Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

In every period of the World’s progress, men and women have received the greatest strength and inspirations direct from nature.

-Otto Carqué, 1905, 157We are constantly violating every one of the simple but rigid laws which nature has ordered for the preservation of our mental and physical health. We do not eat as we ought to; we do not exercise as we should; we do everything wrong.

-Carl Strueh, 1908, 126All the year round enthusiasts may be found there [Butler Yungborn], enjoying its restful quiet, its closeness to nature, and the healthful ozone that , laden with the aroma of its pines and cedars, brings ‘healing on its wings.’

-Austen J. Shaw, 1911, 146

In first issue of the English edition of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, Benedict Lust posts an advertisement for the Sanatorium “Bellevue,” in Butler, New Jersey along with several other nature cure sanatoriums. (Lust, 1900, 16) This ad is significant because it establishes a few facts that may pass us by if we did not heed the fine print. The advertisement was typical for the era of sanatoriums so popular in North America as venues for natural healing at the turn of the twentieth century. In this particular ad, we witness the first alliance between Benedict Lust who is depicted as the attending Hydropathic Physician, and Miss Louisa Stroebel, the Proprietress of “The Bellevue”.

September 15th, 1896, the Birth of Naturopathy

Benedict Lust recounts, “On September 15, 1896, I opened my first business, an original all-out health food and Kneipp supply store on [111] East 59th Street, New York.” (Boyd, 1999, 44) Not only did he begin his first business in America on this date, but he attributed this date to “the birth of the Nature Cure movement.” (Boyd, 1999, 44)

In this same year, in order to promote his business interests, he also began publishing a paper in German, the Americanish Kneipp Blätter, which helped his sales in the store but also to fulfill a promise to Sebastian Kneipp. He states, “To spread the message of the Kneipp cure in the New World, as Kneipp had asked me to do, required something more than merely a store and treatment quarters.” (Boyd, 1999, 46) Publishing was the “something more”. These publications caught the attention of many interested in health and the water-cure therapies of Kneipp. While Benedict’s brother, Louis, took care of the bakery and health store, Lust was busy administering Kneipp treatments.

Soon, requests to learn how to do these treatments lead to “the first school of Naturopathy in U.S., namely the American School of Naturopathy.” (Boyd, 1999, 48) The demand upon Benedict Lust to teach Kneipp Water Cure and Massage was huge. He states, “The number of my students increased so markedly, that larger quarters became necessary. I opened the first Nature Cure sanitarium and College in the United States at 237 East 58th Street, NYC.” (Boyd, 1999, 48) This move would not be the last for Benedict Lust. Perusing the Lust journals, one soon discovers numerous addresses throughout the years, revealing that Lust moved around a lot.

The Bellevue

In the 1900 May issue of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, a full-page article features nine water cure sanatoriums located in New York, New Jersey and New Orleans, one of which belonged to Miss Stroebel. Her sanatorium figured as a prominent nature cure establishment offering patients therapies based upon the Kneipp and the Rikli system, such as “light-, air-, and sun-baths.” (Lust, 1900, 79) The location of her sanitarium couldn’t have been more ideal. Butler, New Jersey was “within forty miles of Manhattan Borough” (Lust, 1906, 117) and “only one hour’s ride from New York on the Susquehanna and Western Branch of the Erie Railroad.” (Lust, 1913, 496) New York City was home to many city dwellers aching for country fresh air and to escape the hustle and bustle of the city. Alongside Louisa’s ads are large, full-page ads that Benedict Lust placed to advertise his college and health products. Both had a passion for all things Kneippian and it seems inevitable that their businesses quickly intersected.

Those who flocked to the Bellevue Sanitarium were ever increasing and soon Louisa needed someone to help manage the clinic operations. Benedict Lust took the position of the chief medical director and assigned his graduates to work during the week at the Bellevue while he conducted his college and business in the city. Lust sent and recommended many of his urban patients to Butler to find serenity and health away from the hectic routines and stresses of city life. Lust describes this period as follows: “Each weekend I made it a point to visit The Bellevue which I found to be also responsible (in no small way) for increasing my own business at my own establishment in New York.” (Boyd, 1999, 51)

In 1900, Benedict Lust had firmly established himself as the editor of The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly which would be re-named two years later (1902) The Naturopath and Herald of Health. Lust was also “the director of the New York Naturopathic Institute and College, 135 E. 58th St.” near Lexington Ave. (Editorial staff, 1901, 163) The union between Louise and Benedict seemed fated. Their businesses were slowly entwining and their passion to change the world of health would emerge as not only a shared vision, but also as a unified mission.

