Nature Cure Clinical Pearls: According to Kuhne

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

Natural inclination drew me to science; severe sickness and sad experiences with orthodox physicians led me to the Nature Cure. – Louis Kuhne, 1901, p.13

We must never forget that everything we put into the stomach has to be digested. – Louis Kuhne, 1901, p.20

Those foods which are most easily digestible are exactly those which are best suited to nourish the body. Over nutrition, also, is least liable to occur where the food is easily digested. – Louis Kuhne, 1918, p.44

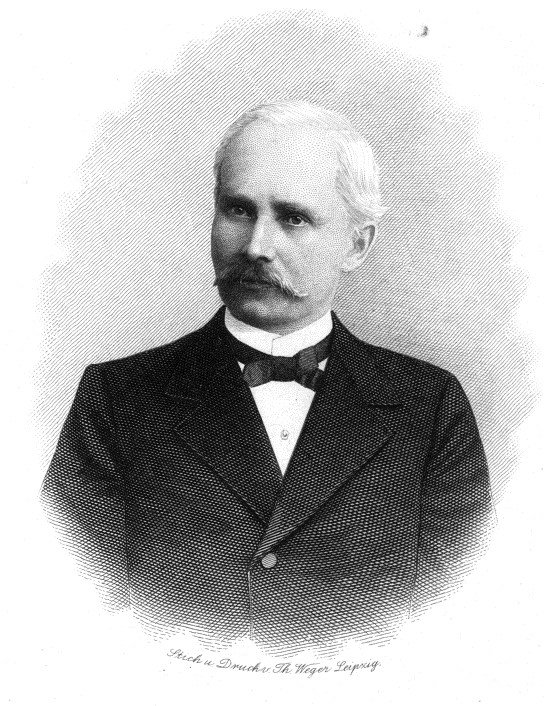

Louis Kuhne (1835-1901) (Figure 1) stands rightfully tall on the naturopathic landscape because he indeed contributed hugely to its philosophical and knowledge base. Kuhne’s understanding of healing came first-hand from his personal suffering with stomach cancer and lung complaints. When he was 20 years old, he experienced severe violent pains in the lungs and head. (Kuhne, 1901, p.2) Witnessing the death of his father from stomach cancer and seeing his chronically ill mother repeatedly mistreated by physicians were strong catalysts that directed his life. He exhausted medical doctors’ abilities to alleviate his suffering and then turned to natural medicine, which helped him. But not quite enough, as it turns out.

Figure 1. Louis Kuhne, 1835-1901

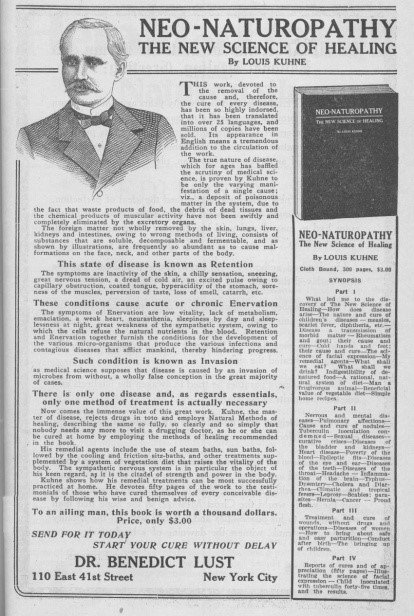

Unable to alleviate his health problems using conventionally available methods, his love and observations of Nature guided him to find enduring solutions. After suffering for nearly a quarter of a century, his experimentations on himself led him to a discovery that culminated in his writing 2 important books: The New Science of Healing (1891), and Science of Facial Expression (1895), which would guide generations of Naturopaths around the world in the 20th century. By the seventh German edition in 1894, The New Science of Healing (Figure 2) had been published in 25 languages. So popular was the work of Kuhne that his teachings went viral globally. By 1899, his book had reached its 50th edition and was seminal in uncovering “Nature’s definite and immutable laws.” (Kuhne, 1899 Preface, v)

Figure 2. Kuhne Book Ad, 1917

Unity of Disease, Unity of Cure

Kuhne discovered that there were many manifestations of disease but only 1 cause for all of them. In treating disease, Kuhne also determined that, just as there was only 1 cause for disease, there was 1 cure for disease. Called the “unity of disease” and “unity of cure,” this seemingly oversimplified concept of disease and cure had at its core immensely valuable tenets that actually worked clinically. The last chapter in The New Science of Healing comprises 133 cases providing proof that Kuhne’s theories had merit.

