Melanie Stein, ND

A clinical case highlights how intravenous phosphatidylcholine and targeted membrane repair strategies supported lasting recovery in a patient with refractory Lyme and co-infections.

Abstract

This case describes a 47-year-old female high school teacher with a multi-year history of progressive neurological, musculoskeletal, autonomic, constitutional, and gastrointestinal symptoms following confirmed Borrelia burgdorferi, Babesia spp., Bartonella henselae, and tick-borne relapsing fever Borrelia infections. Despite significant but transient improvements with multiple targeted antimicrobial regimens, symptoms recurred within 1–2 months of discontinuation. Six months into therapy, environmental mold remediation resolved chronic diarrhea and stabilized postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Persistent relapse patterns and functional decline led to advanced testing, revealing profound phospholipid depletion, elevated oxidative stress markers, and mitochondrial membrane damage. Treatment with a structured IV phosphatidylcholine-based membrane stabilization protocol plus targeted oral mitochondrial and membrane repair agents yielded sustained clinical improvements. This case highlights the role of cell membrane therapy in chronic tick-borne disease recovery, particularly when the Cell Danger Response remains active despite infection control.¹

Introduction

Persistent symptoms following tick-borne infections remain a therapeutic challenge, even after appropriate antimicrobial therapy. The complexity of these syndromes often involves overlapping factors: persistent infection, immune dysregulation, environmental toxicity, and mitochondrial impairment.

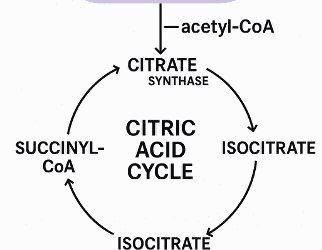

The Cell Danger Response (CDR), as described by Naviaux, provides a unifying framework: cellular metabolic shifts toward defense mode can persist long after the initiating insult, resulting in ongoing dysfunction in energy metabolism, immune signaling, and tissue repair. In this context, mitochondrial membranes, rich in phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage. Lipid peroxidation, driven by reactive oxygen species and inflammatory mediators, disrupts membrane fluidity, damages lipid rafts critical for cell signaling, and perpetuates inflammation.²

This report details the successful integration of antimicrobial therapy, environmental remediation, and targeted cell membrane stabilization in a patient with chronic tick-borne disease and mold exposure.

Case Presentation

Patient: 47-year-old female high school teacher.

History: Multi-year progression of:

- Neurological: cognitive impairment, slowed processing, memory lapses, dizziness, visual changes.

- Musculoskeletal: migratory joint/muscle pain, morning stiffness, muscle weakness.

- Autonomic: air hunger, temperature dysregulation, orthostatic intolerance.

- Constitutional: severe fatigue, post-exertional malaise, night sweats, insomnia.

- Gastrointestinal: chronic diarrhea (resolved after mold remediation), bloating.