Louisa Stroebel was no ordinary woman of her times. She was a successful business woman with financial security, properties and an independence rarely seen in women at the time. Her life experiences took her to England to study “curative work” where for several years she was “personal aide to Lady Cook, the famed suffragist leader, making three trips around the world with her.” (Boyd, 1999, 51) Benedict Lust describes meeting his future wife: “Louise was a healthy, strong, and attractive young woman and I was attracted to her.” (Boyd, 1999, 51) It seems that Lust also recognized in Louisa an equal partner who would be up to the challenge of what he understood to be higher missions in life to which they were both aligned. In 1900, as a regular member of the staff at Bellevue, Benedict requested her hand in marriage and with the help of Louisa’s brother, Father Stroebel, she accepted.

Miss Louisa would become Mrs. Lust the following year on June 11th, 1901 and the Bellevue Sanitarium would undergo a name change as well. By July, 1901, a month after their wedding the first changes were noted by an infomercial published in the Lust publication. The Bellevue Sanatorium was renamed “Jungborn” located at Bellevue. The time was right for Lust to publish a Prospectus that outlined the goals and the objectives of the Naturopathic school in New York City and the treatments given at the new Jungborn at Butler, New Jersey.

Jungborn, Butler, New Jersey

The Butler, New Jersey sanatorium was the same establishment with a new name and a reinvigorated destiny. It would be instrumental in the direction that Naturopathy would go. The significance of the name “Jungborn” in the branding of the Butler sanatorium reflects the influences occurring for Benedict Lust in those years. Among other factors, for example, it is clear that Lust was deeply impressed by Adolf Just and his new book, Return to Nature. Changes in his own publications soon reflected the influences of Adolf Just. Lust may have encountered this German book, first published in 1896, while he was still in Germany during his healing treatments with Father Sebastian Kneipp. However, what is more likely, Lust found a German copy of the book in America. At the turn of the century, German migration to America was very significant. These immigrants brought with them their language, their food, their customs, their arts, and their predisposition to nature-cure.

The literature of the period shows that Lust’s path crossed with Just’s book. We can see the evidence in the trails left in The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly and The Naturopath and Herald of Health. Like many others who embraced Return to Nature philosophies, Lust was smitten. From 1900, Lust published translations of large tracts from Adolf’s book and advertisements of the book, Return to Nature, appear in practically every issue of Lust’s journal. Exposure to Just demonstrably planted seeds for Lust’s vision of creating a new system of health in America.

Adolf Just and Benedict Lust had more in common than similar sounding names. Like Lust, Adolf Just had also been afflicted with a very serious ailment landing him at death’s door. “All remedies, including those of the nature cure, proved unavailing, or at best gave only slight relief.” (Just, 1903, 1-2) Unable to find the help that he searched for, and distressed and tormented by his disease, Just decided to hand his fate to nature. His keen observation of nature and of the animals within nature helped guide his healing. Just states, “The creatures of pure nature, … the animals of our forests, are free from sickness and from everything else as well that corresponds to the sins and vices of mankind.” (Just, 1903, 4) Just concluded that people like animals in nature, could recover from illness if they would “heed again the voice of nature, and thus choose the food that nature has laid before him from the beginning, and to bring himself again into the relation with water, light and air, earth, etc., that nature originally designed for him/her.” (Just, 1903, 5)

Just came to “the conclusion that all healing is done by nature and that science can only assist nature.” (Lust, 1900, 127) Adolf Just designed a model for health and nature cure teachings in a setting that he used as a health retreat. Just called his sanitarium the ‘Jungborn’ or the ‘Well of Youth’ and based his teachings on the Return to Nature. Just located his first Jungborn in Eckerthal in the Harz Mountains in Germany to be “a model institution for the true natural life, where those who wish to make arrangements for such a life at home in their own gardens can find the pattern.” (Just, 1901, 264) Just used within his treatments, air, sun, water and earth as his healing tools.” (Lust, 1900, 127)

What exactly does Just mean when he says, “Return to Nature”? Lust explains, “Return to a natural diet, allow water, light and air to influence your system and all ailments will disappear, as well as all misfortune and discontent.” (Lust, 1900, 129) Benedict and Louisa Lust followed Just faithfully as they created the Yungborn in Butler, N.J. Lust incorporated the Kneipp water applications, air and light baths, as well as hardening practices such as barefoot walking and a natural diet. Louisa contributed greatly in the kitchen with her expertise in dietetics. To strengthen the natural healing power, various means were used that included, “outdoor life, sun and air baths, diet, water treatment, systematic exercises, massage, rest cure.” (Lust, 1913, 497)