It is important to note that Henry Lindlahr constructed his Nature Cure philosophy and his theories principally by borrowing from the work of Kuhne and expanding them into his own. Lindlahr’s use of many of the same terms used by Kuhne resurrected a strong foundation for Nature Cure, and for naturopathic medicine. The accessibility and approach of Lindlahr’s books had an immense impact on the traditional roots of early naturopathic principles and philosophy in America.

What is Disease?

Kuhne began with 1 very pertinent question in his search for creating health: what is disease? In order to understand how to heal, one first needs to know what it is that needs to heal. In his view, disease was “the presence of foreign matter in the system.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.18) The notion of foreign or morbid matter – an antiquated term from the 19th century – merits review and restatement so that we can better appreciate Kuhne’s theories in our own time.

Environmental pollutants, food additives, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), solvents, and the myriad 100 000 chemical compounds that inundate modern times were unheard of when Kuhne was formulating his understanding of “morbid or foreign matter.” He understood foreign matter as substances introduced into the body that had no place or use. More appropriate terms to convey the meaning of morbid or foreign matter are endotoxins and exotoxins. When materials foreign to the body’s natural propensity for dense nutrients and balance accumulate within the body, they become morbid over time and because of poor diet and lifestyle habits. We can turn to observations of people, or even of ourselves, to sharpen our understanding of the process meant by Kuhne’s notion of morbid matter.

As we drill down into this understanding, we may want to begin by acknowledging that our love of food can lead us into a lifestyle of irresistible cravings rather than one where appetite is dictated by hunger. In this connection, the 2 portals for foreign matter to enter the body are either by the nose and lungs, or by the mouth into the stomach. The lungs are not as corruptible as the stomach. According to Kuhne’s definition, morbid or foreign matter is cumulative. To illustrate, if a person smokes for the first time, the lungs will rebel, and coughing will ensue in an attempt to clear the lungs. However, Kuhne notes, “As soon as we fail to promptly obey the senses of smell and taste, they grow more lax in the fulfilment [sic] of their duty, and gradually allow harmful matter to pass unchallenged into the body.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.19) It is in their accumulation, poor processing, and in the body’s eventual tolerance of them that morbid matter gains ascendancy over health.

The stomach, as mentioned earlier, is naturally resilient to a bad diet or overeating. Kuhne is quite articulate, though, about how we slip into bad habits of diet that contribute to the potential morbid matter which invades and stays in our bodies. In his words,

The injurious effects of a wrong diet are slower and less striking. The boundary between natural food and deadly poison is very wide. The step from the natural to the unnatural is often so small as to be at first scarcely perceptible. But as we know that foreign matter only forms as the result of wrong food, that is, can only arise in the body as the result of bad digestion, it must be our task to avoid such wrong foods and such bad digestion. (Kuhne, 1918, p.42)

Alternatively, consciously choosing foods that are easily digested increases the amount of vitality or vital force. Easily digested foods, such as those in their natural state, like fresh fruits and vegetables, require less time to travel through the digestive tract and generate more vital energy. In this process, they do not tax the body’s systems in the way that inflammatory and otherwise inappropriate foods can and do.

How easy it is to get used to foods with no nutritional value. In contemporary society the path of foreign and morbid matter is still there, and even more perniciously, given current values in eating and food production. In Kuhne’s era, the problems of food were associated with overeating and the consumption of alcohol, condiments, and spices. Unripe fruit was chosen by Kuhne as the best example of food easily digested. In some, diarrhea resulted from eating unripe fruit, but this outcome illustrated how the body rids itself of an overload of food.