Timeline of Key Events

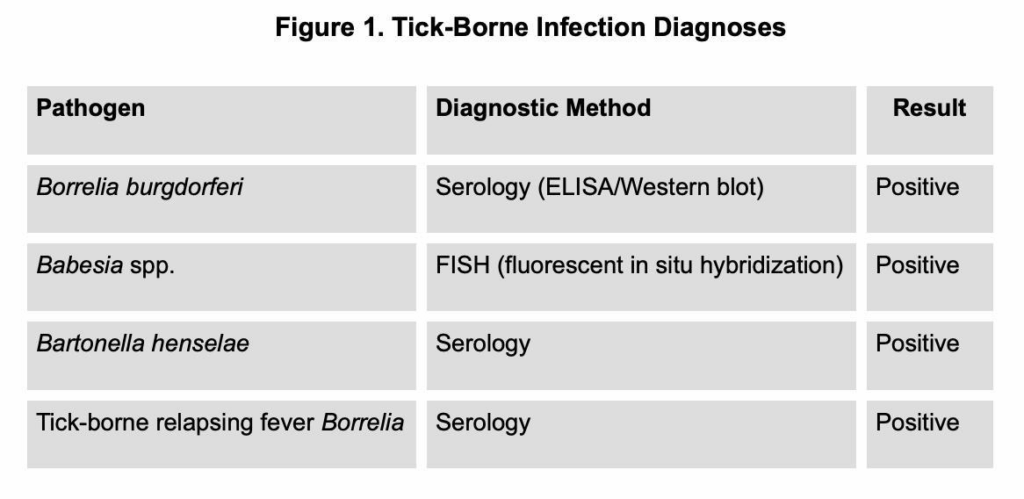

- Diagnosis: Serology and FISH confirmed multiple tick-borne infections (see Figure 1).

- Antimicrobial therapy:

- Cefdinir: improved cognition and joint pain.

- Minocycline + Bactrim: improved neurological and neuropathic symptoms.

- Added rifampin: alleviated Bartonella-related neuropathic pain.

- Discontinued Bactrim, added methylene blue: improved mental clarity and stamina.

- Each regimen was maintained for 3–7 months.

- Pattern: Within 1–2 months of stopping each regimen, relapse occurred (fatigue, brain fog, pain, autonomic symptoms).

- Environmental milestone: Six months into therapy, mold remediation resolved chronic diarrhea, eliminated the need for weekly IV hydration, and stabilized POTS.

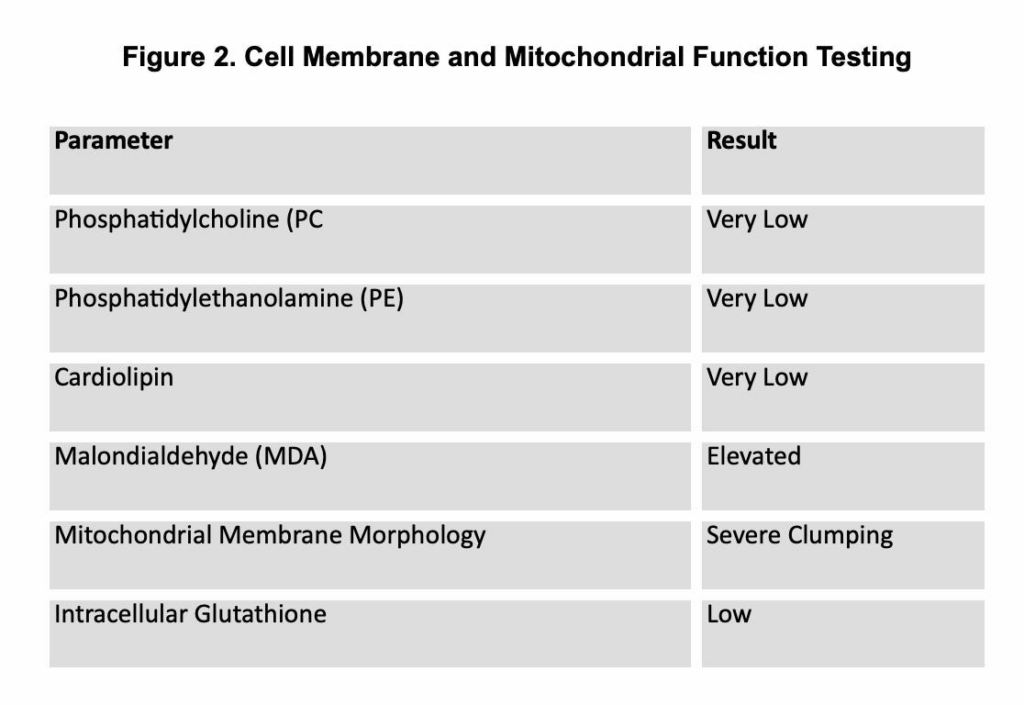

- Advanced testing: Near the end of 2 years of antimicrobials, persistent symptoms prompted cell membrane and mitochondrial evaluation (see Figure 2).