The activities conducted at the Yungborn were just one part of the healing experience. It was recognized that the larger environment also needed to be conducive to healing. Carl Strueh describes the plight of the patients so embroiled in the struggles of living, “We are all slaves to unfavorable conditions or to foolish habits. The great majority of us sacrifice the largest part of our lives and our health in the fight for mere physical existence.” (Strueh, 1908, 125) Strueh and others recognized that vacations and rest cure were essential to counter the stresses and hardships of work and especially over-working. Strueh continues, “The more unfavorable the conditions under which we live and work, the more important it is that we should have a temporary interruption and change of habits. A few weeks’ vacation is the wisest investment for anybody who has voluntarily … overtaxed his bodily or mental capacity.” (Strueh, 1908, 126) Lust explains, “The state of a patient’s mind is of great importance in the treatment of disease. There is no greater obstacle to the progress of recovery than worry and no more powerful aid than a cheerful disposition.” (Lust, 1913, 496) The Yungborn facilities were made as comfortable and pleasant as possible to inspire health.

Light and Air

Just explains that humans are the “highest light- and air-creature. … Man can use the water for his benefit only at times in a certain form, while he cannot dispense with light and air for one moment without the greatest injury.” (Just, 1910, 712) Just considered air very important in the pursuit of health. “Man must in all diseases, acute and chronic, breathe always as much fresh air as possible, especially the air of the forest.” (Just, 1910, 712) Not only was the air vital for breathing but also the body equally needed to be exposed to air. Nudity was naturally condoned by Just and his followers.

The natural elements of sunshine, fresh air and living close to the land were key to the Jungborn experience. The view that sunlight was as essential to humans as it was to living plants made sunlight, “the most powerful force in Nature.” (Lust, 1913, 497) Wilhelmina Logan writes, “The sun is a glorious giver of life; we need it shining in our houses, cleansing and purifying the atmosphere.” (Logan, 1906, 266) The predominance of rainy, grey days in Portland, Oregon then, as now, may have inspired her next statement: “We cannot over-estimate the benefit which we derive from the glorious rays of the sun, which give us light, warmth, cheerfulness of mind, buoyancy of spirit and vigor of body.” (Logan, 1906, 267)

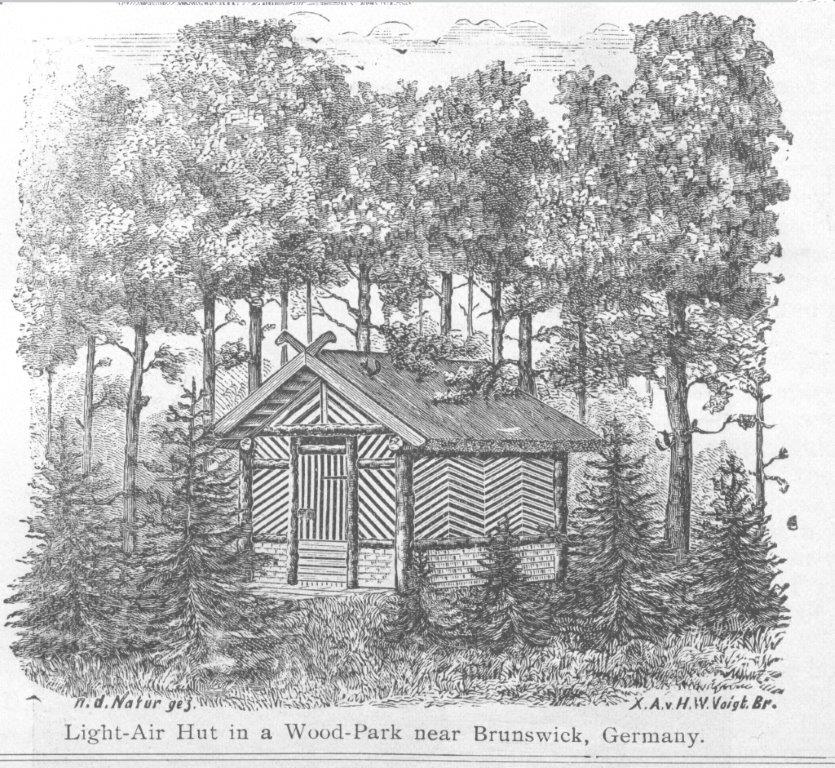

Today, we go camping in a state or provincial parks, but a century ago, tents would be replaced with “air houses” and people would find them at the Sanitariums or Yungborns of the day. Otto Carqué, who wrote on dietetics and nature, explains,

“To live in the open, in the sunshine, in the fields and woods, drinking pure air into the lungs, living on the simple products of garden and orchard, keeping a high attitude of mind, constantly directed towards the welfare of this fellow-men, is indeed man’s ideal life which will inaugurate in the evolution of mankind, characterized by the reign of human intellect, supreme harmony, and universal peace.”