Denatured Food

Kuhne advocated a vegetarian diet, and long before raw plant food was considered healthy, he also considered cooked foods as less than optimal. In fact, he went so far as to say, “all foods which we have to change by cooking, smoking, spicing, salting, pickling, and putting in vinegar, lose in digestibility, and as regards vitality, are far inferior to food in its natural condition.” (Kuhne, 1918, p.44)

Foods made into fluids, such as soups, were more difficult to digest because the need for chewing was bypassed. Soup ingredients in their natural state would be solid and require mastication. In an age when smoothies and juices are inhaled and at the same time are considered health food, is it a wonder that constipation persists?

Another category of foods which Kuhne considered to be injurious to the health included “foods which in their natural form create disgust and nausea … however good they may taste when cooked.” (Kuhne, 1918, p.44) The flesh of animals fell under this category. “No one would ever think of biting into a living ox, or eating raw sheep’s flesh. Our instinct and natural feeling may be misled by seasoning and dressing.” (Kuhne, 1918, p.44) Kuhne held strictly to the idea that “food precisely in the form Nature gives it to us, is always the best for the digestion.” (Kuhne, 1918, p.46)

The importance of fiber in the diet was not overlooked by Kuhne. White flour was another example of denatured food. Grains stripped of their bran and made into bread was a concern for constipation.

Digestion as Fermentation

In order to convert food into the building blocks that constitute a living body, foods undergo a process of fermentation that is normal. The body assimilates as much as it needs and excretes what is not needed via the intestines, kidneys, and skin.

Kuhne often took examples from Nature to explain his concepts of health and disease. He writes, “Sometimes, we observe how animals completely digest, in a very short time, such apparently indigestible things as tendons and bones. If we examine the excrements of such animals, we find absolutely no undigested pieces of bone.” (Kuhne, 1918, p.47) In humans, he explained, the contrary occurs: food often remains a whole week or more in the bowels and gives rise to abnormal conditions of fermentation. The body is then required to expel these injurious byproducts of inadequate digestion through the various excretory organs.

When foods are altered by cooking, preservatives, or chemicals, a longer time is needed for the body to digest these foods by fermentation. The time spent in the digestive tract is longer, causing an increase of internal heat, and darker and drier stools. (Kuhne, 1918, p.47) Longer transit time in the bowels leads to an abnormal progression of fermentation which finds no exit, hence depositing in the skin and blood. Kuhne called this state “encumbrance with foreign matter.”

Overeating

Today, problems of obesity trump many of the other health problems we encounter as doctors. An abundance of food, especially the calorie-rich and nutrient-deprived sorts, is eagerly consumed, and our obsession with quantity over quality compounds the problems caused by overeating. Kuhne would have described our eating habits as unnatural.

What is the right amount of food for a person with “a diseased stomach” was another question asked by Kuhne. He writes, “One apple the debilitated stomach can digest; two would be too much. All excess is poison for the body.” Some healthy people claim to have a perfectly iron-clad digestion, capable of eating anything. Kuhne is quick to remind them and us that any amount of food beyond what is needed by the body is excess and “poison for the body and if not excreted goes to form foreign matter in the body.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.20) The way to keep the body in a state of health was to practice moderation in eating.

Foreign Matter

Foreign matter is a simple term that expresses precisely what it is. Foreign matter, in Kuhne’s view, simply did not belong in the body, and the emunctories should remove it through the skin, lungs, kidneys, and bowels. Kuhne counted unhealthy food among foreign matter. He taught that if morbid or foreign matter accumulates so that it is not eliminated, the body then must find a place to store it. Because we are unable to use the harmful waste deposited in the body, our circulation and digestion become adversely affected.