Diagnostic Testing

Figure 1. Tick-Borne Infection Diagnoses

Figure 2. Cell Membrane and Mitochondrial Function Testing

Intervention

- IV Membrane Stabilization Protocol:

- Bag 1: 250 mL D5W + 2,000 mg of Phosphatidyl Choline

- Bag 2: 100 mL NS + 2g glutathione

- Bag 3: 100 mL NS + 1g magnesium sulfate + 5 mg zinc sulfate

. - Bag 4: 100 mL NS + 2 mg manganese chloride + 100 mg

pyridoxine

- Push 1: 10 mg methylcobalamin

- Push 2: 9 mL Normal saline + 10 mg leucovorin

- Oral Support Regimen:

- Phospholipids: replenish Phosphatidylethanolamine and support membrane synthesis.

- Acetyl-L-carnitine: enhances mitochondrial fatty acid transport and energy production.

- Coenzyme Q10: supports electron transport chain function.

- Oral glutathione: antioxidant and detoxification support.

- Sodium butyrate: reduces MDA, supports colonocyte health, and promotes gut barrier repair.

- Binders: assist in toxin elimination.

- Multivitamin: broad-spectrum micronutrient repletion.

Outcome

Over several months of IV and oral therapy, the patient experienced:

- Increased stamina and exercise tolerance.

- Reduction in neuropathic pain and brain fog.

- Improved thermoregulation.

- Sustained remission of diarrhea and stable POTS.

Repeat membrane testing showed improved phospholipid levels and reduced oxidative stress markers.

Discussion

Malondialdehyde (MDA) serves as a well-established biomarker of oxidative stress via lipid peroxidation, reflecting the breakdown of polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes.² In chronic tick-borne disease, the sustained generation of reactive oxygen species, driven by persistent inflammation, nitric oxide imbalance, and the direct damaging effects of pathogens like Borrelia burgdorferi, elevates MDA levels and causes progressive membrane degradation.³

Cell membranes depend on specialized microdomains known as lipid rafts, rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids, to facilitate immune receptor clustering, antigen presentation, and critical intracellular signaling.⁴ When membrane lipids are oxidatively damaged, lipid raft integrity is disrupted, contributing to impaired immune regulation and the perpetuation of inflammation even after the primary infectious burden has decreased. Disruption of these lipid rafts has also been shown to be exploited by Borrelia burgdorferi for immune evasion and host cell entry, further linking oxidative membrane injury with persistent infection dynamics.⁴,⁵

Phospholipids such as PC, PE, and cardiolipin are vital for mitochondrial structure, cristae formation, membrane fluidity, and ATP production.⁶ Their depletion, accelerated by ROS-induced oxidation, inflammatory signaling, and increased membrane turnover, leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and supports a chronic, hypometabolic state characteristic of the CDR.⁷ Growing evidence underscores the essential role PC plays in mitochondrial protein import and the stability of membrane complexes, including SAM and TIM23.⁸

To repair these deficits, we implemented a targeted multimodal repair strategy. Intravenous PC rapidly replenishes membrane PC stores, improving mitochondrial fluidity and function.⁹ Because IV PC does not contain PE, oral phospholipids were included to ensure comprehensive membrane repair. Glutathione, delivered both IV and orally, served to neutralize ROS and lower oxidative stress.¹⁰ Sodium butyrate supported mucosal barrier health, reduced lipid peroxidation, and restored redox balance.¹¹,¹²

Additional mitochondrial cofactors such as acetyl-L-carnitine and CoQ10 supported electron transport and metabolic repair,¹³,¹⁴ , and were coupled with trace minerals and B vitamins to provide enzymatic support for phospholipid synthesis and oxidative metabolism. Rebuilding this structural and metabolic platform allowed the patient’s physiology to shift from a prolonged CDR state toward restoration and adaptability. After completing a final three-month antibiotic regimen without relapse, she sustained a breakthrough in her care, suggesting that structural repair is a prerequisite to durable recovery in complex infectious and environmental illness.

Conclusion

This case illustrates that infection suppression alone may be insufficient in chronic tick-borne illness, particularly when environmental factors such as mold exposure have compounded mitochondrial and membrane injury. Even after antimicrobial therapy and environmental remediation, persistent membrane and mitochondrial deficits can keep patients locked in the CDR, preventing complete recovery.

