reduction of congestion anywhere in the body, and the means of producing depletion is derivation. (Abbott, 1912, p.46) Derivation is the reduction of congestion by moving the excess blood to somewhere else. Depletion and derivation drew blood elsewhere by the dilation of blood vessels distally. The practical application of derivation is for acute stage of inflammation or “the first few hours of the inflammatory process.” (Abbott, 1912, p.103)

Retrostasis

“Retrostasis” is the movement of blood from the peripheral circulation to the blood vessels of the interior. Cold hydriatic applications will easily redirect blood from the skin inward to the core. Cold water treatments are essentially moving blood from one area to another, and not necessarily to adjacent areas. An example is given by Abbott: “The cold sitz bath caused an increase in the volume of [blood] of the forearm, due to retrostasis, consequent on contraction of the vessels under the influence of the cold water.” (Abbott, 1914, p.80)

Retrostasis resulting from cold applications made to the whole body causes the internal organs to become congested. Kellogg further explains this process of retrostasis. He writes, “During the first instant after the general cold application, while the internal vessels are contracted, the surplus blood, chased out of the systemic circulation, finds temporary refuge, so to speak, in the veins and the portal reservoir, from which, in the later moments, it is distributed among the internal organs.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.729-730) Retrostasis affected blood flow systemically. Kellogg explains, “If cold is applied to the lower part of the body, the blood vessels, both external and internal, contract, and the blood is driven out of the lower extremities, pelvis and lower abdomen. At the same time, the vessels of the head, chest, and arms are dilated, and the volume of blood in these parts is increased.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.730)

Revulsion

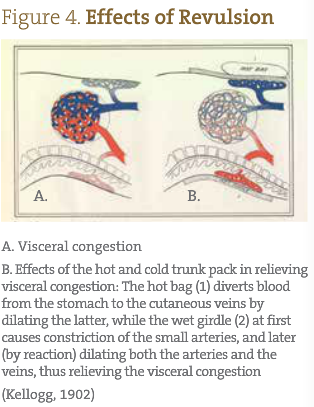

“Revulsion,” the fourth and final term in our discussion, mobilizes blood flow from one area to another with the use of cold water or hot, or both used alternatively. Kellogg gives an example of how revulsion works:

When this circulatory reaction is produced in an area of the skin supplied by an artery, a branch of which supplied some deeper structure, as in the case of an inflamed muscle or joint, a congested nerve, or an alveolar abscess, a considerable amount of blood may be by this means diverted away from the inflamed or congested part, thus affording relief from urgent symptoms by producing a local hyperemia of the skin and a collateral anemia of the affected part.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.241)

Kellogg views “Revulsion [as] perhaps most properly applied to effects produced in an internal organ, as the abdominal viscera or the brain.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.246) Although this current article is not addressing the topic of reflex theory, Kellogg established good evidence of how a cold application to one part of the body would influence another part. He continues, “A short cold application causes temporary contraction of the vessels of the skin, and likewise of the associated internal vascular area, and is quickly followed by reaction, with dilation of the vessels of both areas.” (Kellogg, 1902, p.246) (Figure 4)

Revulsion’s primary goal is to redistribute blood flow without overheating the body. To prevent the thermic response with cold applications, the hydrotherapist must be perceptively watching for the very moment of color change, at which time the cold application is stopped. The use of hot and cold applications allowed greater control of the thermic effect during a revulsive application. A headache is good example of how to use this principle of revulsion. Hot and cold foot baths can alleviate a cerebral congestion and a headache. Abbott explains, “When hot and cold are alternately applied to one part of the body, thus producing fluxion in that part, it will withdraw more or less blood from other related or distant parts.” (Abbott, 1914, p.218) The hot application causes passive dilation of the blood vessels, and the cold application “maintains for a longer time the derivation secured by the hot.” (Abbott, 1914, p.215)

Summary

In summary, fluxion speeds up the flow of blood, reaction initiates the body’s healing responses, retrostasis moves blood from the surface of the skin to the organs, and revulsion moves blood from one part to another distally.

The use of cold water applications offers a time-tested alternative to the drug solutions that our contemporary patients face. Cold water is so accessible. Running water is found in practically all homes and offices. Making these simple water-cure principles available for your patients can help when other means cannot.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References

- Abbott, G. K. (1912). Elements of Hydrotherapy for Nurses. Washington, DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association.

- Abbott, G. K. (1914). Principles and Practice of Hydrotherapy. Loma Linda, CA: The College Press.

- Baruch, S. (1908). The Principles and Practice of Hydrotherapy, 3rd ed. New York, NY: William Wood and Company.

- Kellogg, J. H. (1902). Rational Hydrotherapy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company Publishers.

- Pope, C. (1909). Practical Hydrotherapy. Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati Medical Book Company.