The timeline for foreign matter to accumulate and do damage is slow and insidious. Symptoms are silent in the beginning. “Only after a considerable period does [the patient] become conscious of a disagreeable change in his condition. He no longer has the same appetite and he is incapable of the same amount of work.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.21)

Kuhne is credited with making the observation that the early Naturopaths adopted and considered exactly right. “Disease begins in the stomach,” Kuhne declared. He also noted, “The foreign substances are chiefly deposited in the abdomen and finally spread through the whole body.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.22)

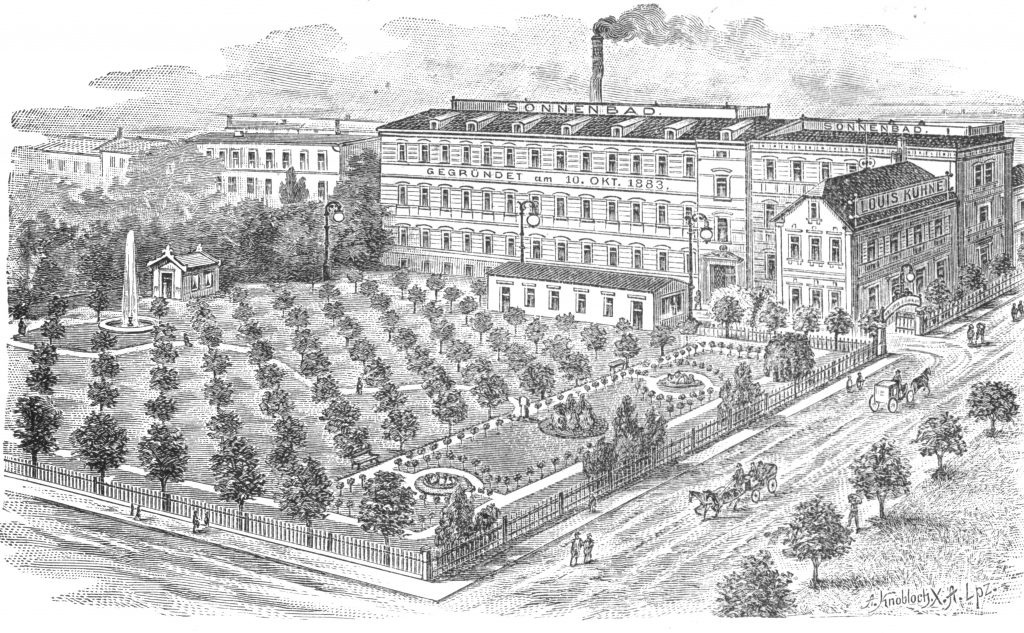

Figure 3: Kuhne Clinic, 1901

Removal of Foreign Matter

Fermentation to Fever

Kuhne referred to the microflora of the gut as microscopic fungi. He also created a theory of inflammation as beginning in the digestive tract with the accumulation of morbid matter, fermenting and creating heat that would be expressed as a fever. “Fever is fermentation going on in the system [body].” (Kuhne, 1901, p.24) The relationship between fever and the active process of disease was intertwined. He states, “There is no disease without fever and no fever without disease.” (Kuhne, 1902, p.10) Kuhne rationalized that this fermentation process needed a vent through which to leave the body. Fever unabated in the body with no outlet would ultimately lead to death.

The primary purpose of Kuhne’s therapeutic treatments was the removal of foreign matter. “To merely drive the morbid matter from one part of the body to another, to confine it, and allow it to dry up: all this is no cure but simply suppression of symptoms.” (Kuhne, 1902, p.99) When foreign matter is present, fermentation arises and fevers result. “If … morbid matter has in a suitable manner been removed from the body, the disease itself disappears.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.18)

Steam Baths

Perspiration is the body’s answer to a compromising fever. Perspiration was how Kuhne began his protocol for diseases in an attempt to remove foreign matter/disease from the body. “The steam bath is the most reliable means there is of restoring the skin to regular action.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.100) Lying on a specially constructed table allowing the passage of steam to reach the parts of the body that were exposed, patients would lie down naked and supine, and be covered by a wool blanket. Pots of boiling water were placed underneath the table. Kuhne had devised burners to produce a continuous production of steam. Today, with modern appliances, the steam bath is easily carried out. After 10 to 15 minutes, the patient would turn over to steam the chest and abdomen.