Objective evidence of phospholipid depletion and oxidative stress should prompt consideration of cell membrane restoration therapy, including IV PC, mitochondrial cofactors, and targeted oral supplementation, to repair structural deficits, restore immune communication through lipid raft stabilization, and enable the metabolic shift from defense to repair. By integrating metabolic-structural repair with antimicrobial therapy and environmental remediation, clinicians can address both the infectious triggers and the terrain-level dysregulation they leave behind, creating a pathway to durable remission in otherwise refractory cases.

The sustained recovery in this patient following a structured multimodal repair strategy highlights the broader therapeutic principle emphasized in the discussion: without restoring lipid raft integrity, mitochondrial phospholipid stability, and redox balance, antimicrobial therapy alone risks leaving patients vulnerable to relapse. This case demonstrates that targeted phospholipid therapy, combined with cofactors and antioxidants, not only repaired structural and metabolic deficits but also unlocked the ability to achieve durable remission, underscoring its critical role in the management of complex tick-borne and environmental illnesses.

Dr. Stein is a licensed Naturopathic Physician in Portland, Oregon, who specializes in restoring health at the cellular level through Cell Membrane Therapy. She helps patients with complex chronic illnesses—including Lyme disease, mold toxicity, MCAS, POTS, and autoimmune disorders—by repairing and revitalizing cell membranes to improve energy, reduce inflammation, and enhance detoxification. Her approach blends cutting-edge therapies with individualized care plans that address root causes and support long-term healing.

References

- Naviaux RK. Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle—A new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion. 2019;46:278-297. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2018.08.001

2. del Rio D, Stewart AJ, Pellegrini N. A review of recent studies on malondialdehyde as toxic bioactive molecule. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(12):1415-1423. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.09.009

3. Ratajczak-Wrona W, Jabłońska E, Pancewicz SA, et al. Evaluation of serum levels of nitric oxide and its biomarkers in patients with Lyme borreliosis. Prog Health Sci. 2013;3(2):26-32.

4. Sezgin E, Levental I, Mayor S, Eggeling C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(6):361-374. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.16

5. Kulkarni R, Wiemer EAC, Chang W. Role of lipid rafts in pathogen-host interaction: a mini review. Front Immunol. 2022;12:815020. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.815020

6. van Meer G, de Kroon AI. Lipid map of the mammalian cell. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 1):5-8. doi:10.1242/jcs.071233

7. Grimm A, Eckert A. Brain aging and neurodegeneration: from a mitochondrial point of view. J Neurochem. 2017;143(4):418-431. doi:10.1111/jnc.14037

8. Schuler MH, Di Bartolomeo F, Böttinger L, et al. Phosphatidylcholine affects the role of the sorting and assembly machinery in the biogenesis of mitochondrial β-barrel proteins. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(44):26523-26532. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.687921

9. Choudhary RC, Kuschner CE, Kazmi J, et al. The role of phospholipid alterations in mitochondrial and brain dysfunction after cardiac arrest. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(9):4645. doi:10.3390/ijms25094645

10. Shan XQ, Aw TY, Jones DP. Glutathione-dependent protection against oxidative injury. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47(1):61-71. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(90)90045-4

11. Chen J, Vitetta L. The role of butyrate in attenuating pathobiont-induced hyperinflammation. Immune Netw. 2020;20(2):e15. doi:10.4110/in.2020.20.e15

12. Cani PD, Van Hul M, Lefort C, Depommier C, Rastelli M, Everard A. Microbial regulation of organismal energy homeostasis. Nat Metab. 2019;1(1):34-46. doi:10.1038/s42255-018-0017-4

13. Jones LL, McDonald DA, Borum PR. Acylcarnitines: role in brain. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49(1):61-75. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2009.08.009

14. Littarru GP, Tiano L. Clinical aspects of coenzyme Q10: an update. Nutrition. 2010;26(3):250-254. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2009.08.008