Carqué, 1905, 157)

Like the modern Breitenbush hot springs located in Logan’s beloved Oregon, clothing was optional during the day in the private parks designated specifically for men and those specifically for women. “Separate sections of the sixty acres are set apart for the sexes, where the greatest freedom from dress restrictions may be enjoyed.” (Shaw, 1911, 147) “Each park is within a pine boarded stockade ten feet high, and no casual visitor is allowed with the sacred precincts.” (Lust, 1906, 118) Lust continues, “It is in these parks that all clothing is discarded and the open air, the natural and the earth baths are taken.” (Lust, 1906, 118)

Air Houses

At the Yungborn, people spent “more hours under the canopy of heaven than under the roofs made by man.” (Lust, 1906, 117) He adds, “There are wall and wedge tents, for single individuals or for families; there are primitive c abins and portable houses scattered about among the trees on the ledge of the hill giving the occupants a fine view of the Ramapo valley.” (Lust, 1906, 117) Lust describes the living arrangements made at the Yungborn, in Butler,

abins and portable houses scattered about among the trees on the ledge of the hill giving the occupants a fine view of the Ramapo valley.” (Lust, 1906, 117) Lust describes the living arrangements made at the Yungborn, in Butler,

“The guests under treatment live in charming little light and air cottages, surrounded by pines and other trees, and situated in large beautiful parks, which are surrounded by high natural walls of trees, vines, shrubberies, hills and mountains, so that everyone can at any time go directly from his room (and bed, at night or day, in the rain, etc.,) to take a light-and-air bath, a sun bath, a natural baths in the brook, etc.”

(Lust, 1913, Ad)

Those who preferred to sleep directly on the ground would be encouraged to. Just highly endorsed the “earth cure” and having direct contact with the ground during sleep.

The Earthen Power

Just saw men merely as highly evolved “moving plants” still needing to draw strength from the earth. (Just, 1910, 713) He observed that animals in the wild following instinct would “remove all the leaves and branches when lying down to be in immediate connection the earth in their repose.” (Just, 1910, 713) Just recognized that there was an electrical current inherent in the earth and “this electrical connection is much more complete when the entire body is in direct contact with the earth.” (Young, 1904, 69) At the Yungborn in Butler, such contact was encouraged especially at night.

Sleeping outside directly on the ground was optional, but many preferred it. By choosing the ground, he “who pitches his bed entirely under the open sky where his eyes are turned to the stars in fair weather and gentle zephyr breezes …[is rendered] conscious of all those eternal and mysterious powers of the grand nature which is so eager to cure the unhappy man.” (Just, 1910, 713)

Dr. C. W. Young, an Osteopath who was endeared to the Just earthen cure comments, writes in this regard,

“It is indeed a fact that the effect which the forces of the earth have upon man during the night is quite incredible. Whoever has not himself tried it and convinced himself of it can have no conception of how refreshing, vitalizing and strengthening the effect of the earth is on the human organism at night during rest.”

(Young, 1904, 69)

People would sleep naked directly upon the ground with a feather duvet covering them. Those who slept on the ground spoke exultingly of their experiences. The clinical reports made of the cures by sleeping on the ground attracted Young’s attention. “The cures effected were extraordinarily marvelous, and I noticed that the most emphasized agent of cure was the earth power.” (Young, 1904, 69) Having the courage to try it himself, Young stripped naked in October in Minnesota with frost on the ground, covered himself with a comforter, and woke up the next day with “new manifestation of vital energy so vividly described in Just’s wonderful book. I caught no cold whatever.” (Young, 1904, 69)

Young emphasized that one of the benefits of sleeping directly on the ground was strengthening the digestion. “Nothing accomplishes this end better than lying on the ground during the night.” (Young, 1904, 69)

The Food

Meal-time brought everyone together at the Butler Yungborn. Food was served in a big bungalow that was 80 feet long. The diet served at the Yungborn was principally vegetarian; however, individualized diets were available. Abundant fruits were served at Yungborn that were grown in the Yungborn orchards and, as Lust reports, also included “a bountiful supply of imported foreign fruit, such as oranges, figs, dates, mangoes, bananas, etc.” (Lust, 1907, 140) There were various kinds of nuts which were considered essential to the human diet. A raw vegetarian diet was available, as well as, “the richest milk, cream and butter, cottage cheese, buttermilk and fresh eggs, all home products, are served daily, as well as fresh vegetables in season.” (Lust, 1907, 140) Breakfast was served at 7 am and consisted of simple fare including “bread, fruit and water.” (Lust, 1908, 118)