Perspiration is the primary goal. “The instant the sweat breaks out, the fermenting masses gain a vent, and the tension of the skin and febrile heat both abate.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.31) If the patient does not perspire while supine, then when turned over, perspiration should come very easily. “Persons who do not perspire readily, should keep the head covered [under the wool blanket]; this will not be found to be so disagreeable as may at first be imagined.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.103) Patients following Kuhne’s protocol perspired for 15 to 30 minutes. Areas of the body that were more riddled with toxicity or morbid matter tended to perspire with difficulty.

“Weak persons, such as seriously ill, more especially nervous patients, should never take steam baths.” (Kuhne, 1901, p.103) Sun baths are preferred for weak patients, as well as friction sitz baths and hip baths. (Kuhne, 1901, p.103)

Hip Baths

Closing the skin pores and cooling the body after a steam bath were done by taking a friction hip bath using water in the range of 68° to 81°F/20° to 27°C. Before or after the sitz bath, the whole body was very quickly washed to remove perspiration and to cool the body. (Kuhne, 1901, p.104) Another purpose of hip or sitz baths was to mobilize the foreign matter from areas of the body, principally the abdomen, that remain undisturbed. After the hip baths and washing of the body, measures to ensure that the body was warm again included either exercise for strong-abled patients, or bed rest for weak and sick patients. (Kuhne, 1901, p.104)

Conclusion

Kuhne advocated a healthy vegetarian diet as the basis of his new science of healing. He argued that “unnatural food can never be thoroughly digested, and if consumed daily,” leads to an accumulation of endotoxins and what he called foreign matter, and consequently to a diseased state. (Kuhne, 1902, p.27) Kuhne transformed his factory, which he operated successfully for 24 years, into an extremely large clinic (Figure 3) to treat conditions that originated in this process of accumulated foreign and morbid matter.

Some examples of diseases that he encountered include cancer, tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, rheumatism, migraines, obstinate constipation, paralysis, epilepsy, whooping cough, etc, etc. His armamentarium consisted essentially of dietetic counseling, the steam bath, and the friction hip bath. Using these therapies, his ability to help patients remains a triumph, and in so many ways unparalleled to this day.

References:

Kuhne, L. (1901). The New Science of Healing. London, England: Louis Kuhne Publisher, p. 460.

Kuhne, L. (1902). Science of Facial Expression. London, England: Louis Kuhne Publisher, p. 132.

Kuhne, L. (1918). What shall we eat? What shall we drink? The digestive process. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXIII (1), 42-60.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, a naturopathic physician licensed in Oregon, has been practicing since 1994. She incorporates nature-cure approaches such as balneotherapy, hydrotherapy, and breathing therapy into her practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member and works as the Rare Books Curator at NUNM. She has completed the 11th book in a 12-volume series, The Hevert Collection, based upon Benedict Lust’s original journals. She is also the founder of the Breathing Academy, which trains NDs in the breathing therapy, Buteyko. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko has established a traditional naturopathic clinic, Manitou Waters, in Manitou Beach, Saskatchewan, which is scheduled to open in August 2019.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, a naturopathic physician licensed in Oregon, has been practicing since 1994. She incorporates nature-cure approaches such as balneotherapy, hydrotherapy, and breathing therapy into her practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member and works as the Rare Books Curator at NUNM. She has completed the 11th book in a 12-volume series, The Hevert Collection, based upon Benedict Lust’s original journals. She is also the founder of the Breathing Academy, which trains NDs in the breathing therapy, Buteyko. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko has established a traditional naturopathic clinic, Manitou Waters, in Manitou Beach, Saskatchewan, which is scheduled to open in August 2019.