Lust returned to Europe in 1908 to visit and revisit some of the most prestigious and outstanding sanatoriums of the times. He was welcomed with open arms by those who succeeded Father Kneipp after his passing in 1897. Dr. Baumgarten was one such successor of Father Kneipp whose work now was to represent the Kneipp method to the scientific world. (Lust, 1908, 119)

The one visit that left an indelible mark was Just’s Jungborn. Lust comments, “I have learned more and taken away more encouragement from this place than from any other and since I think as we Americans usually want the best there is, we should take [Adolf Just] as our model and pattern our institutions after his.” (Lust, 1908, 123) Lust’s visit to Just’s Jungborn galvanized Lust’s philosophies and principles into the Naturopathic movement forever. It is not surprising, then, to see that Lust published every month in his various journals, ads about Just’s book, Return to Nature.

Today, our large cities bursting at the seams and swallowing up land in every direction, choking on billows of polluted air, remind us that nature deprivation is a modern affliction too. Books such as Earthing by Ober, Sinatra and Zucker, with the primary goal of re-connecting with the earth and its wisdom has carved a large audience for those desperately wanting to feel connected to the earth again. Earthing lies in the Just earth-cure tradition in our time.

Carl Strueh established his sanatorium 30 minutes outside of Chicago at McHenry, Illinois. He offered similar services at his sanatorium giving Chicagoans a dose of Nature when tired and worn out. As Strueh comments, “The conditions we are living under do not allow us to do as nature intended us to. We are all slaves to unfavorable conditions or to foolish habits.” (Strueh, 1908, 125) Strueh encouraged us to “Go back to nature and live the simple life, as you were meant to.” (Strueh, 1908, 126) What our forebears faced, we face. What they have taught us to do about this assault on nature and our need for nature is absolutely relevant and timely.

Postscript: The Yungborn property in Butler, N.J. is now over-run by urban landscapes. State Highway #23 cuts the 60 acre into half and the beautiful resort buildings are all gone, replaced by a car sales lot. A link to an article online reveals a horrific demise to the once beautiful and serene Yungborn in Butler, New Jersey. http://www.vacantnewjersey.com/blog/entry/yungborn_health_resort_tunnel/index.html

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE incorporating ‘nature-cure’ approaches to primary care by including Balneotherapy, Breathing therapy and Nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a Faculty Member working as the Rare Books Curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a twelve volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in Balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for Naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE incorporating ‘nature-cure’ approaches to primary care by including Balneotherapy, Breathing therapy and Nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a Faculty Member working as the Rare Books Curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a twelve volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in Balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for Naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References

- Boyd, AL (1999). Yungborn, the life and times of Dr. Benedict Lust. This is a memoirs of Benedict Lust self published by his great niece, Anita Lust Boyd.

- Carqué, O. (1905). Nutrition in relation to health and disease. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VI(6), 151-157.

- Editorial Staff, (1901). Wedding bells. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II(6), 163.

- Just, A. (1901). Return to nature. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II(10), 264-267k.

- Just, A. (1903). Return to Nature. B. Lust Publishing, New York. Benedict Lust translated Adolf Just’s 4th enlarged German edition.

- Just, A. (1910). The new paradise of health. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XV(12), 711-721.

- Logan WG (1906). What the sunshine does for us. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VII(6), 266-267.

- Lust, B. (1900). Bellevue Sanatorium ad. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I(1), 16.

- Lust, B. (1900). Natural healing in America. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I(5), 79.

- Lust, B. (1900). Just and his methods. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I(8), 127-131.

- Lust, B. (1906). An Adam and Eve community within forty miles of New York. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VII(3), 117-120.

- Lust, B. (1907). The spring cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VIII(5), 139-140.

- Lust, B. (1908). The editor in Europe. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX(4), 116-124.

- Lust, B. (1913). Benedict Lust’s health resorts, “Yungborn”, Butler, N.J., and “Qui-si-sana,” Tangerine, Florida, The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVIII(7), 496-501.

- Lust, B. (1913). The Yungborn, Butler, N.J. and Tangerine, Florida, The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVIII(11), advertisement.

- Shaw, J.A. (1911). J. Austin Shaw explains Yungborn nature cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVI(3), 145-155.

- Strueh, C. (1908). The need of a vacation. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX(4), 125-127.

- Young, C.W. (1904). Osteopathic physical culture. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V(3), 66-69.